Gait Definitions

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Walking is an integral part of humans' daily locomotion and an important indicator of health. It is the most common physical activity that most adults will do in their leisure time.[1]

Human gait depends on a complex interplay of major parts of the nervous, musculoskeletal and cardiorespiratory systems.

- The individual gait pattern is influenced by age, personality, mood and sociocultural factors.

- The preferred walking speed in older adults is a sensitive marker of general health and survival.

- Safe walking requires intact cognition and executive control. It is a complex biomechanical process of dynamic balance which requires a person to maintain their centre of gravity within their base of support throughout movement.[2]

- Gait disorders lead to a loss of personal freedom, falls and injuries and result in a marked reduction in the quality of life[3].

Thus, it is valuable to be able to measure and analyse human gait. In order to do so, a number of relevant terms and parameters have been defined.

Gait Definitions[edit | edit source]

- Gait

- Upright locomotion in the particular manner of moving on foot which may be a walk, jog or run.

- Walking

- A particular form of gait and the most common of human locomotor patterns.

- Ambulation

- A broad sense as a type of locomotion and is more often used in the clinical sense of describing whether or not someone can walk freely or with the assistance of some device.

Gait Development[edit | edit source]

- Children take approximately 11 to 15 months to learn and develop gait[4]

- Refinement and normalisation of a gait pattern takes another 4 - 5 years

- Children around the ages of 6 - 7 years will have a normalised, adult-like gait pattern

- Gait changes throughout the lifespan[5]

Normal Gait or Ideal Gait?[edit | edit source]

An "ideal" gait needs to be both safe and energy efficient[7] For example[7]:

- The "ideal" gait of an individual with an orthopaedic injury and/or neurological condition may be considerably different from a clinician's picture of "ideal"

- As long as the individual is ambulating as safe as possible and in the most efficient manner possible, their "dysfunctional" gait pattern is actually their "ideal" gait pattern

- An assistive device or brace should not always be looked upon as a "crutch"

- If the device or brace improves an individual's safety, confidence, and/or unloads the injured structure then it is a positive addition to the gait pattern

Major Tasks of Gait[edit | edit source]

- To maintain support of the head, arms and trunk

- To maintain upright posture and balance of the body

- To control foot trajectory to achieve safe ground clearance and a gentle heel or toe landing

- To generate mechanical energy to maintain the present forward velocity or to increase the forward velocity

- To absorb mechanical energy for shock absorption and stability or to decrease the forward velocity of the body

Important Terminology of Gait[edit | edit source]

- Gait cycle

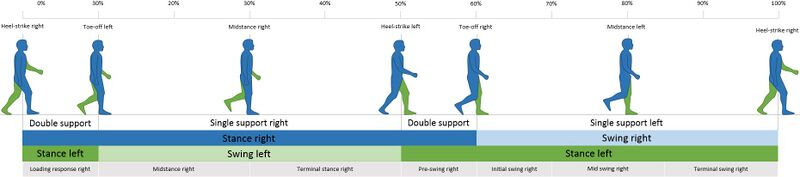

- A repetitive pattern involving steps and strides[8] or the time from when the heel of one foot touches the ground to the time the same heel touches the ground again. The gait cycle is divided into two phases which are further divided into eight sub-phases:

- Stance Phase (60% of the gait cycle) - during which some part of the foot is in contact with the ground:

- Initial contact/heel strike

- Foot flat

- Mid-stance

- Heel off

- Toe off

- Swing Phase (40% of the gait cycle) - during which the foot is not in contact with the ground:

- Initial swing

- Mid-swing

- Late swing

- Centre of Mass (COM)

- The point where the mass of the body is centered

- Usually 5 cm anterior to S2 in adults

- Centre of mass is not a fixed point and changes in different positions such as sitting, standing and kneeling

- Displacement of Centre of Mass

- It is difficult to follow and evaluate the movement around S2, therefor another way to assess the displacement of the centre of mass of a body is to observe the head for a vertical representation of the movement of the COM

- The lowest point will be at double leg stance

- Highest point will be at mid-stance/mid-swing

- Vertical change of COM will be about 5 cm

- Difficult to measure, but instead look for excessive amounts of vertical displacement

- Centre of Mass also shifts from side to side during ambulation

- Maximal shift to the right will occur during right mid-stance

- Maximal shift to the left will occur during left mid-stance

- Side to side shift of COM will be about 4 cm

- Difficult to measure, but instead observe to see if the individual ambulates with a wide or narrow base of support

- It is difficult to follow and evaluate the movement around S2, therefor another way to assess the displacement of the centre of mass of a body is to observe the head for a vertical representation of the movement of the COM

- Ground Reaction Force

- Forces applied by the ground to the foot, when the foot is in contact with the ground

- Generates External Torque

- External Torque

- Torque that acts upon the body

- When external torque passes at a distance from the axis - this causes rotation of the superimposed body segment around that joint axis

- The magnitude increases as the distance increases between the ground reaction force and the joint axis

- Internal Torque

- Muscle contractions to counterbalance external torque

- Ground reaction force anterior to joint axis

- Causes anterior motion of the proximal segment

- Flexion moment

- Ground reaction force posterior to joint axis

- Causes posterior motion of the proximal segment

- Extension moment

- External Torque

- Read more: Ground Reaction Forces

- Please view this video which provides a detailed overview of ground reaction forces during gait.

