Family Centred Intervention and Early Diagnosis: Difference between revisions

m (added photo) |

m (added photos) |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

== Early Intervention == | == Early Intervention == | ||

Early intervention services are a federal program that supports and provides resources for families of special needs infants and toddlers 0-3 years old. Children with developmental disabilities are entitled to various services including | Early intervention services are a federal program that supports and provides resources for families of special needs infants and toddlers 0-3 years old. Children with developmental disabilities are entitled to various services including | ||

[[File:ToddlerPhysio.jpg|thumb|early intervention]] | |||

* PT | * PT | ||

* OT | * OT | ||

| Line 90: | Line 90: | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Course Pages]] | |||

[[Category:Physioplus Content]] | |||

[[Category:Cerebral Palsy]] | |||

Revision as of 19:27, 12 November 2021

Original Editor - User Name

Top Contributors - Robin Tacchetti, Robin Leigh Tacchetti, Jess Bell, Kim Jackson, Naomi O'Reilly, Tarina van der Stockt and Ewa Jaraczewska

Early Intervention[edit | edit source]

Early intervention services are a federal program that supports and provides resources for families of special needs infants and toddlers 0-3 years old. Children with developmental disabilities are entitled to various services including

- PT

- OT

- Speech

- Vision

- Nursing

- Assistive Technology

- Special Education

Evaluations and follow up care is provided in the child's least restrictive or natural environment, typically at home or daycare centre.[1] Traditionally, early intervention has worked off an expert model where the therapist created goals and provided follow up care based on the impairment. Any interventions provided by the family was in adjunct to the healthcare provider. The overall care and decision making for the child was in the hands of the therapist. This model is referred to as a rehabilitation model.[2]

Family-Centred Care[edit | edit source]

Over the past decade, there has been a shift from the therapist-driven model to a family education/empowerment model. Research has shown early intervention is more effective when it has the following components:

- Family-centred

- Collaborative effort between family and therapists

- Within the child's natural environment[3]

Family-centred care (FCC) transfers from the role of planning and goal setting from the therapist to the family. The therapist works as a “coach” to help families identify needs, goals and solutions. The FCS model has specific roles for clinicians and families:

Role of Clinicians:

- provide coaching and education to increase knowledge and impart support for parents and caregivers.

- support parents and caregivers to build parental capacity and expertise, prioritizing a positive parent-child relationship

Role of Families:

- Parents’ goals and aspirations must be central to the intervention

- Parent participation is important to support the need for the frequent practice of activities that lead to skilled movement and functional independence[3]

When families are involved in the care and decisions of their child, the family and the child reap better outcomes.[2]Additionally, research has shown the FCC model to have greater parent satisfaction, reduced cost of healthcare, behavioral/emotional support to a child and a faster recovery.[4]

Solution Focused Coaching[edit | edit source]

Traditionally, early intervention was problem-oriented with a focus on identifying impairments in the body. Interventions were targeted at fixing the dysfunction and decisions about care were solely made by the therapist. Contrastly, in solution focused coaching (SFC) the therapist and family work together utilizing the child’s strengths to envision possibilities and seek solutions to meet the family's needs and targeted goals.[5] [3] With SFC, three key factors are important:

- Therapists coach families toward the creation of goals and envisioned future

- Family empowerment is a priority

- Use of infants strengths and abilities versus problems for goal setting[3]

Early Diagnosis and Referral[edit | edit source]

Cerebral Palsy[edit | edit source]

The most common physical disability in childhood is cerebral palsy (CP) and occurs for every 1 in 500 births. CP is caused by brain injury early in development and presents with disorders in posture and movement leading to activity limitation.[6] Traditionally, a diagnosis would be concluded between 12 and 24 months of age when symptoms were evident. New research, however, reveals that signs and symptoms of CP appear and develop before 2 years of age. Using a combination of medical history, neuroimaging and standardized motor and neurological assessments for infants under 2, the risk of cerebral palsy can be now be predicted.[7] Using diagnostic-specific early assessments can lead to referral of services which will strengthen caregiver well-being, prevent secondary complications and optimize infant cognitive and motor plasticity.[8] The tools below are commonly used for infants under 2 to estimate the risk of a cerebral palsy diagnosis.

Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination[edit | edit source]

The Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination (HINE) has shown high sensitivity in detecting CP in infants, (98% in infants under 5 months old, 90% in infants over 5 months old.[7] This free tool with good interobserver reliability is typically utilized on infants between 3 and 24 months. Neurological function is tested with 26 different criteria based on movements, behaviour, cranial nerve function, protective reactions, reflexes and gross and fine motor function. Test results not only identify children at risk but detail the severity and type of motor impairment. Having this specific information allows early intervention to be targeted to the specific neurological sequelae.[6]

Gross Motor Function Classification System[edit | edit source]

The Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) tool classifies children under 2 into 5 distinct levels depending on the movement that is self-initiated accenting mobility, transfers and sitting. These criteria relate to functional limitations for the child versus quality of movement.

Gross Motor Function Classification System – Expanded and Revised (GMFCS – E & R)

- LEVEL I: Infants move in and out of sitting and floor sit with both hands free to manipulate objects. Infants crawl on hands and knees, pull to stand and take steps holding on to furniture. Infants walk between 18 months and 2 years of age without the need for any assistive mobility device.

