Concussion Treatment: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Kim Jackson (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (26 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | <div class="editorbox"> | ||

'''Original Editor '''- Megyn Robertson | '''Original Editor '''- Megyn Robertson | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Using Vestibular/Ocular-Motor Screening (VOMS)as Treatment == | |||

Exercise approaches to alleviate symptoms of vestibular hypofunction can be divided into two categories – namely adaptation or habituation exercises. | == Concussion == | ||

Concussions can cause a host of variety of structural and physical impairments. Interventions for concussions need to be geared towards the patient's dysfunction as symptom presentations will differ among patients. <ref>Jabali MM, Alhakami AM, Qasheesh MA, Uddin S. [https://www.sjosm.org/article.asp?issn=1319-6308;year=2020;volume=20;issue=2;spage=31;epage=35;aulast=Jabali Efficacy of physical therapy intervention in sports-related concussion among young individuals age-group–A narrative review.] Saudi Journal of Sports Medicine. 2020 May 1;20(2):31.</ref><ref>Lempke L, Jaffri A, Erdman N. [https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/jsr/28/1/article-p99.xml The effects of early physical activity compared to early physical rest on concussion symptoms]. Journal of sport rehabilitation. 2019 Jan 1;28(1):99-105.</ref> | |||

Physical therapists interventions that may be included in concussive patients include, communication/education and addressing movement-related impairments, vestibular-oculomotor impairment and aerobic exercise as tolerated.<ref>Quatman-Yates, Catherine C., Airelle Hunter-Giordano, Kathy K. Shimamura, Rob Landel, Bara A. Alsalaheen, Timothy A. Hanke, Karen L. McCulloch et al. "[https://www.jospt.org/doi/10.2519/jospt.2020.0301 Physical therapy evaluation and treatment after concussion/mild traumatic brain injury: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health] from the academy of orthopaedic physical therapy, American Academy of sports physical therapy, academy of neurologic physical therapy, and academy of pediatric physical therapy of the American Physical therapy association." ''Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy'' 50, no. 4 (2020): CPG1-CPG73.</ref> | |||

== Using Vestibular/Ocular-Motor Screening (VOMS) as Treatment == | |||

Research shows that 60% of concussive patients have vestibular/ocular-motor symptoms.<ref>Moser RS, Schatz P, Mayer B, Friedman S, Perkins M, Zebrowski C, Islam S, Lemke H, James M, Vidal P. [https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/20597002211020896 Does time since injury and duration matter in the benefits of physical therapy treatment for concussion]?. Journal of Concussion. 2021 Jun;5:20597002211020896.</ref> Exercise approaches to alleviate symptoms of vestibular hypofunction can be divided into two categories – namely adaptation or habituation exercises. Both exercise interventions lead to a reduction in the self-report measure of the impact of symptoms on the ability to function, a decrease in the sensitivity to movements, and an improvement in the ability to see clearly during head movements. | |||

=== Habituation === | === Habituation === | ||

Habituation exercises are given to patients who have certain types of inner ear disorders such as dizziness when they move their heads in certain ways. Habituation exercises are based on the idea that repeated exposure to a provocative stimulus (e.g. head movements) will lead to a reduction of the motion-provoked symptoms.<ref>Shepard NT, Telian SA, Smith-Wheelock M, Raj A. Vestibular and balance rehabilitation therapy. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology 1993;102(3 Pt 1):198–205.</ref><ref>Telian SA, Shepard NT, Smith-Wheelock M, Kemink JL. Habituation therapy for chronic vestibular dysfunction: preliminary results. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;103(1):89–95. </ref> | Habituation exercises are given to patients who have certain types of inner ear disorders such as dizziness when they move their heads in certain ways. Habituation exercises are based on the idea that repeated exposure to a provocative stimulus (e.g. head movements) will lead to a reduction of the motion-provoked symptoms.<ref>Shepard NT, Telian SA, Smith-Wheelock M, Raj A. [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Neil_Shepard/publication/14742432_Vestibular_and_Balance_Rehabilitation_Therapy/links/58a488dca6fdcc0e0759cb5c/Vestibular-and-Balance-Rehabilitation-Therapy.pdf Vestibular and balance rehabilitation therapy.] Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology 1993;102(3 Pt 1):198–205.</ref><ref>Telian SA, Shepard NT, Smith-Wheelock M, Kemink JL. [https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/019459989010300113 Habituation therapy for chronic vestibular dysfunction: preliminary results]. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;103(1):89–95. </ref> This change is thought to be due to long-term changes within the nervous system, and there is clinical evidence indicating that the habituation exercises can lead to long-term changes in symptoms.<ref>Clement G, Tilikete C, Courjon JH. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00221-008-1471-0 Retention of habituation of vestibulo-ocular reflex and sensation of rotation in humans.] Exp Brain Res 2008 Sep;190(3):307–315.</ref> The actual neural mechanism behind the effectiveness of the habituation exercises is not understood. Patients who perform habituation exercises will have a greater reduction in their motion sensitivity. | ||

