Frail Elderly: The Physiotherapist's Role in Preventing Hospital Admission

Frailty[edit | edit source]

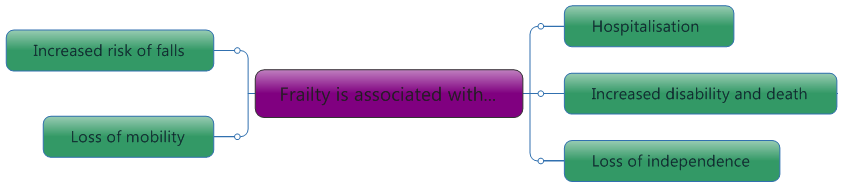

Frailty is a clinical state that is associated with an increased risk of falls, harm events, institutionalisation, care needs and disability/death.[1]The physiotherapist should be aware of the risk factors for frailty. If frailty is suspected, referral to other professionals may be required. Frailty and disability do not always co-exist, however they can be linked. In some cases, frailty may be a consequence of disability and in others, the causation of disability[2].

|

It is important to note that although frailty is age-related, it is not an inevitability[4]. In those aged 65 to 85, there is thought to be a 10% incidence of frailty. However, this figure increases to 25 to 50% in those aged 85 and over[5].

Ageing Population[edit | edit source]

People worldwide are living longer, with most people expected to live into their sixties and beyond. Every country in the world is experiencing growth in both the size and the proportion of older persons in the population. Older age may involve complex health states, commonly called geriatric syndromes, often the consequence of multiple underlying factors and include frailty, urinary incontinence, falls, delirium and pressure ulcers. So today with the growing older populations, healthcare services are required to transform to better meet the population’s needs[6][7].

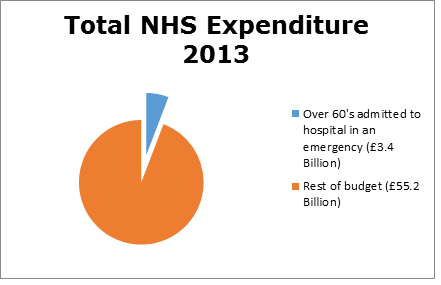

Costs[edit | edit source]

Health care costs already account for between 8% and 10% of GDP in developed countries. It is anticipated that even a modest increase in health care costs would generate significant pressure on the economy. For this reason every developed country is attempting to reform its health care system.[8]

The length of time frail people stay in hospital differs throughout the world. The UK is 16th shortest in the world when it comes to the average length of stay in hospital[9]. However, admittance to hospital and the cost implications of long term hospital stays are similar worldwide to the UK[10][11].

Relevance[edit | edit source]

The next decades we will be faced with an ageing population with more elderly dependants. This means that there will be more of a financial strain health care systems to the prolonged hospital stays associated with age.

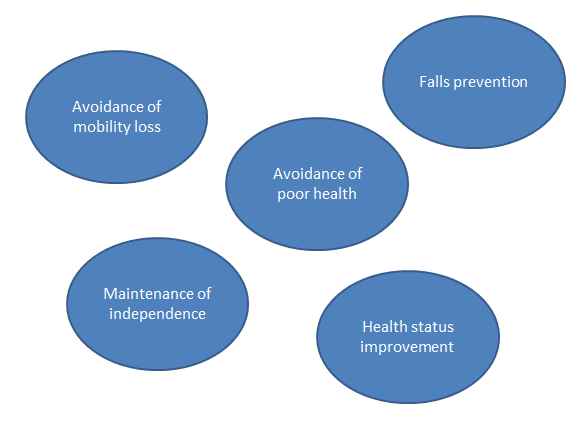

Preventative healthcare strategies include[12]

- Promoting healthy behaviours like physical activity

- Reducing tobacco and alcohol use

- Improving community facilities to promote physical activities.

- Raising awareness of frailty

Introduction to the Physiotherapist's Role[edit | edit source]

The nature of the physiotherapy profession is to help restore movement and function in someone affected by illness or injury[13]. However, as previously discussed, the delivery of care is evolving in order to better meet the needs of this population. Physiotherapist’s are expanding their service to deliver intervention out with standard inpatient care and moving to several different settings; for example, within day hospitals, in the patient’s home and in community clinics.

There is an emerging body of evidence supporting physiotherapy in emergency departments to assess and treat trauma and soft tissue injuries[14].

In 2015, a physiotherapist joined forces with paramedics to treat non-life-threatening emergency calls, with the aim of preventing unnecessary A&E attendances and reducing hospital admissions. Commonly seen conditions included falls, chronic pain, decreased mobility, exacerbations of long-term conditions and frailty. 57% of patients remained at home and it is thought that £2850 was saved every time a patient was not transferred to hospital[15].

Furthermore, it has been suggested that physiotherapists could be stationed within hospital A&E departments to undertake frailty and falls risk screening and make rapid decisions on whether the patient can safely return to their pre-admission destination[16][17]. However, little high quality research has been conducted and at present evidence is inconclusive, suggesting the need for further study in this area. A randomized control trial[18] suggests home-based exercise and nutrition strategies have a positive outcome on the frailty score and physical perform

propriate measure for their practice. Medical Management

Frail adults are highly likely to be prescribed medication to treat their symptoms and co-morbidities. Below you will find a list of common medications, the conditions they are used to treat, some common side effects and some named examples[19].

| Medication | Conditions used to treat | Common side effects | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non- opioid analgesics (Non-steroidal anti- inflammatory drugs, NSAIDs) |

Mild to moderate pain | Minimal side effects, however dizziness and headache may occur | paracetamol, aspirin, ibuprofen |

| Compound Analgesics | Mild to moderate pain, often as an addition to NSAIDs | Nausea, loss of concentration, constipation, confusion | co-codamol, co-codaprin, co-dydramol |

| Opioid analgesics | Moderate to severe pain. | Impaired balance, confusion nausea and vomiting, constipation, drowsiness and dizziness | codeine, tramadol morphine |

| Medication | Conditions used to treat | Common side effects | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta Blockers[20] | Angina, Heart failure, Atrial fibrillation and Heart attach | Dizziness, tiredness, blurred vision, slow heartbeat, impaired balance | atenolol, bisoprolol, acebutolol, metoprolol |

| Antidepressants[21] | Depression | Dizziness, impaired balance, slow reaction, headaches, loss of appetite, anxious, feeling agitated, blurry vision |

duloxetine, venlafaxine, mirtazapine, amitriptyline, imipramine, lithium. |

| Benzodiazepines[22] | Relief of severe anxiety | Drowsiness, difficulty concentrating, headaches and vertigo | diazepam, lorazepam, chlordiazepoxide |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers[23] | Hypertension | Dizziness, confusion, muscle cramps and/or weakness, faintness | azilsartan, candesertan, eprosartan, losartan |

|

Diuretics[24] |

Water retention, high blood pressure and heart failure |

Nausea, dizziness, muscle cramps, increased frequency and urgency of urination |

furosemide, torsemide, chlorthalidone, amiloride |

| Anticoagulants[25] | Hypotension | Haemorrhage, dizziness, headaches. | heparin, warfarin and aspirin, |

Side effects of medication such as drowsiness, blurred vision and insomnia can interfere with the treatment session and also delay any recovery. It is therefore important for physiotherapists to know if the patient is on any medication and the associated side effects so they can modify treatments.

