Deep Vein Thrombosis

Original Editor - Jennifer Self

Top Contributors - Admin, Karen Wilson, Kim Jackson, Laura Ritchie, Scott Buxton, Shaimaa Eldib, Jennifer Self, Lucinda hampton, Ayesha Arabi, Claire Knott, WikiSysop and Adam Vallely Farrell

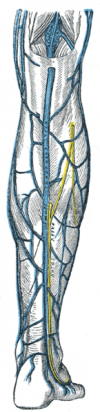

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

[edit | edit source]

Muscle veins drain into the deep veins of the lower extremity. Soleal muscle veins drain into the peroneal and tibial posterior veins. Gastrocnemius veins drain into the popliteal vein. Thrombosis usually develops as a result of venous stasis or slow-flowing blood around venous valve sinuses. Extension of the primary thrombosis occurs within or between the deep and superficial veins of the leg, and the propagating clot causes venous obstruction, damage to valves, and possible venous thromboembolism. [1]

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process

[edit | edit source]

A deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a vascular disease which consists of venous stasis and hypercoagulability in the venous system and at times can become mobile and result in a pulmonary embolus and potentially death.[2]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Clinical features of a DVT [3][edit | edit source]

- Swelling of the extremity

- Tenderness or a feeling of cramping of the calf muscles that is increased with dorsiflexion (Homan's sign)

- Inflammation and discoloration/redness of the extremity

Clinical features of a Venous Thromboembolism [4][edit | edit source]

- Calf pain and/or tenderness

- Swelling with pitting edema

- Swelling below the knee (distal deep vein thrombosis) or up to the groin (proximal deep vein thrombosis)

- Increased skin temperature

- Superficial venous dilation

- Cyanosis in patients with severe obstruction

Clinical Prediction Rule, developed by Wells and Colleagues

[edit | edit source]

The following clinical prediction rule can help a clinician identify a DVT. [5][6]

- Active cancer (treatment ongoing, within previous 6 months, or palliative)= 1 point

- Paralysis, paresis, or recent plaster immobilization of the lower extremities= 1 point

- Recently bedridden for > 3 days or major surgery within 4 weeks= 1 point

- Localized tenderness along thte distribution of the deep venous system. Tenderness along the deep venous system is assessed by firm palpation in the cneter of the posterior calf, the popliteal space, and along the area of the femoral vein in the anterior thigh and groin= 1 point

- Entire lower extremity swelling= 1 point

- Calf swelling > 3 cm when compared with the asymptomatic lower extremity. Measured with a tape measure 10cm below the tibial tuberosity= 1 point

- Pitting edema (greater in the symptomatic lower extremity)= 1 point

- Collateral superficial veins (nonvaricose)= 1 point

- Alternative diagnosis as likely or greater than that of proximal DVT. More common alternative diagnoses are cellulitis, calf strain, Baker Cyst, or postoperative swelling= -2 points

The total score for all items is tallied and the probability of the patients having a DVT are as follows:

0= low, 1-2=moderate,and ≥3=high[5]

Diagnostic Procedures

[edit | edit source]

The is a continuing search for a DVT screening test which can be used quickly to rule-out a DVT to reduce the need for imaging. A fast, reliable, non-invasive, and inexpensive screening test is needed that can be performed immediately on attendance at hospital.

Clinical diagnosis is usually unreliable and this is a problem when needing that quick test to rule out a DVT, screening is the best you can achieve before a definitive diagnosis is usually discovered by ultrasonography or venography[7].

Homans' Sign[edit | edit source]

| [8] |

The patient's foot is passively dorsiflexed with the knee extended. Pain in the calf indicates a positive Homans' sign for DVT. Tenderness is also elicited upon palpation of the calf.[9]

D-Dimer testing[edit | edit source]

A simple blood test of fibrin degradation. D-dimer levels in the blood are increased by any condition that produces fibrin; this testing has been found to be the most useful blood marker of fibrinolysis. The negative likelihood ratio is higher than 99%. This test is best used on outpatients with a low probability of PDVT, based on the use of the CDR by Wells & colleagues.[6]

Compression ultrasound/Duplex Ultrasound[edit | edit source]

This is a diagnostic procedure involving the use of a 3-7.5 MHz transducer to produce an image of the involved vein. This is considered to be the first-choice diagnostic test for patients with symptomatic PDVT in the moderate to high probability groups, based on the use of the CDR by Wells & colleagues. Sensitivity and specificity for compression ultrasonography average 95% for detection fo PDVT.[6]

Venography[edit | edit source]

This is considered the gold standard test for PDVT, but this test is invasive and carries some risk. This procedure involves an x-ray of the veins (venogram) taken after a special dye is injected into the bone marrow or veins.[6]

Management / Interventions

[edit | edit source]