- Centre of Pressure

- Single point on the foot at which the surface pressure is acting

- This is the starting point of Ground Reaction Forces

- Barefoot pattern is different to shoe wearing pattern

- Pattern:

- Posterior-lateral edge of the heel (beginning of the stance phase)

- Moves in a linear pattern through the mid-foot area (lateral to the midline)

- Moves medially across the ball of the foot with a large concentration along the metatarsal break

- Centre of Pressure (CoP) moves to the second and first toes during late stance

Gait Observation[edit | edit source]

Observe an individual's standing posture before assessing their gait

Observe an individual's footwear before formally assessing their gait

Gait analysis - An analysis of each component of the two phases of ambulation is an essential part of the diagnosis of various neurological disorders and the assessment of patient progress during rehabilitation and recovery from the effects of neurologic disease, musculoskeletal injury or disease process, or amputation of a lower limb. Clinicians and researchers use various qualitative and quantitative parameters to analyse gait. A systematic review[10] in 2017 found that the most relevant parameters for gait analysis in a healthy adult population were walking velocity, cadence, and step/stride length. The authors defined relevant parameters as those that help clinicians identify gait abnormalities applicable in a rehabilitation setting.

Step length - The distance between the initial contact of one foot and the initial contact of the contralateral foot. Normal step length is on average about 70 cm.[11]

Stride length - The distance between the consecutive initial contacts of the same foot.

Step time - The time between the initial contact of one foot and the initial contact of the contralateral foot[8].

Stride time - The time between the consecutive initial contacts of the same foot.

Step width - The mediolateral space between the two feet[8]. Average normal step width is between 8-10 cm.[11]

Cadence - The number of steps taken per minute (steps/minute). Healthy adults average about 90-120 steps per minute for a comfortable walking speed.[11]

Gait speed/velocity - Velocity is determined by one's cadence and step length, measured in units of distance over time (metres/second). Clinically, it is often calculated by measuring the time it takes to walk a specified distance, usually 6 m or less. Healthy adults will self-select a comfortable walking speed of about 1.34 m/s on average[11]. Slower speeds correlate with an increased risk of mortality in geriatric patients.[12] Normal walking speed primarily involves the lower extremities, with the arms and trunk providing stability and balance. With faster speeds, the body depends on the upper extremities and trunk for propulsion, balance, and stability with the lower limb joints producing greater ranges of motion.[13]

The following video shows a 4-metre walk test:

The demarcation between walking and running occurs when periods of double support during the stance phase of the gait cycle (both feet are simultaneously in contact with the ground) give way to two periods of double float at the beginning and the end of the swing phase of gait (neither foot is touching the ground)[15].

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Schuna J, Tudor-Locke C. Step by Step: Accumulated Knowledge and Future Directions of Step-defined Ambulatory Activity. Res Exerc Epidemiol [Internet]. 2012;14(2):107–16. Available from: http://jaee.umin.jp/REE/J/14_2_107.pdf

- ↑ Beauchet O, Allali G, Sekhon H, Verghese J, Guilain S, Steinmetz J-P, et al. Guidelines for Assessment of Gait and Reference Values for Spatiotemporal Gait Parameters in Older Adults: The Biomathics and Canadian Gait Consortiums Initiative. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience [Internet]. 2017 Aug 3 [cited 2022 May 11];11. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00353/full

- ↑ Pirker W, Katzenschlager R. Gait disorders in adults and the elderly. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift. 2017 Feb 1;129(3-4):81-95.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5318488/ (last accessed 27.6.2020)

- ↑ Bonnefoy A, Armand S. Normal gait. Orthopedic management of children with cerebral palsy: A comprehensive approach. 2015:567.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Iosa M, Fusco A, Morone G, Paolucci S. Development and decline of upright gait stability. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2014 Feb 5;6:14.

- ↑ Mikolajczyk T, Ciobanu I, Badea DI, Iliescu A, Pizzamiglio S, Schauer T, Seel T, Seiciu PL, Turner DL, Berteanu M. Advanced technology for gait rehabilitation: An overview. Advances in Mechanical Engineering. 2018 Jul;10(7):1687814018783627.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Kopelovich, A. Gait Definitions and Gait Cycle. Course, Plus. 2022

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Loudon J, et al. The clinical orthopedic assessment guide. 2nd ed. Kansas: Human Kinetics, 2008. p.395-408.

- ↑ Alexandra Kopelovich. Ground Reaction Force During the Gait Cycle. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y2RHvicAM2o&t=62s[last accessed 24/08/2022]

- ↑ Mary Roberts. Biomechanical parameters for gait analysis: a systematic review of healthy human gait. Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation [Internet]. 2017 Aug 16 [cited 2022 May 11];4(1):6. Available from: https://www.hoajonline.com/phystherrehabil/2055-2386/4/6

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Webster JB, Darter BJ. Principles of Normal and Pathologic Gait. Atlas of Orthoses and Assistive Devices [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2022 May 11];49-62.e1. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780323483230000044

- ↑ Medical dictionary Gait speed Available from: https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/gait+speed (last accessed 28.6.2020)

- ↑ Shultz SJ et al. Examination of musculoskeletal injuries. 2nd ed, North Carolina: Human Kinetics, 2005. p55-60.

- ↑ NIH Toolbox. NIH Toolbox 4-Meter Walk Gait Speed Test Age 7+. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xLScK_NXUN0&ab_channel=NIHToolbox

- ↑ The biomechanics of running Tom F. Novacheck Motion Analysis Laboratory, Gillette Children’s Specialty Healthcare, Uni6ersity of Minnesota, 200 E. Uni6ersity A6e., St. Paul, MN 55101, USA Received 25 August 1997; accepted 22 September 1997 Available from: