Effective Communication Techniques: Difference between revisions

Robyn Holton (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Robyn Holton (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 75: | Line 75: | ||

Talk may be therapeutic, meaning, a physiotherapist who validates the patients perspective or expresses empathy may help a patient experience improved psychological well being. Leading to the patient experiencing fewer negative emotions (e.g. fear and anxiety) and more positive ones (e.g., hope, optimism and self-worth). | Talk may be therapeutic, meaning, a physiotherapist who validates the patients perspective or expresses empathy may help a patient experience improved psychological well being. Leading to the patient experiencing fewer negative emotions (e.g. fear and anxiety) and more positive ones (e.g., hope, optimism and self-worth). | ||

<br>Non-verbal behaviours such as touch or tone of voice may directly enhance well-being by lessening anxiety or providing comfort<ref name="Henricson et al.">HENRICSON, M., ERSSION, A, MAATTA, S., SERGESTEN, K. and BERGLUND, A.L., 2008. The outcome of tactile touch on stress perameters in intensive care: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. vol. 14, pp. 244-254.</ref><ref name="Knowlton and Larkin">KNOWLTON, G.E. and LARKIN, K.T., 2006. The influence of voice volume, pitch and speech rate on progressive relaxation training: application of methods from speech pathology and audiology. Applied Psychophysiology Biofeedback. vol. 31, pp.173-185.</ref><ref name="Weze et al.">WEZE, C., LETHARD, H.L., GRANGE, J., TIPLADY, P. and STEVENS, G., 2004. Evaluation of healing by gentle touch in 35 clients with cancer. Europe Journal of Oncology Nursing. vol. 8, pp. 40-49.</ref> | <br>Non-verbal behaviours such as touch or tone of voice may directly enhance well-being by lessening anxiety or providing comfort<ref name="Henricson et al.">HENRICSON, M., ERSSION, A, MAATTA, S., SERGESTEN, K. and BERGLUND, A.L., 2008. The outcome of tactile touch on stress perameters in intensive care: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. vol. 14, pp. 244-254.</ref><ref name="Knowlton and Larkin">KNOWLTON, G.E. and LARKIN, K.T., 2006. The influence of voice volume, pitch and speech rate on progressive relaxation training: application of methods from speech pathology and audiology. Applied Psychophysiology Biofeedback. vol. 31, pp.173-185.</ref><ref name="Weze et al.">WEZE, C., LETHARD, H.L., GRANGE, J., TIPLADY, P. and STEVENS, G., 2004. Evaluation of healing by gentle touch in 35 clients with cancer. Europe Journal of Oncology Nursing. vol. 8, pp. 40-49.</ref> | ||

==== Indirect Pathways ==== | ==== Indirect Pathways ==== | ||

Revision as of 00:36, 26 November 2014

Original Editor - Your name will be added here if you created the original content for this page.

Top Contributors - Elaine McDermott, Frank Ryan, Robyn Holton, Shawn Swartz, Kim Jackson, Lauren Lopez, Admin, Zeeshan Hussain Mundh, 127.0.0.1, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Noel McLoughlin, Rucha Gadgil, Aimee Tow and Jess Bell

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Resource Aims[edit | edit source]

Effective Communication Techniques in a healthcare setting has been developed on the bases that physiotherapists are in a unique position as part of a multidisciplinary team in that they can have substantially more contact time with patients than other members of the team. This means the physiotherapist is more appropriately positioned to develop a deeper patient-therapist relationship and in doing so educate and empower the patient of their physical condition and management.

Communication is an important tool in a healthcare setting that when used effectively can educate, empower and de-threaten common health issues patients present with in practice. However, if it is used ineffectively it can have detrimental effects creating fear, confusion and anxiety in patients as well as encouraging resistance to lifestyle changes and healthy behaviours.

It can be overwhelming for newly qualified or student physiotherapists as they must deal with such a broad range of conditions as well as differences in patient personalities, beliefs and motivation. This resource pack uses specific physical conditions as examples, however the communication strategies can be adapted and applied effectively across the broad range of physical conditions dealt with by physiotherapists.

This resource tool is in no way comprehensive and does not aim to cover every physical and mental condition dealt with by physiotherapists. For this reason, this tool is limited to communication around physical conditions and does not include information on communicating with mental issues or learning problems. It is a guide with suggested examples which can be adapted and applied to different situations with regards explaining and treating physical conditions. Included are further readings, reflection sections and relevant continuous professional development recommended to encourage the reader to actively engage with and consolidate their learning.

Audience[edit | edit source]

The Resource is aimed at student/ recently qualified physiotherapists. However, this should not be exclusive as other healthcare professionals, academics or individuals with an interest in the topic may extract relevant and useful information.

Learning Outcomes[edit | edit source]

- Understand the importance of effective communication and identify pathways which communication may be influenced.

- Identify the patients positive and negative emotional triggers and evaluate the impact on physical presentation

- Analyse the prevailing language/metaphors that exist within healthcare and assess their impact on the bio-psyco-social model of pain.

- Understand how assessment and explanation of disorders/pain needs to vary for different patients and select an appropriate communication technique with which to carry this out.

- Identify effective communication methods that may be helpful when explaining a diagnosis/treatment to a patient.

- Reflect upon one's own practice of communication techniques and identify areas requiring improvement

Importance of Good Communication[edit | edit source]

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Communication is an interactive process which involves the constructing and sharing of information, ideas and meaning through the use of a common system of symbols, signs and behaviours[1]. It includes the sharing of information, advice and ideas with a range of people, using;

•verbal

•non-verbal

•written

•e-based

These can be modified to meet the patients preferences and needs.

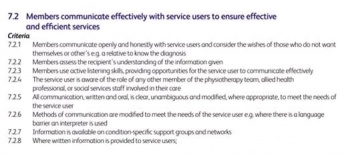

Figure 1: HCPC standards of proficiency (2013).

[[Image:Standards.jpg|border|center|400x300

Skilled and appropriate communication is the foundation of effective practice and is a key professional competence (See HCPC: Standards of Proficiency[2] figure 1 and CSP: quality assurance standards[1] figure 2 above) which is highly valued by physiotherapy recipients[3]. Effective communication requires consideration of the context, the nature of the information to be communicated and engagement with technology, particularly the effective and efficient use of Information and Communication Technology.

