Cubital Tunnel Syndrome: Difference between revisions

Lindsey Katt (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Lindsey Katt (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

In order to properly diagnose cubital tunnel syndrome a skilled physical therapist must conduct a proper physical examination including; sensory changes in the ulnar nerve distribution (ulnar ½ of the 4th digit and entirety of the 5th), vague pain, atrophy of the intrinsic muscles innervated by the ulnar nerve, a neural provocation test of the ulnar nerve, and sparing of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle.<ref name="Boucher">Boucher B, Wainner R, Robertson E. Common disorders of the elbow-forearm complex: part II. Paper presented at: Texas State University DPT PT7559 Lecture; October 13, 2010; San Marcos, TX.</ref> Patients with this diagnosis will also present with a positive Elbow Flexion Test and a positive Tinel test. These special tests are detailed below. Not only is the examination vital to ruling in a correct diagnosis, it allows the practitioner to properly rule out those with similar presentations. | In order to properly diagnose cubital tunnel syndrome a skilled physical therapist must conduct a proper physical examination including; sensory changes in the ulnar nerve distribution (ulnar ½ of the 4th digit and entirety of the 5th), vague pain, atrophy of the intrinsic muscles innervated by the ulnar nerve, a neural provocation test of the ulnar nerve, and sparing of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle.<ref name="Boucher">Boucher B, Wainner R, Robertson E. Common disorders of the elbow-forearm complex: part II. Paper presented at: Texas State University DPT PT7559 Lecture; October 13, 2010; San Marcos, TX.</ref> Patients with this diagnosis will also present with a positive Elbow Flexion Test and a positive Tinel test. These special tests are detailed below. Not only is the examination vital to ruling in a correct diagnosis, it allows the practitioner to properly rule out those with similar presentations. | ||

<br><u>The Elbow Flexion Test</u>: Typically performed bilaterally with the shoulder in full external rotation and the elbow actively held in sustained maximal flexion for 1 minute with the wrist kept in neutral.<ref name="Coppieters" /> Symptoms are produced because maximal elbow flexion reduces the cubital tunnel volume by approximately 55% causing increased neural pressure on the ulnar nerve.<ref name="Kuschner" /> Some studies state this test can include additional components such as wrist extension and wrist flexion or sustained maximal elbow flexion for up to 3 minutes.<ref name="Kuschner" /> Note, these studies also state that quicker signs of a positive test are more indicative of a true diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome. A positive test is reproduction of pain at the medial aspect of the elbow and numbness and tingling in the ulnar distribution on the involved side. This test has a high positive predictive value (0.97), indicating a high probability of cubital tunnel syndrome if positive. Specificity (0.99) Sensitivity (0.75).<ref name="Behr">Behr CT, Altchek DW. The elbow. Clin Sports Med. 1997;16:681-704.</ref> | <br><u>The Elbow Flexion Test</u>: Typically performed bilaterally with the shoulder in full external rotation and the elbow actively held in sustained maximal flexion for 1 minute with the wrist kept in neutral.<ref name="Coppieters" /> Symptoms are produced because maximal elbow flexion reduces the cubital tunnel volume by approximately 55% causing increased neural pressure on the ulnar nerve.<ref name="Kuschner" /> Some studies state this test can include additional components such as wrist extension and wrist flexion or sustained maximal elbow flexion for up to 3 minutes.<ref name="Kuschner" /> Note, these studies also state that quicker signs of a positive test are more indicative of a true diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome. A positive test is reproduction of pain at the medial aspect of the elbow and numbness and tingling in the ulnar distribution on the involved side. This test has a high positive predictive value (0.97), indicating a high probability of cubital tunnel syndrome if positive. Specificity (0.99) Sensitivity (0.75).<ref name="Behr">Behr CT, Altchek DW. The elbow. Clin Sports Med. 1997;16:681-704.</ref> | ||