Anticoagulation[edit | edit source]

Anticoagulation is the usual treatment for DVT. Patients are generally initiated on a brief course (i.e., less than a week) of heparin treatment while they start on a 3-6 month course of warfarin (or related vitamin K inhibitors).[12] Once the thrombosis is treated with RBC-thinning agents, the affected area has a fair chance of returning to its normal proportions. However, thinning agents do not lessen the chance of embolism to the pulmonary or coronary arteries.[13]

Thrombolysis[edit | edit source]

Thrombolysis is generally used for an extensive clot. Although a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials by the Cochrane Collaboration shows improved outcomes with thrombolysis, there may be an increase in serious bleeding complications.[14]

Compression stockings[edit | edit source]

Elastic compression stockings should be routinely applied "beginning within 1 month of diagnosis of proximal DVT and continuing for a minimum of 1 year after diagnosis".[15]

Inferior Vena Cava filter[edit | edit source]

IVC filter may prevent pulmonary embolisation and is an option for patients with an absolute contraindiciation to anticoagulant treatment.[16]

Differential Diagnosis

[edit | edit source]

Potential causes for calf pain:[17]

- Pyomyositis

- Fibula shaft fracture

- Deep vein thrombosis

- Hematoma

- Rupture of Achilles Tendon

- Soleus muscle strain

- Acute posterior compartment syndrome

- Muscle cramps

Resources

[edit | edit source]

Presentations[edit | edit source]

|

Differential Diagnosis and VTE

This presentation, created by Carleen Jogodka as part of the Evidence In Motion OMPT Fellowship, discusses differential diagnosis for venous thromboembolism. |

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1lGTpA7S74wiuMUQ_tI6X1P9s02KQ2A3QIj_uTEdGv29exlk3C|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Dutton. Orthopaedic Examination, Evaluation, and Intervention. McGraw Hill; 2004. pg 261, 1338, 1367.

- ↑ Pecina MM, Bojanic I. Overuse Injuries of the Musculoskeletal System. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1993.

- ↑ Dutton. Orthopaedic Examination, Evaluation, and Intervention. McGraw Hill; 2004. pg 261, 1338, 1367.

- ↑ Dutton. Orthopaedic Examination, Evaluation, and Intervention. McGraw Hill; 2004. pg 261, 1338, 1367.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Greenfield B, Tovin B. Knee. Current Concepts in Orthopaedic Physical Therapy. La Crosse: Orthopaedic Section, American Physical Therapy Association; 2001.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Riddle DL, Wells PS. Diagnosis of Lower-Extremity Deep Vein Thrombosis in Outpatients. Physical Therapy. 84 (8); 729-735.

- ↑ Tovey, C. Wyatt S. Diagnosis, investigation, and management of deep vein thrombosis. BMJ VOLUME 326 31 MAY 2003 1180-1184

- ↑ bigesor. Homan's Sign. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2cp2DikKRwg [last accessed 28/03/13]

- ↑ Magee D. Orthopedic Physical Assessment, 4th ed. Elsevier Sciences. 2006; pg 808.

- ↑ Goodacre S, Sutton A, Sampson F. Meta-Analysis: The Value of Clinical Assessment in the Diagnosis of Deep Venous Thrombosis. Annals of Internal Medicine. July 2005: 143(2); 2129-139.

- ↑ Goodacre S, Sutton A, Sampson F. Meta-Analysis: The Value of Clinical Assessment in the Diagnosis of Deep Venous Thrombosis. Annals of Internal Medicine. July 2005: 143(2); 2129-139.

- ↑ Snow V, Qaseem A, Barry P, et al. (2007). "Management of venous thromboembolism: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians". Ann. Intern. Med. 146 (3): 204–10.

- ↑ Palareti G, Cosmi B, Legnani C, et al. (2006). "D-dimer testing to determine the duration of anticoagulation therapy". N. Engl. J. Med. 355 (17): 1780–9

- ↑ Watson L, Armon M (2004). "Thrombolysis for acute deep vein thrombosis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD002783

- ↑ Snow V, Qaseem A, Barry P, et al. (2007). "Management of venous thromboembolism: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians". Ann. Intern. Med. 146 (3): 204–10.

- ↑ Decousus H, Leizorovicz A, Parent F, Page Y, Tardy B, Girard P, Laporte S, Faivre R, Charbonnier B, Barral F, Huet Y, Simonneau G (1998). "A clinical trial of vena caval filters in the prevention of pulmonary embolism in patients with proximal deep-vein thrombosis. Prévention du Risque d'Embolie Pulmonaire par Interruption Cave Study Group". N Engl J Med 338 (7): 409–15.

- ↑ Dutton. Orthopaedic Examination, Evaluation, and Intervention. McGraw Hill; 2004. pg 261, 1338, 1367.