Numerous studies have confirmed the importance of communication between physiotherapist and patient and interventions to enhance practice - some of which will be discussed throughout this learning resource.

Communication Pathways to improve health outcomes[edit | edit source]

To understand why communication may lead to better improved health outcomes researchers have identified pathways through which communication influences health and well being and can be simplified in figure 1.3 as proposed by Street[4].

Direct Pathways[edit | edit source]

Talk may be therapeutic, meaning, a physiotherapist who validates the patients perspective or expresses empathy may help a patient experience improved psychological well being. Leading to the patient experiencing fewer negative emotions (e.g. fear and anxiety) and more positive ones (e.g., hope, optimism and self-worth).

Non-verbal behaviours such as touch or tone of voice may directly enhance well-being by lessening anxiety or providing comfort[5][6][7]

Indirect Pathways[edit | edit source]

In most cases, communication affects health through a more indirect or mediated route through proximal outcomes of the interaction, such as;

- satisfaction with care

- motivation to adhere

- trust in the clinician and system

- self efficacy in self care

- clinician – patient agreement

- shared understanding

This could affect health or that could contribute to the intermediate outcomes (e.g., adherence, self-management skills, social support that lead to better health (see Figure 2)[8]. A physiotherapists clear explanation and expression of support could lead to greater patient trust and understanding of treatment options[4]. This in turn may facilitate patient adherence to recommended therapy, which in turn improves the particular health outcome. Increased patient participation in the consultation could help the physiotherapist better understand the patient’s needs and preferences as well as discover possible misconceptions the patient may have about treatment options[4]. The physiotherapist can then have the opportunity to communicate risk information in a way that the patient understands. This could lead to mutually agreed upon, higher quality decisions that best match the patients circumstances[4].

An article by Street et al.[4] explores these pathways to further broaden your knowledge. A link to this article can be found in ‘Further Reading’ section below.

Further Reading[edit | edit source]

|

Street, R.L., Makoul, G., Arora, N.K. and Epstein, R.M. (2009). How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinicial-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient and Education Counselling, 74, pp. 295-301. <span class="Apple-style-span" style="line-height: 19px; " /> Parry, R.H. and Brown, K. (2009). Teaching and learning communication skills in physiotherapy: What is done and how should it be done? Physiotherapy, 95, pp. 294-301. |

Communication during Examination and Assessment[edit | edit source]

How Communication can impact the patient[edit | edit source]

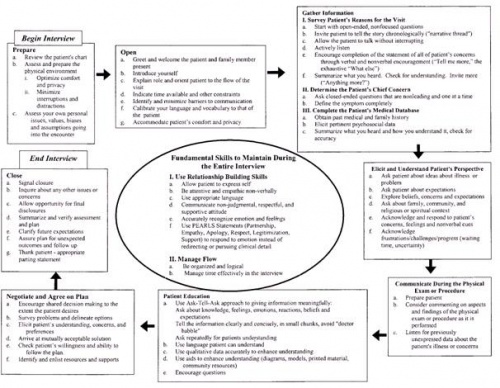

The Macey Model of Doctor-patient Communication is a communication skills model that illustrates fundamental processes applicable to every meeting between physician and patient, and represents a complete set of core skills (see fig. 3.4)[9].

Although this tool was developed for doctors, the model provides an overall framework for systematically teaching vital communication elements[9].

The medical interview, particularly the subjective assessment, will determine the quantity, quality and accuracy of data that the physiotherapist will elicit. In turn, this will affect both the approach to the problem and the consequent care of the patient[9]. Ensuring that we communicate effectively will directly influence the patients behaviour and well being for:

- Satisfaction with care[10]

- Adherence to treatment plans[10]

- Recall and understanding of the information given[10]

- Coping with the diagnosis[10]

- Quality of life and even state of health[10]

Figure 3: The Macey Model of Doctor-patient Communication

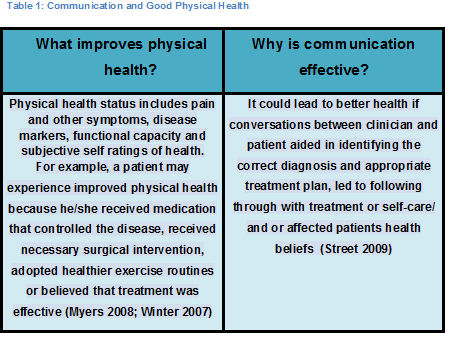

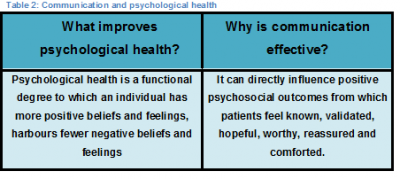

Table 3.1 briefly describes how communication may influence physical and psychological health of the patient.

Patient Learning Styles[edit | edit source]

Miscommunication between patients and physiotherapists is often documented when it comes to diagnosis explanation and treatment advice [11] [12] . Patients will describe symptoms in “lay” terms while physiotherapists often return feedback based on biomedical symptoms and processes of the condition using medical terms without taking into account the gap in the level of knowledge on the subject between the patient and themselves[11] [12]. Research believes that this may be because physiotherapist’s often forget to take into account the difference in literacy levels between themselves and their patient, or they don’t know how to describe a condition outside of the medical model they have been taught during training.[13] .

Studies show that literacy levels in some countries can be as low as age 10, [14]. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development,[15] the UK is now ranked 22nd in a study of 24 EU countries in terms of literacy with a national literacy age of 10 years old.

In addition to this English is not everyone’s first language. According to the 2011 UK census 92% of residents acknowledged English as their first language and of the 8% remaining (3.3 million people), only 79% claimed they could speak English well or very well [16]

Both of these factors may cause difficulty and confusion when trying to speak to a patient about their diagnosis and to make an informed decision around treatment options

What is Learning[edit | edit source]

By getting a better understanding of patient’s learning styles and acknowledging the difference between lay and medical terminology, we can provide effective education which, in return, may increase the compliance and cooperation of patients[12].

Before educating the patient it is crucial that the following aspects are assessed:

- Patients needs

- Patients concerns

- Patients motivation and readiness to learn

- Patients preferences

- Patients support network

- Patients barriers and limitations to learning (mental health status, learning difficulties)

[17]

Patient behaviour is determined by several factors such as family and work commitments[17] . Patients will often weigh up these factors and consider various options before settling on the choice most suitable to their personality and lifestyle [17].

Learning is defined as a process in which knowledge is created through the transformation of experience [18] [19]. Individuals use learning to manage and adapt to everyday situations, giving rise to different types of learning styles[18] [19] .Through various research and studies, learning styles have been organised and categorized into levels, suggesting an individual’s capacity for flexible and adaptive model learning [18] [19]. These levels are ranked in descending order of stability and are listed as:

- Personality traits

- Information processing

- Social interaction

- Instructional preference

[18] [19]

For instructional preference. Patterson (2003) [20]put together the below table which identifies three types of learning styles: Visual, Auditory & Kinesthetic .

The most common learning theory model in application is Kolb’s four stages of experiential model (1984)[21], which, as the names suggest is based around four stages. The ideology is that individual’s transition from phase to phase in their learning process[18] [19]. Very little research is available on the application of these teaching models to a healthcare setting perspective.

Figure 3: Kolb’s four stages of experiential model.

- Concrete experience: The patient learns of their diagnosis for the first time from the physio or they could have some previous knowledge or experience of the condition, possibly from news articles or friends or family members with experience or knowledge of the condition. This stage helps the patient to grasp what their diagnosis and prognosis is.

- Reflection on experience: The patient will go away and review and reflect on the experience and their understanding of their diagnosis.

- Abstract conceptualisation: The patient learns from the experience of their treatment and diagnosis.

- Experimental experience: The patient will plan and adapt to the arising situation and try out what has been learned in terms of education and treatment.

[22]

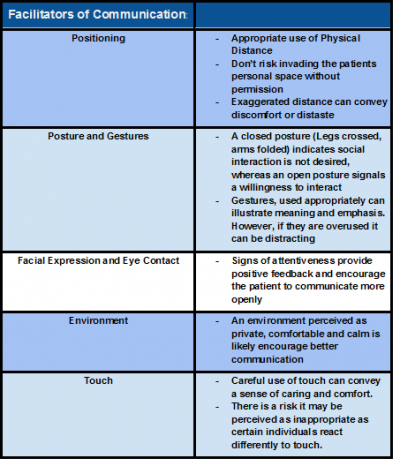

Facilitators of Communication[edit | edit source]

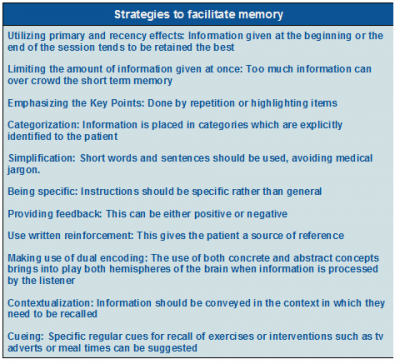

Strategies to Aid Information Recall[edit | edit source]

An important feature of effective communication is the ability of the patients to retain the information that is imparted[23]. Extensive research has been conducted within health care on factors which may hinder or facilitate memory and therefore, the degree of adherence. The following table summarizes some techniques which can help maximise the information patients retain and recall. However, it is important to stress that these techniques should not be seen as a substitute for interpersonal skills and attitude that helps to create a good relationship with the patient, as this is a prerequisite for good communication[23].

Explaining Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Breaking "Bad" News[edit | edit source]

Use of Metaphors in explaining diagnosis[edit | edit source]

“The medical profession has for a long time largely neglected the influence that language itself has in shaping and conceptualising medical practice” (Loftus 2011)

Why is this? Over the past 3 decades there has been a growing body of evidence that has looked at the role of metaphors in healthcare(Loftus 2011). Historically metaphors were thought of being misleading and potentially counter productive for cognitive reconceptualising(Sontag 1978). Contemporary literature is much more welcoming of metaphors, especially within pain management. Now the research debate has shifted toward how metaphors should be applied in clinical practice rather than if metaphors are true or not. (Loftus 2011; & Stewart 2014)

We know that each and every patient that is seen comes with a very individual set of life experiences and different ways of shaping understanding of their “impairments" (Loftus 2011). Language and more specifically metaphors can aid in this process to promote advancement of a more meaningful understanding of diagnoses, avoidance of persistent pain, and self management strategies.(Loftus 2011;Bedell et al. 2004)) Despite these potential benefits, physiotherapists need to be aware of the chance of misinterpretations some patients might take from these metaphors.

In the busy environment of clinical practice(rephrase), physiotherapists can’t loose sight of the real people at the heart of the healthcare system(Stewart 2014). Due to the often complex idiosyncratic nature of bio-psycho-social pain, physiotherapists often use metaphors to try and create an “unique” reconceptualisation of what is really going on with the patients body.( Sullivan, 1995)

If we examine metaphors separate from the healthcare environment we know that metaphors can facilitate new ways of visualising the world and how we act within it. As a child we are always using our imagination or past experiences to create meaning of new experiences we face on a everyday basis. Physiotherapists must aid the patient to find meaning in the dialogue of personal, cultural, and physical experiences that have made up their lives(Gifford 1997).

Now if we integrate pain for example into this situation we can argue that pain is essentially an interpretation by that individual, it can be said that the only way to adequately understand pain is through metaphor itself(Stewart 2014). Ideally a set of metaphors that address the neurobiological contexts as well as the sociocultural contexts of their lives without looking at them dualistically but instead cohesively(Loftus 2011).

Commonly used Metaphors in practice[edit | edit source]

Over the years the use of metaphors have been looked at by many different research papers and some that are continually being used in practice produce poor patient outcomes. Below we will look at a few of the common metaphors being used across healthcare and analyse how they may benefit or be harmful to the patient.

The Body is a Machine [edit | edit source]

- This often implies that the patients are handing over their bodies to a health professional to locate the damage and administer treatment to repair the damage. Much like a car garage.

- Encourages us to think in a Dualistic way (BIOMEDICAL VS. BIO-PSYCHO-SOCIAL) , although if we recognise that social interaction, self interpretation and meaning are important; we must look for more adequate metaphors.

(Loftus 2011)

Medicine is War/ Military Metaphors [edit | edit source]

- Can imply that the patients are being passive and the doctors are warriors.

- Allows patients and clinicians to think that the patient has failed rather than the treatment.

- These metaphors can also lead some clinicians to think of themselves as a poor “soldier” and decrease confidence.

- Military metaphors can direct pain reconceptualisation away from bio-psycho-social evidence and think the war can be won with biomedical means of treatment.

(Loftus 2011;Louw 2011;Stewart 2014)

Brain as a Computer [edit | edit source]

This metaphor can sometimes help patients understand some of the complexities of neurobiology, but downplays the idiosyncratic and adaptive properties of the CNS.

(Stewart 2014)

Journey Metaphor [edit | edit source]

- Some other metaphors paint a more adequate picture for patients and have been successful in practice, especially for patients with consistent pain.

- Contrary to military metaphors, journey metaphors have destinations but in journeys there isn’t just one way to get to that destination. Patients and clinicians have the ability to adjust and try out different avenues. It has been proposed by Reisfield & Wilson (2004) that journey metaphors offer “different roads to travel, various avenues to explore and always there are exits to take.”

- Journey metaphors rightfully shift the focus away from failure or success and focus on personalised adaptive exploration (Hartley 2012).

Advice and Cautions[edit | edit source]

As mentioned before there should be certain caution’s and encouraging tips to think about when delivering metaphors in clinical practice.

“When should we use and not use metaphors?”

Well that all depends on who is seeking medical help and how the metaphors are going to be used. There isn’t one metaphor that is good or bad, one metaphor might work great with one patient and be harmful or insignificant to another patient (Loftus 2011). This is when clinicians must open our toolkit and take out their clinical appraisal skills. Therapists must look at

“What patient has the condition, not what condition does the patient have?”

Physiotherapists must be aware of the potential of imposing our own bias on our patients, this is precisely why communication should be looked at in a dialogical manner.(Stewart 2014 & Loftus 2011)

“It takes two to tango”.

Through a dialogical approach to assessment we can better understand our patients and through that subjective information co-construct more meaningful metaphors (Loftus 2011). “Thacker & Mosley have argued that clinician dominant questioning can negate the critical need for the patients to have their psychological, social and philosophical stories heard.”( Yelling 2011)

Its important that we as clinicians understand and appreciate both the power and subtlety that language can possess (Loftus 2011). The debate shouldn’t be looking at what metaphor is the truest in all senses, this is irrelevant because metaphors aren’t true or false they are useful or not in various contexts.(Loftus 2011).

Communication when addressing persistent pain complaints[edit | edit source]

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Acute pain conditions have a very good rate of healing, but health care systems still find that a large portion of these patients go on to experience persistent pain and maladaptive behaviours (Darlow et al. 2013 & Croft et al. 1998). As a result Persistent Pain conditions place a huge strain on the healthcare system and economy (Darlow et al. 2013). Modern pain research tells us that often patient beliefs play a huge role in the transition from acute pain to chronicity. By better understanding patient beliefs and positively influencing them with reassurance and compassion we can better manage patients perception of pain ( Darlow et al. 2013; Butler & Moseley 2003).

We know from nursing literature that pain is the most common reason for an individual to seek medical advice (Nair & Peate 2012). At times Healthcare Professionals can negatively impact patients beliefs about pain. It is common that some patients feel that their stories haven’t been listened to and consequently their pain is not validated (Yelland 2011).

What is Pain?[edit | edit source]

Every Chronic Pain was once Acute[edit | edit source]

Neuroscience Education[edit | edit source]

According to Adrian Louw (2011) Neuroscience education is a cognitive based intervention that aims at reducing pain and maladaptive behaviours by guiding patients to grasp understanding of the mechanisms underpinning their pain experience..

This semi complex information needs to be delivered to the patient in a way that is clear and easy to understand. Language and other communication techniques such as drawings,pictures, videos, workbooks can aid patient learning. Research shows that traditionally clinicians tend to underestimate patients ability to understand complex pain, when in fact patients are very interested in learning about their pain (Louw 2011 & Moseley 2003).

Multiple studies have shown that Neuroscience Education combined with graded exercise is in line with the best evidence available for treating persistent pain(Louw 2011). Resulting in decreased fear, pain, cognition and physical performance, increased pain thresholds during exercises, and reduced brain activity(especially amygdala) that is usually involved with pain.(Louw 2011 & Veinante et al. 2013)

Explaining Pain: How to do it in under 10 minutes[edit | edit source]

Clinical Example: Osteoarthritis[edit | edit source]

When explaining a condition such as osteoarthritis to a patient we must consider what their viewpoint of the condition must be. Osteoarthritis is a condition of cartilage degeneration, subchondral bone stiffening and active new bone formation (Heuts et al, 2004).

Osteoarthritis is a complex sensory and emotional experience. An individual’s psychological characteristics and immediate psychological contest in which pain is experienced both influence their perception of pain (Hunter 2008).

Research has utilised qualitative methods and focus groups to establish the patient’s point of view. A common theme that is emerging is that patients are sometimes dissatisfied with the overall level of understanding, help and information that is given to them by healthcare professionals (Hill et al 2011). Patients also expressed concern that there was a lack of understanding by healthcare professionals as to the impact that osteoarthritis can have on an individual’s life (Hill et al 2011).

As physiotherapists, we must be aware of current and alternative treatments for OA (hydrotherapy, acupuncture etc) as contradictory information being given to the patient from different sources may lead to confusion as to what exactly they should be doing (Hill et al 2011).

Somers et al (2009) highlights that patients may adopt certain attitudes towards pain; Patients who are pain catastrophizing tend to focus on and magnify their pain sensations. This group of patients tend to feel helpless in the face of pain. Patients who adopt this stance report higher levels of pain, have higher levels of psychological and physical disability.

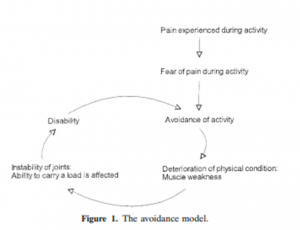

The second stance is patients who have pain related fear. They have a fear of physical activity as a result of feeling vulnerable to pain during activity. This group are more likely to engage in avoidance behaviours such as avoiding movement (Somers et al, 2009)

We as physiotherapists must remember that OA patients with a fear of engaging in painful movements may be hesitant to engage in physical activity. This can contribute to a vicious cycle of a more restricted and a physically inactive lifestyle which will lead to increased pain and disability (Somers et al 2009).

Hendry et al (2006) conducted qualitative research on primary care patients with OA. They found that personal experience, aetiology of arthritis and motivational factors all influenced compliance rates towards physical activity. Some patients believed that their joint problems were a direct result of heavy physical activity (Hill et al 2011). This is where we as clinicians must be aware that patients may present questions such as;

‘why should we exercise when our knees hurt?’

In the same study patients were asking

‘if it is wear and tear on the bone, is it helping to do all this exercise, walking and that?’

As physiotherapists we must be careful with our choice of words, phrases such as ‘wear and tear’ may be misinterpreted by some patients and lead to further maladaptive behaviour. Grive et al (2010) established that an ongoing concern of musculoskeletal professionals is that the use of this ‘wear and tear’ explanation often leads to decreased physical activity to avoid further ‘wearing of the joint’.

A unique approach adopted by a number of patients in the same study by Grive et al (2010) was the ‘use it or lose it’ approach. This simply put was use the joint or lose your functional ability. As physiotherapists we could utilise a similar approach to get our patients to comply with the physical exercise that we have prescribed as an intervention. Through effective communication we can increase a patient’s self efficacy and reduce their level of physical disability (Hunter 2008). Patients with higher self efficacy for pain control had higher thresholds for pain stimuli (Hunter 2008). Can we as physiotherapists use this to our advantage to increase patient’s compliance to exercise?

Exercise has been shown to have a positive effect on functional ability in patients with OA (Heuts et al, 2004). We as physiotherapists must consider the role of pain related fear in patients with OA and investigate different treatment approaches to combat this behaviour (Heuts et al, 2004).

Scopaz et al (2009) suggests psychological factors such as anxiety, fear and depression may also be related to physical function in patients with OA of the knee.

Further to this, a model of fear avoidance suggests that patients can either be adaptive and non-adaptive in their approach to their pain and functional ability (Scopaz et al, 2009).

This model indicates that anxiety + fear avoidance beliefs are significant predictors of self report physical function in patients with knee OA (Scopaz et al, 2009).

Following on from this, we may also consider the avoidance model presented by Dekker et al (1993)

This model indicates that a decreased muscle strength as a result of activity avoidance leads to activity limitations (Holla et al, 2012).

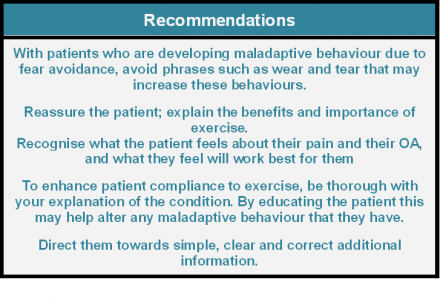

Recommendations[edit | edit source]

'What can us as physiotherapists do to combat these beliefs that may be instilled in patients?'

Table 7 highlights some useful techniques when managing patients with OA.

Sensitive Issues: Obesity[edit | edit source]

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Primary care providers and particularly physiotherapists are being encouraged to provide a more active approach in the management of obesity (Stafford et al. 2002). However physiotherapists have encountered many challenges related to addressing obesity with patients (Alexander et al. 2007). Given that obesity is becoming an epidemic in many nations throughout the world, the need to understand how, when and with whom to have these discussions which becomes essential in order to provide effective care for obese patients. There is a growing need for the training of physiotherapists in areas such as weight loss counseling in order to reduce the barriers encountered when discussing obesity (Alexander et al. 2007).

Wadden & Didie (2003) reported that patients observed the terms obesity and fatness to be very undesirable descriptors used by their physicians when discussing their body weight. Other terms such as large size, heaviness and excess fat were also highlighted as undesirable. The use of these terms by physicians can be interpreted as offensive or hurtful by the patient and lead to a breakdown in communication.

The study reported that weight was the most favourably rated term to be used by physicians as it is easily understood and non judgemental. Another term which was viewed as favourably, as it was non judgemental was BMI, however it is found to be not universally known.

Johnson (2002) reported that some patients preferred to be described as plus sized, large or even fat. By embracing these terms these patients are motivated to remove the negativity and stigma related to them.

Wadden and Didie (2003) reported the most beneficial approach would be to ask the patient how they feel and their thoughts towards their weight. Using this approach the physiotherapist should seek the patients consent and come to an agreement to address and discuss the issue. Caution should be taken to avoid reiterating the hazards obesity has to the patients health. Wadden et al, 2000 reported obese patients often experience a feeling that care providers seldom understand how much they suffer with their weight issues. Utilising the conversation approach also allows the physiotherapist to show respect and empathy to the patient by focusing on the positive steps they may have taken previously to tackle the issue.

The issue with "Calling it as it is"[edit | edit source]

This approach fails to avoid the degrading and offensive terms, used by the public, and causes more negative effects than beneficial effects (Johnson 2002). It is a challenge for obese individuals to understand the medical implication of these terms as they cannot separate them from the degrading aspects of the terms used by the public.Using a confrontational approach instead of a discussion with the patient is far more likely to negatively affect the patient’s moral, feelings and confidence. Johnson (2002) reports that care providers who approach the issue by attempting to 'break through the patient’s denial' of their weight issues, are more likely abolishing the patients trust and their motivation to return for future sessions and care. This is the most common outcome when individuals are advised to battle their obesity by losing weight, to avoid the ominous medical consequences.

More desirable and beneficial outcomes can be achieved through the use of motivational interviewing and discussions with patients in need of weight management compared to a confrontational approach (Miller & Rollnick 2002; Wadden & Diddie 2003)

Motivational Interviewing[edit | edit source]

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Evidence has shown that patient-centred approaches to health care consultations are more effective than the traditional advice giving, especially when lifestyle and behaviour change are part of the treatment (Britt et al. 2004).

In the past, healthcare practitioners encouraged patients to change their lifestyle habits through provision of direct advice about behaviour change (Rollnick et al. 2010). However, this has proven to be unsuccessful, as evidence show success rates of only 5-10% (Rollnick et al. 1993). Additionally, this can put a strain on the patient-therapist relationship with the patient perceiving this style as being lectured on their lifestyle choices (Stott & Pill 1990).

Patients can also feel that the therapist is not considering the personal implications the change may have on their life, as they are just placing emphasis on the future benefits and not recognising the initial struggle the patient may have to go through (Britt et al 2004). Such an encounter can risk the patient becoming resistant to change or further increasing their resistance to change (Miller & Rollnick 1991). This resistance to change was seen as a personality trait that could only be dealt with by direct confrontation which potentially placed a further strain on the patient-therapist relationship (Miller 1994).

Research has shown that patient-centred approaches have better outcomes in terms of patient involvement and compliance (Biritt et al 2004, Ockene et al. 1991). The key feature to these approaches is that the patient actively engages in discussing a solution for their problem (Emmons & Rollnick 2001).

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is based off Miller & Rollnick’s (1991) experience with treatment for problem drinkers and is becoming increasingly popular in healthcare settings. The model views motivation as a state of readiness to change rather than a personality trait (Rollnick et al 2008). . As such, motivation can fluctuate over time and between situations. It can also be encouraged to go in a particular direction. By taking this view , a patient’s resistance to change is no longer seen as a trait of the person but rather something that is open to change (Rollnick et al. 2010). Therefore, the main focus of MI is to facilitate behaviour change by helping the patient explore and resolve their ambivalence to the change (Rollnick et al. 2010).

While MI is patient centred and focuses on what the patient wants, thinks and feels, it differs slightly from other patient-centred approaches as it is directive (Biritt et al. 2004). In using MI there is the clear goal of exploring the patient’s resistance to change in such a way that the patient is likely to change their behaviour in the desired direction (Biritt et al. 2004).

The focus of Motivational Interviewing is to

assist the patient in examining their expectations about the consequences of engaging in their behaviour.

Influence their perceptions of their personal control over the behaviour through use of specific techniques and skills.

(Rollnick et al 2008).

A benefit to this approach is that time can be saved by avoiding unproductive discussion by using rapid engagement to focus on the changes that make a difference (Rollnick et al 2010).

Theoretical Bases[edit | edit source]

Motivational Interviewing is not based on any one specific theory as Miller drew from different aspects of social psychology using processes such as attribution, cognitive dissonance, and self efficacy (Britt et al 2004), as well as empathetic processes from Rodgers (1991) . As interest in applying the model to healthcare setting increased, it was further elaborated and developed by Millner & Rollnick (1995)

(Table of models of change MI draws from).

MI has been linked to the transtheoretical model of change, with the model providing the framework with which to understand the change process and MI providing the means of facilitating that change (Sobell et al. 1994).

MI differs from other patient centred approaches as it includes the concept of readiness to change (Rollnick et al. 1993). This concept can help to explain why direct advice-giving alone can be limited in effectiveness. If the patient is not ready to change then the advice is unlikely to be acted upon (Millner & Rollnick 1995). Due to this, behaviour change does not have to be the only goal of the healthcare professional. They can aim to increase a patient’s readiness to change through using MI (Emmons & Rollnick 2001). Using this concept means that interventions can be tailored appropriately to suit the degree of readiness to change of a patient, increase greater parity between the PT and patient agenda (Rollnick et al. 1999). This potentially;

- decreases patient resistance

- increases effectiveness of the intervention and

- strengthens the patient-PT relationship

(Emmons & Rollnick 2001).

(Table describes stages of readiness to change)

The principles of MI are closely related to those of cognitive dissonance (Britt et al 2004). MI focuses on resolving ambivalence by focusing on inconsistencies (Emmons & Rollnick 2001). This is creating dissonance. Techniques used in MI, such as reflection and summarizing, function to develop cognitive dissonance (Millner & Rollnick 2002). It produces as dissonant state by focusing on the ambivalence and then controls the direction chosen for the dissonance resolution through skilful and practiced use if the MI techniques (Britt et al 2004).

Principles of MI[edit | edit source]

MI is based on the following principles (insert image)

An empathetic conversational style is fundamental (Millner & Rollnick 1995). The PT's attitude must be one of acceptance and they must view resistance to change as normal (Rollnick et al 2010). Using this empathetic style the PT can create and amplify any discrepancy between the patients present behaviour and their goals in such a way that the patient can present an argument for change (Britt et al 2004). Argumentation between the patient and PT should be avoided as it is counterproductive and only serves to increase resistance to change and damage the patient PT relationship (Millner & rollnick 1995, Rollnick et al 2008). The consultation is carried out in a facilitative way where the relationship between the PT and patient is seen more as a partnership instead of an expert/client (Rollnick et al 2010). The patient is viewed as a valuable resource to finding a solution to their problem and they are responsible for choosing and carrying out personal change (Rollnick et al 2010, Britt et al 2004). In order for this to be effective the patient must have a belief in themselves and their ability to change (Millner & Rollnick 2002). As such, the PT must encourage, support and build self efficacy (Britt et al 2004, Rollnick et al 2010).

There is one key distinction between Motivational Interviewing and other patient centred approaches. MI is not viewed as a technique which is applied to patients, but rather an interpersonal style which is shaped by guiding principles of what triggers behaviour change processes (Rollnick et al 2010). The spirit of adhering to the method involves allowing patients to express their own arguments to change and the PT to accept these (Emmons & Rollnick 2001). MI is an individually tailored client centred method which changes to suit each individual ensuring that effectiveness is increased (Millner & Rollnick 2002, Rollnick et al 2010). As such, there is no set structure to MI as a too tightly structured model will fail to honour the uniqueness of the individual, their views and their issues (Rollnick et al 2010, Rollnick et al 2008). However there is a range of techniques that can be used interchangeably to effectively carry out MI (Millner & Rollnick 1995).

MI Techniques[edit | edit source]

It is the patient’s task to articulate and resolve their resistance to change (Rollnick et al 2010, Mllner & Rollnick 1995). It is the therapist’s task to expect and recognise resistance and to be directive in helping the patient recognise and resolve this resistance (Rollnick et al 2010). This can be done through the use of MI specific trainable techniques (Millner & Rollnick 1995).

