Gluteal Considerations for Patellofemoral Pain: Difference between revisions

m (references) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

== Conclusion == | == Conclusion == | ||

== | ==Resources== | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Revision as of 23:22, 3 June 2022

Original Editor - User Name

Top Contributors - Jacquie Kieck, Wanda van Niekerk, Jess Bell, Kim Jackson and Tarina van der Stockt

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Patella malalignment is influenced not only by the patella, but also by the position of the femur and trochlear. The position of the femur and trochlear is altered by the gluteal muscles, hence the need to assess, the gluteal muscles when considering patellofemoral pain[1][2]. The clinician should be cognisant that the assessment of the gluteal muscles in patellofemoral pain is not performed in isolation. Patellofemoral pain should be assessed holistically, considering various factors, including local factors around the knee, whole limb assessment and psychosocial factors[3] such as fear of movement and pain catastrophisation[4].

Why Do We Need to Consider Each Muscle?[edit | edit source]

An understanding of the gluteal muscle's function in each plane of movement is imperative for accurately assessing the performance of the gluteal muscles. When the clinician can specifically identify the plane of movement in which the dysfunction occurs, as well as isolate the offending structure, targeted rehabilitation exercises can be prescribed.

Functional Role of the Gluteal Muscles[edit | edit source]

Gluteus Medius as an Abductor in the Frontal Plane[edit | edit source]

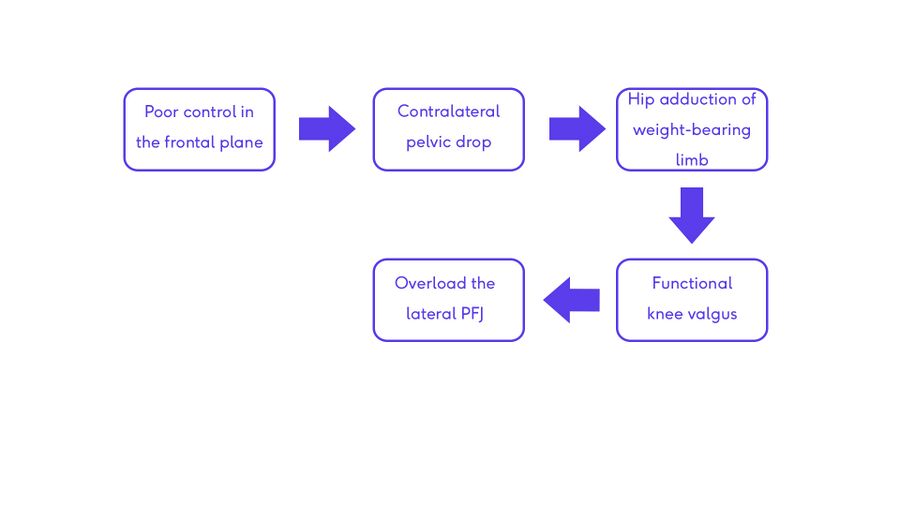

Gluteus medius acts as an abductor of the hip in the frontal plane. Poor hip abduction control in a single-stance, weight-bearing position allows for contralateral pelvis drop. In this scenario, the weight-bearing limb essential falls into adduction, causing a functional valgus at the knee. This in turn creates greater load on the lateral patellofemoral joint (PFJ)[5].

Gluteus medius is assessed in the frontal plane by performing hip abduction. A recommendation is to perform the test by maintaining the resistance against hip abduction for 10 seconds. By sustaining the resistance to the muscle, it ensures that the tonic performance of the muscle is assessed (and not the phasic performance of the muscle which would be what is assessed in the first couple of seconds of holding the position against resistance). This is important because gluteus medius should act as a postural endurance muscle to stabilise the pelvis[6].

Assessment of the gluteus medius can also be performed in a weight-bearing position assessing the ability of the person to control the pelvis as they perform a contralateral hip drop when standing on a step. This position allows for concentric and eccentric assessment of the gluteus medius function. This position is also effective for strengthening of the gluteus medius[7].

Gluteus Medius as an External Rotator in the Horizontal Plane[edit | edit source]

The posterior fibres of gluteus medius are active as the primary external rotator of the hip at 0º to 20º of hip flexion. From 20º to 50º of hip flexion, the posterior fibres of gluteus medius are still active. Above 50º hip flexion the gluteus maximus is the primary external rotator. Hence to test the gluteus medius resistance must be given against hip external rotation when the hip is in )0º to 20º of flexion.

| Hip Flexion | 0º - 20º | 20º - 50º | >50º |

| Primary external rotator of the hip | Gluteus Medius | Gluteus Medius is still active | Gluteus Maximus |

Gluteus Maximus[edit | edit source]

Gluteus maximus externally rotates the hip when the hip is flexed. Testing of the gluteus maximus should be performed by providing resistance against external rotation of the hip when the hip is flexed. It is recommended to sustain the hold against external rotation, in this position, for ten seconds to test the tonic action of the muscle.