Polypharmacy is the use of multiple medications and is often unavoidable as the elderly population are more likely to have several co-morbidities. Polypharmacy introduces drug interaction, this can be harmful as when combined, some medications increase the risk of adverse drug reactions (ADRs)[26].

ADRs can become a vicious cycle where more drugs are prescribed in order to treat side effects. This can result in increased numbers of unnecessary and potentially harmful medications. The physiotherapist can help prevent polypharmacy and the vicious cycle by recognising changes in the patient's response to their drug therapy and highlighting need for medication review[27]. It is fundamental for physiotherapists to have knowledge and understanding of common medicine and their adverse side effects.

Nutritional Status[edit | edit source]

Nutrition is important for this population and it should be part of the physiotherapist's subjective assessment to check dietary intake[28]. A physiotherapist can then reinforce good eating habits and if needed, refer the patient to a dietician. It is also important to have an idea about how much the patient eats as this could contribute to increased fatigue. A reduced tolerance to activity is present in frail patients[29] and the physiotherapist should be mindful of this when assessing and treating.

Mental Health[edit | edit source]

Although it is not the prime role of a physiotherapist, in order to provide a holistic service, we must be aware of and understand the mental health of our patients and the impact that this may have on the individual. Mental health disorders can be classified as organic or functional[30]

Organic[edit | edit source]

Age-related cognitive decline is inevitable[31], however, some conditions common amongst frail adults can have dramatic effects on cognition[32]. Organic disorders are usually caused by disease affecting the brain, for example, dementia or delirium. Depression and anxiety can also be seen in these frail adults.

Implications for Physiotherapists[edit | edit source]

With any cognitive condition, effective communication may become challenging and prove to be a barrier to successful assessment and treatment. Some tips to tackle this are:

- Keep commands clear and concise with one request at a time – “Stand up please”

- Allow plenty of time for a response before repeating your question. If the patient is still struggling, try rephrasing.

- Remove distractions – this could include talking, background noise, eye-catching pictures.

- Use names and explanations where possible – “Your daughter, Ann”

- Use other forms of communication:

- Visual – show tasks rather than explaining instructions.

- Sound – cueing can encourage normal movement. For example, counting or using music can provide a rhythm and trigger a response. It may also help provide an auditory clue when the patient cannot understand the verbal instruction – patting the chair to signify “sit down”.

- Tactile – can be used to aid the movement. For example, offering a hand when walking, stroking up the spine when standing.

Lack of motivation is common amongst most frail adults, including those with a functional mental health disorder and treatment to tackle this can feature heavily in the physiotherapy treatment plan[33].

Social and Environmental Factors[edit | edit source]

Assessing this type of information is also a key component of the common assessment framework for adults, which was published by the Department of Health[34]. It is primarily an occupational therapists (OT’s) role to devise interventions and amend any problems with these. Their assessment and the subsequent home modifications and adaptions can help increase the functional abilities of people who are frail[35]. However, a patient's ability to carry out activities in the home is dependent on its layout and their social situation. As physiotherapy interventions try to help improve people's ability to perform ADLs, it is important for physiotherapists to know how the environment and social situation can impact on their treatment. The international classification of health, functioning and disability (ICF)[36] can be used by physiotherapists to help establish the needs of the patient.

Social Circumstances[edit | edit source]

Activity Limitations[edit | edit source]

Frail people who have a high participation level in leisure activities also have better health outcomes. Reduced mobility and activity limitations directly reduce participation in leisure activities. Activity limitations can have a bigger impact on social involvement than the severity of the patient's medical condition. Specific activity limitations which may cause participation restriction are:

- Anxiety[37][38]

- Needing help with personal care[39][38]

- Mobility aid use and walking speed[38][39][40]

- Memory[40][39]

Musculoskeletal impairments cause the majority of activity limitations in elderly community-dwelling adults[41] . Physiotherapists are therefore in a prime position to help reduce activity limitations. A study by Mast and Azar[42] found a correlation between ADL limitations and readmission to hospital in the geriatric population. This shows that physiotherapy targeted at reducing activity limitations could reduce hospital stay as well as improving social network and participation.

Taking a Social History[edit | edit source]

Taking a social history allows the physiotherapist to understand the patient's current level of functioning and their desired functional goals[43][44]. This should include assessment of activities they do in and outside their home and what formal or informal care or support they receive[45][43]. 80% of nonagenarians have carers to help with some of their ADLs[39]. Having a small amount of regular help with ADL’s may prevent an acute episode turning into an emergency, where the patient is no longer safe to stay at home[45]. This shows the importance of knowing the patient's social circumstances.

Environment [edit | edit source]

Participation Restrictions[edit | edit source]

Elderly people who experience activity limitations sometimes also have participation restrictions[46][39][47]. Knowing what participation restrictions a patient has is important as they are linked to the patient's quality of life. Participation frequency should also be noted[46]. It is common for people with frailty who live in the community to report having participation restrictions[48][49]. This is due to reduced community mobility and a reduced ability to carry out work both at home and in the community[48]. Increased participation restrictions are also linked with increasing age[50]. The symptoms of frailty most closely linked to participation restrictions are grip strength, mobility and the number of co-morbidities a patient has[48]. Participation is also linked to environmental factors such as, access to public transport. It has been shown that mobility levels can remain constant even though the patient's condition may decline[51]. The mind map below shows the different things which should be checked in the patients' house on assessment, before a treatment plan is devised or goals are set. Sometimes these assessments are performed jointly with an OT[45]. It is important to know if any intervention is being put in place to help rectify these. Finding out if an OT is involved, what their findings were and what their plan is, is important as then interdisciplinary goals can be devised, which are safe and suited to the patient[52] Being aware of the environment in which the patient lives will allow the physiotherapist to tailor treatments effectively and safely to their surroundings.

Physiotherapy Treatment[edit | edit source]

There are several clinical guidelines available for healthcare professionals to assist them in preventing hospital admissions providing quality care for patients. However, whilst they recommend physiotherapy intervention, these guidelines lack rigorous information and evidence surrounding treatment. As two thirds of NHS clients are aged 65 or over[53], there is a plethora of different occasions in which an older person may be admitted to hospital, however, it can be loosely split into two categories: injury and illness [54].