{{#ev:youtube|gBY1w82J9KI|300}} <br> | {{#ev:youtube|gBY1w82J9KI|300}} <br> | ||

<u>Tinel Sign</u>: After locating the ulnar groove, posterior to the medial epicondyle of the humerus, the clinician will proceed with percussions (tapping) of the ulnar nerve as it passes through the cubital tunnel.<ref name="Coppieters" /><ref name="Kuschner" /> The number of percussions will vary depending on the research, but four to six taps should be sufficient to elicit symptoms. A positive test is the reproduction of tingling and numbness in the ulnar nerve distribution on the involved side. Practitioners must be cautious with the interpretation of the test because it has been found positive in 24% of asymptomatic subjects and it could be negative for those in the advanced stage of the diagnosis because the nerve is no longer regenerating. Specificity (0.98) Sensitivity (0.70).<ref name="Novak">Novak CB, Lee GW, Mackinnon SE, Lay L. Provacative testing for cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 1994;19:817-820.</ref> | <u>Tinel Sign</u>: After locating the ulnar groove, posterior to the medial epicondyle of the humerus, the clinician will proceed with percussions (tapping) of the ulnar nerve as it passes through the cubital tunnel.<ref name="Coppieters" /><ref name="Kuschner" /> The number of percussions will vary depending on the research, but four to six taps should be sufficient to elicit symptoms. A positive test is the reproduction of tingling and numbness in the ulnar nerve distribution on the involved side. Practitioners must be cautious with the interpretation of the test because it has been found positive in 24% of asymptomatic subjects and it could be negative for those in the advanced stage of the diagnosis because the nerve is no longer regenerating. Specificity (0.98) Sensitivity (0.70).<ref name="Novak">Novak CB, Lee GW, Mackinnon SE, Lay L. Provacative testing for cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 1994;19:817-820.</ref> | ||

{{#ev:youtube|T1oFeckmaGQ|300}} | {{#ev:youtube|T1oFeckmaGQ|300}} | ||

<u>The Pressure Provocative Test</u>: The clinician applies pressure at the ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel with the UE positioned as in the elbow flexion test for 30 seconds. Sensitivity (0.91).<ref name="Novak" /><br> {{#ev:youtube|2DH3ZVo4b90|300}} | <u>The Pressure Provocative Test</u>: The clinician applies pressure at the ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel with the UE positioned as in the elbow flexion test for 30 seconds. Sensitivity (0.91).<ref name="Novak" /><br> | ||

{{#ev:youtube|2DH3ZVo4b90|300}} | |||

== Medical Management (current best evidence) == | == Medical Management (current best evidence) == | ||

Revision as of 00:36, 23 November 2010

Original Editors

Lead Editors - Your name will be added here if you are a lead editor on this page. Read more.

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

Databases: CINAHL, Cochrane, Medline with Full Text, PubMed, ScienceDirect, GoogleScholar, EBSCO, ProQuest

Search Terms: cubital tunnel syndrome, ulnar nerve entrapment, compression, medial elbow pain, ulnar elbow pain, nerve entrapment, ulnar nerve, surgery, conservative treatment, rehabilitation, compression injury of upper extremity, coppieters, anterior transposition of ulnar nerve, ulnar nerve decompression, tardy ulnar neuritis, ulnar nerve glide, osborne, neurodynamics

Search Timeline: September 19, 2010 – November 22, 2010

Definition/Description

[edit | edit source]

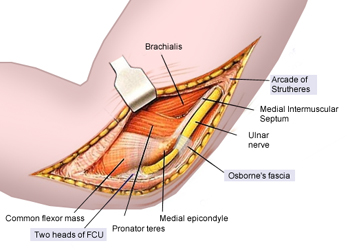

Cubital tunnel syndrome (CBTS) is a progressive entrapment neuropathy of the ulnar nerve at the medial aspect of the elbow. The ulnar nerve, which is a motor and sensory nerve, is formed from the medial cord of the brachial plexus, which originates from nerve roots C8 and T1.[1][2][3] The ulnar nerve travels down the posterior aspect of the arm to eventually traverse posterior to the medial epicondyle through an area known as the cubital tunnel. The cubital tunnel extends from the medial epicondyle of the humerus to the olecranon process of the ulna.[4] The nerve runs superficial to the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) and deep to the aponeurotic attachment of the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU), which is also known as Osborne’s ligament. Once the ulnar nerve reaches the proximal border of Osborne’s ligament it is located in the cubital tunnel.

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Cubital tunnel syndrome is the second most commonly reported upper extremity entrapment neuropathy and is the most common ulnar nerve neuropathy.[5][6] Risk factors include: head injuries with upper extremity flexion contractures, age > 40, overhead throwers, work that involves prolonged periods of elbow flexion such as holding a telephone, and resting elbows on a hard surface.[3][7][8] Entrapment can occur at multiple levels in the cubital tunnel including: the Arcade of Struthers, the medial intermuscular septum, the medial epicondyle, Osborne's ligament and the flexor-pronator aponeurosis.[9] It may be a result of direct or indirect trauma and is vulnerable to traction, friction, and compression. Traction injuries may be the result of longstanding valgus deformity and flexion contractures, but are most common in throwers due to extreme valgus stress placed on the arm.[10] Compression of the nerve at the cubital tunnel may occur due to reactive changes at the UCL, adhesions within the tunnel, hypertrophy of the surrounding musculature, or joint changes.

