Dehydration

Original Editors - Jordan Dellamano & Daniel McCoy from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Lydia Marie Coots, Jordan Dellamano, Daniel McCoy, Courtney Campbell, Elaine Lonnemann, Kim Jackson, Vidya Acharya, Lucinda hampton, Scott Buxton, Admin, 127.0.0.1, Rachael Lowe, Tony Lowe, Wendy Walker and WikiSysop

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Dehydration occurs when you lose more fluid than you take in, and your body doesn't have enough water and other fluids to carry out its normal functions. Young children, older adults, the ill and chronically ill are especially susceptible.

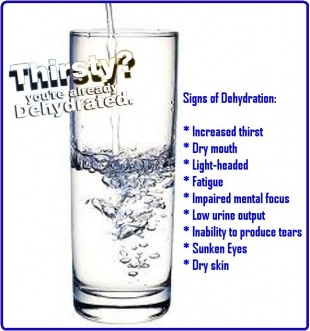

Dehydration symptoms generally become noticeable after 2% of one's normal water volume has been lost. [1]

You can usually reverse mild to moderate dehydration by drinking more fluids, but severe dehydration needs immediate medical treatment. [2]

There are three main types of dehydration: hypotonic (primarily a loss of electrolytes), hypertonic (primarily loss of water), and isotonic (equal loss of water and electrolytes). The most commonly seen in humans is isotonic. [3]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

Dehydration is most commonly found in the elderly, infants, people with fever, athletes, people living in high altitudes, and the chronically ill. Children are most affected in the first two years of their life and 2.2 million will die in this year around the world. [1]

The elderly have an altered sense of of thirst perception, changes in body water composition, and a decline in renal function as they age. Dehydration was diagnosed in 6.7% of hospitilized geriatric patients in the year 2007. In 50% of febrile cases, the patients were dehydrated and the mortality rate exceeds 50% in some studies. [4]

Athletes also have an increased risk for dehydration due to environment and physical exertion. This CDC web page has information about heat illness including dehydration among high school athletes.

In children, dehydration is at an increased risk compared to other populations due to increased metabolic rate, high incidence of infection leading to vomiting and diarrhea (gastroenteristis), and increased body surface area compared to mass. The elderly and children have the highest risk for dehydration. [5]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation [1][edit | edit source]

| Mild Dehydration |

Moderate Dehydration |

Severe Dehydration |

|

|

- At about 5% to 6% water loss, one may become groggy or sleepy, experience headaches or nausea, and may feel parasthesias.

- With 10% to 15% fluid loss, muscles may become spastic, skin may shrivel and wrinkle, vision may dim, urination will be greatly reduced and may become painful, and delirium may begin.

- Losses of greater than 15% are usually fatal.

Associated Co-morbidities [8][edit | edit source]

Physiological factors

Aged >85.

Female,

Reduced total body water.

Reduced body weight.

Altered renal function.

Reduced sensation of thirst.

Altered taste sensation and reduced appetite.

Functional factors

Reduced mobility.

Communication difficulties.

Reduced oral intake <l,500ml/day.

Poor manual dexterity.

Self-neglect,

Somnolence,

Fear of incontinence.

Fear of nocturia.

Environmental factors

Hospitalization,

Insufficient caregivers/understaffing.

Untrained carers.

Hot weather.

Overheated environment.

Isolation,

Disease-related factors

Alzheimer's disease.

Increased fluid loss, for example, diarrhea,

vomiting, fever, polyuria, wounds.

Reduced fluid intake, for example, anorexia,

dysphagia, depression, dementia, confusion,

Latrogenic factors

Laxatives, diuretics, lithium.

Dietary or fluid restrictions,

Polypharmacy: more than four medications.

Nil by mouth, for example, fasting for procedures

Medications [9][edit | edit source]

If fever is cause of dehydration, the use of:

- Acetamiminophen

- Ibuprofen

can be taken orally or as a suppository.

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values [edit | edit source]

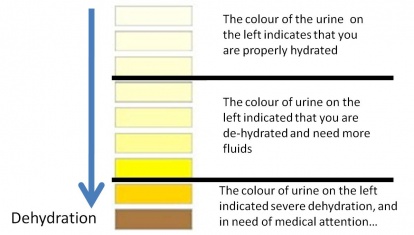

A Primary Care Physician can often diagnose dehydration based off of a person's physical signs and symptoms such as skin turgor, color of urine, low blood pressure, rapid heart rate, and sunken eyes.

To help confirm a diagnosis of dehydration and to what degree, a blood test and urinalysis may be performed.[2]

Blood test: can check levels of electrolytes like sodium and potassium, and how well one's kidneys are working.

Urinalysis: can show whether a person is dehydrated and to what degree, using 3 evaluation methods: visual exam, dipstick test, and microscopic exam. The dipstick test looks at acidity or pH, concentration, protein, sugar, ketones, bilirubin, evidence of infection, and blood. The microscopic exam looks at white blood cells, red blood cells, epithelial cells, bacteria or yeasts, casts, or crystals.[12]

Etiology/Causes [1][edit | edit source]

External/stress-related causes:

- Prolonged physical activity without consuming adequate water, especially in a hot environment

- Prolonged exposure to dry air

- Survival situations, especially desert survival conditions

- Blood loss or hypotension due to physical trauma

- Diarrhea

- Hyperthermia

- Shock

- Vomiting

Infectious Diseases:

- Cholera

- Gastroenteritis

- Shigellosis

- Yellow fever

Malnutrition:

- Electrolyte imbalance

- Hypernatremia

- Hyponatremia

- Excessive alcohol consumption

- Fasting

- Patient refusal of nutrition and hydration

Other:

- Severe hyperglycemia, as seen in Diabetes Mellitus

Systemic Involvement [2][edit | edit source]

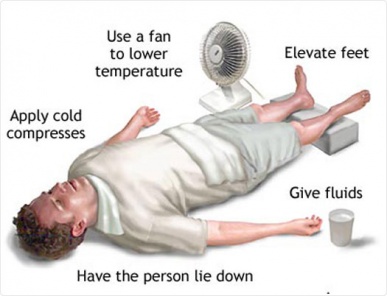

Dehydration can cause serious systemic involvement, especially severe dehydration. Some problems that may occur include: heat injury, cerebral edema, seizures, hypovolemic shock, kidney failure, coma and death.

Heat injury: Heat injury occurs most often in individuals who exercise vigorously and sweat excessively. Severity of heat injury ranges from mild heat cramps to heat exhaustion to a more life-threatening heat stroke.

Cerebral edema: This condition, also called swelling of the brain, occurs when one is trying to rehydrate. Cerebral edema occurs when one's body tries to pull too much water back into its cells causing them to swell and rupture.

Seizures: Seizures occur when one's electrolytes are out of balance and send mixed signals between cells. This can lead to involuntary muscle contractions and loss of consciousness.

Hypovolemic shock: This is one of the more serious conditions that can come from dehydration. This may happen when a low blood volume causes the person's blood pressure to drop along with a drop in the amount of oxygen in the body.

Kidney failure: This potentially life-threatening problem happens when a person's kidneys are no longer able to remove excess fluids and waste from the body.

Coma and death: If severe dehydration isn't treated quickly, it can be fatal.

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

The treatment of dehydration is best corrected with replenishment of necessary water and electrolytes. For minor dehydration, consumption of a sports drink, like Gatorade or Powerade, will be sufficient in rehydrating the body. Note: Solely drinking a sports drink for rehydration for more moderate to severe cases can cause or worsen diarrhea due to the high level of sugar.[13]

Treatment of children[2]:

- Oral rehydration solution (Pedialyte): used to treat children and infants who have diarrhea, vomiting, and fever. These solutions are made for easy digestion. Make your own ORS: mixing 1/2 teaspoon salt, 6 level teaspoons of sugar and 1 liter (about 1 quart) of safe drinking water. Be sure to measure accurately because incorrect amounts can make the solution less effective or even harmful

- Avoid certain foods and drinks: milk, sodas, caffeinated beverages, fruit juices, or gelatins can make symptoms worse.

Treatment of elderly[2]:

- Water: best for those with mild to moderate dehydration caused by diarrhea, vomiting, and fever. Other liquids like fruit juices, coffe, and soda can make diarrhea worse.

Treatment of athletes[2]:

- Cool water

- Sports drinks

- Avoid salt tablets: they can cause hypernatremic dehydration in which the body is not only short of water but is also in excess of sodium.

For more severe cases, one needs medical attention in which fluids are administered through an IV. [1]

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

There is no direct physical therapy intervention for dehydration in the severe category; however, prevention and fluid replacemant orally is something physical therapists can control. This is done by proper knowledge of hydration.

Here are some guidelines for hydration and exercise:

-Drink 12-20oz of fluid leading up to exercise

-Drink 8oz every 15 minutes during exercise

-Drink a 6-8% CHO (sports drink) for exercise >60 minutes

-Avoid caffeine or alcohol in beverages

-Each pound lost during exercise, drink 15-16oz of fluid [14]

Differential Diagnosis [16][edit | edit source]

Acidosis, Metabolic

Adrenal Insufficiency

Alkalosis, Metabolic

Bowel Obstruction in the Newborn

Burns, Thermal

Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia

Diabetes Insipidus

Diabetic Ketoacidosis

Diarrhea

Eating Disorder: Anorexia

Enteroviral Infections

Gastroenteritis

Hyperkalemia

Hypernatremia

Hypochloremic Alkalosis

Hypoglycemia

Hypokalemia

Hyponatremia

Intestinal Malrotation

Intestinal Volvulus

Intussusception

Neonatal Sepsis

Oliguria

Pyloric Stenosis, Hypertrophic

Shock

Shock and Hypotension in the Newborn

Small-Bowel Obstruction

Most differential diagnoses for dehydration have the same systemic effects. Here are links to diabetes insipidus, gastroenteritis, and diarrhea:

Case Reports/ Case Studies[edit | edit source]

Abstract

Objective: We present a case of severe dehydration, muscle cramping, and rhabdomyolysis in a high school football player followed by a suggested program for gradual return to play.

Background: A 16-year-old male football player (body mass = 69.1 kg, height = 175.3 cm) reported to the ATC after the morning

session on the second day of two-a-days complaining of severe muscle cramping.

Differential Diagnosis: The initial assessment included severe dehydration and exercise-induced muscle cramps. The differential diagnosis was severe dehydration, exertional rhabdomyolysis, or myositis. CK testing revealed elevated levels indicating mild rhabdomyolysis.

Treatment: The emergency department administered 8 L of intravenous (IV) fluid within the 48-hr hospitalization period,

followed by gradual return to activity.

Uniqueness: To our knowledge, no reports of exertional rhabdomyolysis in an adolescent football player exist. In this case, a high

school quarterback with a previous history of heat-related cramping succumbed to severe dehydration and exertional rhabdomyolysis during noncontact preseason practice. We provide suggestions for return to activity following exertional rhabdomyolysis[18].

Abstract

We investigated the level of dehydration after a match in 20 soccer players (mean ± SD, 17.9 ± 1.3 years old, height 1.75 ± 0.05 m, body mass 70.71± 7.65 kg) from two teams that participate in a Brazilian Championship game performed at a temperature of 29 ± 1.1 C and a relative humidity of 64 ± 4.2%. Body mass, urine specific gravity and urinary protein were measured before and after the match, and self-perception measurements were performed during the match. Body mass loss was 1.00 ± 0.39 kg, corresponding to a dehydration percentage of 1.35 ± 0.87%. The mean sweating rate during the match was 866 ± 319 ml · h-1 and total fluid intake was 1265.00 ± 505.45 ml. The sweating rate and the quantity of ingested fluids correlated positively (r = 0.98; P<0.05). Protein occurred in the urine in 18 soccer players. The players showed no perception of thirst and considered themselves as comfortable during the match. At the end of the match the soccer players replaced 57.7 ± 15% of the water loss and presented a condition of significant to severe dehydration based on the post-match urine specific gravity data (1.027 ± 6 g · ml-1). The results of this study demonstrate that most of the soccer players began the match with some degree of dehydration that worsened during the match[19].

Resources

[edit | edit source]

Dehydration: best practice in the care home

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=18oVtKXPw9k1l7nMNdw91bJPrzVboqaxVE7fiuMGROM6fdIwPN|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Dehydration: Why is it so dangerous? Rehydrate website. 2012. Available at: rehydrate.org/dehydration/index.html. Accessed March 15, 2013.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 MayoClinic. Dehydration. Mayoclinic website. 2011. Available at: http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/dehydration/DS00561. Accessed March 15, 2013.

- ↑ Dehydration-What is Dehydration?. News-medical website. Available at: http://www.news-medical.net/health/Dehydration-What-is-Dehydration.aspx. Accessed on March 15, 2013.

- ↑ Faes MC MD et al. Dehydration in Geriatrics. Medscape website. 2007 [cited 2013 March 19] Available at:http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/567678

- ↑ Takayesu JK MD. Pediatric Dehydration. Emedicine website. 2011 [cited 2013 March 19]. Available at:http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/801012-overview

- ↑ http://survivalscoop.blogspot.com/2010/08/signs-of-dehydration-why-you-need-water.html

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Goodman, C., & Snyder, T. (2013). Differential diagnosis for physical therapists: Screening for referral. (5th edition ed., pp. 171). St. Louis, MO: Saunders.

- ↑ Scales K. Use of Hypodermoclysis to Manage Dehydration. Nursing Older People. 2011 [cited 2013 March 15]; 5:16-22. Available from: http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=4&sid=78597ea0-1b94-40b6-8230-44b518d28ad8%40sessionmgr111&hid=108

- ↑ Dehydration. WebMD Web site. 2013. Available at: http://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/dehydration-adults?page=3. Accessed March 15, 2013.

- ↑ http://www.google.com/imgres?q=dehydration+skin+turgor&hl=en&biw=1280&bih=822&tbm=isch&tbnid=BQAE4Q1TJCIpkM:&imgrefurl=http://www.scripps.org/articles/3213-dehydration&docid=9dMCOJnDJoJJqM&imgurl=http://www.scripps.org/encyclopedia/graphics/images/en/17223.jpg&w=400&h=320&ei=MxhLUaLsHIbBygGNqICABw&zoom=1&iact=hc&vpx=2&vpy=173&dur=453&hovh=201&hovw=251&tx=85&ty=90&page=1&tbnh=136&tbnw=170&start=0&ndsp=26&ved=1t:429,r:0,s:0,i:83

- ↑ http://www.google.com/imgres?q=urine+colour+chart+dehydration&hl=en&sa=X&biw=1280&bih=822&tbm=isch&tbnid=txdT2JoMP0hAiM:&imgrefurl=http://helennutrition.blogspot.com/2012_05_01_archive.html&docid=TbVIfoUVDxmOxM&imgurl=http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-b75cuMzEbcY/T8ZYmwtowOI/AAAAAAAAAB0/R4mWy42dD38/s1600/urine%252Bchart%252Bdehydration.jpg&w=1198&h=680&ei=NRdLUaz2DKT5ygGGs4H4Bw&zoom=1&iact=hc&vpx=272&vpy=140&dur=577&hovh=169&hovw=298&tx=212&ty=104&page=1&tbnh=145&tbnw=263&start=0&ndsp=39&ved=1t:429,r:2,s:0,i:90

- ↑ Urinalysis. Mayo Clinic Web site. 2011. Available at: http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/urinalysis/MY00488/DSECTION=results. Accessed March 21, 2013.

- ↑ Vorvick L. Dehydration. National Library of Medicine NIH Web site. 2011. Available at: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000982.htm. Accessed March 21, 2013.

- ↑ Pariser G. Nutrition for Exercise Performance. Powerpoint Presentation Given at Bellarmine University April 18, 2012.

- ↑ http://www.full-timer.com/recognizing-and-treating-dehydration/

- ↑ Huang LH MD. Dehydration Differential Diagnosis. Emedicine website. 2012. [Accessed 2013 March 19] Available from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/906999-differential

- ↑ Huang LH MD. Dehydration Differential Diagnosis. Emedicine website. 2012. [Accessed 2013 March 19] Available from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/906999-differential

- ↑ Cleary M, Ruiz D et al. Dehydration, Cramping, and Exertional Rhabdomyolysis: A Case Report With Suggestions for Recovery. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation. 2007 [cited 2013 March 15]; 16: 244-259 available from: http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=efa8b8a4-607f-40fc-9b0e-7d2b4197618f%40sessionmgr10&amp;amp;amp;amp;vid=6&amp;amp;amp;amp;hid=9

- ↑ Guttierres AP et al. Dehydration for Soccer Players After a Match in the Heat. Biology of Sport. 2011 [cited 2013 March 15]; 28: 249-254. Available from: http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=d7e9bf9f-0e92-442c-8b3f-88f5823c22f0%40sessionmgr4&vid=8&hid=9