There are 3 elements to the technical aspects of MI

- Client centred counselling skills based on Rogerson counselling

- Reflective Listening statements, directive questions and strategies for eliciting internal motivation from the patient. These are in the form of self motivating statements from the patient as is encourages them to examine their resistance to change and make their own decision about why and how to proceed.

- Strategies for ensuring client resistance are minimized.

(Millner & Rollnick 2002)

Motivational Interviewing has been modified for use in healthcare settings (Rollnick et al 2010). This is mainly to overcome issues surrounding time constraints, as intervention effectiveness increases with contact time (Miller & Rose 2009), yet a general first PT appointment will last 40 minutes. Models have been developed to deliver 30 minute interventions based on a framework. One such framework is Brief Motivational Interviewing (BMI) (Rollnick et al 2010). This is a set menu of techniques which follow the spirit and practice of MI. It has been designed for use in a 40 minute single session in a primary healthcare setting (Rollnick et al 2010).

A very clear distinction is made between the practitioners job, which is providing facts, and the patients role which is the personal interpretation of how those facts apply to them (Miller & Rose 2009, Rollnick et al 2008). This influences the decision making process by actively engaging the client in the evaluation of their lifestyle and behaviour and can potentially promote a change in the balance of positive and negative aspects to change relating to their behaviour (Miller & Rollnick 2002). Traditionally the PT would be seen in the role of an expert and the advice given and the interpretation would be delivered by the PT in one message (Britt et al 2004). With using MI, the patient is in the role of the expert as they must decide how the facts are interpreted and whether it is relevant to their situation (Millner & Rollnick 2002).

The PT uses reflective listening in seeking to further understand the patient’s point of views (Millner & Rollnick 2002). Through expressing acceptance and affirming the patients freedom of choice and self determination, they can monitor and influence the patient’s readiness to change (Rollnick et al 2010). However, care must be taken not to jump ahead of the patient or take over the decision making as this can lead to increased patient resistance (Emmons & Rollnick 2001). Advice must not be given without the patient’s permission and when given, it is always accompanied by encouragement to the patient to make their own choices (Rollnick et al 2010). It is also the patient’s decision as to where to take the consultation (Rollnick et al 2010). The PT should encourage this through use of agenda setting to help structure the discussion so that it is meaningful and important to the patient (Rollnick et al. 2010).

Personal dissonance is a strategy commonly used in motivational interviewing (Rollnick et al 2008). Its aim is to create dissonance between the patient’s positive image of themselves and their negative image of themselves (Britt et al 2004). They are encouraged to outline the positives in remaining how they are, followed by the negatives. The PT should encourage them to talk about specific individualised problems and concerns they have about their own behaviour. The strategy concludes with a summary which highlights both the problems and concerns and the positive benefits as outlined by the patient. Following this the patient can be encouraged to weigh up the pros and con's of behaviour change. The PT can assist with support and influence the patient’s readiness to change through this discussion (Millner & Rollnick 2002).

These strategies are not used in isolation or in a set way (Rollnick et al 2010). All techniques are used alongside each other in a way which is unique to each individual and problem (Rollnick et al 2008). MI should not be thought of as a quick fix method or clever technique used to get patients to do something they do not want to (Britt et al 2004). It is something that is done with and for them (Rollnick et al 2010). If the patient responds positively and becomes active in the change discussion this can be viewed as positive feedback (Rollnick et al 2010). However, resistance is a signal to change strategy (Rollnick et al 2010). The resistance should be acknowledged by the PT and they should encourage the patient to further explore this resistance with a view to shift the patient’s perception (Rollnick et al 2010).

Summary[edit | edit source]

MI involves helping patients to say why and how they might change based on the use of a guiding style. A guiding style is used to engage patients, clarify their strengths and aspirations, evoke their own motivations for change and promote autonomy of decision making.

PT's should practise a guiding rather than a direct style, develop strategies to elicit the patient’s own motivation to change and refine their listening skills and respond by encouraging the patient to participate in change talk.

How to best Implement MI[edit | edit source]

Useful Questions[edit | edit source]

Step 1: Practice using a Guiding Style[edit | edit source]

The PT should take the stance of an informed guide, collaborate with patients, emphasise the patients role in decision making and facilitate their self efficacy and motivation (Millner & Rollnick 2002, Rollnick et al 2010). The PT controls the structure of the consultation and provided information when requested but the patient is responsible for leading the change discussion and providing any solutions to problems (Rollnick et al 2010).

Using 3 core skills, the guiding style can successfully draw out the patients views and ideas:

Asking- open ended questions encourage the patient to consider why and how they might change their behaviour.

Listening to the patients experience- use reflective listening statements or brief summaries. This shows empathy and encourages the patient to elaborate further as well as it being the best way to respond to and understand resistance.

Informing- ask permission from the patient before providing information and then discuss the patients views of the implications of the advice.

(Millner & Rollnick 2002, Britt et al 2004, Rollnick et al 2010)

Step 2: Develop Useful Strategies[edit | edit source]

Agenda Setting: Deciding What to Change[edit | edit source]

Instead of imposing your priority on patients, the PT invites them to select an issue which they feel most ready to tackle (Rollnick et al 2010)

Pro's & Con's: Deciding Why the Change[edit | edit source]

Asking the patient their views on the pro's and cons of keeping their behaviour the same can be helpful in influencing their readiness to change. The next step would be to discuss with them if change was a possibility and how they could bring it about.

(Rollnick et al 2010)

Assess Importance and Confidence[edit | edit source]

For this method to be successful the PT needs to spend their time where it is most needed. Patients who are unconvinced of the benefit of change or their ability to change are less likely to change their behaviour. The following line of questioning has been shown to be successful in MI in helping patients to quit smoking (Rollnick et al 2010)

Exchange Information[edit | edit source]

Miller et al (1988) have shown that the most successful way of exchanging information with the patient is by using the elicit-provide-elicit strategy. This is where the patient clarifies the personal implications of the information which is provided to them by the PT. (Rollnick et al 2010)

Setting Goals[edit | edit source]

Patients should set their own goals, as this will increase motivation to work towards change. Questioning styles such as the following can be used to encourage the patient to come up with practical solutions as well as offering suggestions in a way which will not increase resistance (Rollnick et al 2010)

Step 3: Skillfully respond to and change patients language[edit | edit source]

A PT can further enhance their MI skills by paying attention to the language used by patients (Miller & Rose 2009). Patients either use change talk about how or why they might change (I want to, I should exercise etc.). Or the opposite (I’ve never been able to lose weight etc.). The PT can chose whether to encourage the patient to use change talk or not but studies believe that readiness to change is more likely to be enhanced and the subsequent change is more likely to take place when change talk is used (Miller & Rose 2009).