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

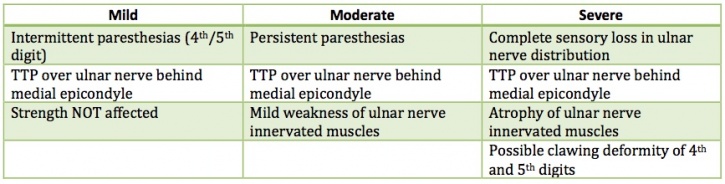

Depending on the duration and progression of the disorder, patients with cubital tunnel syndrome will present with similar but specific symptoms (see Table 1).[5] The most common complaint for any cubital tunnel syndrome patient is paresthesias in the 4th and 5th digits that often wakes them at night.[3] The patient may also report non-painful "snapping" or "popping" during active and passive flexion and extension of the elbow and a Wartenberg sign (abduction of the fifth digit due to weakness of the third palmar interosseous muscle) may also be present. Patients may also notice weakness while pinching, occasional clumsiness, and a tendency to drop things.[11]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Differential diagnosis should include but are not limited to:[3][12][13]

- Cervical Radiculopathy C8-T1 – Motor and sensory deficits in a dermatomal pattern including 4th-5th digits, associated weakness of intrinsic muscles of the hand, and associated painful and often limited cervical range of motion.

- Thoracic Outlet Syndrome – Compression of the structures of the brachial plexus potentially leading to pain, paresthesias, and weakness in arm, shoulder, and neck.[14]

- UCL Insufficiency – Abnormal growth of tissue on the apex of the lung causing compression of the lower trunk of the brachial plexus.

- Pancoast Tumor - Abnormal growth of tissue on the apex of the lung causing compression of the lower trunk of the brachial plexus.

These diagnoses present similarly to cubital tunnel with pain, paresthesias, and potential weakness; however, specific symptoms to each diagnosis allows the practitioner to rule out the doppelganger and rule in cubital tunnel syndrome, such as limited cervical motion and paresthesias in other areas outside the ulnar nerve distribution. It is important for clinicians to correctly identify this diagnosis, as earlier identification has shown an 88% improvement rate when treated within one year of onset as opposed to 67% improvement if treated after one year.[3][15]

Examination[edit | edit source]

In order to properly diagnose cubital tunnel syndrome a skilled physical therapist must conduct a proper physical examination including; sensory changes in the ulnar nerve distribution (ulnar ½ of the 4th digit and entirety of the 5th), vague pain, atrophy of the intrinsic muscles innervated by the ulnar nerve, a neural provocation test of the ulnar nerve, and sparing of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle.[16] Patients with this diagnosis will also present with a positive Elbow Flexion Test and a positive Tinel test. These special tests are detailed below. Not only is the examination vital to ruling in a correct diagnosis, it allows the practitioner to properly rule out those with similar presentations.

The Elbow Flexion Test: Typically performed bilaterally with the shoulder in full external rotation and the elbow actively held in sustained maximal flexion for 1 minute with the wrist kept in neutral.[5] Symptoms are produced because maximal elbow flexion reduces the cubital tunnel volume by approximately 55% causing increased neural pressure on the ulnar nerve.[6] Some studies state this test can include additional components such as wrist extension and wrist flexion or sustained maximal elbow flexion for up to 3 minutes.[6] Note, these studies also state that quicker signs of a positive test are more indicative of a true diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome. A positive test is reproduction of pain at the medial aspect of the elbow and numbness and tingling in the ulnar distribution on the involved side. This test has a high positive predictive value (0.97), indicating a high probability of cubital tunnel syndrome if positive. Specificity (0.99) Sensitivity (0.75).[17]