Rehabilitation Exercises[edit | edit source]

Gluteus Medius in the Frontal Plane (Hip Abduction)[edit | edit source]

Gluteus Medius in the Horizontal Plane (Hip Lateral Rotation at <20º of Hip Flexion)[edit | edit source]

Gluteus Maximus in the Horizontal Plane (Hip Lateral Rotation at >50º of Hip Flexion)[edit | edit source]

Functional Role with Different Activities[edit | edit source]

Gait[edit | edit source]

During gait gluteus maximus works eccentrically to control rotation[8]. After heel strike, about 24% into weight bearing, the femur and the tibia will internally rotate. This is normal, but needs to be for a short period only. Excessive internal rotation of the femur creates maltracking of the patella, loading the lateral patellafemoral joint. To correct this we need to create an awareness for the patient of this, and then strengthen the eccentric control of the gluteus maximus.

Running[edit | edit source]

Increased running speed is associated with increased movement in the frontal plane of contralateral hip drop and corresponding hip adduction.

Landing From a Jump[edit | edit source]

Jump landing kinematics are affected by lower limb injuries, including patellofemoral pain[9]. Psychosocial considerations such as kinesiophobia can be a consideration with landing from a jump. The clinician must assess if the poor jump landing is due to poor gluteal control, or are there other factors contributing to this.

Muscle Inhibition[edit | edit source]

A history of low back pain[10] [11]or ankle injuries[12] are relevant to gluteal function. Low back pain has been shown to inhibit gluteus maximus, and ankle inversion injuries are related to gluteus medius inhibition.

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Ireland ML, Willson JD, Ballantyne BT, Davis IM. Hip strength in females with and without patellofemoral pain. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2003 Nov;33(11):671-6

- ↑ Sadler S, Cassidy S, Peterson B, Spink M, Chuter V. Gluteus medius muscle function in people with and without low back pain: a systematic review. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2019 Dec;20(1):1-7

- ↑ Crossley KM, van Middelkoop M, Barton CJ, Culvenor AG. Rethinking patellofemoral pain: prevention, management and long-term consequences. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2019 Feb 1;33(1):48-65.

- ↑ Uritani D, Kasza J, Campbell PK, Metcalf B, Egerton T. The association between psychological characteristics and physical activity levels in people with knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2020 Dec;21(1):1-7

- ↑ Lee TQ, Anzel SH, Bennett KA, Pang D, Kim WC. The influence of fixed rotational deformities of the femur on the patellofemoral contact pressures in human cadaver knees. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1994 May 1(302):69-74

- ↑ de Souza LA, Curtarelli MB, Dionisio VC. Overflow of Muscle Activation by Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation in Standing Position: A Cross-Sectional Electromyographic Investigation in Healthy Individuals.

- ↑ Moore D, Semciw AI, Pizzari T. A systematic review and meta-analysis of common therapeutic exercises that generate highest muscle activity in the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus segments. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2020 Dec;15(6):856.

- ↑ Preece SJ, Graham-Smith P, Nester CJ, Howard D, Hermens H, Herrington L, Bowker P. The influence of gluteus maximus on transverse plane tibial rotation. Gait & posture. 2008 May 1;27(4):616-21.

- ↑ De Bleecker C, Vermeulen S, De Blaiser C, Willems T, De Ridder R, Roosen P. Relationship between jump-landing kinematics and lower extremity overuse injuries in physically active populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine. 2020 Aug;50(8):1515-32.

- ↑ Bullock-Saxton JE, Janda V, Bullock MI. Reflex activation of gluteal muscles in walking. An approach to restoration of muscle function for patients with low-back pain. Spine. 1993 May 1;18(6):704-8.

- ↑ Sadler S, Cassidy S, Peterson B, Spink M, Chuter V. Gluteus medius muscle function in people with and without low back pain: a systematic review. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2019 Dec;20(1):1-7.

- ↑ Beckman SM, Buchanan TS. Ankle inversion injury and hypermobility: effect on hip and ankle muscle electromyography onset latency. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1995 Dec 1;76(12):1138-43.