- LEVEL II: Infants maintain floor sitting but may need to use their hands for support to maintain balance. Infants creep on their stomach or crawl on hands and knees. Infants may pull to stand and take steps holding on to furniture.

- LEVEL III: Infants maintain floor sitting when the low back is supported. Infants roll and creep forward on their stomachs.

- LEVEL IV: Infants have head control but trunk support is required for floor sitting. Infants can roll to supine and may roll to prone.

- LEVEL V: Physical impairments limit voluntary control of movement. Infants are unable to maintain antigravity head and trunk postures in prone and sitting. Infants require adult assistance to roll.

*** Less favorable outcomes are noted in low and middle income countries with over 73% of children classified as GMFCS level of III-IV.[10]

The Prechtl General Movement Assessment[edit | edit source]

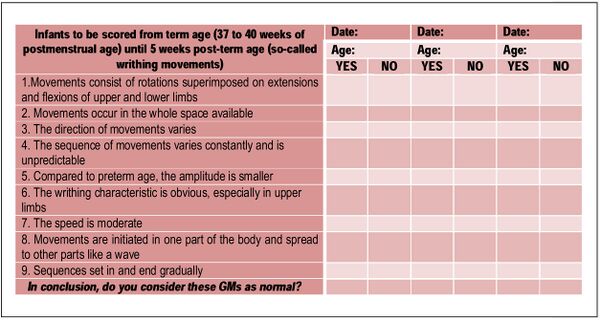

The Prechtl General Movement Assessment is a general movement tool where clinicians watch a short video of a supine infant. Quality and type of movements are classified as “normal” or “abnormal” for 26 items. Based on the score from this test, the presence, type and severity of CP can be predicted. This tool is reliable and quick, but does require training.[3]

Resources[edit | edit source]

- https://www.canchild.ca/en/research-in-practice/family-centred-service

- Gross Motor Function Classification System - Expanded and Revised (GMFCS-ER)

- https://www.physio-pedia.com/Early_Intervention_and_the_Importance_of_Early_Identification_of_Cerebral_Palsy?utm_source=physiopedia&utm_medium=search&utm_campaign=ongoing_internal

- https://www.physio-pedia.com/Early_Intervention_in_Cerebral_Palsy?utm_source=physiopedia&utm_medium=search&utm_campaign=ongoing_internal

- https://www.physio-pedia.com/Cerebral_Palsy_Introduction?utm_source=physiopedia&utm_medium=search&utm_campaign=ongoing_internal

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Tomasello NM, Manning AR, Dulmus CN. Family-centered early intervention for infants and toddlers with disabilities. Journal of Family Social Work. 2010 Mar 24;13(2):163-72.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Dalmau M, Balcells-Balcells A, Giné C, Cañadas M, Casas O, Salat Y, Farré V, Calaf N. How to implement the family-centered model in early intervention. Anales de psicología. 2017;33(3):641-51.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Versfeld, P. Family-Centred Intervention and Early Diagnosis Course. Physioplus, 2021.

- ↑ Raghupathy MK, Rao BK, Nayak SR, Spittle AJ, Parsekar SS. Effect of family-centered care interventions on motor and neurobehavior development of very preterm infants: a protocol for systematic review. Systematic reviews. 2021 Dec;10(1):1-8.

- ↑ Baldwin P, King G, Evans J, McDougall S, Tucker MA, Servais M. Solution-focused coaching in pediatric rehabilitation: an integrated model for practice. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 2013 Nov 1;33(4):467-83

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Romeo DM, Ricci D, Brogna C, Mercuri E. Use of the Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination in infants with cerebral palsy: a critical review of the literature. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2016 Mar;58(3):240-5.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Novak I, Morgan C, Adde L, Blackman J, Boyd RN, Brunstrom-Hernandez J, Cioni G, Damiano D, Darrah J, Eliasson AC, De Vries LS. Early, accurate diagnosis and early intervention in cerebral palsy: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA pediatrics. 2017 Sep 1;171(9):897-907.

- ↑ Early, Accurate Diagnosis and Early Intervention in Cerebral Palsy: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. J Novak et al (2017). AMA pediatrics, 2017 171(9), 897–907.

- ↑ De Sanctis R, Coratti G, Pasternak A, Montes J, Pane M, Mazzone ES, Young SD, Salazar R, Quigley J, Pera MC, Antonaci L. Developmental milestones in type I spinal muscular atrophy. Neuromuscular Disorders. 2016 Nov 1;26(11):754-9.

- ↑ Jahan I, Muhit M, Hardianto D, Laryea F, Chhetri AB, Smithers‐Sheedy H, McIntyre S, Badawi N, Khandaker G. Epidemiology of cerebral palsy in low‐and middle‐income countries: preliminary findings from an international multi‐centre cerebral palsy register. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2021 May 24.

- ↑ Aizawa CY, Einspieler C, Genovesi FF, Ibidi SM, Hasue RH. The general movement checklist: A guide to the assessment of general movements during preterm and term age. Jornal de Pediatria. 2021 Aug 18;97:445-52.