Discharge management of the amputee

Original Editor - Barbara RAU

Top Contributors - Sheik Abdul Khadir, Admin, Kim Jackson, 127.0.0.1, Tony Lowe, Tarina van der Stockt, Simisola Ajeyalemi and Karen Wilson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Successful rehabilitation post-amputationrelies on the patient’s achievement of goals that were pre-determined by a multidisciplinary team (Multidisciplinary_management_of_the_amputee) and assessed through specific outcome measures (Outcome_measures_for_amputees). Successful rehabilitation is therefore intrinsicallylinked to effective discharge,which allows a patient to function optimally in his/her environment withthe necessary tools for proper management and self-care at home, inherent to the quality of life and empowerment of the patient. Because one can expect prosthetic usage to be altered or health status to change over time, timely re-evaluation of aforementioned outcome measures should be performed.[1] However, there is currently no clear evidence in the literature supporting the optimal process for patients’ discharge following an amputation, or suggesting determinants for the management of patients post-discharge to maintain their independence through regular follow-up.

Discharge Determinants: WHO ICF Model[edit | edit source]

The patients’ expected level of functional independence will not only be influenced by their physical and psychological presentation, but by their social environment as well.[2]

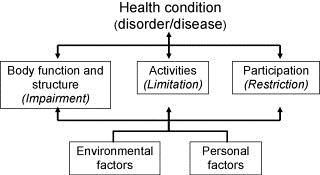

In fact, the WHO developed an international standard used to describe and measure health and function: the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, commonly known as the ICF (International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)). Instead of focusing on a patient’s diagnosis or disability, the ICF encourages health care professionals to adopt a holistic approach through a biopsychosocial model that considers all aspects present in someone’s life (health condition, environmental and personal factors) as interacting bodies that are determinant to the three level of functioning (body structure and functions, activity, and participation).

In accordance with the ICF model, Rommers et al. (1997) describe how “parameters such as physical condition, social factors, age and co-morbidity are influencing factors in determining the discharge destination” [3]. It is indeed by considering the patients’ activity and participation that the health care team can effectively direct patients towards the gradual resumption of roles within a community, whether it is practicing a sport or returning to work (International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)).

Prior to discharge, occupational and physical therapists also need to conduct a detailed interview with the patients pertaining to environmental factors. For instance, positively reinforcing the importance of the patients’ social network reintegration is paramount to their recovery and should not be over looked by the rehabilitation team [4] Together with the patient and his family, the rehabilitation team also determines the need for modifications around their home, alterations ofactivities of daily living, or relocation to a residence that provides assistance. Indeed, functional outcomes in amputees has been shown to be improved by modification of their physical environment [5].

Personal factors such as coping mechanisms in the face of bereavement or overall behavioral patternsequally need to be taken into consideration to ensure the well-being of patients during and following the maintenance phase once they are at home.

An Amputation Core Set following the ICF model

The use of the ICF in clinical practice and research is facilitated by Core Sets that serve as short lists of ICF categories, focusing on specific aspects of function typically associated with a particular disability [6] They can help guide the rehabilitation management process as described by the Swiss Paraplegic Centre (SPC), Nottwil, Switzerland (Www.icf-casestudies.org), or serve for the documentation of functioning and health in clinical studies. They are agreed upon according to specific conditions or for different health care contexts. Kohler et al integrated four preparatory studies towards the conception of a Core Set for persons following amputation. As he states in his paper, the “classification, measurement and comparison of the consequences of amputations has been impeded by the limited availability of internationally, multi-culturally, standardized instruments in the amputee setting.” [7] Once it is finalized, the Core Set for amputation will provide health care professional with a standard path to assess patients for expected outcomes, and ultimately a more specific description of the individual who underwent an amputation that will not only take into account medical conditions, but activities and participation, along with environmental and personal factors.

Return to Work[edit | edit source]

A review of the literature by Burger and Marincek [8] highlighted a recurring rate of 66% for return to work, with between 22 to 67% of subjects who maintained the same occupation and the remainder who had to change occupation. From the different studies, return to work depended on general factors such as age, educational levels, or gender (Millstein et al [9] showed that female subjects had an unemployment rate as high as 2.5 times higher than male subjects); factors related to disabilities linked to the amputation such as the amputation level, comorbidities, persistent stump issues, comfort of the prosthesis, walking distance or other restrictions in mobility; as well as factors related to the work per se such as salary, job involvement, or the support network provided by the employer or the family. The conclusion was that subjects encountered difficulties after amputation to resume their vocational activities, where many have to change their schedules to part-time work or to change their work altogether.

As return to work is one of the main goals and a measure of rehabilitation (9, 10),team members should implementeffective vocational rehabilitation and counseling for patients to guide them through the hardships of social reinsertion. A joint work and cooperation between the rehabilitation health care professionals, the company doctors, and the employers is therefore necessary towards optimal guidance of individuals [8].

The team will assist patients with vocational rehabilitation through assessment (interests, readiness for work, skills, local job opportunities), counseling and guidance, as well as planning of further treatments to increase the patient’s work potential. This process may require further education, training, or job modification.Support and job placement services also exist and can be suggested to further assist patients (assistance covering transportation or independent living costs, community services, etc).

The Amputee Clinic at the Ontario Workers’ Compensation Board in Canada is an example of centers that serve workers who have sustained an amputation as a result of a work related accident. It aims at assisting them with medical, prosthetic, psychosocial, and vocational services [9].

Self-care and Management / Patient education[edit | edit source]

Throughout the rehabilitative process, health care professionals help patients acquire the skills and tools needed to adapt to their life after amputation, through therapeutic education [10]. Pantera et al. (2014) reviewed the literature and analyzed experts opinion when looking at therapeutic education for persons after an amputation. Themes include stump pain management, phantom limb pain management, musculoskeletal pain and disorders, stump and prosthetic hygiene, falls prevention, fitting of the prosthesis, bereavement of the lost limb and managing depression, information and education on the various types of prosthetics and their use, changes in social life, perception of amputation in society, but also daily needs such as transportation, couple relationships, or sports and activities [10].

Some themes that will be covered in this article pertain to physical activity and diet, stump and prosthetic hygiene, when to contact the medical team, as well as effective follow up of patients.

Lifestyle and Habits[edit | edit source]

Amputation is a major cause of permanent disability, and it may alter the free time activities of an individual because of anxiety, depression, and isolation. Evidence is showing that physical activity can indeed prevent and treat diseases and has many added benefits for persons who face physical or psychological challenges, as advocated by the World Health Organization. [4]

The physiotherapist should providean exercise plan with clear mentions of activity restrictions if any, and ways to prevent complications such as contractures or decreased blood flow to the stump. The patient can resume his/her activities of daily living as indicated by the health care professionals, and should be encouraged to do as much as possible. This will empower the individual and improve the trust in his/her capabilities with the new prosthesis.

Healthy habits can be advocated for at that time. Dietary recommendations are all the more crucial when planning for the discharge of diabetic patients. Health care professionals need to sensitize them as to closely control their blood sugar levels, prevent sores and infections through careful skin examination and adequate shoe wear.

Stump and Prosthetic Hygiene[edit | edit source]

It is important that patients take good care of their stump and prosthesis, to avoid complications such as infection at the wound site, bed sores, pain due to improper alignment, or muscle contractures. It is important to:

- Depending on the healing stage of the wound and the doctor’s indications, keep the wound clean and dry OR wash the stump daily once the dressings have been removed, and dry it well

- Clean the area around the wound gently with mild soap and water

- Inspect the stump daily, looking for any red areas or dirt

- Wrap the stump every 2 to 4 hours with the elastic bandage, as shown by the health care team

- Wear shoes that are similar to the ones they usually wear to avoid changes in body alignment and consequent changes in pressure points in the prosthesis

- Examining the prosthesis regularly for loose parts of damaged areas

- Wear clean dry socks with the prosthesis

- Clean the prosthesis’ socket with soap and water

- Maintain a stable body weight for optimal fitting of the prosthesis

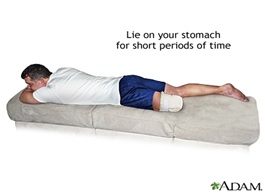

- For below the knee amputations, lie on the stomach 3-4 times a day for 20 minutes to stretch the hip muscles.

When to contact the medical team[edit | edit source]

Following discharge, patients should be confident as to when it is a good idea to contact the medical team or doctor. Some points are:

- A stump that looks more red

- The skin around the stump feels warmer

- There is swelling, bulging, or bleeding around the wound

- A foul smell is coming from the wound

- Other signs and symptoms of infection such as fever or chills

- Pain that is not well controlled with the prescribed medication

- Side effects from the medication such as dizziness, nausea, hallucinations

- If the patient has any additional question concerning the amputation or stump care

Psychological Support[edit | edit source]

BACPAR Recommendations

[edit | edit source]

References

[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Broomhead P, Clark K, Dawes D, Hale C, Lambert A, Quinlivan D, Randell T, Shepherd R, Withpetersen J. (2012) Evidence Based Clinical Guidelines for the Managements of Adults with Lower Limb Prostheses, 2nd Edition. Chartered Society of Physiotherapy: London.

- ↑ Hanley, M. A., Jensen, M. P., Ehde, D. M., Hoffman, A. J., Patterson, D. R., & Robinson, L. R. (2004). Psychosocial predictors of long-term adjustment to lower-limb amputation and phantom limb pain. Disability&Rehabilitation, 26(14-15), 882-893.

- ↑ Rommers, G. M., Vos, L. D. W., Groothoff, J. W., Schuiling, C. H., &Eisma, W. H. (1997). Epidemiology of lower limb amputees in the north of The Netherlands: aetiology, discharge destination and prosthetic use. Prosthetics and orthotics international, 21(2), 92-99.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Deans, S. A., McFadyen, A. K., & Rowe, P. J. (2008). Physical activity and quality of life: A study of a lower-limb amputee population. Prosthetics and orthotics international, 32(2), 186-200.

- ↑ Collin, C., Wade, D. T., & Cochrane, G. M. (1992). Functional outcome of lower limb amputees with peripheral vascular disease. Clinical rehabilitation, 6(1), 13-21.

- ↑ Geertzen, J. H., Rommers, G. M., & Dekker, R. (2011). An ICF-based education programme in amputation rehabilitation for medical residents in the Netherlands. Prosthetics and Orthotics international, 35(3), 318-322.

- ↑ Kohler, F. et al. (2009). Developing Core Sets for persons following amputation based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health as a way to specify functioning. Prosthetics and Orthotics International, 33(2):117-129.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Burger, H., &Marincek, C. (2007). Return to work after lower limb amputation. Disability & Rehabilitation, 29(17), 1323-1329.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Millstein, S., Bain, D., & Hunter, G. A. (1985). A review of employment patterns of industrial amputees-factors influencing rehabilitation. Prosthetics and orthotics international, 9(2), 69-78.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Pantera, E., Pourtier-Piotte, C., Bensoussan, L., &Coudeyre, E. (2014). Patient education after amputation: Systematic review and experts’ opinions. Annals of physical and rehabilitation medicine, 57(3), 143-158.