Tinel Sign: After locating the ulnar groove, posterior to the medial epicondyle of the humerus, the clinician will proceed with percussions (tapping) of the ulnar nerve as it passes through the cubital tunnel.[5][6] The number of percussions will vary depending on the research, but four to six taps should be sufficient to elicit symptoms. A positive test is the reproduction of tingling and numbness in the ulnar nerve distribution on the involved side. Practitioners must be cautious with the interpretation of the test because it has been found positive in 24% of asymptomatic subjects and it could be negative for those in the advanced stage of the diagnosis because the nerve is no longer regenerating. Specificity (0.98) Sensitivity (0.70).[18]

The Pressure Provocative Test: The clinician applies pressure at the ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel with the UE positioned as in the elbow flexion test for 30 seconds. Sensitivity (0.91).[18]

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

add text here

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

add text here

Key Research[edit | edit source]

add links and reviews of high quality evidence here (case studies should be added on new pages using the case study template)

Resources

[edit | edit source]

add appropriate resources here

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

With CBTS being the most common ulnar nerve neuropathy and the 2nd most common upper extremity neuropathy, early detection through proper differential diagnosis is key to ensuring best possible patient outcomes. As skilled clinicians we must tailor our treatment to each patient, post-surgical or not, in a manner that follows surgeon precautions if necessary and aims to normalize the sensitivity of the nerve, restore normal nerve biomechanics, and restores or prevents secondary complications. With insufficient quality evidence to support conservative management of cubital tunnel syndrome, we need more randomized controlled trials to determine the effectiveness of current treatment trends.

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

see tutorial on Adding PubMed Feed

Extension:RSS -- Error: Not a valid URL: Feed goes here!!|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ Feindel W, Stratford J. Cubital tunnel compression in tardy ulnar nerve palsy. Can Med Assoc J. 1958;78:351.

- ↑ Osborne GV. The surgical treatment of tardy ulnar neuritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1957;39B:782.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Tetro AM, Pichora DR. Cubital tunnel syndrome and the painful upper extremity. Hand Clin. 1996;12(4):665-677.

- ↑ Wheeless CR. Cubital tunnel syndrome. http://www.wheelessonline.com/ortho/cubital_tunnel_syndrome. Updated June 5, 2010. Accessed November 1, 2010.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Coppieters MW, Bartholomeeusen KE, Stappaerts KH. Incorporating nerve-gliding techniques in the conservative treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2004;27(9):560-568.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Kuschner SH, Ebramzadeh E, Mitchell S. Evaluation of elbow flexion and tinel tests for cubital tunnel syndrome in asymptomatic individuals. Orthopedics. 2006;29(4):305-308.

- ↑ Bartels RHMA, Verbeek ALM. Risk factors for ulnar nerve compression at the elbow: a case control study. Acta Neurochir Wien. 2007;149:669-674.

- ↑ Oskay D, Meriç A, Kirdi N, Firat T, Ayhan Ç, Leblebicioglu G. Neurodynamic mobilization in the conservative treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome: long-term follow-up of 7 cases. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2010;33(2):156-163.

- ↑ Husain SN, Kaufmann RA. The diagnosis and treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. Current Orthopaedic Practice. 2008;19(5):470-474.

- ↑ Lee ML, Rosenwasser MP. Chronic elbow instability. Orthop Coin North Am. 1999;30:81-89.

- ↑ ASSH. Cubital Tunnel Syndrome. http://www.assh.org/Public/HandConditions/Pages/CubitalTunnelSyndrome.aspx. Accessed November 1, 2010.

- ↑ Galarza M, Gazzeri R, Gazzeri G, Zuccarello M, Taha J. Cubital tunnel surgery in patients with cervical radiculopathy: double crush syndrome?. Neurosurg Rev. 2009;32(4):471-478.

- ↑ Lund AT, Amadio PC. Treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome: perspectives for the therapist. J Hand Ther. 2006;19:170-179.

- ↑ Office of Communications and Public Liaison. NINDS Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Information Page. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/thoracic/thoracic.htm. Updated July 14, 2010. Accessed November 1, 2010.

- ↑ Chan RC, Paine KWE, Varughese G. Ulnar neuropathy at the elbow: comparison of simple decompression and anterior transfer. Neurosurgery. 1980;7:545-550.

- ↑ Boucher B, Wainner R, Robertson E. Common disorders of the elbow-forearm complex: part II. Paper presented at: Texas State University DPT PT7559 Lecture; October 13, 2010; San Marcos, TX.

- ↑ Behr CT, Altchek DW. The elbow. Clin Sports Med. 1997;16:681-704.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Novak CB, Lee GW, Mackinnon SE, Lay L. Provacative testing for cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 1994;19:817-820.