Effective Communication Techniques: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(updated categories - removed course pages) Tags: Manual revert Visual edit |

||

| (292 intermediate revisions by 14 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | <div class="editorbox"> | ||

'''Original Editor '''- | '''Original Editor '''- [[User:Robyn Holton|Robyn Holton]], [[User:Frank Ryan|Frank Ryan]], [[User:Shawn Swartz|Shawn Swartz]], [[User:Elaine McDermott|Elaine McDermott]], [[User:Noel McLoughlin|Noel McLoughlin]], [[User:Zeeshan Mundhas|Zeeshan Mundhas]] part of [[Current and Emerging Roles in Physiotherapy Practice|Queen Margaret University's Current and Emerging Roles in Physiotherapy Practice Project]] | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

Effective communication techniques in a healthcare setting have been developed on the basis that physiotherapists are in a unique position as part of a multidisciplinary team in that they can have substantially more contact time with patients than other members of the team. This means the physiotherapist is more appropriately positioned to develop a deeper patient-therapist relationship and in doing so educate and empower the patient of their physical condition and management. | |||

Communication is an important tool in a healthcare setting that when used effectively can educate, empower and de-threaten common health issues patients present within practice. However, if it is used ineffectively it can have detrimental effects creating fear, confusion and anxiety in patients as well as encouraging resistance to lifestyle changes and healthy behaviours. | |||

== Importance of Good Communication == | == Importance of Good Communication == | ||

Communication is an interactive process which involves the constructing and sharing of information, ideas and meaning through the use of a common system of symbols, signs. and behaviours<ref name="CSP" />. It includes the sharing of information, advice, and ideas with a range of people using: | |||

Communication is an interactive process which involves the constructing and sharing of information, ideas and meaning through the use of a common system of symbols, signs and behaviours | |||

* | *Verbal | ||

* | *Non-verbal | ||

* | *Written | ||

* | *E-based | ||

These can be modified to meet the | These can be modified to meet the patient's preferences and needs. | ||

<div class="row"> | |||

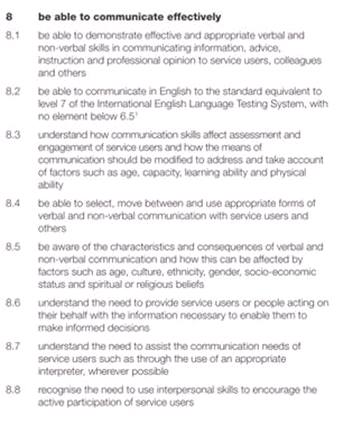

<div class="col-md-6">'''Figure 1 - CSP quality assurance standards (2012)'''<br>[[Image:Standards.jpg]]</div> | |||

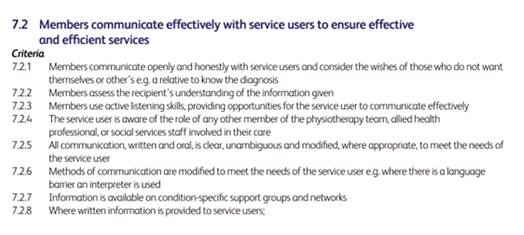

<div class="col-md-6">'''Figure 2 - HCPC standards of proficiency (2013)'''<br>[[Image:HCPC.jpg|border]] </div> | |||

</div> | |||

=== Communication | Skilled and appropriate communication is the foundation of effective practice and is a key professional competence (See CSP: quality assurance standards<ref name="CSP">Quality Assurance Standards for Physiotherapy Service Delivery. (2012). Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (CSP).</ref> and HCPC: Standards of Proficiency<ref name="HCPC">Standards of Proficiency - Physiotherapists. (2013). Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC).</ref> figure 2, above) which is highly valued by physiotherapy recipients<ref name="Parry and Brown">Parry RH, Brown K. Teaching and learning communication skills in physiotherapy: What is done and how should it be done?. Physiotherapy. 2009 Dec 1;95(4):294-301.</ref>. Effective communication requires consideration of the context, the nature of the information to be communicated and engagement with technology, particularly the effective and efficient use of Information and Communication Technology. | ||

== Benefits of Good Communication == | |||

Effective communication does not only improve understanding between health professionals and patients but it can also have a positive impact on health outcomes. To understand why communication may lead to [[Communication to Improve Health Outcomes|improved health outcomes]] researchers have identified direct and indirect pathways through which communication influences health and well being.<ref name="Street et al.">Street Jr RL, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician–patient communication to health outcomes. Patient education and counseling. 2009 Mar 1;74(3):295-301.</ref>.<br> | |||

==== Direct Pathways ==== | |||

Talk may be therapeutic, meaning, a physiotherapist who validates the patients perspective or expresses empathy may help a patient experience improved psychological well being. Leading to the patient experiencing fewer negative emotions (e.g. fear and anxiety) and more positive ones (e.g., hope, optimism and self-worth). | |||

Non-verbal behaviours such as touch or tone of voice may directly enhance well-being by lessening anxiety or providing comfort<ref name="Henricson et al.">Henricson M, Ersson A, Määttä S, Segesten K, Berglund AL. The outcome of tactile touch on stress parameters in intensive care: a randomized controlled trial. Complementary therapies in clinical practice. 2008 Nov 1;14(4):244-54.</ref><ref name="Knowlton and Larkin">Knowlton GE, Larkin KT. The influence of voice volume, pitch, and speech rate on progressive relaxation training: application of methods from speech pathology and audiology. Applied psychophysiology and biofeedback. 2006 Jun 1;31(2):173-85.</ref><ref name="Weze et al.">Weze C, Leathard HL, Grange J, Tiplady P, Stevens G. Evaluation of healing by gentle touch in 35 clients with cancer. European journal of oncology nursing. 2004 Mar 1;8(1):40-9.</ref> | |||

==== Indirect Pathways ==== | ==== Indirect Pathways ==== | ||

In most cases, communication affects health through a more indirect or mediated route through proximal outcomes of the interaction, such as; | In most cases, communication affects health through a more indirect or mediated route through proximal outcomes of the interaction, such as; | ||

*Satisfaction with care | *Satisfaction with care | ||

* | *Motivation to adhere | ||

* | *Trust in the clinician and system | ||

*Self-efficacy in self care | |||

*Clinician - patient agreement | |||

*Shared understanding | |||

* | |||

* | |||

* | |||

This could affect health or that could contribute to the intermediate outcomes (e.g., adherence, self-management skills, social support that lead to better health<ref name="Stewart">Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1995 May 1;152(9):1423.</ref>. | |||

[[ | A physiotherapists clear explanation and expression of support could lead to greater patient trust and understanding of treatment options<ref name="Street et al." />. This in turn may facilitate patient adherence to recommended therapy, which in turn improves the particular health outcome. Increased patient participation in the consultation could help the physiotherapist better understand the patient’s needs and preferences as well as discover possible misconceptions the patient may have about treatment options<ref name="Street et al." />. The physiotherapist can then have the opportunity to communicate risk information in a way that the patient understands. This could lead to mutually agreed upon, higher quality decisions that best match the patients circumstances<ref name="Street et al." />. Key factors of [[Communication to Improve Health Outcomes|communication to improve health outcomes]]: | ||

* Examination and Assessment - using clear concise language and allowing the patient time to talk will influence the quantity, quality and accuracy of data | |||

* Respect Clients individuality and background - adjusting tone and level of language as well as using lay terms rather than medical terms can help improve understanding and make patients feel at ease<ref name="Gill & Maynard">Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1995 May 1;152(9):1423.</ref><ref name="Donovan">Donovan J. Patient education and the consultation: the importance of lay beliefs. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 1991 Jun;50(Suppl 3):418.</ref> | |||

* Respect a patients space - do not invade their space without first asking permission | |||

* Be open and create a relaxed atmosphere | |||

* Be attentive - Look at the patient when they are talking | |||

* Environment - Provide the patient with an area that is private and away from noise and interruptions | |||

<div> | |||

== Communicating Sensitive Issues == | |||

Primary care providers and particularly physiotherapists are often faced with sensitve issues within their daily practice. One example is dealing with obesity and encouraging patients to take a more active approach in the management of obesity<ref name="Stafford et al.2002">Stafford RS, Farhat JH, Misra B, Schoenfeld DA. National patterns of physician activities related to obesity management. Archives of Family Medicine. 2000 Jul 1;9(7):631.</ref>. However physiotherapists have encountered many challenges related to addressing obesity with patients<ref name="Alexander et al 2007" />. Given that obesity is becoming an epidemic in many nations throughout the world, the need to understand how, when and with whom to have these discussions which becomes essential in order to provide effective care for obese patients. There is a growing need for the training of physiotherapists in areas such as weight loss counseling in order to reduce the barriers encountered when discussing obesity <ref name="Alexander et al 2007">Alexander SC, Østbye T, Pollak KI, Gradison M, Bastian LA, Brouwer RJ. Physicians' beliefs about discussing obesity: results from focus groups. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2007 Jul;21(6):498-500.</ref>. | |||

Wadden & Didie<ref name="Wadden and Didie 2003)">Wadden TA, Didie E. What's in a name? Patients’ preferred terms for describing obesity. Obesity Research. 2003 Sep;11(9):1140-6.</ref> reported that patients observed the terms obesity and fatness to be very undesirable descriptors used by their physicians when discussing their body weight. Other terms such as large size, heaviness and excess fat were also highlighted as undesirable. The use of these terms by physicians can be interpreted as offensive or hurtful by the patient and lead to a breakdown in communication.<br>The study reported that weight was the most favourably rated term to be used by physicians as it is easily understood and non judgemental. Another term which was viewed as favourably, as it was non judgemental was BMI, however it is found to be not universally known. | |||

Johnson<ref name="Johnson 2002" /> reported that some patients preferred to be described as plus sized, large or even fat. By embracing these terms these patients are motivated to remove the negativity and stigma related to them.<br>Wadden and Didie<ref name="Wadden and Didie 2003">Wadden TA, Didie E. What's in a name? Patients’ preferred terms for describing obesity. Obesity Research. 2003 Sep;11(9):1140-6.</ref> reported the most beneficial approach would be to ask the patient how they feel and their thoughts towards their weight. Using this approach the physiotherapist should seek the patients consent and come to an agreement to address and discuss the issue. Caution should be taken to avoid reiterating the hazards obesity has to the patients health. Wadden et al<ref name="Wadden et al 2000">Wadden TA, Anderson DA, Foster GD, Bennett A, Steinberg C, Sarwer DB. Obese women's perceptions of their physicians' weight management attitudes and practices. Archives of Family Medicine. 2000 Sep 1;9(9):854.</ref>, reported obese patients often experience a feeling that care providers seldom understand how much they suffer with their weight issues. Utilising the conversation approach also allows the physiotherapist to show respect and empathy to the patient by focusing on the positive steps they may have taken previously to tackle the issue. <br> | |||

=== The Issue With "Calling It As It Is" === | |||

== | This approach fails to avoid the degrading and offensive terms, used by the public, and causes more negative effects than beneficial effects <ref name="Johnson 2002" />. It is a challenge for obese individuals to understand the medical implication of these terms as they cannot separate them from the degrading aspects of the terms used by the public.Using a confrontational approach instead of a discussion with the patient is far more likely to negatively affect the patient’s moral, feelings and confidence. Johnson<ref name="Johnson 2002">Johnson, C. Obesity, Weight Management and Self-Esteem. In: Wadden, T.A. and Stunkard, A.J Handbook of Obesity Treatment. 2002. New York, NY: Guilford Press, pp.480-493.</ref> reports that care providers who approach the issue by attempting to 'break through the patient’s denial of their weight issues, are more likely abolishing the patients trust and their motivation to return for future sessions and care. This is the most common outcome when individuals are advised to battle their obesity by losing weight, to avoid the ominous medical consequences. <br>More desirable and beneficial outcomes can be achieved through the use of motivational interviewing and discussions with patients in need of weight management compared to a confrontational approach <ref name="Miller and Rolnick 2002">Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. Book Review.</ref><ref name="Wadden and Didie 2003" />.<br> | ||

=== Teaching Tools === | |||

Tools such as the video below can be used in teaching and motivating patients on lifestyle and behaviour change. | |||

{{#ev:youtube|aUaInS6HIGo|700}} | |||

== Motivational Interviewing == | == Motivational Interviewing == | ||

Evidence has shown that patient-centred approaches to health care consultations are more effective than the traditional advice giving, especially when lifestyle and behaviour change are part of the treatment<ref name=":0">Britt E, Hudson SM, Blampied NM. Motivational interviewing in health settings: a review. Patient education and counseling. 2004 May 1;53(2):147-55.</ref>. | |||

= | In the past, healthcare practitioners encouraged patients to change their lifestyle habits through provision of direct advice about behaviour change<ref name=":1">Rollnick S, Butler CC, Kinnersley P, Gregory J, Mash B. Motivational interviewing. Bmj. 2010 Apr 27;340:c1900.</ref>. However, this has proven to be unsuccessful, as evidence show success rates of only 5-10%<ref>Rollnick S, Kinnersley P, Stott N. Methods of helping patients with behaviour change. British Medical Journal. 1993 Jul 17;307(6897):188-90.</ref> . Additionally, this can put a strain on the patient-therapist relationship with the patient perceiving this style as being lectured on their lifestyle choices<ref>Stott NC, Pill RM. ‘Advise yes, dictate no’. Patients’ views on health promotion in the consultation. Family Practice. 1990 Jun 1;7(2):125-31.</ref>. | ||

= | Patients can also feel that the therapist is not considering the personal implications the change may have on their life, as they are just placing emphasis on the future benefits and not recognising the initial struggle the patient may have to go through<ref name=":0" />. Such an encounter can risk the patient becoming resistant to change or further increasing their resistance to change<ref>Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. Guilford press; 2012 Sep 1.</ref>. This resistance to change was seen as a personality trait that could only be dealt with by direct confrontation which potentially placed a further strain on the patient-therapist relationship <ref>Miller WR. Motivational interviewing: III. On the ethics of motivational intervention. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1994 Apr;22(2):111-23.</ref>. | ||

== | Research has shown that patient-centred approaches have better outcomes in terms of patient involvement and compliance<ref name=":0" /> <ref>Ockene JK, Kristeller J, Goldberg R, Amick TL, Pekow PS, Hosmer D, Quirk M, Kalan K. Increasing the efficacy of physician-delivered smoking interventions. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1991 Jan 1;6(1):1-8.</ref>. The key feature to these approaches is that the patient actively engages in discussing a solution for their problem<ref name="Emmons & Rollnick">Emmons KM, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in health care settings: opportunities and limitations. American journal of preventive medicine. 2001 Jan 1;20(1):68-74.</ref>. | ||

== | [[Motivational Interviewing]] (MI) is based off Miller & Rollnick’s (1991)<ref>Miller, WR., Rollnick, SR. 1991. Motivational Interviewing: preparing people to change behaviour. New York: Guilford Press</ref> experience with treatment for problem drinkers and is becoming increasingly popular in healthcare settings. The model views motivation as a state of readiness to change rather than a personality trait<ref name=":2">Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler C. Motivational interviewing in health care: helping patients change behavior. Guilford Press; 2008.</ref>. As such, motivation can fluctuate over time and between situations. It can also be encouraged to go in a particular direction. By taking this view , a patient’s resistance to change is no longer seen as a trait of the person but rather something that is open to change<ref name=":1" />. Therefore, the main focus of MI is to facilitate behaviour change by helping the patient explore and resolve their ambivalence to the change<ref name=":1" />. | ||

=== | While MI is patient centred and focuses on what the patient wants, thinks and feels, it differs slightly from other patient-centred approaches as it is directive<ref name=":0" />. In using MI there is the clear goal of exploring the patient’s resistance to change in such a way that the patient is likely to change their behaviour in the desired direction<ref name=":0" />. <br>The focus of Motivational Interviewing is to: | ||

* Assist the patient in examining their expectations about the consequences of engaging in their behaviour. | |||

* Influence their perceptions of their personal control over the behaviour through use of specific techniques and skills.<ref name=":2" />. | |||

A benefit to this approach is that time can be saved by avoiding unproductive discussion by using rapid engagement to focus on the changes that make a difference<ref name=":1" />. For more on this topic see [[Motivational Interviewing]] | |||

</div> | |||

== | == Conclusion == | ||

<div> | |||

Communication is more than just what we say, it matters how we say it too. It is important that communication is good, clear and compassionate in a healthcare setting. The style in which we communicate may differ between individual patients due to learning styles, literacy levels or the level of understanding the patient has of their condition and the anxiety they may present with. | |||

<references /> | == References == | ||

<references /></div> | |||

[[Category:Osteoarthritis]] | |||

[[Category:Obesity]] | |||

[[Category:Pain]] | |||

[[Category:Primary Contact]] | |||

[[Category:Rehabilitation Foundations]] | |||

[[Category:Mental Health]] | |||

[[Category:Communication]] | |||

[[Category:Current and Emerging Roles in Physiotherapy Practice]] | |||

[[Category:Queen Margaret University Project]] | |||

Latest revision as of 11:22, 16 November 2023

Original Editor - Robyn Holton, Frank Ryan, Shawn Swartz, Elaine McDermott, Noel McLoughlin, Zeeshan Mundhas part of Queen Margaret University's Current and Emerging Roles in Physiotherapy Practice Project

Top Contributors - Elaine McDermott, Frank Ryan, Robyn Holton, Shawn Swartz, Kim Jackson, Lauren Lopez, Admin, 127.0.0.1, Zeeshan Hussain Mundh, Noel McLoughlin, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Rucha Gadgil, Aimee Tow and Jess Bell

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Effective communication techniques in a healthcare setting have been developed on the basis that physiotherapists are in a unique position as part of a multidisciplinary team in that they can have substantially more contact time with patients than other members of the team. This means the physiotherapist is more appropriately positioned to develop a deeper patient-therapist relationship and in doing so educate and empower the patient of their physical condition and management.

Communication is an important tool in a healthcare setting that when used effectively can educate, empower and de-threaten common health issues patients present within practice. However, if it is used ineffectively it can have detrimental effects creating fear, confusion and anxiety in patients as well as encouraging resistance to lifestyle changes and healthy behaviours.

Importance of Good Communication[edit | edit source]

Communication is an interactive process which involves the constructing and sharing of information, ideas and meaning through the use of a common system of symbols, signs. and behaviours[1]. It includes the sharing of information, advice, and ideas with a range of people using:

- Verbal

- Non-verbal

- Written

- E-based

These can be modified to meet the patient's preferences and needs.

Skilled and appropriate communication is the foundation of effective practice and is a key professional competence (See CSP: quality assurance standards[1] and HCPC: Standards of Proficiency[2] figure 2, above) which is highly valued by physiotherapy recipients[3]. Effective communication requires consideration of the context, the nature of the information to be communicated and engagement with technology, particularly the effective and efficient use of Information and Communication Technology.

Benefits of Good Communication[edit | edit source]

Effective communication does not only improve understanding between health professionals and patients but it can also have a positive impact on health outcomes. To understand why communication may lead to improved health outcomes researchers have identified direct and indirect pathways through which communication influences health and well being.[4].

Direct Pathways[edit | edit source]

Talk may be therapeutic, meaning, a physiotherapist who validates the patients perspective or expresses empathy may help a patient experience improved psychological well being. Leading to the patient experiencing fewer negative emotions (e.g. fear and anxiety) and more positive ones (e.g., hope, optimism and self-worth).

Non-verbal behaviours such as touch or tone of voice may directly enhance well-being by lessening anxiety or providing comfort[5][6][7]

Indirect Pathways[edit | edit source]

In most cases, communication affects health through a more indirect or mediated route through proximal outcomes of the interaction, such as;

- Satisfaction with care

- Motivation to adhere

- Trust in the clinician and system

- Self-efficacy in self care

- Clinician - patient agreement

- Shared understanding

This could affect health or that could contribute to the intermediate outcomes (e.g., adherence, self-management skills, social support that lead to better health[8].

A physiotherapists clear explanation and expression of support could lead to greater patient trust and understanding of treatment options[4]. This in turn may facilitate patient adherence to recommended therapy, which in turn improves the particular health outcome. Increased patient participation in the consultation could help the physiotherapist better understand the patient’s needs and preferences as well as discover possible misconceptions the patient may have about treatment options[4]. The physiotherapist can then have the opportunity to communicate risk information in a way that the patient understands. This could lead to mutually agreed upon, higher quality decisions that best match the patients circumstances[4]. Key factors of communication to improve health outcomes:

- Examination and Assessment - using clear concise language and allowing the patient time to talk will influence the quantity, quality and accuracy of data

- Respect Clients individuality and background - adjusting tone and level of language as well as using lay terms rather than medical terms can help improve understanding and make patients feel at ease[9][10]

- Respect a patients space - do not invade their space without first asking permission

- Be open and create a relaxed atmosphere

- Be attentive - Look at the patient when they are talking

- Environment - Provide the patient with an area that is private and away from noise and interruptions

Communicating Sensitive Issues[edit | edit source]

Primary care providers and particularly physiotherapists are often faced with sensitve issues within their daily practice. One example is dealing with obesity and encouraging patients to take a more active approach in the management of obesity[11]. However physiotherapists have encountered many challenges related to addressing obesity with patients[12]. Given that obesity is becoming an epidemic in many nations throughout the world, the need to understand how, when and with whom to have these discussions which becomes essential in order to provide effective care for obese patients. There is a growing need for the training of physiotherapists in areas such as weight loss counseling in order to reduce the barriers encountered when discussing obesity [12].

Wadden & Didie[13] reported that patients observed the terms obesity and fatness to be very undesirable descriptors used by their physicians when discussing their body weight. Other terms such as large size, heaviness and excess fat were also highlighted as undesirable. The use of these terms by physicians can be interpreted as offensive or hurtful by the patient and lead to a breakdown in communication.

The study reported that weight was the most favourably rated term to be used by physicians as it is easily understood and non judgemental. Another term which was viewed as favourably, as it was non judgemental was BMI, however it is found to be not universally known.

Johnson[14] reported that some patients preferred to be described as plus sized, large or even fat. By embracing these terms these patients are motivated to remove the negativity and stigma related to them.

Wadden and Didie[15] reported the most beneficial approach would be to ask the patient how they feel and their thoughts towards their weight. Using this approach the physiotherapist should seek the patients consent and come to an agreement to address and discuss the issue. Caution should be taken to avoid reiterating the hazards obesity has to the patients health. Wadden et al[16], reported obese patients often experience a feeling that care providers seldom understand how much they suffer with their weight issues. Utilising the conversation approach also allows the physiotherapist to show respect and empathy to the patient by focusing on the positive steps they may have taken previously to tackle the issue.

The Issue With "Calling It As It Is"[edit | edit source]

This approach fails to avoid the degrading and offensive terms, used by the public, and causes more negative effects than beneficial effects [14]. It is a challenge for obese individuals to understand the medical implication of these terms as they cannot separate them from the degrading aspects of the terms used by the public.Using a confrontational approach instead of a discussion with the patient is far more likely to negatively affect the patient’s moral, feelings and confidence. Johnson[14] reports that care providers who approach the issue by attempting to 'break through the patient’s denial of their weight issues, are more likely abolishing the patients trust and their motivation to return for future sessions and care. This is the most common outcome when individuals are advised to battle their obesity by losing weight, to avoid the ominous medical consequences.

More desirable and beneficial outcomes can be achieved through the use of motivational interviewing and discussions with patients in need of weight management compared to a confrontational approach [17][15].

Teaching Tools[edit | edit source]

Tools such as the video below can be used in teaching and motivating patients on lifestyle and behaviour change.

Motivational Interviewing[edit | edit source]

Evidence has shown that patient-centred approaches to health care consultations are more effective than the traditional advice giving, especially when lifestyle and behaviour change are part of the treatment[18].

In the past, healthcare practitioners encouraged patients to change their lifestyle habits through provision of direct advice about behaviour change[19]. However, this has proven to be unsuccessful, as evidence show success rates of only 5-10%[20] . Additionally, this can put a strain on the patient-therapist relationship with the patient perceiving this style as being lectured on their lifestyle choices[21].

Patients can also feel that the therapist is not considering the personal implications the change may have on their life, as they are just placing emphasis on the future benefits and not recognising the initial struggle the patient may have to go through[18]. Such an encounter can risk the patient becoming resistant to change or further increasing their resistance to change[22]. This resistance to change was seen as a personality trait that could only be dealt with by direct confrontation which potentially placed a further strain on the patient-therapist relationship [23].

Research has shown that patient-centred approaches have better outcomes in terms of patient involvement and compliance[18] [24]. The key feature to these approaches is that the patient actively engages in discussing a solution for their problem[25].

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is based off Miller & Rollnick’s (1991)[26] experience with treatment for problem drinkers and is becoming increasingly popular in healthcare settings. The model views motivation as a state of readiness to change rather than a personality trait[27]. As such, motivation can fluctuate over time and between situations. It can also be encouraged to go in a particular direction. By taking this view , a patient’s resistance to change is no longer seen as a trait of the person but rather something that is open to change[19]. Therefore, the main focus of MI is to facilitate behaviour change by helping the patient explore and resolve their ambivalence to the change[19].

While MI is patient centred and focuses on what the patient wants, thinks and feels, it differs slightly from other patient-centred approaches as it is directive[18]. In using MI there is the clear goal of exploring the patient’s resistance to change in such a way that the patient is likely to change their behaviour in the desired direction[18].

The focus of Motivational Interviewing is to:

- Assist the patient in examining their expectations about the consequences of engaging in their behaviour.

- Influence their perceptions of their personal control over the behaviour through use of specific techniques and skills.[27].

A benefit to this approach is that time can be saved by avoiding unproductive discussion by using rapid engagement to focus on the changes that make a difference[19]. For more on this topic see Motivational Interviewing

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Communication is more than just what we say, it matters how we say it too. It is important that communication is good, clear and compassionate in a healthcare setting. The style in which we communicate may differ between individual patients due to learning styles, literacy levels or the level of understanding the patient has of their condition and the anxiety they may present with.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Quality Assurance Standards for Physiotherapy Service Delivery. (2012). Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (CSP).

- ↑ Standards of Proficiency - Physiotherapists. (2013). Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC).

- ↑ Parry RH, Brown K. Teaching and learning communication skills in physiotherapy: What is done and how should it be done?. Physiotherapy. 2009 Dec 1;95(4):294-301.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Street Jr RL, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician–patient communication to health outcomes. Patient education and counseling. 2009 Mar 1;74(3):295-301.

- ↑ Henricson M, Ersson A, Määttä S, Segesten K, Berglund AL. The outcome of tactile touch on stress parameters in intensive care: a randomized controlled trial. Complementary therapies in clinical practice. 2008 Nov 1;14(4):244-54.

- ↑ Knowlton GE, Larkin KT. The influence of voice volume, pitch, and speech rate on progressive relaxation training: application of methods from speech pathology and audiology. Applied psychophysiology and biofeedback. 2006 Jun 1;31(2):173-85.

- ↑ Weze C, Leathard HL, Grange J, Tiplady P, Stevens G. Evaluation of healing by gentle touch in 35 clients with cancer. European journal of oncology nursing. 2004 Mar 1;8(1):40-9.

- ↑ Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1995 May 1;152(9):1423.

- ↑ Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1995 May 1;152(9):1423.

- ↑ Donovan J. Patient education and the consultation: the importance of lay beliefs. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 1991 Jun;50(Suppl 3):418.

- ↑ Stafford RS, Farhat JH, Misra B, Schoenfeld DA. National patterns of physician activities related to obesity management. Archives of Family Medicine. 2000 Jul 1;9(7):631.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Alexander SC, Østbye T, Pollak KI, Gradison M, Bastian LA, Brouwer RJ. Physicians' beliefs about discussing obesity: results from focus groups. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2007 Jul;21(6):498-500.

- ↑ Wadden TA, Didie E. What's in a name? Patients’ preferred terms for describing obesity. Obesity Research. 2003 Sep;11(9):1140-6.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Johnson, C. Obesity, Weight Management and Self-Esteem. In: Wadden, T.A. and Stunkard, A.J Handbook of Obesity Treatment. 2002. New York, NY: Guilford Press, pp.480-493.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Wadden TA, Didie E. What's in a name? Patients’ preferred terms for describing obesity. Obesity Research. 2003 Sep;11(9):1140-6.

- ↑ Wadden TA, Anderson DA, Foster GD, Bennett A, Steinberg C, Sarwer DB. Obese women's perceptions of their physicians' weight management attitudes and practices. Archives of Family Medicine. 2000 Sep 1;9(9):854.

- ↑ Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. Book Review.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Britt E, Hudson SM, Blampied NM. Motivational interviewing in health settings: a review. Patient education and counseling. 2004 May 1;53(2):147-55.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Rollnick S, Butler CC, Kinnersley P, Gregory J, Mash B. Motivational interviewing. Bmj. 2010 Apr 27;340:c1900.

- ↑ Rollnick S, Kinnersley P, Stott N. Methods of helping patients with behaviour change. British Medical Journal. 1993 Jul 17;307(6897):188-90.

- ↑ Stott NC, Pill RM. ‘Advise yes, dictate no’. Patients’ views on health promotion in the consultation. Family Practice. 1990 Jun 1;7(2):125-31.

- ↑ Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. Guilford press; 2012 Sep 1.

- ↑ Miller WR. Motivational interviewing: III. On the ethics of motivational intervention. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1994 Apr;22(2):111-23.

- ↑ Ockene JK, Kristeller J, Goldberg R, Amick TL, Pekow PS, Hosmer D, Quirk M, Kalan K. Increasing the efficacy of physician-delivered smoking interventions. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1991 Jan 1;6(1):1-8.

- ↑ Emmons KM, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in health care settings: opportunities and limitations. American journal of preventive medicine. 2001 Jan 1;20(1):68-74.

- ↑ Miller, WR., Rollnick, SR. 1991. Motivational Interviewing: preparing people to change behaviour. New York: Guilford Press

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler C. Motivational interviewing in health care: helping patients change behavior. Guilford Press; 2008.