Fostering Behaviour Change in Obese Adolescents: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 121: | Line 121: | ||

[[Image:Stages by principles and processes of change.PNG]] | [[Image:Stages by principles and processes of change.PNG]] | ||

==== Decisional Balance ==== | ==== Decisional Balance ==== | ||

Decisional balance is a core concept of the TTM and describes the pros and cons of changing a behaviour (DiClemente et al 1986, Jannis and Mann 1977). When progressing from one stage to another, especially in the earlier stages, the individual must believe that the pros of changing are at least equal to if not greater than the cons. Moving from pre-contemplation to action, the pros increase by one standard deviation and the cons decrease by half a standard deviation (Prochaska et al. 1998, Hall and Rossi 2008). In pre-contemplation, the cons outweigh the pros, are approximately equal in the contemplation stage, and the pros outweigh the cons in the Preparation and Action stage (Peterson 2009, Redding 2000). | Decisional balance is a core concept of the TTM and describes the pros and cons of changing a behaviour (DiClemente et al 1986, Jannis and Mann 1977). When progressing from one stage to another, especially in the earlier stages, the individual must believe that the pros of changing are at least equal to if not greater than the cons. Moving from pre-contemplation to action, the pros increase by one standard deviation and the cons decrease by half a standard deviation (Prochaska et al. 1998, Hall and Rossi 2008). In pre-contemplation, the cons outweigh the pros, are approximately equal in the contemplation stage, and the pros outweigh the cons in the Preparation and Action stage (Peterson 2009, Redding 2000). | ||

====Self Efficacy==== | |||

Self-efficacy is another core concept of the TTM. Bandura (1977) originally introduced the concept and defined it as the strength of an individual’s expectation. A more detailed definition being, “the individual’s belief in his or her capacity to execute behaviours necessary to produce specific performance attainments” (Bandura 1997). Self-efficacy has been found to be a very strong indicator of health behaviour performance in issues such as condom use and weight gain, with confidence being a stronger indicator of future behaviour than past experience (Redding et al. 2000, Galavotti et al. 1995). Research has shown that self-efficacy is low in the pre-contemplation and contemplation stages and is significantly higher in the action stage (Lechner and De Vries 1995, Prochaska 1995). Prochaska et al. (1994) found progressing from one stage of change to another builds confidence and therefore increases self-efficacy. | |||

====Application to practice==== | |||

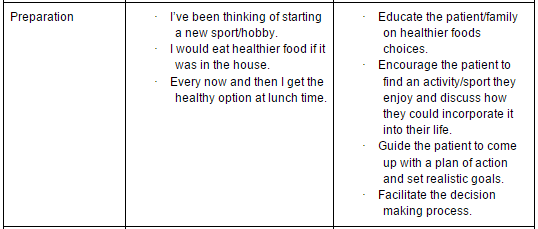

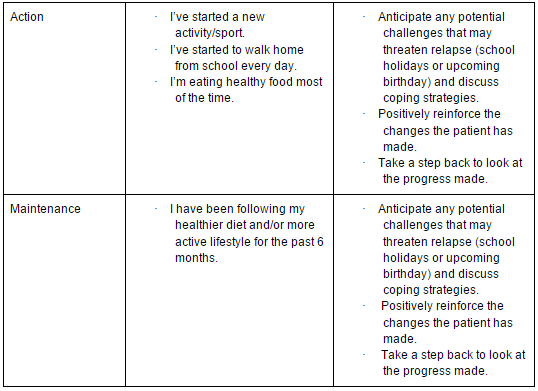

In order to select the intervention that is most suitable for a patient and their family, it is first important to identify which stage of change they are in. There have been a number of tools developed to help the clinician decide which stage their patient is in, such as the Stages of Exercise Behaviour Change (SEBC) scale (Marcus et al. 1992). Processes of change, decisional balance and self-efficacy can also be measured using tools developed in the 1990s (Marcus et al. 1992, Marcus et al. 1994). The table below gives a quick go-to guide to help identify and determine strategies for behaviour change (Mead Johnson 2015). | |||

[[Image:Application_to_practice_1.PNG]] | |||

[[Image:Application_to_practice_2.PNG]] | |||

[[Image:Application_to_practice_3.PNG]] | |||

[[Image:Application_to_practice_4.PNG]] | |||

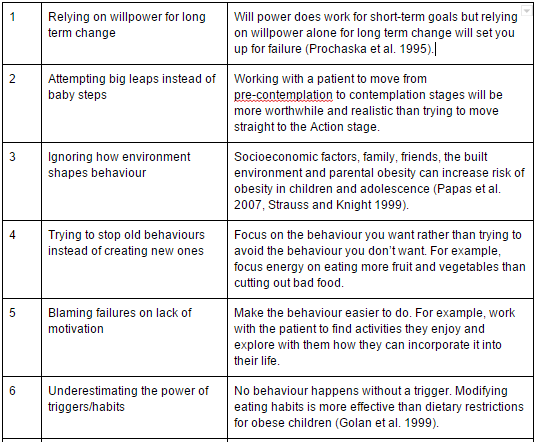

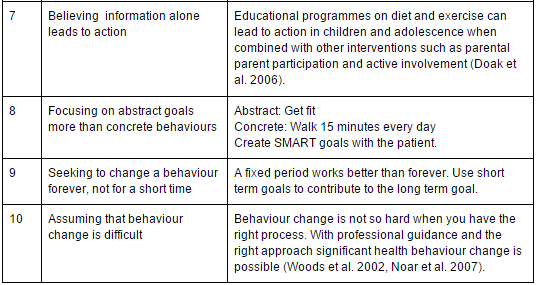

====Common mistakes made when changing behaviours====<br>The table below describes ten common mistakes that are made when trying to facilitate behaviour change (Stanford Persuasive Tech Lab 2010). | |||

[[Image:Common_mistakes_1.PNG]] | |||

[[Image:Common_mistakes_2.PNG]] | |||

=== Decisional Balance === | === Decisional Balance === | ||

Revision as of 18:36, 25 November 2015

Learning Aims[edit | edit source]

- Gain sufficient knowledge and skills to support adolescents and their families in changing behaviours to increase physical activity to initiate and maintain weight loss.

- To develop a set of competencies and skills and apply a variety of psychological techniques to foster patient centred behavioural change in adolescents

- Demonstrate understanding and empathy of adolescents attitudes towards obesity, to build a rapport and raise the issue of weight loss sensitively

- To ensure that the adolescent has sufficient information to allow them make an informed decision about the need to increase physical activity through a change in behaviour and awareness of the support options available

- Be able to clarify your role as a physiotherapist and recognise the boundaries of your scope of practice in an at risk adolescent population

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Background[edit | edit source]

Size of the problem[edit | edit source]

Global obesity levels have been on the rise over the past 3 decades; this is true for both males and females for all age groups,. According to recent figures, the average age at which individuals in the UK are becoming obese is decreasing. Researchers found clear trends with time, highlighting not only is the prevalence of obesity increasing but it is also becoming more common at an earlier age (Seidell and Halberstadt 2015).

Statistics[edit | edit source]

Obesity has more than doubled in children and quadrupled in adolescents in the past 30 years (CDC 2015) 31% of boys and 28% of girls aged 2-15 were classified as either overweight or obese in 2011 (National Obesity Forum, 2015) In 2012, more than 1/3 of children and adolescents were overweight or obese (CDC 2015) Latest figures for England show that ⅕ of children joining primary school are now overweight/obese (BBC 2015) Studies have shown adolescent obesity is directly associated with both maternal and paternal BMI and parental obesity is an independent risk factor for child/adolescent obesity (Svensson et al 2010) It has been reported that if one parent is obese, there is a 50% chance that their child will be also and if both parents are obese the risk rises to 80% (Aacap 2011).

Health Implications[edit | edit source]

It is known that obese children and adolescents often go on to be obese adults, putting them at risk of morbidity, disability and premature mortality in adulthood. Obesity can have significant effects on both our physical and mental health. Some of the obesity-related diseases often do not develop until later in life, such as degenerative arthritis, heart disease, stroke and various forms of cancer. However, there is a long list of other serious obesity-related medical conditions which can arise during the adolescent years, including:

•Cardiovascular (CVD) risk factors

◦Hypercholesterolemia

◦High triglyceride levels

◦Hypertension

•Musculoskeletal problems

•Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA)

•Asthma

•Pancreatitis

•Type 2 diabetes

•Psychological issues

Therefore, adolescent obesity is not a subject that should be taken lightly, and the list above highlights the serious need for intervention in this population (Must and Strauss 1999).

Psychosocial contributing factors to obesity in adolescents – the patient’s perspective[edit | edit source]

As physiotherapists, it is important that we take into consideration the whole picture and are able to grasp the patient’s perspective when any patient presents to us in clinical practice. This is essential when planning specific interventions for patients (Niemen et al 2012).

There are a variety of reasons why an adolescent may become overweight or obese. Psychosocial stressors which can result in emotional eating include bullying, experiencing neglect/maltreatment (Whitaker et al 2007), or living in an environment where there is a lack of consistency, food-limiting or general adult supervision (Cohen 2002).

When young people become stressed, they are more likely to overeat or comfort eat. Other examples of stressors can be parents divorcing/separating and physical or mental abuse, resulting in the adolescent turning to food as a coping mechanism. Chronic stress can lead to poor sleeping patterns, tiredness and a lack of motivation to participate in regular physical activity. This creates a vicious cycle as insufficient sleep is associated with the development of obesity (Ievers-Landis et al 2008).

Overweight adolescents are often made fun of and bullied, making it challenging for them to make friends. There is a often a negative stigma attached to obesity, especially in the thin-obsessed culture we live in. Teasing and bullying, which make the adolescent feel uncomfortable, can make it hard for them to lose weight and can cause them to gain more weight as they may turn to food for comfort. Low self-esteem and a fear of being bullied can make adolescents less likely to exercise (Washington 2011).

It is often a combination of some of these things which can cause an adolescent to become obese, and it is vital that the physiotherapist takes these contributing factors into consideration when communicating with the patient.

Psychosocial effects of obesity[edit | edit source]

As briefly mentioned above, overweight and obese adolescents often endure harsh psychosocial consequences as a result of their weight. These include depression, bullying, social isolation, low self-esteem, negative body image and overall reduced quality of life.

Sometimes it can be difficult to determine whether depression is the cause or result of the obesity. This is where communication with the patient can be vital in order to determine the relationship between their obesity and depression. It has been established that the longer the adolescent is overweight or fails to lose weight, the higher the risk of developing depression and other mental health disorders. Depression leaves adolescents and people of all ages feeling less motivated to participate in physical activity (Pine et al 2001).

A negative body image can affect both mood and eating patterns, and can be emotionally damaging for young people, particularly in the world we live in today. It is important for young people especially to grow through adolescence being comfortable in their own skin and with their own identity. Adolescents who find it difficult to manage their weight can experience periods of very low self-esteem. As physiotherapists, it is essential that we use appropriate language and continue to encourage and motivate this type of patient (Vaidya 2006).

All of the above can result in the adolescents experiencing reduced quality of life, and a reduced ability to cope and manage daily life. Again, low quality of life is associated with poor physical activity engagement and a reduced perception of themselves as a person as a whole, feeding the vicious cycle of obesity (Niemen et al 2012).

Current Guidelines[edit | edit source]

The role of the physiotherapist is broadening as our population endures an obesity epidemic. Physiotherapists need to be well equipped to deliver patient centered care for adults, and more importantly, for an at risk adolescent population. It is understood that patients will not be referred to a physiotherapist to address their obesity, but more likely for a musculoskeletal issue.. This finding was reflected by Nye et al (2014) who revealed there was an increased hazard ratio for musculoskeletal injury in those with high-risk abdominal circumference. Although it isn't a causitave factor, obesity does have a strong correlation with musculoskeletal injuries. This research is important because it informs physiotherapists that by addressing obesity we may also be treating a musculoskeletal issue in our patients.

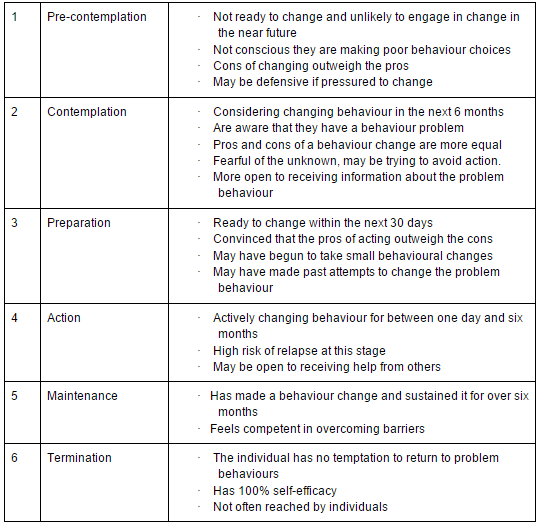

Under current treatment guidelines available to physiotherapists such as Chartered Society of Physiotherapists, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), the care given to patients who are obese is most often in the form of exercise prescription. While it is imperative that the patient changes the behaviours that are factors in their poor weight management, continuing to prescribe positive active lifestyles is critical to managing the patient's weight. The current guidelines reflect this sentiment and will be summarised below.

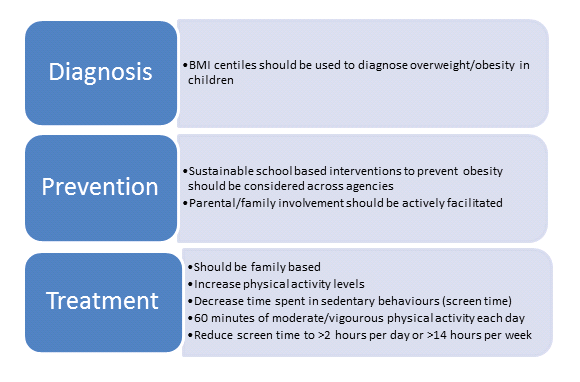

Figure _ - SIGN Guidelines

The SIGN guidelines indicate that if behaviours are to be changed in children and adolescents, it needs to come from all aspects of their life. The guidelines target interventions to occur in schools, within families, and between children in their hobbies. They require schools to make choices for their students that will promote physical activity such as physical education and active activities during breaks at school. It also specifies that parents should take an active role in their child's obesity and time in sedentary behaviours (>2 hours per day) while promoting active behaviours (60 minutes per day). (SIGN 2010).

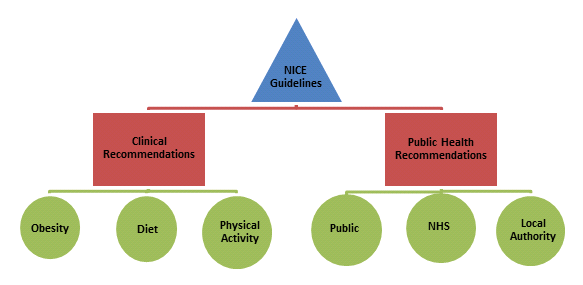

Figure _ - NICE Pathways

Table _ - NICE Guidelines

The NICE Guidelines above take a more personal approach to weight loss in adolescents compared to the SIGN guidelines. The review includes more subtle components such as positive feedback and reinforcement, such as praising a child for physical activity, even though they may not necessarily lose weight due to the effects on other health factors. While the guidelines also suggest increasing general physical activity to 60 minutes a day and reducing screen/sitting time, they recommend that children need to be given more opportunity and support in their activity in order to ensure they are confident in doing said activity (NICE 2006).

CSP proposed a brief treatment approach for care providers including physiotherapists as a primary method of changing behaviours in at risk individuals. The brief intervention guidelines recommend that physiotherapists identify inactive individuals and advise them to reach minimum amount of activity per week. As mentioned previously this includes approximately 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity, while 3 days per week should involve activities that strengthen muscle and bone. Activities that make up the 60 minutes a day include things that fit into their day easily. Examples of these include: walking or cycling to school, playing a sport through the school or at home, or popular activities such as WiiFit. The guidelines also recommend the physiotherapist “aim to improve people's belief in their ability to change (e.g verbal persuasion, modelling, or exercise behaviour).., and provide ongoing support, including written materials and goal setting (CSP, 2012).” The guidelines finally recommend an endorsement for pedometers, walking and cycling schemes to promote physical activity (CSP, 2012).

The current literature surrounding obese adolescents and physiotherapy care involves reducing energy intake, increasing physical activity while decreasing “screen time” (Clinical practice guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity in adults, adolescents and children in Australia, 2013). The Australian guidelines also recommend frequent contact with patients and family, and weight management is recommended for most children rather than weight loss. (Clinical practice guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity in adults, adolescents and children in Australia, 2013). Other research by Thury and de Matos (2015) indicated that school and family based interventions involving physical activity and dietary changes are the most likely interventions to be successful. Programs were also found to have more efficacy if they are longer in duration and focused on children in middle school or younger. A common theme between the 2 studies are that weight maintenance can be achieved via a behavioural change and the obese adolescent may be more motivated during adult years to adopt a healthier lifestyle and lose weight (Yager et al. 2002). Because obesity prevalence rates are increasing (SIGN 2010), the current guidelines attempt to slow the rate (i.e have people maintain their weight status), rather than gain or lose weight.

What is Behaviour Change?[edit | edit source]

Why is it important?[edit | edit source]

Models of Change[edit | edit source]

Trans-theoretical Model[edit | edit source]

The TTM is a model of behaviour change first developed in 1977 by James O. Prochaska to aid smokers in ceasing their negative and addictive behaviours. It has since been used in numerous studies across 12 different problem behaviours such as weight control, high-fat diets and quitting cocaine (Prochaska et al. 1994, Prochaska and DiClemente 1992). It has been used as a method to determine an individual’s readiness to change, progress through change and maintenance of new behaviours (Kidd et al. 2003, Peterson 2009), and has been described as an integrative and comprehensive model which builds upon a broad range of psychotherapy theories (Prochaska and Norcross 2001). The TTM consists of six stages of change and ten processes of change, with self-efficacy and decisional balance being central themes of the model (Prochaska et al. 1998). The TTM recognises change as a process that evolves over time with the individual moving through the series of stages. The time an individual spends at each stage can be variable but the step needed to be taken to move from one stage to another are not (ProChange Behaviour systems 2015). It is described as a cyclic change process rather than linear as individuals may progress through stages and then relapse many times before maintaining meaningful change (Noar et al. 2007). The physiotherapist can use the TTM to determine the stage a patient is in and then use the processes of change to facilitate progress through stages and reduce the probability of relapse (ProChange Behaviour systems 2015).

As described earlier, obesity and weight gain is a modern day epidemic and is growing in both the adult and adolescent populations. Problem behaviours such as weight gain and sedentary lifestyles often start in adolescence and when repeated over time, become habitual and part of an individual’s self-image (Kidd et al. 2002). By targeting an at risk adolescent population using TTM principles, physiotherapists may be able to invoke lifestyle changes that will be carried into adulthood (Prapavessis et al. 2006). The TTM is a model which is being used in clinical practice throughout the world across a broad range of populations including adolescents (Kidd et al. 2002, Woods et al. 2002, Prapavessis et al. 2006). Kidd et al. (2002) described the TTM as an appropriate and valid tool for use with an adolescent population, with several studies employing the model for changing risky behaviours exhibited by adolescents.

Stages of change and processes of change

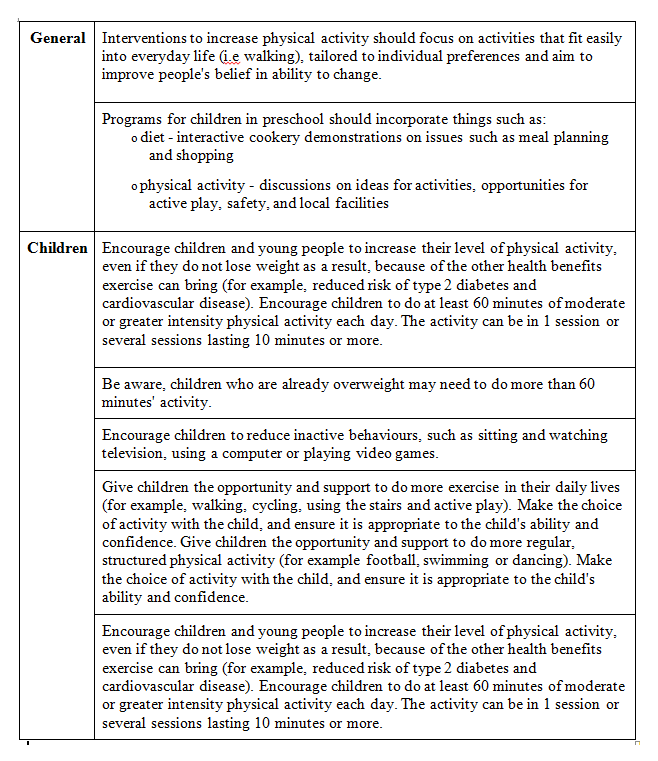

The six stages of change of the TTM are described in figure x (Kidd et al. 2002, Peterson 2009, Woods et al. 2002):

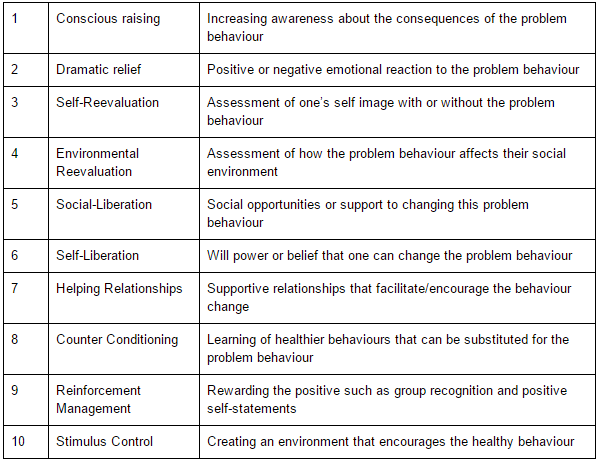

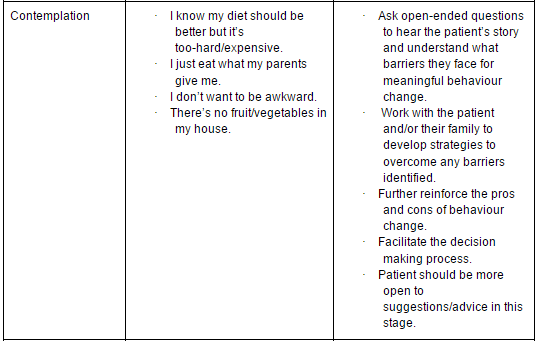

There are ten processes of change which are designed to act as facilitators to individuals moving between the stages of change. The ten processes of change are described in figure xx below (Virginia tech 2015, Prochaska et al. 1994):

The image shown below demonstrates where in the stages of change each process of change could be applicable (ProChange Behaviour Systems 2015):

Decisional Balance[edit | edit source]

Decisional balance is a core concept of the TTM and describes the pros and cons of changing a behaviour (DiClemente et al 1986, Jannis and Mann 1977). When progressing from one stage to another, especially in the earlier stages, the individual must believe that the pros of changing are at least equal to if not greater than the cons. Moving from pre-contemplation to action, the pros increase by one standard deviation and the cons decrease by half a standard deviation (Prochaska et al. 1998, Hall and Rossi 2008). In pre-contemplation, the cons outweigh the pros, are approximately equal in the contemplation stage, and the pros outweigh the cons in the Preparation and Action stage (Peterson 2009, Redding 2000).

Self Efficacy[edit | edit source]

Self-efficacy is another core concept of the TTM. Bandura (1977) originally introduced the concept and defined it as the strength of an individual’s expectation. A more detailed definition being, “the individual’s belief in his or her capacity to execute behaviours necessary to produce specific performance attainments” (Bandura 1997). Self-efficacy has been found to be a very strong indicator of health behaviour performance in issues such as condom use and weight gain, with confidence being a stronger indicator of future behaviour than past experience (Redding et al. 2000, Galavotti et al. 1995). Research has shown that self-efficacy is low in the pre-contemplation and contemplation stages and is significantly higher in the action stage (Lechner and De Vries 1995, Prochaska 1995). Prochaska et al. (1994) found progressing from one stage of change to another builds confidence and therefore increases self-efficacy.

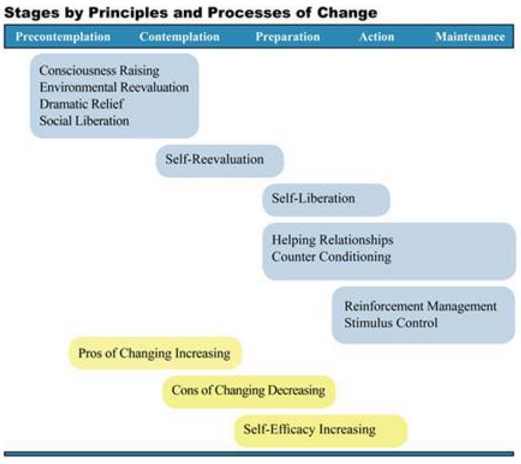

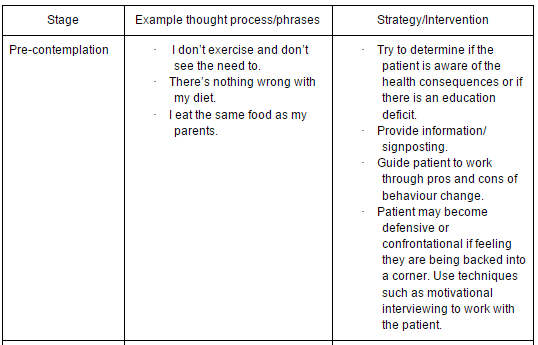

Application to practice[edit | edit source]

In order to select the intervention that is most suitable for a patient and their family, it is first important to identify which stage of change they are in. There have been a number of tools developed to help the clinician decide which stage their patient is in, such as the Stages of Exercise Behaviour Change (SEBC) scale (Marcus et al. 1992). Processes of change, decisional balance and self-efficacy can also be measured using tools developed in the 1990s (Marcus et al. 1992, Marcus et al. 1994). The table below gives a quick go-to guide to help identify and determine strategies for behaviour change (Mead Johnson 2015).

====Common mistakes made when changing behaviours====

The table below describes ten common mistakes that are made when trying to facilitate behaviour change (Stanford Persuasive Tech Lab 2010).

Decisional Balance[edit | edit source]

Attitudes and Perceptions[edit | edit source]

Interventions[edit | edit source]

Family Interventions[edit | edit source]

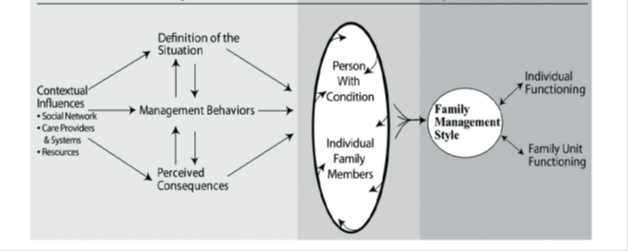

Conventional management of adolescent obesity should focus on behavioural modification that takes into account the influence of the food choices and physical activity levels of the adolescent’s family[1]. In order to support the adolescent through long-term maintenance of weight loss, parental confidence in supporting behaviour change is a crucial element of successful family based management efforts[2] It’s vitally important for a physiotherapist to consider the role parental behaviour, motivation, and confidence play in successful treatment and prevention of obesity[2]. A family management style framework (FMSF) can be utilised [3] in order to understand the family response to health related challenges and gain more of an understanding about how families can manage adolescent weight management within family life. This framework can be used to guide physiotherapists through the ability to recognise where family involvement can help to initiate and maintain weight loss and physical activity.

Jang & Whittenmore 2015. Reprinted with permission by Sage Publications. Knafl, Deatrick & Havill 2012

The way families with an overweight or obese adolescent ‘define the situation’ and manage the condition influences their approach to prevention or management of obesity [4]; the ‘situation’ refers to the parent perceptions about their adolescent’s weight status and their physical activity levels. This framework can be applied to many of the changes necessary to bring about weight loss but as physiotherapists, one of our key roles is to establish the problems associated with increasing physical activity and reducing sedentary behaviour.

In this framework, 'contextual influences' affecting the management of adolescent obesity include their social network, the health care practitioners and systems and their financial resources. It is important the adolescent is surrounded by a positive motivating environment, as interpersonal relationships, including family, peers and social networks can all influence health-related behavioural change in childhood[5]which is essential for future weight management. These supportive social networks can have a beneficial effect on adolescent’s physical activity levels, reducing sedentary behaviour.Furthermore, parent’s whose adolescents are overweight or obese tend to underestimate the severity of the problem. In turn, this attitude minimises the size of the problem and downplays the need to change health behaviours, seek advice, or explore and adopt weight management strategies.

Understanding the 'perceived consequences' associated with the adolescent’s health status is essential in highlighting the parent’s perceptions and beliefs about the effects of the adolescent’s condition on the adolescent and on family life. In addition, the perceived barriers related to physical activity must be taken into consideration before treatment commences. Safety issues related to outdoor activities may have an influence on the level and amount of physical activity undertaken. Certain environmental risks include pollutants, traffic and areas considered dangerous due to anti-social behaviour. Both adolescents and their parents need to be guided towards treatments and programs that limit any safety concerns applicable to them. Physiotherapists may find it difficult to broach the topic of sociocultural factors that may be playing a role. The high cost of organised sports programmes and club joining fees prohibits low socioeconomic families getting involved in such activities. This may be remedied by giving both the parents and their adolescent the support options available and the variety of complimentary programs available[6]

The centre for disease control and prevention (CDC) suggests that parents should play a role in physical activity promotion; they should help adolescents meet their activity goal by serving as role models incorporating exercise that is entertaining and agreeable into family life and actively encourage behaviour change that reduces sedentary activities such as watching television, playing video games, internet use and mobile phone use [7][8].

On initial assessment of an adolescent where a parent is present, the physiotherapist should gauge the parent’s degree of potential readiness to change. This can be classified using the transtheoretical model of change. It is imperative the parent(s) are willing to change in order for the adolescent to be adequately supported through a weight management programme [9].

Motivational Interviewing[edit | edit source]

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a directive, person-centred, counselling approach for bringing about behaviour change by helping individuals discover and resolve the absence of readiness to change behaviours. MI skills can be used to help the adolescent assess the benefits and drawbacks to their decisions and make an encouraging choice to change behaviour. This approach enhances the adolescent’s adherence to a behavioural intervention[10][11]and increases intrinsic motivation. The goal of MI is to create an atmosphere in which the individual rather than the physiotherapist becomes the main promoter and representative for change.

The main principles underpinning MI are:

- Expressing empathy: The physiotherapist must do this through reflective listening. See the world from the individual’s perspective.

- Developing discrepancy: Where is the individual now? And where do they want to be?

- Avoiding argumentation: The adolescent is responsible for change therefore the physiotherapist’s role is supportive and non-judgmental.

- Rolling with resistance: It is vital not to fight adolescent resistance but ‘’roll with it’’. Invite the adolescent to problem solve, acknowledge and explore their arguments against changing.

- Supporting self-efficacy: As a physiotherapist it is our job as part of a multidisciplinary team to help the adolescent find resources to implement new behaviours and overcome future barriers. Focus attention on the individual’s strengths and past successes[12][13]

A randomised control trial (RCT) highlighted that MI appeared to be a promising approach as an addition to a standard weight loss programme to promote physical activity in the context of adolescent obesity[12]. MI could be used as part of a physiotherapy treatment approach and it could be either incorporated into an initial assessment or carried out in a follow up session. A step by step approach can be taken similar to that used in the previous mentioned RCT[12].

- Stage 1: The physiotherapist should establish what the adolescent’s thoughts and attitudes are and promote his/her awareness of them. Building a confident relationship by addressing what is important in the adolescent’s life such as hobbies, social support and occupation. Once their interests have been considered, weight and physical activity related apprehensions, e.g. body image and sedentary behaviours, can be commenced. At this stage it is important to explore any worrying or negative beliefs about changing behaviour.

- Stage 2: Problem solving begins at this stage and once the adolescent has concluded that behaviour change is a necessity, alternatives to current behaviours are deliberated. The physiotherapist works alongside the adolescent to decide upon the type, duration and frequency of activity that could be performed. Depending on the patient’s goals and what they are willing to achieve, one or more alternative behaviours can be chosen.

- Stage 3: At this stage the physiotherapist and adolescent should set SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and timed) goals. Potential barriers to the weight loss plan and strategies to overcome these barriers can be discussed.

- Stage 4: The consequences of behaviour modification and adoption should be considered. Addressing any unforeseen barriers and any negative feelings toward new behaviours is finally discussed before commencement.

What to consider in practice?

- Empathetic listening skills

The physiotherapist’s job is not to jump ahead to any other topic but merely to allow the adolescent to explore this conflict.

- Eliciting self-motivating statements (Change Talk)

Instead of presenting arguments for change to the adolescent, the physiotherapist elicits these from the adolescent.

- Responding to resistance

The physiotherapist focuses on the issue to begin with, elicits defensiveness from an angry adolescent in response and then repairs the damage using reflective listening.

Example:

Physiotherapist: I understand that you have come to see me about the pain in your lower back, is that correct?

Adolescent: Yes, and everyone keeps telling me it is because I’m overweight and they have found no evidence of any damage. I tell you, if all you want to do is talk about is my weight, I may as well go home. It’s just a waste of my time.

In the dialogue that follows, the physiotherapist resists the temptation to argue back, and uses reflective listening to come alongside the adolescent and diffuse the tension.

Physiotherapist: For you, there’s a much bigger picture. It’s not just your weight that’s bothering you.

Adolescent: That’s right, because time and time again I get told that my weight is a problem, like it’s the only thing that matters.

Physiotherapist: Other things also matter and you don’t want them to be side-lined in our meeting today.

Adolescent: No that’s exactly right, I want to talk about other things as well.

Physiotherapist: Tell me, taking your time, about these other things.

[14]

Below is an example of motivational interviewing used to increase physical activity in an adolescent:

Goal Setting Theory[edit | edit source]

Central to any physiotherapy treatment is the need to set goals for your patients to achieve, a technique used to enhance motivation and engagement (McBean and Van Wijck, 2013). A goal has been described as “the object or aim of an action” (Latham & Locke 1991). Setting goals can facilitate behaviour change by channeling the attention of the patient towards improving their health and persistence. Two researchers found that greater goal commitment, ability, and self-efficacy to perform the tasks related to the goal were the biggest factors which maximized goal setting. Shorter term goals were found to be more useful than long (see SMARTER goals below) to promote self-efficacy especially in adolescents with shorter attention spans. Goal achievement can be enhanced by incorporating feedback following the completion of their activity or treatment (Abraham & Michie, 2008). A study from McEwan et al (2015) where the effect of goal setting on changing physical activity behaviour was reviewed, found a medium positive effect. They found benefits when the goal included moderate intensity physical activity or when the patient was free to to be active at any intensity they wished (McEwan et al 2015).

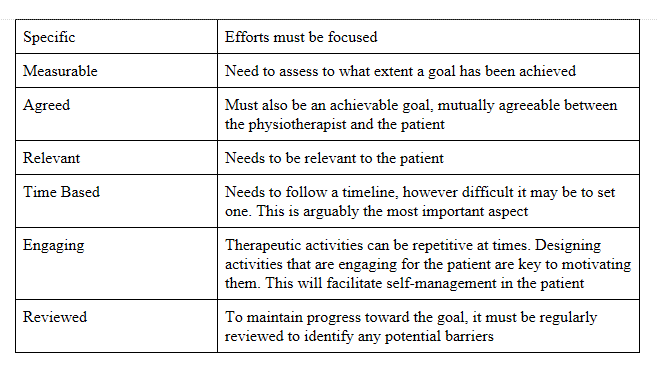

Current indications show that successful goals should follow the SMARTER acronym:

Table _ - SMARTER Goals Adapted from McBean and Van Wijck, 2013

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy[edit | edit source]

Behavioural Change Self-Management[edit | edit source]

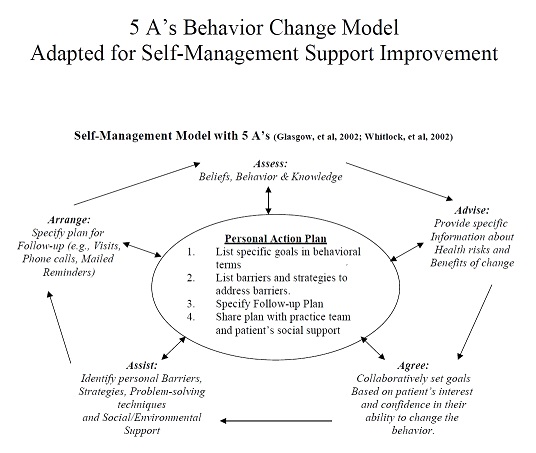

Self-Management (SM) is a vital component to maintain weight loss and physical activity participation. SM supports are used to prepare and empower people so they can manage their health effectively[15]. In order to support a SM plan the 5As Behaviour Change Model can be incorporated. This is a framework that will guide the physiotherapists in detection, assessment and management of diet and physical activity risk factors. This framework has been shown to improve patient outcomes in smoking cessation[16] and has shown positive results when used in weight loss management [17]. A recent study by Morais et al 2015 found that SM support structured according to the 5As, provided guidelines for a better SM approach in stroke patients. The 5As framework can be used in combination with other skills-based approaches such as MI to enhance adolescent interaction [18]. The image below explains what questions and information are needed from the adolescent at each stage and essentially these help structure the action plan that will be undertaken in order to facilitate behavioral change self-management.

Additional Services[edit | edit source]

Case Study[edit | edit source]

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

References

[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Batch JA, Baur LA. Management and prevention of obesity and its complications in children and adolescents. The Lancet 2015.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Arsenault LN, Xu K, Taveras EM, Hacker KA. Parents' obesity-related behavior and confidence to support behavioral change in their obese child: Data from the STAR study. Academic pediatrics 2014;14(5):456-462.

- ↑ Knafl KA, Deatrick JA, Havill NL. Continued development of the family management style framework. J Fam Nurs 2012 Feb;18(1):11-34.

- ↑ Jang M, Whittemore R. The Family Management Style Framework for Families of Children with Obesity. Journal of Theory Construction &amp;amp; Testing 2015;19(1).

- ↑ De Onis M., Blössner M., &amp;amp; Borghi E. 2010. Global prevalence and trends of overweight and obesity among preschool children. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.2010; 92 (5):1257-1264.

- ↑ Jang M, Whittemore R. The Family Management Style Framework for Families of Children with Obesity. Journal of Theory Construction &amp;amp; Testing 2015;19(1).

- ↑ Spear AB, Barlow ES, Ervin C, Ludqig, SD, Saelens EB, Schetzina EK, Taveras ME. Recommendations for treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity. Paediatrics. 2007;120, (4)

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical activity for everyone: recommendations.[online]. [viewed 2nd November 2015]. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/physical/recommendations/young.htm.

- ↑ Jacob JJ, Isaac R. Behavioral therapy for management of obesity. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2012 Jan;16(1):28-32.

- ↑ Armstrong MJ, Mottershead TA, Ronksley PE, Sigal RJ, Campbell TS, Hemmelgarn BR. Motivational interviewing to improve weight loss in overweight and/or obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev 2011;12:709–23.

- ↑ Wilfley DE, Kass AE, Kolko RP. Counseling and behavior change in pediatric obesity. Pediatr Clin North Am 2011;58(6):1403-1424.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Gourlan M, Sarrazin P, Trouilloud D. Motivational interviewing as a way to promote physical activity in obese adolescents: A randomised-controlled trial using self-determination theory as an explanatory framework. Psychol Health 2013;28(11):1265-1286.

- ↑ EUFIC WEBSITE 2014 Motivating Behaviour Change [online]. [viewed on 4 November 2015] Available at: http://www.eufic.org/article/en/expid/Motivating-behaviour-change/-

- ↑ Rollnick S And Miller WR. Motivational interviewing? In: HEATHER N. and STOCKWELL T. The essential handbook of treatment and prevention of alcohol problems. John Wiley &amp;amp;amp;amp; Sons 2004: 110-112.

- ↑ Morais HCC, Gonzaga NC, Aquino PdS, Araujo TLd. Strategies for self-management support by patients with stroke: integrative review. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP 2015; 49(1):136-143.

- ↑ Unrod M, Smith M, Spring B, DePue J, Redd W, Winkel G. Randomized controlled trial of a computer-based, tailored intervention to increase smoking cessation counseling by primary care physicians. Journal of General Internal Medicine . 2007; 22( 4): 478-484

- ↑ Ockene IS, Hebert JR, Ockene JK, Merriam PA, Hurley TG, Saperia GM. Effect of training and a structured office practice on physician-delivered nutrition counseling: the Worcester-Area Trial for Counseling in Hyperlipidemia . Am J Prev Med. 1996; 12(4): 252-258.

- ↑ Lawn S, Schoo A. Supporting self-management of chronic health conditions: common approaches. Patient Educ Couns 2010;80(2):205-211.

- ↑ Australian Better Health Initiative 2012 The Model. [online] [viewed 15th November 2015]. Available at: http://www.risen.org.au/CDSM/CDSM_Program_5A.as