Developmental Disabilities in Early and Middle Childhood

Top Contributors - Jess Bell, Kim Jackson, Wanda van Niekerk, Naomi O'Reilly, Tarina van der Stockt, Rucha Gadgil and Cindy John-Chu

Introduction[edit | edit source]

"Developmental disabilities are a diverse group of severe chronic conditions that are due to mental and/or physical impairments. People with developmental disabilities have problems with major life activities such as language, mobility, learning, self-help, and independent living."[1]

Developmental disabilities (DDs) includes conditions such as:[2]

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Autism

- Intellectual disability

- Learning difficulties (including ADHD, developmental coordination disorder (DCD) / dyspraxia, auditory processing disorder)

- Blindness

- Cerebral palsy

- Moderate to profound hearing loss

- Seizures

- Stuttering / stammering

- Other developmental delay

The prevalence of DDs is increasing. From 1997 to 2008 autism prevalence increased by 289.5 percent and ADHD increased by 33 percent.[3] The 2009-2017 National Health Interview Survey showed a 9.5 percent increase in the prevalence of DDs in children aged 3 to 17 years.[4]

Movement Difficulties[edit | edit source]

Hypermobility[edit | edit source]

Muscle Tone[edit | edit source]

Muscle tone is defined as: “the tension in the relaxed muscle” - GANGULY i.e.

the amount of tension or resistance to stretch in a muscle. WEB

Hypotonia[edit | edit source]

Hypotonia is defined as: “poor muscle tone resulting in floppiness. It is abnormally decreased resistance encountered with passive movement of the joint.” MADHOK

There are different causes of hypotonia: WEB

- Lower motor neuron disease (neurological, metabolic and genetic causes)

- Infections (meningitis, polio)

- Genetic (Down’s syndrome, Prader-Willi, Tay-Sachs, spinal muscular atrophy, Charcot-Marie-Tooth syndrome, Marfan syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome)

- Metabolic (rickets)

- Congenital hypothyroidism

- Genetic acquired (muscular dystrophy)

- Benign congenital hypotonia (BCH)

- NB: BCH is a symptom, rather than a diagnosis. Diagnosis is made in the absence of other diagnoses (such as joint hypermobility, aspergers, autism, DCD).

- Low connective tissue tone - this is considered better terminology to describe hypermobility or increased laxity in connective tissue

- Joint hypermobility

- This term is used when only the connective tissue in the joints is affected

- Benign Joint Hypermobility Syndrome (BJHS)

Benign Joint Hypermobility Syndrome[edit | edit source]

BJHS is a hereditary condition[5] that causes musculoskeletal symptoms in hypermobile patients, without other rheumatological features being present. It appears to be caused by an abnormality in collagen or the ratio of collagen subtypes.[6]

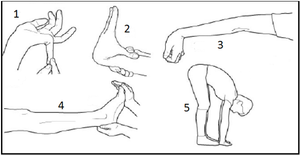

Diagnosis is made based on a medical examination and use of the Beighton score (see Figure 1)

Children with BJHS are susceptible to joint injury or dislocation, reduced stability, and a decreased ability to build muscle strength. They may tire easily, complain of pain or digestive issues, but symptoms are variable. They tend to be exacerbated during growth spurts, adolescence and hormone changes.[2]

The Good News[edit | edit source]

- Strengthening is beneficial[7]

- Swimming, pilates, climbing, horse riding can help (i.e. non-impact activities):[2]

- If children engage in high impact sports, they may require rest days (particularly if they are complaining of night pain after activity)

- Specific movement programmes such as Physifun are beneficial[2]

NB: If BJHS children participate in ballet, gym or dancing, it is important that they avoid “locking out” their joints. Instead, teach them to have “soft knees”. Also watch for lordotic postures and tight hamstrings.[2]

Social, Behaviour and Movement Difficulties[edit | edit source]

Social Communication Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder[edit | edit source]

Social (pragmatic) communication disorder (SCD) is a relatively new diagnosis, described in the DSM-5. It is characterised by problems with verbal and nonverbal social communication,[8] but individuals with this condition do not display any restricted and repetitive interests / behaviours.[9] People with SCD may, for example, have difficulty taking turns to speak, adapting their voice, making small talk, and making eye contact.[2]

Autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects how individuals communicate and interact with others. Conditions that were previously seen as separate disorders (i.e. autism, Asperger’s) are now included under the umbrella term ASD.[10]

There is a very broad spectrum of affect in ASD – from mild to very severe.[2] Individuals with ASD also display restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests or activities.[11]

Other signs of ASD are:[2]

- One-sided conversations

- Robotic monotone speech

- Awkward movements and / or mannerisms

While motor impairment is not currently part of the diagnostic criteria or evaluation of autism, individuals with ASD can also present with motor difficulties.[12] Motor difficulties may be present due to:[2]

- A lack of body awareness

- Avoidance of exercise due to its social nature

- Limited strength

- Difficulty following commands and communicating

The Good News[edit | edit source]

Learning and Behavioural Difficulties[edit | edit source]

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)[edit | edit source]

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder which affects the functioning of the brain. It seems to be due to abnormalities in the dopamine system and a change in frontal lobe development.[2] While its cause is unknown, it is considered a genetic disorder, with environmental factors (e.g. diet, physical and social environments) playing a small role in its aetiology.[2][15]

The following factors can increase the risk of ADHD:[2]

- Very low birth weight

- Premature birth

- Exceptional early adversity

ADHD is diagnosed based on reported behaviours or psychiatric assessment. The primary symptoms associated with ADHD are inattentiveness, hyperactivity and impulsiveness.[2] However, fine and gross motor skills are affected in around 30 to 50 percent of children with ADHD,[2][16][17] particularly in the predominantly inattentive and combined ADHD group.[18]

These motor problems are often ignored due to behaviour difficulties, but children typically struggle with:[2]

- Dressing

- Handwriting

- Learning to ride a bicycle

- Tying shoelaces

The Good News[edit | edit source]

- Exercise can be beneficial[2][19][20][21]

- Realistic goals, attention practice, intrinsic motivation can help, as can grit and determination, locus of control and having a champion.[2]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Xcitesteps. What are developmental disabilities? Available from: http://www.xcitesteps.com/faqs/developmental-disabilities/ (accessed 9 August 2021).

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 Prowse T. The Social, Cognitive and Emotional Development of Children - Developmental Disabilities Course. Physioplus, 2021.

- ↑ Boyle CA, Boulet S, Schieve LA, Cohen RA, Blumberg SJ, Yeargin-Allsopp M et al. Trends in the prevalence of developmental disabilities in US children, 1997-2008. Pediatrics. 2011;127(6):1034-42.

- ↑ Zablotsky B, Black LI, Maenner MJ, Schieve LA, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH. Prevalence and trends of developmental disabilities among children in the United States: 2009-2017. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20190811.

- ↑ Neki NS, Chhabra A. Benign joint hypermobility syndrome. Journal of Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences. 2016; 21(1):12-8.

- ↑ Simpson MMR. Benign Joint Hypermobility Syndrome: Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Management. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2006;106(9): 531–536.

- ↑ Palmer S, Bailey S, Barker L, Barney L, Elliott A. The effectiveness of therapeutic exercise for joint hypermobility syndrome: a systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2014; 100(3): 220-7.

- ↑ Mandy W, Wang A, Lee I, Skuse D. Evaluating social (pragmatic) communication disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2017;58:1166-75.

- ↑ Norbury CF. Practitioner review: Social (pragmatic) communication disorder conceptualization, evidence and clinical implications. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55(3):204-16.

- ↑ Mayo Clinic. Autism spectrum disorder. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/autism-spectrum-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20352928 (accessed 9 August 2021).

- ↑ Crasta JE, Salzinger E, Lin MH, Gavin WJ, Davies PL. Sensory processing and attention profiles among children with sensory processing disorders and autism spectrum disorders. Front Integr Neurosci. 2020;14:22.

- ↑ Licari MK, Alvares GA, Varcin K, Evans KL, Cleary D, Reid SL et al. Prevalence of motor difficulties in autism spectrum disorder: analysis of a population-based cohort. Autism Res. 2020;13(2):298-306.

- ↑ Medscape. Autism Spectrum Disorder | Clinical Presentation. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FCejya1WWC8 [last accessed 9/8/2021]

- ↑ Bremer E, Crozier M, Lloyd M. A systematic review of the behavioural outcomes following exercise interventions for children and youth with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2016;20(8):899-915.

- ↑ Azeredo A, Moreira D, Barbosa F. ADHD, CD, and ODD: Systematic review of genetic and environmental risk factors. Res Dev Disabil. 2018;82:10-19.

- ↑ Fliers E, Rommelse N, Vermeulen SH, Altink M, Buschgens CJ, Faraone SV et al. Motor coordination problems in children and adolescents with ADHD rated by parents and teachers: effects of age and gender. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2008;115(2):211-20.

- ↑ Kaiser ML, Schoemaker MM, Albaret JM, Geuze RH. What is the evidence of impaired motor skills and motor control among children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)? Systematic review of the literature. Res Dev Disabil. 2015;36C:338-57.

- ↑ Mokobane M, Pillay BJ, Meyer A. Fine motor deficits and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in primary school children. S Afr J Psychiatr. 2019;25:1232.

- ↑ Rassovsky Y, Alfassi T. Attention improves during physical exercise in individuals with ADHD. Front Psychol. 2019;9:2747.

- ↑ Piepmeier AT, Shih CH, Whedon M, Williams LM, Davis ME, Henning DA et al. The effect of acute exercise on cognitive performance in children with and without ADHD. Journal of Sport and Health Science. 2015;4(1):97-104.

- ↑ Vysniauske R, Verburgh L, Oosterlaan J, Molendijk ML. The Effects of Physical Exercise on Functional Outcomes in the Treatment of ADHD: A Meta-Analysis. J Atten Disord. 2020;24(5):644-54.

- ↑ TED. Every kid needs a champion | Rita Pierson. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SFnMTHhKdkw [last accessed 9/8/2021]

- ↑ TED. Grit: the power of passion and perseverance | Angela Lee Duckworth. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H14bBuluwB8 [last accessed 9/8/2021]

- ↑ TED. Dr. Dean Ornish: Your genes are not your fate. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z_VdcDJAlWQ [last accessed 9/8/2021]