Dehydration

Original Editors - Jordan Dellamano Daniel McCoy from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Lydia Marie Coots, Jordan Dellamano, Daniel McCoy, Courtney Campbell, Kim Jackson, Vidya Acharya, Elaine Lonnemann, Lucinda hampton, Scott Buxton, Admin, 127.0.0.1, WikiSysop, Rachael Lowe, Tony Lowe and Wendy Walker

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Dehydration occurs when you lose more fluid than you take in, and your body doesn't have enough water and other fluids to carry out its normal functions. Young children, older adults, the ill and chronically ill are especially susceptible. Water is excreted from the body in many different forms: through urine and stool, sweating, and breathing (exhaling CO2). Dehydration symptoms generally become noticeable after 2% of one's normal water volume has been lost.[1]

Adequate hydration plays a key role in maintaining:[2]

- Circulation

- Lubrication

- Body temperature

- Lymphatic system

- Removal of waste products from the body and cells

- Facilitating ingestion and digestion

- Flushing out the urinary tract, eyes, and other organs

You can usually reverse mild to moderate dehydration by drinking more fluids, but severe dehydration needs immediate medical treatment. [3]

There are three main types of dehydration: hypotonic (primarily a loss of electrolytes), hypertonic (primarily loss of water), and isotonic (equal loss of water and electrolytes). The most commonly seen in humans is isotonic. [4]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Body water is lost through the skin, lungs, kidneys, and GI tract. The loss of body water without sodium causes dehydration.

- Water is lost from the skin, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and kidneys.

- Dehydration results when water losses from the body exceed water replacement.

- It may be caused by failure to replace obligate water losses.

There are several forms of dehydration.

- Isotonic water loss occurs when water and sodium are lost together. Causes of isotonic water loss are vomiting, diarrhea, sweating, burns, intrinsic kidney disease, hyperglycemia, and hypoaldosteronism.

- Hypertonic dehydration occurs when water losses exceed sodium losses. Serum sodium and osmolality will always be elevated in hypertonic dehydration. Excess pure water loss occurs through the skin, lungs, and kidneys. Etiologies are fever, increased respiration, and diabetes insipidus.

- Hypotonic dehydration is mostly caused by diuretics, which cause more sodium loss than water loss. Hypotonic dehydration is characterized by low sodium and osmolality.

The source of water loss relates to the etiologies of dehydration:

- Failure to replace water loss: altered mentation, immobility, impaired thirst mechanism, drug overdose leading to coma

- Excess water loss from the skin: heat, exercise, burns, severe skin diseases

- Excess water loss from the kidney: medications such as diuretics, acute and chronic renal disease, post-obstructive diuresis, salt-wasting tubular disease, Addison disease, hypoaldosteronism, hyperglycemia

- Excess water loss from the GI tract: vomiting, diarrhea, laxatives, gastric suctioning, fistulas

- Intraabdominal losses: pancreatitis, new ascites, peritonitis

- Excess insensible loss: sepsis, medications, hyperthyroidism, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), drugs[5]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

- Dehydration is most commonly found in the elderly, infants, people with fever, athletes, people living in high altitudes, and the chronically ill. Children are most affected in the first two years of their life and 2.2 million will die in this year around the world.[1]

- The elderly have an altered sense of thirst perception, changes in body water composition, and a decline in renal function as they age. Dehydration was diagnosed in 6.7% of hospitalized geriatric patients in the year 2007. In 50% of febrile cases, the patients were dehydrated and the mortality rate exceeds 50% in some studies.[6]

- Athletes also have an increased risk for dehydration due to the environment and physical exertion. This CDC web page has information about heat illness including dehydration among high school athletes.

- A study done from 2009-2012 with participants ranging from ages 6-19 years old found that inadequate hydration occurred in 54.5% of participants. Of those participants, it was found that males were at increased risk for dehydration.[7]

- In children, dehydration is at an increased risk compared to other populations due to increased metabolic rate, high incidence of infection leading to vomiting and diarrhoea (gastroenteritis), and increased body surface area compared to mass. The elderly and children have the highest risk for dehydration.[8]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Increased thirst, dry mouth, light-headedness, fatigue, impaired mental focus, low urine output, dry skin, inability to produce tears, sunken eyes are the signs of dehydration. [9]

| Mild Dehydration |

Moderate Dehydration |

Severe Dehydration |

|

|

|

Increased tiredness, headaches, nausea, and paresthesias are experienced at about 5% to 6% water loss. With 10% to 15% fluid loss, may experience symptoms of muscle cramping, dry and wrinkly skin, beginning of delirium, painful and/or decreased urine output, and decline in eyesight. Losses of water greater than 15% are usually fatal[1].

When to seek medical attention[edit | edit source]

- Constant or increased vomiting for greater than a 24 hour period

- Diarrhoea greater than two days

- Fever over 101o degrees

- Decreased urine production

- Weakness

- Confusion[11]

Diagnostic Tests[edit | edit source]

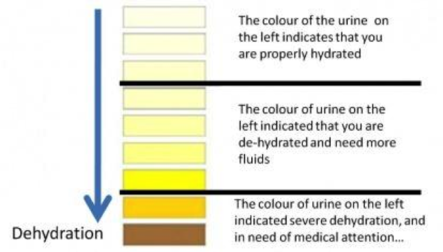

A Primary Care Physician can often diagnose dehydration based off of a person's physical signs and symptoms such as skin turgor, color of urine, low blood pressure, rapid heart rate, and sunken eyes.

To help confirm a diagnosis of dehydration and to what degree, a blood test and urinalysis may be performed.[3][12]

Blood test: can check levels of electrolytes like sodium and potassium, and how well one's kidneys are working.

Urinalysis: can show whether a person is dehydrated and to what degree, using 3 evaluation methods: visual exam, dipstick test, and microscopic exam. The dipstick test looks at acidity or pH, concentration, protein, sugar, ketones, bilirubin, evidence of infection, and blood. The microscopic exam looks at white blood cells, red blood cells, epithelial cells, bacteria or yeasts, casts, or crystals.[13]

Acute Dehydration: Weight loss of >4% of body mass within 7 days[2]

- Calculate the body weight (wt) loss

- Fluid deficit (L) = pre-illness wt – illness wt

- % dehydration = (pre-illnesses wt-illness wt)/pre-illness wt x 100%

Capillary Refill: increased time for capillary bed to refill (>2-3 seconds)[2]

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

Dehydration can cause serious systemic involvement, especially severe dehydration. Some problems that may occur include heat injury, cerebral oedema, seizures, hypovolemic shock, kidney failure, coma and death[3].

- Heat injury: Heat injury occurs most often in individuals who exercise vigorously and sweat excessively. The severity of heat injury ranges from mild heat cramps and heat exhaustion to more life-threatening heatstroke.

- Cerebral edema: This condition, also called swelling of the brain, occurs when one is trying to rehydrate. Cerebral oedema occurs when one's body tries to pull too much water back into its cells causing them to swell and rupture.

- Seizures: Seizures occur when one's electrolytes, specifically sodium and potassium, are out of balance and send mixed signals between cells. This can lead to involuntary muscle contractions and loss of consciousness.

- Hypovolemic shock: This occurs when a low blood volume causes the person's blood pressure and amount of oxygen in the body to drop. This is one of the more serious conditions that can come from dehydration. If not treated, it can become life-threatening.

- Urinary and Kidney Dysfunction: Prolonged or repeated bouts of dehydration may induce Urinary Tract Infections, kidney stones and eventually kidney failure.

- Coma and death: If severe dehydration isn't treated quickly, it can be fatal.

Differential Diagnosis [edit | edit source]

- The principle differential of dehydration in adults is the loss of body water versus the loss of blood.

- This is important because blood loss should be replaced with blood, while water loss should be replaced with fluid.

- The next point to consider is the differential diagnosis of the cause of dehydration (see Etiology above)[5]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Treatment of dehydration is aimed at rapid fluid replacement as well as identification of the cause of fluid loss. Patients with fluid deficits should be given isotonic fluid boluses tailored to the individual circumstance. Patients with more severe dehydration get larger boluses of isotonic fluid. A more careful approach is needed in elderly patients and patients with heart failure and kidney failure. In these patients, small boluses should be given, followed by frequent reassessment and additional bolus as needed.[5]

- The first goal of treatment of dehydration is to restore circulating volume. The second goal is to find the cause of the dehydration so that it will not recur.

- In patients with normal heart and renal function, liberal fluid may be given to restore volume quickly. In patients with heart failure and renal disease, volume still needs to be replaced, but a more careful approach is indicated. This is best accomplished with small volumes given quickly, followed by immediate reassessment and redosing as needed.

- In severe hyponatremia, rapid correction of volume deficits may cause a sharp rise in the serum sodium that can cause central pontine myelinolysis (CPM). The clinician must assess the risks and benefits of rapid volume repletion versus the risk of CPM. In all cases, the volume status and sodium levels must be monitored closely.[5]

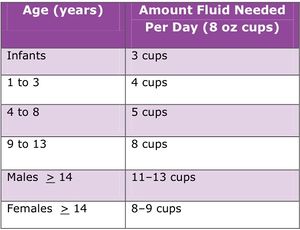

Dehydrated children need extra fluid with the right mix of water and electrolytes. Plain water, milk, soda, juice, and sports drinks don't have the right balance of water and electrolytes. What fluids to give:

- Breast milk (breast milk contains electrolytes and is the best fluid for breastfeeding babies)

- Oral rehydration solution (a combination of water and electrolytes), after the baby has gone 12 hours without vomiting, then you can give formula; give small sips of fluids every 10 minutes, then larger amounts more often if your child can keep it down.

- If severe dehydration medical personal will give fluids through a vein (by IV)[14]

Physical Therapy Management & Prevention [edit | edit source]

There is no direct physical therapy intervention for dehydration in the severe category; however, prevention and fluid replacement orally is something physical therapists can influence through patient education.

Patients should be educated about the signs and symptoms of dehydration in order to know when they may need to seek help. This is done by proper knowledge of hydration[15].

Environmental Factors[15][edit | edit source]

Heat [16]

- Being outside on a hot or humid day can cause your body to need more fluids

- It is recommended by the American Heart Association to drink water before being outdoors in the heat. This way you do not have to play catch up with Hydration when strain has already been placed on the heart.

Cold [17]

- Fluid intake also needs to be increased in cooler environments.

- Cool temperatures may blunt thirst

- Inhalation of cold, dry air increases warmth and moisture in the lungs which causes water vapor to be exhaled

- Physical Activity in the cold can increase respiratory water losses by 15-45 mL per hour

- Insulated clothing can also increase perspiration, increasing water loss

Hydration and Exercise

Before exercise: Drink 12-20oz of fluid 2 hours leading up to exercise

During Exercise:

- <1-hour drink 16-30 oz of water

- 1-3 hours drink 16-30 oz 6-8% CHO, sodium drink per hour of exercise

- >3 hours similar to guidelines for 1-3 hours but increase sodium intake

Avoid caffeine or alcohol in beverages due to their diuretic effects

Avoid hyponatremia which can occur by drinking too much fluid. therefore, diluting sodium

Monitor dehydration with changes in body weight and urine color. Each pound lost during exercise, drink 15-16oz of fluid [18]

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Dehydration: Why is it so dangerous? Rehydrate website. 2012. Available at: rehydrate.org/dehydration/index.html (Accessed April 3, 2017)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Bunn D, Hooper L, Jimoh FO, Fairweather-Trait SJ. Water-Loss dehydration and aging. Mediterranean Diet and Inflammation in the Elderly. 2013; 10.1016/j.mad.2013.11.009 http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047637413001280 (assessed 3 April 2017).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 MayoClinic. Dehydration. Mayoclinic website. 2014. Available at: http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/dehydration/DS00561. Accessed March 30, 2017.

- ↑ Dehydration-What is Dehydration?. News-medical website. Available at: http://www.news-medical.net/health/Dehydration-What-is-Dehydration.aspx. Accessed on March 30, 2017.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Taylor K, Jones EB. Adult Dehydration. InStatPearls [Internet] 2020 Mar 24. StatPearls Publishing.Available from:https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/37754/ (last accessed 18.11.2020)

- ↑ Faes MC MD et al. Dehydration in Geriatrics. Medscape website. 2007 [cited 2013 March 19] Available at:http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/567678

- ↑ Kenney EL, Long MW, Cradock AL, Gortmaker SL. Prevalence of Inadequate Hydration Among US Children and Disparities by Gender and Race/Ethnicity: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2009–2012. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105(8):e113-e118. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302572.

- ↑ Takayesu JK MD. Pediatric Dehydration. Emedicine website. 2011 [cited 2013 March 19]. Available at:http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/801012-overview

- ↑ http://survivalscoop.blogspot.com/2010/08/signs-of-dehydration-why-you-need-water.html

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Goodman, C., & Snyder, T. (2013). Differential diagnosis for physical therapists: Screening for referral. (5th edition ed., pp. 171). St. Louis, MO: Saunders.

- ↑ Dehydration-Home Treatment. WebMD Website. Available at http://www.webmd.com/fitness-exercise/tc/dehydration-home-treatment#1 (2015)Accesed March 30,2017.

- ↑ Scales K. Use of Hypodermoclysis to Manage Dehydration. Nursing Older People. 2011 [cited 2013 March 15]; 5:16-22. Available from: http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=4&sid=78597ea0-1b94-40b6-8230-44b518d28ad8%40sessionmgr111&hid=108

- ↑ Urinalysis. Mayo Clinic Web site. 2011. Available at: http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/urinalysis/MY00488/DSECTION=results. Accessed March 21, 2013.

- ↑ Dehydration Available from:https://www.msdmanuals.com/home/quick-facts-children-s-health-issues/miscellaneous-disorders-in-infants-and-young-children/dehydration-in-children

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Center for Disease Control. Dengue Clinical Case Management E-learning: Hydration Status. https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/training/cme/ccm/Hydration%20Status_F.pdf (assessed 3 April 2017)

- ↑ 20. American Heart Association. Staying Hydrated-Staying Healthy. (2014) Available at http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/HealthyLiving/PhysicalActivity/FitnessBasics/Staying-Hydrated---Staying-Healthy_UCM_441180_Article.jsp#.WOWKD5H3ahA Accessed on March 30, 2017

- ↑ Quaglio L. The Dehydration Equation. American Fitness. Winter2017. Available from: SPORTDiscuss with Full Text. Accessed on March 30,2017.

- ↑ Pariser G. Nutrition for Exercise Performance. Powerpoint Presentation Given at Bellarmine University Spring 2016.