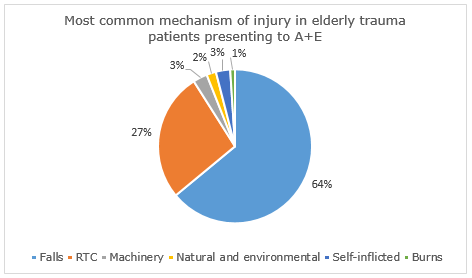

Injuries leading to hospitalisation are more common in people over 65 and they can be more critical and more often preventable. The increasing age of the population heightens the significance of this problem[55]. Falls represent the most frequent and serious type of accident in people aged 65 and over in the UK [56]. Gowing and Jain[57] found that a fall is the most common mechanism of injury in elderly trauma patients presenting to accident and emergency units and falls cases are the most common presentation to the Scottish Ambulance Service in the older adult population[58].

|

|---|

The natural ageing process means that older people are at higher risk of falls. Over 400 risk factors leading to falls have been highlighted (Table 9).

A multifaceted interaction of several risk factors relating to the ageing process, lifestyle choices, environmental factors and the presence of long term conditions determines an individual’s risk of falling[56]. As risk increases with age, it is important for the physiotherapist to identify those at risk early, recognise and modify risk factors and provide timely intervention to prevent falls and subsequent injury[59].

[edit | edit source]

Below are examples of treatment options follows, although this list is not exhaustive.

Resistance Training[edit | edit source]

A significant component of age-related weakness and frailty is sarcopenia. Sarcopenia increases the risk of frailty and falls and in turn, hospitalization in the older adult population[60]. Resistance training has been suggested as a potential treatment for sarcopenia and its prevention. Resistance training is designed to improve muscular fitness by exercising a muscle or a muscle group against resistance[61]. This could lead to improved function, increased quality of life and reduced likelihood for falls[62]. Resistance training programmes have consistently shown to improve muscle strength and mass in older adults[63][64], however, it is questionable whether this transfers to reducing the risk of falling.

Latham and colleagues[65] have conducted the only trial which has studied the effect of seated resistance training on risk of falls in an older adult population. It was found to have no effect on falls rate or risk of falling and an increased chance of musculoskeletal injury. As a result, seated resistance training or high intensity resistance are not recommended. Furthermore, Liu-Ambrose and colleagues[66] examined the effect of a twice weekly course of 50-minute resistance training sessions on number of falls and risk of falls in a female population aged 75-85. Exercises included targeted upper limb, trunk and lower limb muscles and again, resistance training alone was found to have no significant effect on number of falls or risk of falls. However, when combined with agility training, participants did develop a decreased risk of falling. It has been proposed that strength training alone is not enough to fully manage falls risk, however, it should be part of a multi-component falls prevention exercise programme[67]. We will discuss this in further detail later on in the learning resource.

Balance Re-education[edit | edit source]

Balance disorders are very common in frail older adults and are a key cause of falls in this population. They are associated with reduced level of function, as well as an increased risk of disease and death. Most balance disorders comprise of several contributing factors including long-term conditions and medication side effects[68]. Recent research conducted examined the effectiveness of two-year progressive balance retraining in reducing injurious falls among community-dwelling women aged 75-85[69]. The study took place over 20 centres and recruited 706 participants, who were randomised in to the intervention group, who received weekly dynamic balance exercise supplemented by prescribed home exercise, or the control group, who did not take part in the exercise. Over the two-year intervention period, the injurious fall rate was 19% lower in the intervention group than in the control group highlighting the benefit of a balance training programme.

Exergaming is a relatively new treatment concept and is thought to increase motivation and enjoyment for users.

The Nintendo Wii has a built in pressure sensor that allows for feedback to be delivered to the user on their performance. There is evidence that a Wii based balance exercise programme could improve balance ability in the frail elderly population[70], so as a result, Fu and colleagues[71] conducted research into whether this would transfer to reducing fall risk and incidence.

Sixty participants aged 65 or over received balance training three times per week for six weeks. They were randomly allocated into the intervention group who undertook balance activity on the Wii, or the control group who received conventional exercise. The results showed that while both groups reduced their risk and incidence of falls, the intervention group showed a more significant improvement.

The Wii balance training has shown to reduce falls by 69% compared with conventional training. Additionally, the intervention group had a 35% improvement in the fall risk score, considerably greater than that of the conventional balance training at 11%. As a result, the use of the Nintendo Wii for balance re-education is highly recommended and perhaps this suggests the need for further research on various other computer games available.

Tai Chi[edit | edit source]

Tai chi is a newly emerging exercise incorporating breathing, relaxation and slow and gentle movements with strengthening and balance exercises. Whilst originally an ancient 13th century Chinese martial art, it has recently become more prevalent around the world as a health-promoting exercise[72]. Whilst there is room for more rigorous research on the health benefits of tai chi, it is thought that it could help adults aged 65 and over in improving balance[73], reducing stress[74] and controlling osteoarthritis pain[75]. Additionally, in a high quality systematic review, tai chi was not only found to significantly reduce rate of falls, but also lessen risk of falls[76]. As tai chi is considered a low impact exercise, it is suitable for most to participate in and should be considered as a treatment option.

Otago Exercise Programme[edit | edit source]

The Otago Exercise Programme (OEP) is an evidenced-based, "home-based, individually tailored strength and balance retraining programme”[77]. The OEP is carried out by physiotherapists (and/or trained providers such as community nurses). It is designed to be carried out over 12 months (or more recently, six months). The physiotherapist makes approximately five home visits within that period and also makes monthly phone calls to the participant to encourage adherence[78].

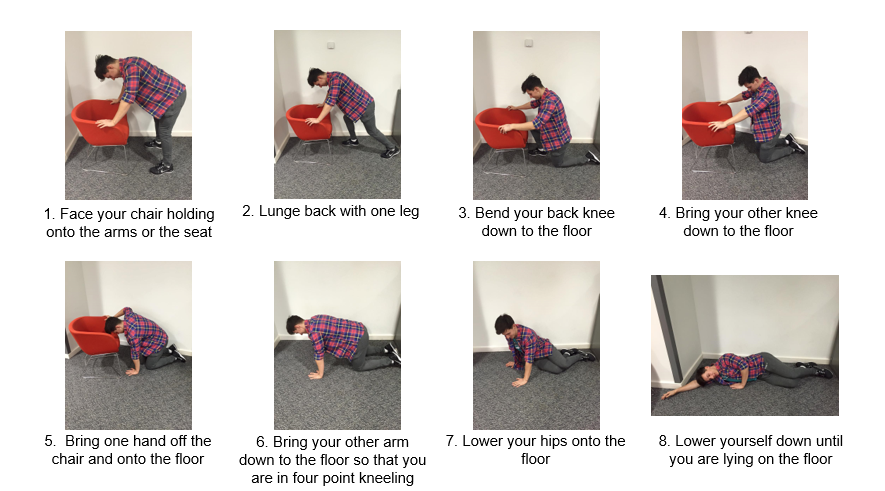

Backward-chaining[edit | edit source]

Declining muscle function in older adults reduces their ability to rise from the floor following a fall and up to a half of all non-injured fallers are unable to get up[79]. When someone is unable to get up off the floor unassisted, the associated risks are far greater due to the complications that can occur from lying on the floor for an extended period of time – for example, dehydration, hypothermia, pneumonia, pressure sores, unavoidable incontinence and even death[80]. This inability to get up has a poor prognosis in terms of hospitalisation and mortality[80], thus, a long lie is one of the most serious consequences of a fall. The responsibility of the physiotherapist is to ensure the patient has a plan should they fall and are unable to rise and educate them about available strategies to combat this[81].

Backward-chaining is a method utilised to re-educate patients in rising from the floor unassisted. It consists of a sequence of movements combined together to help teach someone to be able to get down to the floor safely. Once learnt, the sequence is reversed and is applied to teach a safe and effective way to get up from the floor. The movement is broken into several stages depending on the patient’s ability. The patient will complete one stage, then return to a stand. Then they will add on the next stage and return to a stand. This is repeated until the patient is able to stand from lying on the floor.

The effect of backward-chaining on an individual’s ability to rise unassisted from the ground has been proven to be beneficial. In the only study to compare backward chaining with a control of conventional therapy, it was found that the backward-chaining method significantly enhances ability in rising after an incidental fall (20-40%)[83]. The control group showed no improvement. The study took part over 12 weeks and included 120 participants aged 80-99. Additionally, Timed Up and Go and Tinetti measurements were also compared before and after the intervention and control and a notable improvement was only observed from the intervention group. This highlights the benefits for improving functional capabilities in addition to rising abilities.

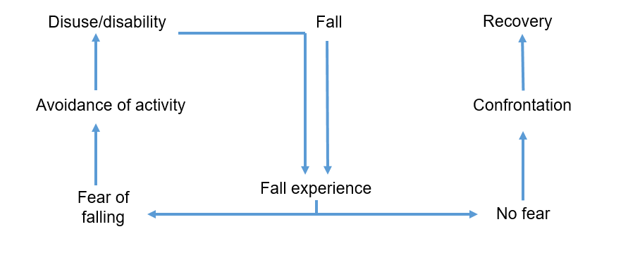

Fear of Falling[edit | edit source]

The prevalence of fear of falling in community-dwelling older adults ranges between 12% and 65%[84]. Whilst it frequently occurs after falls[85], it is also established in those without a fall history[86]. It can lead to a loss of independence, activity restriction and ultimately a poorer quality of life[87]. Not all will avoid ADLs due to fear but for those who do, it can have debilitating and devastating effects[88]. Lethem et al[89] introduced the psychiatric concept of a fear avoidance model and is it is commonly utilised in the prevention of acute musculoskeletal pain becoming chronic[90]. However, the hypothesis behind the model can be adapted to explain fear of falling and avoidance of activity. Extreme avoidance can lead to a decline in physical function, and ultimately an increased risk of falls, further fuelling fear and avoidance of activities. This is illustrated in the below fear avoidance model, adapted from Lethem et al[89].

The physiotherapist is in an ideal position to steer the individual towards the route of confrontation and recovery as opposed to activity avoidance and disability[59]. There is high quality evidence from two systematic reviews highlighting the benefits of treatment to improve confidence and reduce fear of falling[91][92]. Recommended interventions include: exercise, including tai chi, and multi-component falls prevention programmes.

Multi-Component Falls Prevention Programmes[edit | edit source]

As most falls are multifactorial in origin, they usually require several interventions[93]. Such interventions typically involve a combination of medication review and optimisation and education, environmental modification and exercise. This type of programme would be delivered by a multidisciplinary team in which the physiotherapist would be a key member. A Cochrane systematic review suggests that the physiotherapy treatment should combine all elements mentioned above; that is strengthening, balance, backward chaining, tai chi and confidence building with education, tailored to each individual. Clinic-based group exercise or individual exercise in the home setting is suitable. However, further research is needed into the effectiveness of medication management in preventing falls[76].

Additionally, in a systematic review, it was reported that for the greatest effect, exercise programmes should include a high level challenge to balance, alongside strength and walking training[67]. However, brisk walking training should not be prescribed to those at a high risk of falls. Furthermore, it was found that exercise should not only target those at high risk but also the general community and it should be performed for at least two hours per week on an ongoing basis.

Self-Management[edit | edit source]

For many people, older age is associated with long term conditions such as heart failure, dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and diabetes. As we know, an element of frailty is the decreased ability to withstand illness. Exacerbation of chronic conditions, an acute illness or a combination of both can trigger acute disability in frail older people and cause hospitalisation or institutionalisation[94]. Emergency hospital admissions is a major concern for the NHS. There are a number of factors associated with increased rates of admission including area of residency, ethnicity, socio-economic deprivation and environmental factors. Older people are also identified as being at a higher risk of hospital admittance[95].

In Scotland, 40% of the population have at least one long term condition (LTC). People with LTCs and co-morbidities are known to have poorer clinical outcomes, poorer quality of life and longer hospital stays[96]. The Scottish Government[97] reports that people with LTCs are twice as likely to be admitted to hospital. The ageing population and the increased prevalence of LTCs requires healthcare professionals to move their focus towards preventative strategies and empowering self-management[98].

Physiotherapist's have a role in promoting self-management of long term conditions and physical activity. Disease-related self-management abilities such as taking medication and exercise are often promoted by health care professionals. However, there may also be a need for interventions aimed at self-management of overall health and well-being to contribute to healthy ageing[99]. Older peoples’ abilities to self-manage the effects of the ageing process depends on physical, psychological and social aspects of their life[100]. Physiotherapists working with frail older people could play a role in promoting healthy ageing. Evidence shows that interventions to promote healthy ageing can be used to the delay the onset of frailty and reduce its adverse outcomes among older people[100].

As older people often have co-morbidities leading to a mixture of physical and psychosocial issues, self-management interventions should focus on providing them with general behavioural and cognitive skills for dealing with range of problems, rather than focusing on health-related problems only[99]. It is outwith the scope of this learning resource to go into detail about how to promote self-management strategies as you are likely to see a range of diverse patients presenting with multiple conditions and challenging psychosocial issues. Your treatment plan will depend on the patient's presenting condition. However, as physiotherapists, we believe our main role within self-management can be to promote physical activity to contribute to the healthy ageing process.

Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

Functional capacity declines with age and this is further accelerated by low levels of physical activity.

The recommendations for physical activity for older adults (65+)[101]:

- Older adults should aim to be active daily

- At least 150 minutes a week of moderate intensity activity

- Muscle strength training twice a week in addition to the 150 minutes of activity

- Balance training and co-ordination should be incorporated into activities to manage risk of falls

- Minimise sedentary time

Physical activity significantly decreases with age. The graph below shows the percentage of men and women meeting the physical activity recommendations in Scotland[102].