Challenges faced by PT's when using MI[edit | edit source]

Practise, training, supervision and feedback on performance will increase the PT's ability and confidence in using efficient questioning that suits both their own personality, that of their patient and the setting (Rollnick et al 2010).

The hardest challenge most PT's will face is using the guiding style and empathetic attitude as this requires the PT to ignore the tendency to identify and solve the problems for the patient (Britt et al 2004, Rollnick et al 2008). This can make PT's feel like they do not have control of the session (Rollnick et al 2010), but they can still retain control of the direction of the session while giving the control of the what, why and how to change to the patient (Millner & Rollnick 2002, Rollnick et al 2010). The PT can still offer advice and expertise but in a way that is collaborative with the patient’s views and emphasising that the patient makes the final decision on what they will do (Rollnick et al 2010).

Examples in Practice[edit | edit source]

The videos below show a healthcare professional attempting to embark on a conversation about quitting smoking with a patient. This is a scenario very applicable to physiotherapists, especially those working in a respiratory area. The first video shows the traditional advice giving approach, while the second shows the implementation of motivational interviewing techniques.

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Quality Assurance Standards for Physiotherapy Service Delivery. (2012). Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (CSP).

- ↑ Standards of Proficiency - Physiotherapists. (2013). Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC).

- ↑ PARRY, R.H. and BROWN, K.,2009. Teaching and learning communication skills in physiotherapy: What is done and how should it be done? Physiotherapy. vol.95, pp. 294-301.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 SREET, R.L., MAKOUL, G., ARORA, N.K. and EPSTEIN, R.M., 2009. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinicial-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient and Education Counselling. vol. 74, pp. 295-301.

- ↑ HENRICSON, M., ERSSION, A, MAATTA, S., SERGESTEN, K. and BERGLUND, A.L., 2008. The outcome of tactile touch on stress perameters in intensive care: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. vol. 14, pp. 244-254.

- ↑ KNOWLTON, G.E. and LARKIN, K.T., 2006. The influence of voice volume, pitch and speech rate on progressive relaxation training: application of methods from speech pathology and audiology. Applied Psychophysiology Biofeedback. vol. 31, pp.173-185.

- ↑ WEZE, C., LETHARD, H.L., GRANGE, J., TIPLADY, P. and STEVENS, G., 2004. Evaluation of healing by gentle touch in 35 clients with cancer. Europe Journal of Oncology Nursing. vol. 8, pp. 40-49.

- ↑ STEWART, M.A., 1995. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. Can Med Assoc J. vol. 152, pp. 1423-1233.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 KALET, A., PUGNAIRE, M.P., COLE-KELLY, K., JANICIK, R., FERRARA, E., SCHWARTZ, M.D., LIPKIN, M. and LAZARE, A., 2004. Teaching communication in clinical clerkships: Models from the macey initiative in health communications. Academic Medicine. vol. 79, no. 6, pp. 511-520.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 ONG, L.M., VISSER, M.R., LAMMES, F.B. and de HAES, J.C., 2000. Doctor-patient communication and cancer patients’ quality of life and satisfaction. Patient Education Counselling. vol. 41, pp. 145-156.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 GILL, V. T., &amp;amp;amp;amp; MAYNARD, D. W. (2006). Explaining illness: patients' proposals and physicians' responses. STUDIES IN INTERACTIONAL SOCIOLINGUISTICS, vol. 20, pp 115 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Gill & Maynard" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 DONOVAN, J. (1991). Patient education and the consultation: the importance of lay beliefs. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, vol. 50, Suppl 3, pp. 418.

- ↑ SULLIVAN, R. J., MENAPACE, L. W., &amp;amp;amp; WHITE, R. M. (2001). Truth-telling and patient diagnoses. Journal of medical ethics, vol. 27, issue 3, pp.192-197

- ↑ WEISS BD, REED RL, KLIGMAN EW (1995) Literacy skills and communication methods of low-income older persons. Patient Educ Counsel. Vol .25, pp.109–119

- ↑ ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT, (2012), Education at a glance, available at http://www.keepeek.com/Digital-Asset-Management/oecd/education/education-at-a-glance-2014_eag-2014-en#page1, accessed on 24/11/14

- ↑ OFFICE OF CENTRAL STATISTICS (2011), 2011 Census: Quick Statistics for England and Wales, March 2011, available at http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/census/2011-census/key-statistics-and-quick-statistics-for-wards-and-output-areas-in-england-and-wales/STB-2011-census--quick-statistics-for-england-and-wales--march-2011.html , accessed 24/11/14

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 STRÖMBERG, A. (2005). The crucial role of patient education in heart failure.European Journal of Heart Failure, vol. 7 issue 3, pp. 363-369.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 CASSIDY, S. (2004). Learning styles: An overview of theories, models, and measures. Educational Psychology, vol. 24, issue 4, pp. 419-444.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 HAUER, P., STRAUB, C., &amp;amp;amp;amp; WOLF, S. (2005). Learning styles of allied health students using Kolb's LSI-IIa. Journal of Allied Health, vol. 34 issue 3, pp. 77-182

- ↑ PATTERSON, D. J. (2003). Learning Styles. Journal of Adventist Education Summer, vol. 39.

- ↑ KOLB, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (Vol. 1). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- ↑ SPENCER, J. (2003). Learning and teaching in the clinical environment. Bmj, vol. 326, issue 7389, pp. 591-594.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 SIM, J. 2002. Extract- Categories of Intervention. In: J. PRYOR &amp; S.A. PRASAD. Eds. Physiotherapy for Respiratory and Cardiac problems: Adults and Pediatrics. 3rd edition. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone