Down Syndrome (Trisomy 21): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m (Protected "Down Syndrome (Trisomy 21)" ([Edit=⧼protect-level-ppadmin⧽] (indefinite) [Move=⧼protect-level-ppadmin⧽] (indefinite))) |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 12:07, 17 April 2023

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Down Syndrome (DS) is a chromosomal alteration[1]. Chromosomes are structures found in every cell of the body that contain genetic material and are responsible for determining anything ranging from your eye colour to your height[2]. Typically, each cell has 23 pairs of chromosomes, with half coming from each parent [2]. Down syndrome, however, occurs when chromosome 21 has a full or partial extra copy in some, or all, of that individual’s cells[1]. This triple copy is sometimes called trisomy 21[1] . The altered number of chromosomes leads to common physical features in the DS population, such as

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

DS is the most commonly occurring chromosomal variance noted worldwide, with 1 in 1000 births resulting in a child with DS[1] [3][4]. In the UK alone, there are approximately 40,000 people living with Down Syndrome, and 750 new born with DS each year [3]. Birth rates are expected to stay the same, but the total population of persons with DS is expected to rise in the coming years. This is mainly due to medical advancements which have increased life expectancy from age 9 in 1929, to 60 years of age today [5]. With this increase in the number and age of this population, there will be a larger demand on health services, such as physiotherapy, and increased challenges for families to overcome.

Additionally, persons with DS already report having problems gaining access to health care [6] with the main barrier being a lack of knowledge about available services [7]. Furthermore, parents of persons with DS also commonly express feeling stressed and uncertain about surrounding care of their child and state that they desire more help from physical activity specialists regarding both education and available interventions [8].

Signs and Symptoms[edit | edit source]

Though there are many similarities across the DS population, there is great variation in the syndrome. There are three types of DS, each with its own set of challenges and individual variation. The three types of DS are Trisomy 21 (95%), Translocation (3%-4%) and Mosaicism (1%)[9]. Whichever the type, persons with DS typically have poorer overall health at a young age and exhibit a greater loss of health, mobility, and increased secondary complications as they age when compared to their non-DS counterparts [10][11]. As a result, persons with DS and their families frequently access a range of health services, including physiotherapy.

Physical Characteristics[edit | edit source]

- Growth failure

- Flat posterior aspect of the head

- Abnormal ears

- Broad flat face

- Slanting eyes

- Epicanthic eyefold

- Short nose

- Small and arched palate

- Big wrinkled tongue

- Dental anomalies

- Short + broad hands

- Special skin ridge patterns

- Unilateral/bilateral absence of one rib

- Congenital heart disease

- Intestinal blockage

- Enlarged colon

- Umbilical hernia

- Abnormal pelvis

- Diminished muscle tone

- Big toes widely spread

Medical conditions[edit | edit source]

Although DS itself is not a medical condition but is simply a common variation in the human form, there are many medical conditions that people with DS frequently experience. These include:

- Learning difficulties

- Poor cardiac health

- Thyroid dysfunction

- Diabetes

- Obesity

- Digestive problems

- Low bone density

- Hearing and Vision loss

- Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease

- Depression

- Leukaemia

Developmental Milestones in Children with Down Syndrome[edit | edit source]

From the time a child is born, they grow and learn at their own pace. However, some skills are expected to be mastered by a specific age. These are called developmental milestones. Milestones can be physical achievements, language-related, or social accomplishments [12].

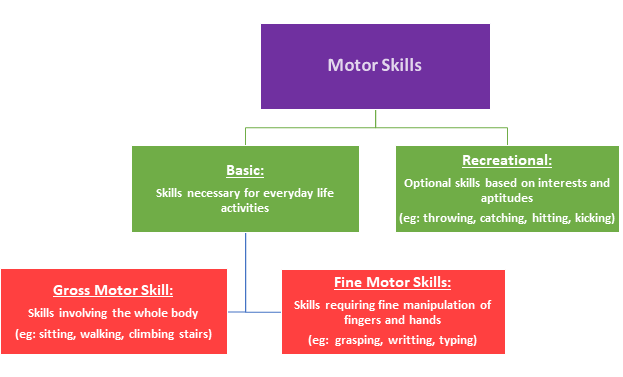

The ability to move is essential to human life and development. All children begin developing a wide range of movement skills, or motor skills, starting at birth. These motor skills are wide-ranging and often broken down into the sub-sections below:

Persons with DS will generally achieve all the same basic motor skills necessary for everyday living and personal independence, however, it may be at a later age and with less refinement compared to those without DS [13]. Some adjusted milestones for DS are available below:

While these milestones are generally agreed upon, studies targeting developmental milestones tend to only examine a small number of people. This makes the information less representative of the entire DS population. Researchers also commonly compare people with DS to their non-DS counterparts of the same age. This is an invalid comparison, and it would be more correct to compare children with DS to non-DS individuals of the same mental age. Despite these limitations, the above-listed milestones are widely used and considered accurate [15].

Balance and Down Syndrome[edit | edit source]

It is common for children with DS to be delayed in reaching common milestones such as sitting independently, standing and walking. One of the contributing factors to the delay of these specific milestones is poor balance. It is well known that persons with DS are often considered floppy, clumsy, uncoordinated and have awkward movement patterns due to balance issues. These balance challenges often follow the child into the teen years and sometimes into adulthood [16]. While impaired balance is difficult on its own, it may also impact the development of other motor abilities and cognitive development. Being able to maintain balance allows for exploration, social interaction and overall freedom [17].

Understanding the underlying factors contributing to poor balance can ensure help to plan individual interventions and strategies to enhance their quality of life. Some of the route causes of balance difficulties are:

- Ligament Laxity: This results inelastic/loose joints and a large range of movement, which can lead to instability and poor control.

- Low Muscle Tone: are characterised by the ‘floppy’ appearance of limbs, with little activity in the muscles at rest, impacting stationary balance. This can improve over time but can influence balance greatly in the early years.

- Slow Reaction Times/Speed of Movement: This means that even if the person feels unsteady, it will take a longer time to react to this feeling, and once it is understood, the corrective movement will also be delayed.

- Differences in Brain Size: Persons with DS typically have smaller cerebellums, which is a part of the brain that contributes to the control of balance. The small size impacts its function, limiting balance reflexes, and causing blurry vision when completing tasks at high speed. Other parts of the brain are also smaller, creating issues with voluntary activities, walking technique and coordination.

- Poor Postural Control: Typically the posture of a person with DS is slouched - hunched over, with a rounded neck. This prevents the head and body from sitting over the pelvis. Posture is impacted by inaccurate messages being sent to the brain from the body’s sensory system. This leaves people with DS less capable of adapting or making anticipatory adjustments to changing environments [17][18][19].

Strength and Down Syndrome[edit | edit source]

Another contributing factor to delayed milestones and common challenge with DS is decreased strength.

During childhood, children with DS do not experience the same amount of muscle growth or strength increase as their peers without DS [20]. This is in part due to the decreased amount of physical activity experienced by people with DS but is also caused by unknown genetic reasons that research is still investigating. Regardless of the reason, persons with DS consistently fall behind in strength categories when compared to their peers without DS, individuals with DS typically exhibiting 40-50% less strength [21].

Decreased strength can have a large impact on the lives of persons with DS. Not only can it lead to complication of activities of daily living, making walking up the stairs, getting out of a seat and other seemingly simple tasks, major obstacles, but it can also lead to other problems. Some of these are listed below:

- Increased wear and tear on joints

- Contributes to reduced balance due to weakness of the stability muscles

- Higher risk of falls

- Elevated level of fatigue

- Delayed developmental milestones

- Increased risk of osteoporosis [22]

Reduced Levels of Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

The research on physical activity levels in people with Down syndrome is conflicting. However, most research does find people with Down syndrome live highly sedentary lives in which they do not achieve the recommended guidelines for physical activity levels [23][24]. The daily recommended levels of physical activity for children is at least 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous-intensity activity, and for adults the recommended levels is at least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity each week, including at least two strength session in the week [25][26]. Although people with Down syndrome may have decreased capacity for exercise compared to their peers without DS, the guidelines clearly state that children with DS should still meet the recommended guidelines or do as much physical activity as they can manage [27].

Furthermore, as people with DS age, their physical activity levels fall even further behind their peers without DS [23][28][29]. This trend demonstrates that reduced activity levels are a lifelong issue for children with DS that must be addressed.

Barriers to Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

Most individuals with Down’s Syndrome have to overcome social and environmental barriers to access physical activity. People with DS face many obstacles with the main barriers being lack of money, transportation, access to programs and support from family and carers. It is a common thought that people with DS are too fragile to participate in exercise. [30].

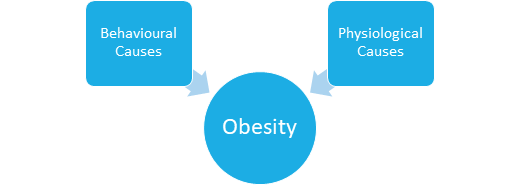

Poor strength and balance are limitations to both cardiovascular and resistance exercise, however, this needs to be addressed as many individuals with DS are now being classed as obese. Individuals with Down syndrome have been found to have substantially higher rates of obesity compared to the general population [31]. Often occurring early on in childhood, obesity was found to remain stable from childhood into adulthood, with slight increases after puberty [32]. Obesity is now recognized as a major health risk for people with Down syndrome [33].

The causes of obesity in the Down syndrome population can be divided into physiological causes and behavioural causes. Physiological causes may include conditions such as hypothyroidism, decreased metabolic rate, increased leptin levels (a hormone which helps regulate hunger), short stature and low levels of lean body mass [34]. Behavioural tendencies such as negative thinking and inattention behaviour may become barriers that prevent vital dietary and lifestyle changes to occur [34].

Physical inactivity also increases the chance for the development of other health problems such as diabetes, increased blood pressure, dyslipidaemia, early markers of cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal disorders, breathing difficulties with worsening of sleep apnea and psychological effects including reduced quality of life [25][34].

Aerobic fitness in both youth and adults with Down syndrome is reduced compared to their peers without DS [35][36]. Studies find that adolescents and young adults with DS have comparable aerobic fitness to non-DS older adults (60years +) with heart disease [36]. They also have lessened aerobic abilities, reduced muscular strength and reduced bone mineral density levels by 26% compared to their peers without DS [37].

Benefits of Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

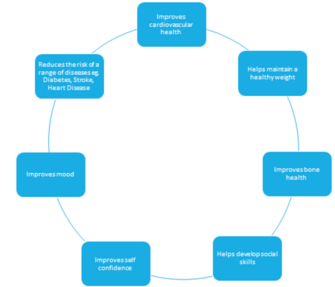

Overall, strong evidence suggests that regular physical activity can lead to numerous health benefits. Participating in physical activity has a positive impact on people’s health. Benefits include improved cardiovascular, metabolic, musculoskeletal and psychosocial health profiles in people with and without DS [38].

The fact that many children with DS reach Developmental Milestones later than their peers may be a contributing factor to lower levels of physical activity during infancy.[39] Onset of independent walking in children with Down syndrome occurs roughly 1 year later in comparison to children with typical development [40]. Earlier walking onset has been observed in infants with Down syndrome who performed greater amounts of high-intensity activity at 1 year of age [41]. Changes to physical activity levels in infants with Down syndrome has been suggested to encourage motor development, validating the importance of early physiotherapy intervention [39].

Some health benefits of increased physical activity levels in persons with DS are:

- Decreased body fat percentage

- Decreased body weight

- Improved cardiovascular fitness

- Improved muscle strength

- Decreased depression

- Reduced risk of osteoporosis[42][43][44][45]

In addition to the health benefits listed above, physical activity is important for people with DS because it:

- Promotes the development of physical and social skills.

- Establishes a regular routine around being physically active, leading to better habits in the future.

- Increases life satisfaction.

- Prevents secondary conditions associated with DS including diabetes, osteoporosis and dementia [46].

From the evidence, it is clear that physical activity is integral to a person with Down syndrome’s health, fitness and wellbeing [27].

Sensation[edit | edit source]

In addition to the other challenges facing people with DS, they can also experience sensory issues [47]. Being unable to process sensory information from the environment, sensory integration, can be both frustrating and challenging, often leading to inappropriate behaviour as a response [48]. As humans, we use sensory information to gain experience, learn and interact with the world. When sensory feedback is limited, it can impact progress in other areas such as motor development [47]. Sensory difficulties can impact a child’s behaviour and the way they interact with people and objects around them [48].

Mental Health and Emotional Wellbeing[edit | edit source]

It is not uncommon for individuals with Down syndrome to experience challenges with emotional behaviours and mental health. Children with Down syndrome may have difficulties with communication skills, problem-solving abilities, inattentiveness and hyperactive behaviours. Adolescents may be susceptible to social withdrawal, reduced coping skills, depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive behaviours and sleep difficulties. Adults with DS may have similar experiences as adolescents, with further complications of dementia and alzheimer's later in life [50].

Physiotherapy Management and the Role of the Multidisciplinary Team[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy and the multidisciplinary team plays a major role in supporting individuals with DS by adopting an holistic approach to their diverse needs[51]. Not everyone with DS will require physiotherapy intervention but at some point may need advice from occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, psychologists and other healthcare professionals.

Physiotherapists provide tailored interventions to improve physical abilities, strength, and balance, while occupational therapists focus on enhancing daily living skills, fine motor control, and sensory processing. Speech and language therapists help individuals with DS develop effective communication skills and address feeding and swallowing challenges. Psychologists support emotional and cognitive well-being, helping individuals and their families cope with challenges and develop strategies for long-term success.

Although there is no standard treatment plan, effective physiotherapy management of Down syndrome typically involves a combination of sensory integration therapy, neurodevelopment treatment, perceptual-motor therapy and traditional strength and conditioning programs [52]. Physiotherapists are commonly consulted to educate individuals and their families as well as provide input on health promotion and long-term condition management [53]. Due to the variation in all people and across Down syndrome cases, no one physiotherapy intervention can be prescribed. Interventions are based on the individual’s physical and intellectual needs, as well as his or her personal strengths and limitations [54]. Some of the common issues that physiotherapists will address are:

- Delayed developmental milestones

- Balance issues

- Decreased strength

- Reduced levels of physical activity

- Issues with sensation

- Reduced mental health and emotional well-being

- High chance of Alzheimer’s disease

Choosing the right intervention based on the problems experienced and the individual child is essential to improve the outcome of treatment. Below are some examples of effective interventions for children with Down syndrome.

- Tummy time

- Neurodevelopmental Treatment (NDT)

- Sensory Integration Therapy (SIT)

- Perceptual-Motor Therapy (PMT)

- Two-Wheeled Bicycle Training

- Therapeutic Horseback Riding (Hippotherapy)

- Treadmill Training

- Balance Training

- Strength Training

- Physical Activity

As many treatments often require on-going maintenance, the team should encourage family members to support and implement home treatment plans in an attempt to encourage self-management [55]. By fostering strong communication among the team members and families, the multidisciplinary rehabilitation team can make a lasting impact on the lives of individuals with Down syndrome, helping them achieve their full potential and lead more independent lives.

Resources[edit | edit source]

The following video “Ted Talk” presented by Karen Gaffney, a person with Down Syndrome, explores numerous contemporary thoughts surrounding DS and challenges society's preconceptions of people with DS.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 National Down Syndrome Society. What is down syndrome. London: NDSS. https://www.ndss.org/about-down-syndrome/down-syndrome/ (accessed 09 March 2022).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 National Human Genome Research Institute. Chromosome. Available from https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Chromosome (accessed 9 March 2022).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Learning Disability Today. Spotlight on: Down Syndrome. Available from https://www.learningdisabilitytoday.co.uk/spotlight-on-downs-syndrome (accessed 09 March 2022).

- ↑ Windsperger K, Hoehl S. Development of Down Syndrome Research Over the Last Decades–What Healthcare and Education Professionals Need to Know. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021 Dec 14;12:749046.

- ↑ Zhu J, Hasle H, Correa A, Schendel D, Friedmant J, Olsen J, Ramussen S. Survival among people with down syndrome. Genetics in Medicine 2013;15:64-69. https://www.nature.com/articles/gim201293 (accessed 12 March 2018).

- ↑ Allerton L, Emerson E. British adults with chronic health conditions or impairments face significant barriers to accessing health services. Public Health 2012;126:920-927. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22959282 (accessed 13 March 2018).

- ↑ National Health Service. Promoting access to healthcare for people with a learning disability. www.jpaget.nhs.uk/media/186386/promoting_access_to_healtcare_for_people_with_learning_disabilities_a_guide_for_frontline_staff.pdf (accessed 14 March 2018).

- ↑ Menear, K. Parents perceptions of health and physical activity needs of children with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome Research 2007;12:60-68. https://library.down-syndrome.org/en-gb/research-practice/12/1/parents-perceptions-health-physical-activity-needs-down-syndrome/ (accessed 12 April 2018).

- ↑ Pueschel SM, editor. A parent's guide to Down syndrome: Toward a brighter future. Brookes Pub; 2001.

- ↑ British Institute of Learning Disabilities. Supporting older people with learning disabilities. https://www.ndti.org.uk/uploads/files/9354_Supporting_Older_People_ST3.pdf (accessed 18 March 2018).

- ↑ Cruzado D, Vargas, A. Improving adherence physical activity with a smartphone application based on adults with intellectual disabilities. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1173. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1173 (accessed 11 March 2018).

- ↑ Sacks B, Buckley S. What do we know about the movement abilities of children with down syndrome. Down Syndrome News and Updates 2003;2:131-141. https://library.down-syndrome.org/en-gb/news-update/02/4/movement-abilities-down-syndrome/ (accessed18 March 2018).

- ↑ Kim H, Kim S, Kim J, Jeon H, Jung D. Motor and cognitive developmental profiles in children with down syndrome. Annals of Rehabilitation Medicine 2017;41:97-103. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5344833/ (accessed 21 March 2018).

- ↑ National Down Syndrome Society. Down Syndrome Developmental Milestones. 2009. [Picture]. https://www.ndss.org/resources/early-intervention/ (accessed 12 March 2018).

- ↑ Frank K, Esbensen A. Fine motor and selfcare milestones for individuals with down syndrome using a retrospective chart review. Journal of Theoretical Social Psychology. 2015;89:719-729. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jir.12176 (accessed 20 March 2018).

- ↑ Georgescu M, Cernea M, Balan V. Postural control in down syndrome subjects. The European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences. www.futureacademy.org.uk/files/images/upload/ICPESK%202015%2035_333.pdf (accessed 17 March 2018).

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Malak R, Kostiukow A, Wasielewska A, Mojs E, Samborski W. Delays in motor development in children with down syndrome. Medical Science Monitor 2015;21:1904-1910. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4500597/ (accessed18 March 2018).

- ↑ Costa A. An assessment of optokinetic nystagmus in persons with down syndrome. Experimental Brain Research 2011;8:110-121. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/08/110824142850.htm (accessed17 March 2018).

- ↑ Saied B, Hassan D, Reza B. Postural stability in children with down syndrome. Medicina Sportiva 2014;1:2299-2304. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1510494760/fulltextPDF/6606B032D8C04A9EPQ/1?accountid=12269 (accessed19 March 2018).

- ↑ Cowley P, Ploutz-Snyder L, Baynard T, Heffernan K, Jae S, Hsu S. Physical fitness predicts functional tasks in individuals with Down syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exercise 2010;42:388-393.

- ↑ Mercer V, Stemmons V, Cynthia L. Hip abductor and knee extensor muscle strength of children with and without Down’s syndrome. Phys Ther 2001;1318-26.

- ↑ Merrick J, Ezra E, Josef B, Endel D, Steinberg D, Wientroub S. Musculoskeletal problems in Down syndrome. Israeli J Pediatr Orthop 2000;9:185-192.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Esposito PE, MacDonald M, Hornyak JE, Ulrich DA. Physical activity patterns of youth with Down syndrome. Intellectual and developmental disabilities 2012 Apr;50(2):109-19.

- ↑ Phillips AC, Holland AJ. Assessment of objectively measured physical activity levels in individuals with intellectual disabilities with and without Down's syndrome. PLoS One 2011 Dec 21;6(12):e28618.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 WHO | Physical Activity and Adults [Internet]. Who.int. 2011 [cited 9 April 2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_adults/en/

- ↑ WHO | Physical activity and young people [Internet]. Who.int. 2011 [cited 9 April 2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_young_people/en/

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Shields N, Blee F. Physical activity for children with Down syndrome. 2012.

- ↑ Shields N, Dodd KJ, Abblitt C. Do children with Down syndrome perform sufficient physical activity to maintain good health? A pilot study. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly. 2009 Oct;26(4):307-20.

- ↑ Buckley S. Increasing opportunities for physical activity. Down Syndrome Research and Practice 2007;12:18-19.

- ↑ Barr M, Shields N. Identifying the barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity for children with Down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2011 Nov 1;55(11):1020-33.

- ↑ Rimmer JH, Yamaki K, Davis BM, Wang E, Vogel LC. Peer reviewed: Obesity and overweight prevalence among adolescents with disabilities. Preventing chronic disease. 2011 Mar;8(2).

- ↑ Basil JS, Santoro SL, Martin LJ, Healy KW, Chini BA, Saal HM. Retrospective study of obesity in children with Down syndrome. The Journal of pediatrics. 2016 Jun 1;173:143-8.

- ↑ Bull MJ. Health supervision for children with Down syndrome. 2011.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Artioli T. Understanding Obesity in Down’s Syndrome Children. Journal of Obesity and Metabolism. 2017 1: 101.

- ↑ Mendonca GV, Pereira FD, Fernhall BO. Reduced exercise capacity in persons with Down syndrome: cause, effect, and management. Therapeutics and clinical risk management. 2010;6:601.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Baynard T, Pitetti KH, Guerra M, Unnithan VB, Fernhall B. Age-related changes in aerobic capacity in individuals with mental retardation: a 20-yr review. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2008 Nov;40(11):1984-9.

- ↑ Angelopoulou N, Matziari C, Tsimaras A, Sakadamis V, Mandroukas K. Bone mineral density nd muscle strength in young men with mental retardation. Calcified Tissue International 2000;66:176-180.

- ↑ Rowland T. Physical activity, fitness, and children. Physical activity and health. 2007:259-70.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Pitetti H, Baynard T, Agiovlasitis S. Children and adolescents with Down syndrome, physical fitness and physical activity. Journal of Sport and health Science 2013;2:47-57.

- ↑ Ulrich BD, Ulrich DA. Spontaneous leg movements of infants with Down syndrome and nondisabled infants. Child development. 1995 Dec 1;66(6):1844-55.

- ↑ Lloyd M, Burghardt A, Ulrich DA, Angulo-Barroso R. Physical activity and walking onset in infants with Down syndrome. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly. 2010 Jan;27(1):1-6.

- ↑ Ulrich DA, Burghardt AR, Lloyd M, Tiernan C, Hornyak JE. Physical activity benefits of learning to ride a two-wheel bicycle for children with Down syndrome: a randomized trial. Physical therapy. 2011 Oct 1;91(10):1463-77.

- ↑ Rimmer JH, Heller T, Wang E, Valerio I. Improvements in physical fitness in adults with Down syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2004 Mar;109(2):165-74.

- ↑ Seron BB, Modesto EL, Stanganelli LC, Carvalho EM, Greguol M. Effects of aerobic and resistance training on the cardiorespiratory fitness of young people with Down Syndrome. Revista Brasileira de Cineantropometria & Desempenho Humano. 2017 Aug;19(4):385-94.

- ↑ Heller T, Hsieh K, Rimmer JH. Attitudinal and psychosocial outcomes of a fitness and health education program on adults with Down syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2004 Mar;109(2):175-85.

- ↑ Shields N. Getting Active: What Does it Mean for Children With Down Syndrome?. 2016.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 BruniI M.. Fine motor skills for children with Down syndrome. 2nd ed. Bethesda: Woodbine House Inc., 2006.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Lashno M. Sensory integration: observations of children with Down syndrome and Autistic spectrum disorders. Disability Solutions 1999;3:31-35.

- ↑ Scott R. Do you know me. 2015. [Picture]. https://psychprofessionals.com.au/sensory-processing-problem/ (accessed 12 April 2018).

- ↑ Van Germeren-Oosterom H, Fekkes M, Buitendijk S, Mohangoo A, Bruil J, Van Wouwe J. Development, problem behaviour, and quality of life in a population based sample of eight-year-old children with Down syndrome. Plos One 2011;6:7.

- ↑ CSP. What is physiotherapy. 2018. www.csp.org.uk/your-health/what-physiotherapy (accessed 14 April 2018).

- ↑ Down Syndrome Association. For Families and Carers. https://www.downs-syndrome.org.uk/for-families-and-carers/ (accessed 6 April 2018).

- ↑ CSP. Learning disabilities physiotherapy. Associated of Chartered Physiotherapists for People with Learning Disabilities. www.acppld.csp.org.uk/learning-disabilities-physiotherapy (accessed13 March 2018).

- ↑ National Human Genome Research Institute. Learning about Down syndrome. https://www.genome.gov/19517824/learning-about-down-syndrome/ (accessed 16 March 2018).

- ↑ Middleton J, Kitchen S. Factors affecting the involvement of day centre staff in the delivery of physiotherapy to adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 2008:21:227-235. www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2007.00396.x/epdf (accessed 11 March 2018).

![[14]](/images/a/af/Milestones_DS.jpg)

![[49]](/images/c/c6/Elizabeth_Stick_Men.jpg)