Benefits of Physical Activity in Frail Older Adults[edit | edit source]

Strength, endurance, balance and bone density is lost at a rate of 10% per decade, while muscle power reduces at around 30% per decade[103]. Sarcopenia is highly prevalent among older adults and has been identified as a risk factor for frailty[104]. Being physically active slows down these physiological changes associated with ageing. Physical activity can also reduce the risk of falls, promote cognitive health and self-management of chronic diseases. It can also slow down the deterioration in ability to perform ADLs and maintain quality of life in older adults[105][106]. A meta-analysis[105] found that exercise is beneficial to improve balance, gait speed and abilities to carry out ADLs in the frail older adult population.

Factors Influencing Participation in Physical Activity in Older Adults[edit | edit source]

Older peoples’ participation in physical activity can be effected by biological, demographic, physiological and social factors. These factors are important to be aware of when attempting to motivate older people to increase their activity levels.[107]

- Men are more active than women

- A decline in physical activity with age is higher among: minority ethnic groups, those from lower socio-economic backgrounds, those with lower education and those living alone

- Older people might be less able due to pain, reduced mobility and the need of assistance to mobilise[106]

- Physical activity can be influenced by trusted others such as health care professionals, care givers, family and friends

- Lack of transport often affects older people's abilities to part take in activity

Physiotherapists Role in Promoting Physical Activity in Frail Older Adults[edit | edit source]

Due to their training and experience, physiotherapists are in a good position to promote health and well-being of individuals and the community through education on physical activity and exercise prescription[108]. Recently there has been a shift in the general public's health agenda towards the prevention of chronic conditions and enabling the ageing population to stay active and manage conditions in the community. This has required a change in the role of the physiotherapist towards addressing these issues through promotion of physical activity and other lifestyle changes[109]. When encouraging physical activity, physiotherapists should also aim to[110]:

- Identify fears and barriers to being physically active and provide solutions to overcome these

- Provide ongoing support and encouragement

Exercises for Frail Older Adults[edit | edit source]

These are the recommended activities and intensity for frail older adults to increase physical activity. These aim to improve general health and well being, as well as reduce the risk of falls and manage chronic lifestyle conditions:

- Sessions as short as 10 minutes can provide health benefits[103]

- Frail older adults should aim to accumulate numerous 10 minute sessions to achieve the recommended activity guides[111]

Suggested activities:

- Take the stairs[101]

- Walking[101]

- Do housework or gardening[101]

- Tai Chi[111]

- Dance[111]

- Swimming[101]

- Home-based or group exercise classes[103]

- Breaking up time spent sitting with short regular periods of standing or walking[111]

- Encourage to move for longer. E.g. Going from moving 5 minutes to 10 minutes may increase the intensity[111]

A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials[112] suggested that a low dose of creatine monohydrate along with resisted exercises may improve upper and lower extremities strength in healthy older adults.

Motivation[edit | edit source]

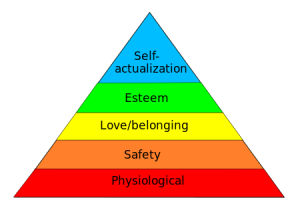

Motivation can be defined as the processes that explain an individual’s intensity, direction and persistence of effort towards

achieving a goal. Motivation often stems from a need we must fulfil and this leads to a specific behaviour[113]. In 1943, Maslow developed a theory of human motivation aiming to explain and rank all types of human needs[114]. Maslow’s Hierarchy model is made up of five levels ranked in importance with the most basic needs at the bottom. In order to progress up the hierarchy, the lower needs must be fulfilled.

Depending on your preferred ways of learning, choose if you want to read or watch the video below to learn more about the Maslow’s Hierarchy.

There are many factors that motivate the elderly to participate in exercise programs, see below[106].

It is important to note that studies have found a correlation between those with a previously active lifestyle and those who were more likely to perform exercise programs[106] supports this idea of goal setting within the elderly population. Without goals, adherence to exercise is limited. The literature again reinforces the fundamentals of effective goal setting:

- Patient-centred goals

- Small goals incrementally increasing to large goals e.g. short term and long term

- Should adhere to SMART principles

Despite the need to motivate it is also important to listen to the patient and their needs. One of the ways we can encourage motivation is by arranging a group exercise class, as this not only promotes the physical benefits of exercise, but allows participation in a social gathering[116]. Furthermore, research suggests that people are more likely to exercise if they have a companion[117].

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

The average age of the population is increasing and it is suggested that the prevalence of frailty will multiply[118]. Subsequently, there has been a shift of care from reactive to preventative strategies and a focus on providing early interventions to reduce costly unplanned admissions to hospital[119]. Several guidelines are available, but none specifically detail the physiotherapist's role.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Introduction to Frailty

- ↑ British Geriatrics Society. Fit For Frailty: Part 1: Recognition and management of frailty in individuals in community and outpatient settings. http://www.bgs.org.uk/index.php/fit-for-frailty (accessed 12 Oct 2015)

- ↑ Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol Ser A-Biol Sci Med Sci 2001; 56; 146-56

- ↑ Xue QL. The Frailty Syndrome: Definition and Natural History. Clin Geriatr Med 2011; 27: 1-15

- ↑ Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert M, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet (London, England). 2013 Feb 12 [cited 2016 Jan 27];9868(381). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23395245.

- ↑ The King’s Fund. Making our health and care systems fit for an ageing population. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/making-health-care-systems-fit-ageing-population-oliver-foot-humphries-mar14.pdf (accessed 28 Jan 2016)

- ↑ WHO Ageing and health Available:https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed 13.11.2022)

- ↑ Tabata K. Population aging, the costs of health care for the elderly and growth. Journal of Macroeconomics. 2005 Sep 1;27(3):472-93. Available:https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0164070405000303 (accessed 13.11.2022)

- ↑ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health at a Glance, 2013. http://www.oecdilibrary.org/docserver/download/8113161e.pdf?expires=1444911042checksum=AAD68253A0B959E184ACCEE3FFE37481 (accessed 16 Oct 2015).

- ↑ Australia Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s hospitals 2013-14: at a glance http://www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=60129551482 (accessed 20 Dec 2015).

- ↑ Weiss, A. J., And Elixhauser, A., 2014. Overview of Hospital Stays in the United States, 2012. Online from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb180-Hospitalizations-United-States-2012.jsp (accessed 4 Jan 2016).

- ↑ National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Dementia, disability and frailty in later life – mid-life approaches to delay or prevent onset. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2015

- ↑ NHS Choices. Physiotherapy. http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/Physiotherapy/Pages/Introduction.aspx (accessed 20 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Crane J, Delany C. Physiotherapists in emergency departments: responsibilities, accountability and education. Physiotherapy 2013; 99; 2: 95-100

- ↑ Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Physio and paramedic pool resources in Lakes initiative. http://www.csp.org.uk/news/2015/10/12/physio-paramedic-pool-resources-lakes-initiative (accessed 20 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Anaf S, Sheppard LA. Describing physiotherapy interventions in an emergency department setting: an observational pilot study. Accident and emergency nursing 2007; 15:1:34-9

- ↑ Arendts G, Fitzhardinge S, Pronk K, Donaldson M, Hutton M, Nagree Y. The impact of early emergency department allied health intervention on admission rates in older people: a non-randomized clinical study. BMC Geriatrics 2012; 12:8

- ↑ Hsieh TJ, Su SC, Chen CW, Kang YW, Hu MH, Hsu LL, Wu SY, Chen L, Chang HY, Chuang SY, Pan WH. Individualized home-based exercise and nutrition interventions improve frailty in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2019 Dec 1;16(1):119.

- ↑ NHS. Arthritis Research UK: Painkillers (analgesics).http://www.nhs.uk/ipgmedia/national/Arthritis%20Research%20UK/Assets/Painkillers-analgesics.pdf (accessed 9 Jan 2016)

- ↑ NHS. Beta- Blockers. http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Beta-blockers/Pages/Introduction.aspx (Accessed 5 Jan 2016)

- ↑ NHS. Antidepressants. http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Antidepressant-drugs/Pages/Introduction.aspx (Accessed 2 Jan 2016)

- ↑ NHS. Generalised anxiety disorder in adults - Treatment. http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Anxiety/Pages/Treatment.aspx (Accessed 3 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Mayo Clinic, Diseases and Conditions:High blood pressure (hypertension). http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/high-blood-pressure/in-depth/angiotensin-ii-receptor-blockers/art-20045009 (accessed 9 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Mayo Clinic, Diseases and Conditions: Diuretics. http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/high-blood-pressure/in-depth/diuretics/art-20048129 (Accessed 4 Jan 2016).

- ↑ NHS Choice, Anticoagulant medicines. http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/Anticoagulant-medicines/pages/side-effects.aspx (accessed 19 Jan 2016)

- ↑ The King’s Fund. Polypharmacy and medicines optimization – making it safe and sound. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/polypharmacy-and-medicines-optimisation-kingsfund-nov13.pdf (accessed 20 Jan 2016)

- ↑ Sullivan G and Lansbury G. Physiotherapists’ knowledge of their clients’ medications: A survey of practicing physiotherapists in New South Wales, Australia. 2009;15: 191-198. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/095939899307748 (accessed 18 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Needle JJ, Petchey RP, Benson J, Scriven A, Lawrenson J, Hilari K. The allied health professions and health promotion: a systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. Final report. NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation programme;2011.

- ↑ Theou O, Jones GR, Overend TJ, Kloseck M, and Vandervoort AA. An exploration of the association between frailty and muscle fatigue. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2008; 33: 651–665. http://www.researchgate.net/publication/51415786_An_exploration_of_the_association_between_frailty_and_muscle_fatigue (accessed 4 Jan 2016).

- ↑ NHS Southern Health. Inpatient services - older people's mental health. http://www.southernhealth.nhs.uk/services/mental-health/older/inpatient/ (accessed 20 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Salthouse TA. When does age-related cognitive decline begin? Neurobiol Aging 2009; 30: 507-14

- ↑ Barberger-Gateau P, Fabrigoule C. Disability and cognitive impairment in the elderly. Disabil Rehabil 1997; 19: 5 :175-93.

- ↑ Kaur J, Masaun M, Bhatia MS. Role of physiotherapy in mental health disorders. Delhi Psychiatry Journal 2013; 16: 2: 404-8

- ↑ Department of Health. Common Assessment Framework for Adults: a consultation on proposals to improve information sharing around multi-disciplinary assessment and care planning. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Consultations/Closedconsultations/DH_093438 (accessed 4 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Horowitz B P. Supporting community living through client-centered care. Occupational therapy in mental health; 2002 : 18(1).

- ↑ World Health Organization. ICIDH-2: International classification of functioning, disability, and health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001.

- ↑ Norton J, Ancelin ML, Stewart R, Berr C, Ritchie K, Carrière I. Anxiety symptoms and disorder predict activity limitations in the elderly. Journal of Affective Disorders 2012; 141(2/3): 276-285.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Nilsson I, Nyqvist F, Gustafson Y and Nygård M. Leisure Engagement: Medical Conditions, Mobility Difficulties, and Activity Limitations—A Later Life Perspective. Journal of Aging Research; 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/610154 (accessed 04 Jan 2016).

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 Cambois E, Robine J-M, Romieu I. The influence of functional limitations and various demographic factors on self-reported activity restriction at older ages. Disability and Rehabilitation 2005; 27(15): 871 – 883.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Makizako H, Shimada H, Doi T, Tsutsumimoto K, Lee S, Hotta R, et al. Cognitive Functioning and Walking Speed in Older Adults as Predictors of Limitations in Self-Reported Instrumental Activity of Daily Living: Prospective Findings from the Obu Study of Health Promotion for the Elderly. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015; 12: 3002-3013. www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/12/3/3002/pdf (accessed 20 Dec 2015).

- ↑ Qu W, Stineman, MG, Streim J E, Dawei Xie D. Understanding Linkages between Perceived Causative Impairment and Activity Limitations among Older People Living In the Community. A Population-Based Assessment. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2011; 90(6): 466–476.

- ↑ Mast BT, Azar AR, MacNeill SE, Lichtenberg PA. Depression and activities of daily living predict rehospitalization within 6 months of discharge from geriatric rehabilitation. Rehabilitation Psychology 2004; 49(3): 219-223.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Petty, NJ. Neuromusculoskeletal examination and assessment: a handbook for therapists. Edinburgh : Churchill Livingstone, 2011.

- ↑ Cott, CA. Goal setting. In: Pickles B et al, editor. Physiotherapy with older people. London: WB Saunders company ltd, 1995.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Wagstaff P and Coakley D. Physiotherapy and the elderly patient. Kent: Croom Helm ltd, 1988.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Arnadottir S A, Gunnarsdottir E D, Stenlund H and Lundin-olsson L. Participation frequency and perceived participation restrictions at older age: applying the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework. Disability and rehabilitation 2011; 33(22-23): 2208-2216.

- ↑ Crews JE and Campbell VA. Health Conditions, Activity Limitations, and Participation Restrictions Among Older People with Visual Impairments. Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness 2001; 95(8):453-467.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Fairhall N, Sherrington C, Kurrle S E, Lord S R and Cameron I D. ICF participation restriction is common in frail, community-dwelling older people: an observational cross-sectional study. Physiotherapy [serial online]. 2011 [cited 2016 Jan 11]; 97(1):26-32. Available from: Wiley online library.

- ↑ Wilkie R, Peat G, Thomas E, Croft P. The prevalence of person-perceived participation restriction in community-dwelling older adults. Qual Life Res. 2006;15: 1471–1479.

- ↑ Wilkie R, Thomas E, Mottram S, Peat G, Croft P. Onset and persistence of person-perceived participation restriction in older adults: a 3-year follow-up study in the general population. Health Qual Life Outcomes [serial online]. 2008 [cited 2016 Jan 11];6(92). Available from: www.biomedcentral.com

- ↑ Wilkie R, Peat G, Thomas E, Croft P. Factors associated with restricted mobility outside the home in community-dwelling adults ages fifty years and older with knee pain: An example of use of the international classification of functioning to investigate participation restriction. Arthritis Care and Research. 2007; 57 (8): 1381-1389.

- ↑ Mearns N, Duguid I. Physiotherapy and Occupational Therapy in the Acute Medical Unit: Guidelines for Practice. http://www.acutemedicine.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/10.2-PTOT-AMU-Guidance-Document-2015.pdf (accessed 13 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Philp I. A recipe for care – not a single ingredient. London: Department of Health, 2007.

- ↑ Albert M, McCaig LF, Ashman JJ. Emergency department visits by person aged 65 and over: United States, 2009-2010. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2013

- ↑ Rothschild JM, Bates DW, Leape LL. Preventable medical injuries in older patients. Archives of Internal Medicine 2000; 160; 2717-28

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Age UK. Stop Falling: Start Saving Lives and Money. London: Age UK, 2010.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Gowing R, Jain MK. Injury patterns and outcomes associated with elderly trauma victims in Kingston, Ontario. Can J Surg 2007; 50; 437-44

- ↑ Scottish Government. Up and About or Falling Short? – A Report of the Findings of a Mapping of Services for Falls Prevention in Older People. Edinburgh: Scottish Government, 2012.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 CSP. Physiotherapy works: Falls and frailty. http://www.csp.org.uk/professional-union/practice/evidence-base/physiotherapy-works/falls-and-frailty (accessed 8 Jan 2016)

- ↑ Sousa AS, Guerra RS, Fonseca I, et al. Sarcopenia and length of hospital stay. Eur J Clin Nutr 2015.

- ↑ Azeem K, Al Almeer A. Effect of weight training programme on body composition, muscular endurance, and muscular strength of males. Annals of Biological Research 2013; 4; 154-6

- ↑ Burton LA, Sumakadas D. Optimal management of sarcopenia. Clin Interv Aging 2010; 5; 217-28

- ↑ Liu CJ, Latham NK. Progressive resistance training for improving physical function in older adults (Cochrane review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; (3); CD002759

- ↑ Seynnes O, Fiatarone Singh MA, Hue O. Physiological and functional responses to low-moderate versus high-intensity progressive resistance training in frail elders. J Gerontol Ser A-Biol Sci Med Sci 2004; 59A; 503-9

- ↑ Latham NK, Anderson CS, Lee A, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of quadriceps resistance exercise and vitamin D in frail older people: The frailty interventions trail in elderly subjects (FITNESS). J Am Geriatr Soc 2003; 51; 291-99

- ↑ Liu-Ambrose T, Khan KM, Eng JJ, et al. Both resistance and agility training reduce fall risk in 75-85 year old women with low bone mass: a six-month randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52; 657-65

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Sherrington C, Tiedemann A, Fairhall N, et al. Exercise to prevent falls in older adults: an updated meta-analysis and best practice recommendations. New South Wales Public Health Bulletin 2011; 22; 78-83

- ↑ Rubenstein, LZ. Falls in older people: epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for prevention. Age and Ageing 2006; 35.

- ↑ El-Khoury F, Cassou B, Latouche A, et al. Effectiveness of two-year balance training programme on prevention of fall induced injuries in at risk women aged 75-85 living in community: Ossebo randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2015; 22.

- ↑ Laufer Y, Dar G, Kodesh E. Does a Wii-based exercise program enhance balance control of independently functioning older adults? A systematic review. Clin Interv Aging 2014; 9; 1803-13

- ↑ Fu AS, Gao KL, Tung AK, et al. Effectiveness of exergaming training reducing risk and incidence of falls in frail older adults with a history of falls. Phys Med Rehabil 2015; 96; 2096-102.

- ↑ NHS Choices. A guide to tai chi. http://www.nhs.uk/Livewell/fitness/Pages/taichi.aspx (accessed 8 Jan 2016)

- ↑ Song R, Ahn S, So H, et al. Effects of t’ai chi on balance: a population-based meta-analysis. J Altern Complement Med 2015; 21; 141-51

- ↑ Li F, Duncan TE, Duncan SC, et al. Enhancing the psychological well-being of elderly individuals through tai chi exercise: A latent growth curve analysis. Structural Equation Modelling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 2001; 8; 53-83

- ↑ Kang JW, Lee MS, Posadzki P, et al. T’ai chi for the treatment of osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2009; 1.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community (Cochrane review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; (2): CD007146

- ↑ Campbell AJ, Robertson MC for the New Zealand Accident Compensation Corporation. Otago Exercise Programme to prevent falls in older adults. 2003. Accessed 2 October 2018.

- ↑ Sherrington C, Tiedemann A, Fairhall N, Close JCT, Lord SR. Exercise to prevent falls in older adults: an updated meta-analysis and best practice recommendations. NSW Public Health Bulletin. 2001,22;3–4: 78-83. Accessed 13 October 2018.

- ↑ Skelton D, Dinan SM, Campbell M, et al. Tailored group exercise (Falls Management Exercise – FaME) reduces falls in community-dwelling older frequent fallers (an RCT). Age Ageing 2005; 34; 636-639

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Tinetti ME, Liu WL, Claus EB, et al. Predictors and prognosis of inability to get up after falls among elderly persons. JAMA 1993; 269; 65-70

- ↑ Reece A, Simpson JM. Teaching elderly people how to cope after a fall. Physiotherapy 1996; 82; 27-35

- ↑ NHS Sutton and Merton Community Services. Getting on and off the floor safely. London: Staying Steady Falls Prevention Service, 2012

- ↑ Zak M, Skalska A, Szczerbinska K. Instructional programmes on how to rise unassisted effectively after sustaining an incidental fall, designed specifically for the elderly: a randomized, controlled trial. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil 2008; 10; 496-507

- ↑ Legters K. Fear of falling. Phys Ther 2002; 82; 264-272

- ↑ Tinetti ME, Medes de Leon CF, Doucette JT, et al. Fear of falling and fall-related efficacy in relationship to functioning among community-living elders. Journal of Gerontology Medical Sciences 1994; 49; 140-7

- ↑ Vellas BJ, Wayne SJ, Pomero LI, et al. Fear of falling and restriction of mobility in elderly fallers. Age Ageing 1997; 26; 189-93

- ↑ Donoghue OA, Cronin H, Savva GM, et al. Effects of fear and falling and activity restriction on normal and dual task walking in community dwelling older adults. Gait and Posture 2013; 38; 120-4

- ↑ Delbaere K, Crombez G, Vanderstraeten G, et al. Fear-related avoidance of activities, falls and physical frailty. A prospective community-based cohort study. Age and Ageing 2004; 33; 368-73

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 89.2 Lethem J, Slade PD, Troup JD, et al. Outline of a fear-avoidance model of exaggerated pain perception – I. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1983; 21; 401-8

- ↑ Leeuw M, Goossens MEJB, Linton SJ, et al. The fear-avoidance model of musculoskeletal pain: Current state of scientific evidence. Journal of Behavioural Evidence 2007; 30; 77-94.

- ↑ Zijlstra GAR, van Haastregt JCM, van Rossum E. Interventions to reduce fear of falling in community-living older people: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55; 603-15

- ↑ Rand D, Miller WC, Yiu J, et al. Interventions for addressing low balance confidence in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2011; 40; 297-206

- ↑ Hausdorff JM, Nelson ME, Kaliton D, et al. Etiology and modification of gait instability in older adults: a randomised controlled trial of exercise. J Appl Phys 2001; 90; 2117-29

- ↑ Healthcare Improvement Scotland. Improving the identification and management of frailty. http://www.healthcareimprovementscotland.org/our_work/person-centred_care/opac_improvement_programme/frailty_report.aspx (accessed 19 Nov 2015)

- ↑ The King's Fund. Avoiding hospital admissions: What does the research evidence say?. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/avoiding-hospital-admissions (accessed 11 Jan 2016)

- ↑ The King's Fund. Managing people with long-term conditions. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_document/managing-people-long-term-conditions-gp-inquiry-research-paper-mar11.pdf (accessed 17 Nov 2015)

- ↑ The Scottish Government. Long Term Conditions. http://www.gov.scot/Topics/Health/Services/Long-Term-Conditions (accessed 20 Nov 2015)

- ↑ The King's Fund. Transforming our health care system. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/articles/transforming-our-health-care-system-ten-priorities-commissioners (accessed 11 Jan 2016)

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 Cramm JM, Hartgerink JM, Steyerberg EW, Bakker TJ, Mackenbach JP, Nieboer AP. Understanding older patients’ self-management abilities: Functional loss, self-management, and well-being. Qual Life Res, 2013;22:85–92. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22350532 (accessed 11 Jan 2016)

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 Cramm JM, Twisk J, Nieboer AP. Self-management abilities and frailty are important for healthy aging among community-dwelling older people; a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics 2014;14:28. http://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2318-14-28 (accessed 11 Jan 2016)

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 101.2 101.3 101.4 Department of Health. Start active, stay active: report on physical activity in the UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/start-active-stay-active-a-report-on-physical-activity-from-the-four-home-countries-chief-medical-officers (accessed 28 Oct 2015)

- ↑ The Scottish Government. The Scottish Health Survey 2012. Volume 1 – Main report. http://www.gov.scot/Publications/2013/09/3684 (accessed 28 Oct 2015)

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 103.2 The British Heart Foundation National Centre for Physical Activity and Health. Interpreting the UK physical activity guidelines for older adults in transition. http://www.bhfactive.org.uk/older-adults-resources-and-publications-item/39/429/index.html (accessed 17 Oct 2015)

- ↑ Jansen FM, Prins RG, Etman A, van der Ploeg HP, de Vries SI, van Lenthe FJ, Pierik, FH. Physical Activity in Non-Frail and Frail Older Adults. PLoS One 2015;10:1-15. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25910249 (accessed 27 Oct 2015)

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 Chou CH, Hwang CL, Wu YT. Effect of Exercise on Physical Function, Daily Living Activities and Quality of Life in the Frail Older Adults: A Meta Analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93:237-44.http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003999311008173 (accessed 16 Oct 2015)

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 106.2 106.3 Weeks LE, Profit S, Campbell B, Graham H, Chircop A, Sheppard-LeMoine D. Participation in Physical Activity: Influences Reported by Seniors in the Community and in Long-Term Care Facilities. Journal of Gerontological Nursing 2008;34:36–43. http://www.healio.com/nursing/journals/jgn/2008-7-34-7/%7Bf65345f8-58ac-4381-a607-f663b5d57d53%7D/participation-in-physical-activity-influences-reported-by-seniors-in-the-community-and-in-long-term-care-facilities (accessed 7 Jan 2016)

- ↑ The British Heart Foundation National Centre for Physical Activity and Health. Factors influencing physical activity in older adults. http://www.bhfactive.org.uk/resources-and-publications-item/18/404/index.html (accessed 11 Jan 2016)

- ↑ Verhagen E, Engbers L. The physical therapist’s role in physical activity promotion. Br J Sports Med 2009;43:99–101. http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/43/2/99.abstract (accessed 28 Oct 2015)

- ↑ Spijker J, MacInnes J. Population ageing: the timebomb that isn’t? BMJ 2013;347:1-5. http://www.bmj.com/content/347/bmj.f6598.full.pdf+html (accessed 11 Jan 2016)

- ↑ The British Heart Foundation National Centre for Physical Activity and Health. Physical activity interventions for older adults. http://www.bhfactive.org.uk/older-adults-resources-and-publications-item/18/405/index.html (accessed 13 Jan 2016)

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 111.2 111.3 111.4 The British Heart Foundation National Centre for Physical Activity and Health. Interpreting the UK physical activity guidelines for frailer older adults. http://www.bhfactive.org.uk/resources-and-publications-item/39/430/index.html (accessed 17 Oct 2015)

- ↑ Stares A, Bains M. The Additive Effects of Creatine Supplementation and Exercise Training in an Aging Population: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of geriatric physical therapy (2001). 2019 Feb.

- ↑ Lambro P, Kontodimopoulos N, Niakas D. Motivation and job satisfaction among medical and nursing staff in a Cyprus public general hospital. Human Resources for Health 2010; 8:1-9. http://www.human-resources-health.com/content/pdf/1478-4491-8-26.pdf (accessed 21 Jan 2016)

- ↑ Maslow AH. Motivation and personality. London: Methuen, 1954.

- ↑ Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O-4ithG_07Q (accessed 9 June 2019)

- ↑ Thomas B, Storey E. [place unknown: publisher unknown]. Motivating the elderly client in long-term care; 2015 Dec 28 [cited 2016 Jan 8]. Available from: http://physical-therapy.advanceweb.com/Article/Motivating-the-Elderly-Client-in-Long-Term-Care.aspx.

- ↑ Rosenfeld M. Motivational Strategies in Geriatric Rehabilitation. Bethseda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association; 1997.

- ↑ Karunananthan S, Wolfson C, Bergman H, Beland F, Hogan DB. A multidisciplinary systematic literature review on frailty: overview of the methodology used by the Canadian Initiative on Frailty and Aging. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:68.

- ↑ Edwards N. Community services - how they can transform care. London: The King's Fund, 2014.