=== Adaptation === | === Adaptation === | ||

Adaptation exercises or gaze stability exercises are used to modify the magnitude of the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) in response to a given input (head movement). One of the signals that induces adaptation of the VOR is retinal slip combined with head movement.<ref>Shelhamer M, Tiliket C, Roberts D, Kramer PD, Zee DS. Short-term vestibulo-ocular reflex adaptation in humans. II. Error signals. Exp Brain Res. 1994;100(2):328–336. </ref>. This is the basis for what has traditionally been considered adaptation exercises. These exercises require the individual to perform rapid, active head rotations while watching a visual target, with the stipulation that the target remains in focus during the head movements.<ref>Herdman SJ. Exercise strategies for vestibular disorders. Ear Nose Throat J 1989;68(12):961–964. </ref>If the target is stationary, then the exercises are referred to as x1 viewing exercises. If the target is moving in the opposite direction of the head movement, then these exercises are referred to as x2 viewing exercises. While these exercises have been shown to improve dynamic visual acuity, the actual mechanism behind this improvement is not known.<ref>Herdman SJ, Schubert MC, Das VE, Tusa RJ. Recovery of dynamic visual acuity in unilateral vestibular hypofunction. Arch.Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003;129(8):819–824. </ref> | Adaptation exercises or gaze stability exercises are used to modify the magnitude of the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) in response to a given input (head movement)<ref name=":4">Roller RA, Hall CD. [https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-vestibular-research/ves633 A speed-based approach to vestibular rehabilitation for peripheral vestibular hypofunction: A retrospective chart review.] Journal of Vestibular Research. 2018 Jan 1;28(3-4):349-57.</ref>. One of the signals that induces adaptation of the VOR is retinal slip combined with head movement.<ref>Shelhamer M, Tiliket C, Roberts D, Kramer PD, Zee DS. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00227202 Short-term vestibulo-ocular reflex adaptation in humans.] II. Error signals. Exp Brain Res. 1994;100(2):328–336. </ref>. This is the basis for what has traditionally been considered adaptation exercises. These exercises require the individual to perform rapid, active head rotations while watching a visual target, with the stipulation that the target remains in focus during the head movements.<ref name=":4" /><ref>Herdman SJ. [https://europepmc.org/abstract/med/2620646 Exercise strategies for vestibular disorders]. Ear Nose Throat J 1989;68(12):961–964. </ref> If the target is stationary, then the exercises are referred to as x1 viewing exercises. If the target is moving in the opposite direction of the head movement, then these exercises are referred to as x2 viewing exercises. While these exercises have been shown to improve dynamic visual acuity, the actual mechanism behind this improvement is not known.<ref>Herdman SJ, Schubert MC, Das VE, Tusa RJ. [https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaneurology/fullarticle/483931 Recovery of dynamic visual acuity in unilateral vestibular hypofunction.] Arch.Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003;129(8):819–824. </ref>Patients who perform gaze stability exercises will improve their dynamic visual acuity. | ||

Patients who perform gaze stability exercises will improve their dynamic visual acuity | |||

== VOMS Treatment == | == VOMS Treatment == | ||

In a nutshell, take what | In a nutshell, take what exacerbates patient symptoms and use that as your rehabilitation programme. Ease the patient into it, using graded exposure, until the patient is able to perform the activity without symptom exacerbation. Generally it is accepted to incorporate both habituation and adaptation in treatment regimes. Clendaniel<ref name=":0">Clendaniel RA . [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2904475/ The effects of habituation and gaze-stability exercises in the treatment of unilateral vestibular hypofunction – preliminary results]. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2010;34(2): 111–116. </ref> outlines an example of a home programme below with progressions. You can change the base of support and surfaces (stable to unstable) in conjunction with the VOMS progressions. You can also change the environment from quiet and low light to noisy and bright light as the patient tolerates for additional sensory load/input. | ||

Exercise Progression<ref name=":0" /> | '''Exercise Progression'''<ref name=":0" /> | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

!'''Gaze-Stabilization Exercises''' | !'''Gaze-Stabilization Exercises''' | ||

| Line 55: | Line 57: | ||

|Large amplitude, rapid horizontal and vertical cervical rotation (standing), standing pivots (180 degrees), seated trunk flexion-extension, and Brandt- Daroff exercise 3 sets of 5 cycles | |Large amplitude, rapid horizontal and vertical cervical rotation (standing), standing pivots (180 degrees), seated trunk flexion-extension, and Brandt- Daroff exercise 3 sets of 5 cycles | ||

|} | |} | ||

''Figure 1: Habituation and Adaptation progressions (Clendaniel,2010)'' | |||

== Medication == | == Medication == | ||

Data demonstrate that preventing an inflammatory response (through the use of non-steroidal anti inflammatories) to a concussion is not a viable treatment, despite its effectiveness in treating other traumatic injuries occurring in the CNS. The evidence suggests that the concussed brain presents a unique inflammatory signature as opposed to a general inflammatory response that occurs following any CNS injury.<ref>Patterson ZR &Holahan MR. Understanding the neuroinflammatory response following concussion to develop treatment strategies. Review Article. Front. Cell. Neurosci.12 December 2012 </ref> There is no effective medicinal treatment for a concussion to date. | Data demonstrate that preventing an inflammatory response (through the use of non-steroidal anti inflammatories) to a concussion is not a viable treatment, despite its effectiveness in treating other traumatic injuries occurring in the CNS. The evidence suggests that the concussed brain presents a unique inflammatory signature as opposed to a general inflammatory response that occurs following any CNS injury.<ref>Patterson ZR &Holahan MR. [https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fncel.2012.00058 Understanding the neuroinflammatory response following concussion to develop treatment strategies]. Review Article. Front. Cell. Neurosci.12 December 2012 </ref> There is no effective medicinal treatment for a concussion to date. | ||

== Exercise == | == Exercise == | ||

Prolonged rest beyond 24-48 hours after a concussion worsens rather than aids recovery. Humans respond well integrating in their social and physical environments, and therefore sustained rest adversely affects the physiology of concussion and can lead to physical deconditioning and reactive depression.<ref>Leddy JJ, Baker JG, Kozlowski K, et al. Reliability of a graded exercise test for assessing recovery from concussion. Clin J Sport Med 2011; 21:89</ref> | Prolonged rest beyond 24-48 hours after a [[Assessment and Management of Concussion|assessment and management of concussion]] worsens rather than aids recovery<ref name=":5">Lawrence DW, Richards D, Comper P, Hutchison MG. [https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0196062&type=printable Earlier time to aerobic exercise is associated with faster recovery following acute sport concussion.] PloS one. 2018 Apr 18;13(4):e0196062.</ref><ref>Lawrence DW, Richards D, Comper P, Hutchison MG. Earlier time to aerobic exercise is associated with faster recovery following acute sport concussion. ''PLoS One''. 2018;13(4):e0196062. </ref>. Humans respond well integrating in their social and physical environments, and therefore sustained rest adversely affects the physiology of concussion and can lead to physical deconditioning and reactive depression.<ref name=":6">Leddy JJ, Baker JG, Kozlowski K, et al. [http://concussion.ubmd.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/reliability.pdf Reliability of a graded exercise test for assessing recovery from concussion.] Clin J Sport Med 2011; 21:89</ref> It is strongly recommended that patients with concussion rest for 24-48 hours followed by a gradual and progressive return to non-contact, supervised, light aerobic activity (walking, stationary bicycle, or treadmill) at a subsymptom threshold (in other words avoid symptom exacerbation) until symptoms resolve, rather than strict physical rest<ref>Leddy JJ, Haider MN, Ellis M, Willer BS. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6089233/ Exercise is medicine for concussion.] Current sports medicine reports. 2018 Aug;17(8):262-70.</ref><ref name=":5" />. | ||

It is strongly recommended that patients with concussion rest for 24-48 hours followed by a gradual and progressive return to non-contact, supervised, light aerobic activity (walking, stationary bicycle, or treadmill) | |||

Twenty minutes a day of light cardiovascular exercise is recommended<ref name=":6" />. This can be broken down into 5 minute intervals or if tolerated in one full 20 minute session. If symptoms are worsened by light physical activity, then further activity should be deferred until it can be initiated without worsening of symptoms. In general, a rapid return to vigorous exertion is likely to exacerbate symptoms and, for most children, should be avoided.<ref name=":1">McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Dvorak J, et al. [https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/bjsports/early/2017/04/28/bjsports-2017-097699.full.pdf Consensus statement on concussion in sport-the 5(th) international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin,] October 2016. Br J Sports Med 2017.</ref><ref>Davis GA, Anderson V, Babl FE, et al. [https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/16ec/e89be460264b9ff5bba9d4a23715062d337f.pdf What is the difference in concussion management in children as compared with adults? A systematic review.] Br J Sports Med 2017; 51:949.</ref> A minimum of five days should pass before consideration of full return to competition.<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":3">Halstead ME, McAvoy K, Devore CD, et al. [https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/132/5/948.full.pdf Returning to learning following a concussion.] Pediatrics 2013; 132:948.</ref> | |||

== Sleep == | == Sleep == | ||

It is imperative that the patient normalises their sleep patterns<ref>Morse AM, Kothare SV. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780444639547000136 Sleep disorders and concussion]. InHandbook of clinical neurology 2018 Jan 1 (Vol. 158, pp. 127-134). Elsevier.</ref> for maximal glymphatic clearance following concussion. Your role as a physiotherapist is to integrate a behavioural regulation plan. This means instil good sleep hygiene, adequate nutrition and hydration, daily movement (non-contact) and management of stress<ref>Womble MN, Collins MW . [https://europepmc.org/abstract/med/27737280 Concussions in American football.] American journal of orthopaedics. Belle Mead NJ 2016;45(6):352–356.</ref> from the get-go. Good sleep hygiene recommendations include: | |||

* No caffeine consumption. On a molecular level, caffeine's alerting and sleep-disruptive effects are driven by blockade of adenosine receptors in the basal forebrain and hypothalamus.<ref>Roehrs T, Roth T. Caffeine: sleep and daytime sleepiness. Sleep Med Rev. 2008; 12:153–62.</ref> | * No caffeine consumption. On a molecular level, caffeine's alerting and sleep-disruptive effects are driven by blockade of adenosine receptors in the basal forebrain and hypothalamus.<ref>Roehrs T, Roth T. Caffeine: sleep and daytime sleepiness. Sleep Med Rev. 2008; 12:153–62.</ref> | ||

* No smoking: Nicotine promotes arousal and wakefulness, primarily through stimulation of cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain.<ref>Boutrel B, Koob GF. What keeps us awake: the neuropharmacology of stimulants and wakefulness-promoting medications. Sleep. 2004; 27:1181–94. </ref> | * No smoking: Nicotine promotes arousal and wakefulness, primarily through stimulation of cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain.<ref>Boutrel B, Koob GF. [https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article-pdf/27/6/1181/13662504/sleep-27-6-1181.pdf What keeps us awake: the neuropharmacology of stimulants and wakefulness-promoting medications]. Sleep. 2004; 27:1181–94. </ref> | ||

* Avoid alcohol: The brain is more vulnerable to the effects of alcohol after a concussion. Consumption of alcohol (even light amounts) shortly before bedtime can impair sleep that night. Since alcohol itself is a depressant, drinking alcohol after a concussion can increase the risk of developing depression. It also lengthens recovery time and interferes with cognition and balance. | * Avoid alcohol: The brain is more vulnerable to the effects of alcohol after a concussion. Consumption of alcohol (even light amounts) shortly before bedtime can impair sleep that night. Since alcohol itself is a depressant, drinking alcohol after a concussion can increase the risk of developing depression. It also lengthens recovery time and interferes with cognition and balance. | ||

* Regular exercise is a common sleep hygiene recommendation, with the caveat that exercise should be avoided close to bedtime.<ref name=":2">Stepanski EJ, Wyatt JK. Use of sleep hygiene in the treatment of insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2003; 7:215–25.</ref> Exercise may improve sleep through its effects on body temperature, arousal, and/or adenosine levels.<ref>Youngstedt SD. Effects of exercise on sleep. Clin Sports Med. 2005; 24:355–65.</ref> Please read exercise prescription above. | * Regular exercise is a common sleep hygiene recommendation, with the caveat that exercise should be avoided close to bedtime.<ref name=":2">Stepanski EJ, Wyatt JK. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1087079201902461 Use of sleep hygiene in the treatment of insomnia]. Sleep Med Rev. 2003; 7:215–25.</ref> Exercise may improve sleep through its effects on body temperature, arousal, and/or adenosine levels.<ref>Youngstedt SD. [https://www.sportsmed.theclinics.com/article/S0278-5919(04)00139-5/abstract Effects of exercise on sleep]. Clin Sports Med. 2005; 24:355–65.</ref> Please read exercise prescription above. | ||

* Encourage stress management techniques such as mindfulness/breathing exercises as a way to reduce arousal and worry prior to bedtime.<ref name=":2" /> Hall and colleagues<ref>Hall M, Vasko R, Buysse D, Ombao H, Chen Q, Cashmere JD, et al. Acute stress affects heart rate variability during sleep. Psychosom Med. 2004; 66:56–62.</ref> found that exposure to acute anticipatory stress close to bedtime resulted in increased sympathetic arousal, wakefulness throughout the night and less restorative sleep as measured by PSG. | * Encourage stress management techniques such as mindfulness/breathing exercises as a way to reduce arousal and worry prior to bedtime.<ref name=":2" /> Hall and colleagues<ref>Hall M, Vasko R, Buysse D, Ombao H, Chen Q, Cashmere JD, et al. [https://journals.lww.com/psychosomaticmedicine/fulltext/2004/01000/Acute_Stress_Affects_Heart_Rate_Variability_During.9.aspx Acute stress affects heart rate variability during sleep]. Psychosom Med. 2004; 66:56–62.</ref> found that exposure to acute anticipatory stress close to bedtime resulted in increased sympathetic arousal, wakefulness throughout the night and less restorative sleep as measured by polysomnography (PSG). | ||

* Keep the bedroom dark, quiet and cool. Sleep hygiene recommendations frequently advise individuals to minimize noise in their sleeping environment. Nocturnal noises within one's normal surroundings (local traffic, music, plumbing) have the potential to impact sleep, even if they are not consciously observed. | * Keep the bedroom dark, quiet and cool. Sleep hygiene recommendations frequently advise individuals to minimize noise in their sleeping environment. Nocturnal noises within one's normal surroundings (local traffic, music, plumbing) have the potential to impact sleep, even if they are not consciously observed. | ||

* Keep a consistent sleep schedule of regular bed and wake-up times. This is intended to maximize the synchrony between physiological sleep drive | * Keep a consistent sleep schedule of regular bed and wake-up times. This is intended to maximize the synchrony between physiological sleep drive and circadian rhythms. Homeostatic sleep drive and the circadian system work together to promote stable patterns of sleep and wakefulness.<ref>Dijk DJ, Czeisler CA. [http://www.jneurosci.org/content/jneuro/15/5/3526.full.pdf Contribution of the circadian pacemaker and the sleep homeostat to sleep propensity, sleep structure, electroencephalographic slow waves, and sleep spindle activity in humans.] J Neurosci. 1995; 15:3526–38.</ref> For children/adolescents specifically, don’t go to bed more than one hour later on weekends than your usual bedtime on school nights. School-aged children (6-12 years) need between 10 and 11 hours of sleep per night. Adolescents (13-18 years) require between 9 and 9.5 hours of sleep per night. | ||

* Napping for less than 30 minutes is beneficial to cognitive performance, alertness and mood.<ref>Dhand R, Sohal H. Good sleep, bad sleep! The role of daytime naps in healthy adults. CurrOpinPulm Med. 2006; 12:379–82.</ref><ref>Takahashi M. The role of prescribed napping in sleep medicine. Sleep Med Rev. 2003; 7:227–35. </ref> Please do not nap after 3pm in the afternoon. | * Napping for less than 30 minutes is beneficial to cognitive performance, alertness and mood.<ref>Dhand R, Sohal H. [https://journals.lww.com/co-pulmonarymedicine/Fulltext/2006/11000/Inhalational_anthrax_and_bioterrorism.2.aspx Good sleep, bad sleep! The role of daytime naps in healthy adults]. CurrOpinPulm Med. 2006; 12:379–82.</ref><ref>Takahashi M. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1087079202902418 The role of prescribed napping in sleep medicine.] Sleep Med Rev. 2003; 7:227–35. </ref> Please do not nap after 3pm in the afternoon. | ||

* Keep all electronics out of the bedroom. Your bedroom should be for sleeping only. Studies find that electronics, including televisions, cell phones, computers and video games, all interfere with sleep. | * Keep all electronics out of the bedroom. Your bedroom should be for sleeping only. Studies find that electronics, including televisions, cell phones, computers and video games, all interfere with sleep. | ||

* Pharmacotherapy may be necessary if sleep disturbance is prolonging recovery and sleep hygiene has not resulted in improvement. Consider a trial of melatonin; up to 3 mg in older children and 5 mg in adolescents.<ref>Zafonte RD, Mann NR, Fichtenberg NL. Sleep disturbance in traumatic brain injury: pharmacologic options. NeuroRehabilitation. 1996;7(3):189</ref> | * Pharmacotherapy may be necessary if sleep disturbance is prolonging recovery and sleep hygiene has not resulted in improvement. Consider a trial of melatonin; up to 3 mg in older children and 5 mg in adolescents.<ref>Zafonte RD, Mann NR, Fichtenberg NL. [https://content.iospress.com/articles/neurorehabilitation/nre7-3-04 Sleep disturbance in traumatic brain injury: pharmacologic options.] NeuroRehabilitation. 1996;7(3):189</ref> The lack of side effects or significant toxicity makes melatonin an attractive choice although efficacy in the setting of concussion is not established. Prolonged use of sedatives should be avoided. | ||

* Benzodiazepines should be avoided in patients with concussion because of day time sleepiness and memory impairment which hampers the assessment of recovery.<ref>Meehan WP (2011). Medical therapies for concussion. 3rd Clin Sports Med. 2011;30(1):115.</ref> | * Benzodiazepines should be avoided in patients with concussion because of day time sleepiness and memory impairment which hampers the assessment of recovery.<ref>Meehan WP (2011). [https://www.sportsmed.theclinics.com/article/S0278-5919%2810%2900055-4/fulltext Medical therapies for concussion.] 3rd Clin Sports Med. 2011;30(1):115.</ref> | ||

== Adolescent | == Adolescent Population == | ||

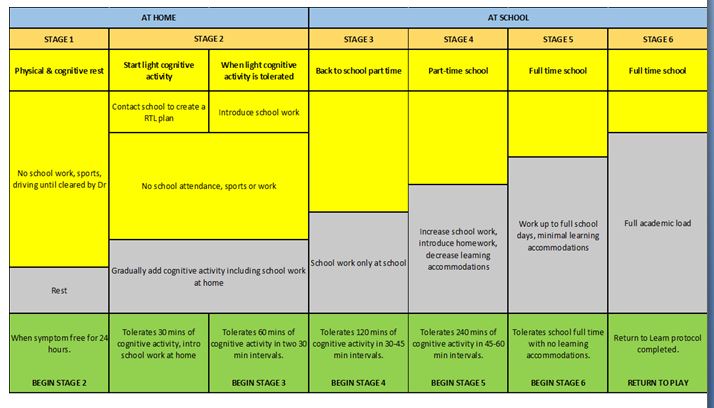

The adolescent and paediatric population are most at risk of post concussion syndrome, so a return to learn and return to play protocol has been stipulated, | The adolescent and paediatric population are most at risk of post concussion syndrome (PCS), so a return to learn (RTL) and return to play (RTP) protocol has been stipulated, Progress is intentionally slower in this specific population group, however this protocol can be adapted or modified to be specific to any patient population as a guideline for return to school/work and sport. In the adult population, the stages can be completed more quickly as long as the patient is not symptomatic. | ||

=== | === Return To Learn === | ||

[https://www.uptodate.com/contents/concussion-in-children-and-adolescents-management Concussion in | Latest research dictates that patients should only have 24-48 hours of cognitive and physical rest<ref name=":7">Meehan III WP, O’Brien MJ, Bachur RG. [https://www.uptodate.com/contents/concussion-in-children-and-adolescents-management Concussion in children and adolescents: Management]. [Accessed 30 September 2019]</ref>. Once patients can concentrate on a task and tolerate visual and auditory stimulation for 30 to 45 minutes (or approximately the length of the average school period), they may return to school with academic adjustments, as needed, until full recovery. The return to learn programme must be individualized and requires monitoring by the parent or legal guardian, school faculty, and managing physician. | ||

The following adjustments can be made to facilitate return to school or work:<ref name=":3" /><ref>McGrath N. [https://www.sportsmed.theclinics.com/article/S0278-5919%2810%2900055-4/fulltext Supporting the student-athlete's return to the classroom after a sport-related concussion]. J Athl Train 2010; 45:492.</ref><ref>Master CL, Gioia GA, Leddy JJ, Grady MF. [https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/9fb9/2fe6ab18571190ea907daeb96736332acdd0.pdf Importance of 'return-to-learn' in pediatric and adolescent concussion]. Pediatr Ann 2012; 41:1.</ref> | |||

The following adjustments can be made to facilitate return to school or work:<ref name=":3" /><ref>McGrath N. Supporting the student-athlete's return to the classroom after a sport-related concussion. J Athl Train 2010; 45:492.</ref><ref>Master CL, Gioia GA, Leddy JJ, Grady MF. Importance of 'return-to-learn' in pediatric and adolescent concussion. Pediatr Ann 2012; 41:1.</ref> | |||

* Limited course load | * Limited course load | ||

* Shortened classes or school/work day | * Shortened classes or school/work day | ||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

* Aids for learning (class notes, supplemental tutoring, desktop screen to limit blue light) | * Aids for learning (class notes, supplemental tutoring, desktop screen to limit blue light) | ||

* Postponement of deadlines, exams, weekly tests | * Postponement of deadlines, exams, weekly tests | ||

[[File:Concussion Management Toolkit for Physiotherapists.JPG]] | |||

''Figure 2: Return to learn (parachute Canada)'' | |||

{{#ev:youtube|g_eI34t4QiE}} | |||

== Return To Play (RTP) == | |||

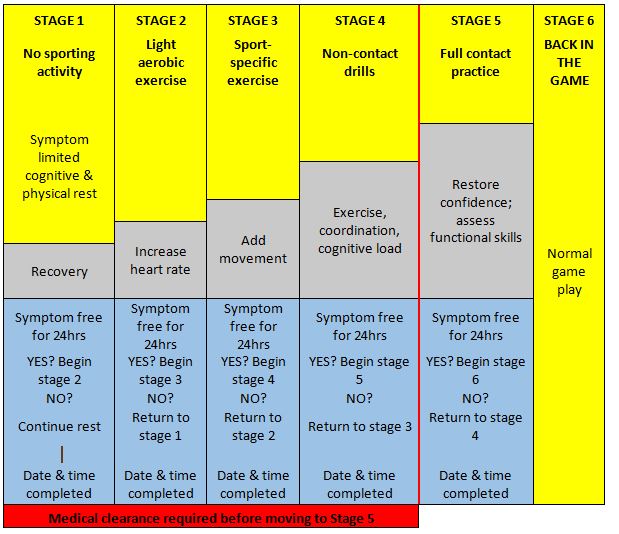

Prior to returning to full athletic participation, recovered athletes should complete a course of non-contact exercise challenges of gradually increasing intensity.<ref name=":1" /><ref>Halstead ME, Walter KD, Moffatt K, [https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/early/2010/08/30/peds.2010-2005.full.pdf Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical report--sport-related concussion in children and adolescents]. Pediatrics 2018; 142:e20183074.</ref><ref>Harmon KG, Drezner J, Gammons M, et al. [http://wspahn.camel.ntupes.edu.tw/ezcatfiles/t063/download/attdown/0/ACSM%20Position%20Stand%20Concussion%20CJSM%202013%20Harmon.pdf American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement: concussion in sport.] Clin J Sport Med 2013; 23:1.</ref> The graded RTP protocol advances through the following rehabilitation stages: light aerobic exercise, more intensive training, sports-specific exercises, non-contact participation, full practice, and ultimately, game play as shown below. | |||

The following are requirements for children and adolescents to begin the RTP protocol: | |||

* Successful return to school/work | |||

* Symptom-free and off any medications prescribed to treat the concussion. | |||

* Normal neurologic examination. | |||

* Back at baseline balance and cognitive performance measures. If baseline assessments are unavailable, age-adjusted normative data are available and can be useful in attempting to estimate premorbid levels of functioning for a given athlete. | |||

[[File:Concussion Management a Toolkit for Physiotherapists.JPG]] | [[File:Concussion Management a Toolkit for Physiotherapists.JPG]] | ||

''Figure 3: Return to play (Parachute canada)'' | |||

{{#ev:youtube|_55YmblG9YM}} | |||

== Useful Links == | |||

[https://cattonline.com/ Return to Learn protocol by GF Strong School Program (Vancouver School Board)], Adolescent and Young Adult Program, G.F. Strong Rehabilitation Centre. | |||

The Canadian website called [http://www.parachutecanada.org/injury-topics/item/concussion Parachute Canada]: Concussion gives a wealth of information and is a great resource for patients and health care practitioners.(accessed 27/8/2019). | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Interventions]] | |||

[[Category:Head]] | |||

[[Category:Head - Interventions]] | |||

[[Category:Course Pages]] | |||

[[Category:Plus Content]] | |||

Latest revision as of 08:39, 12 July 2023

Original Editor - Megyn Robertson

Top Contributors - Simisola Ajeyalemi, Kim Jackson, Mandy Roscher, Megyn Robertson, Robin Tacchetti, Samuel Adedigba, Rachael Lowe, Jess Bell, Olajumoke Ogunleye and Nupur Smit Shah

Concussion[edit | edit source]

Concussions can cause a host of variety of structural and physical impairments. Interventions for concussions need to be geared towards the patient's dysfunction as symptom presentations will differ among patients. [1][2]

Physical therapists interventions that may be included in concussive patients include, communication/education and addressing movement-related impairments, vestibular-oculomotor impairment and aerobic exercise as tolerated.[3]

Using Vestibular/Ocular-Motor Screening (VOMS) as Treatment[edit | edit source]

Research shows that 60% of concussive patients have vestibular/ocular-motor symptoms.[4] Exercise approaches to alleviate symptoms of vestibular hypofunction can be divided into two categories – namely adaptation or habituation exercises. Both exercise interventions lead to a reduction in the self-report measure of the impact of symptoms on the ability to function, a decrease in the sensitivity to movements, and an improvement in the ability to see clearly during head movements.

Habituation[edit | edit source]

Habituation exercises are given to patients who have certain types of inner ear disorders such as dizziness when they move their heads in certain ways. Habituation exercises are based on the idea that repeated exposure to a provocative stimulus (e.g. head movements) will lead to a reduction of the motion-provoked symptoms.[5][6] This change is thought to be due to long-term changes within the nervous system, and there is clinical evidence indicating that the habituation exercises can lead to long-term changes in symptoms.[7] The actual neural mechanism behind the effectiveness of the habituation exercises is not understood. Patients who perform habituation exercises will have a greater reduction in their motion sensitivity.

Adaptation[edit | edit source]

Adaptation exercises or gaze stability exercises are used to modify the magnitude of the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) in response to a given input (head movement)[8]. One of the signals that induces adaptation of the VOR is retinal slip combined with head movement.[9]. This is the basis for what has traditionally been considered adaptation exercises. These exercises require the individual to perform rapid, active head rotations while watching a visual target, with the stipulation that the target remains in focus during the head movements.[8][10] If the target is stationary, then the exercises are referred to as x1 viewing exercises. If the target is moving in the opposite direction of the head movement, then these exercises are referred to as x2 viewing exercises. While these exercises have been shown to improve dynamic visual acuity, the actual mechanism behind this improvement is not known.[11]Patients who perform gaze stability exercises will improve their dynamic visual acuity.

VOMS Treatment[edit | edit source]

In a nutshell, take what exacerbates patient symptoms and use that as your rehabilitation programme. Ease the patient into it, using graded exposure, until the patient is able to perform the activity without symptom exacerbation. Generally it is accepted to incorporate both habituation and adaptation in treatment regimes. Clendaniel[12] outlines an example of a home programme below with progressions. You can change the base of support and surfaces (stable to unstable) in conjunction with the VOMS progressions. You can also change the environment from quiet and low light to noisy and bright light as the patient tolerates for additional sensory load/input.

Exercise Progression[12]

| Gaze-Stabilization Exercises | Week | Habituation Exercises |

|---|---|---|

| Horizontal and vertical x1 viewing exercise with near target, 1 minute duration, sitting | 1 | Large amplitude, rapid cervical rotation (horizontal or vertical), each set of exercise consisted of 5 complete movements (cycles) and the individual performed 3 sets, sitting |

| Horizontal and vertical x1 viewing exercise with near target, 2 minute duration, sitting | 2 | Large amplitude, rapid horizontal cervical

rotation (seated) and standing pivots, or large amplitude, rapid vertical cervical rotation (seated) and seated trunk flexion-extension, 3 sets of 5 cycles |

| Horizontal and vertical x1 viewing exercise with near and far targets, 2 minute duration, standing | 3 | Large amplitude, rapid horizontal and vertical cervical rotation (seated) and standing pivots, or large amplitude, rapid horizontal and vertical cervical rotation (seated) and seated trunk flexion-extension,3 sets of 5 cycles |

| Horizontal and vertical x1 viewing exercise with near and far targets, and targets located in front of a busy background, 2 minute duration, standing | 4 | Large amplitude, rapid horizontal and vertical cervical rotation (seated), standing

pivots, and seated trunk flexion-extension, 3 sets of 5 cycles |

| Horizontal and vertical x1 viewing exercise with near and far targets, and targets located in front of a busy background. Horizontal and vertical x2 viewing exercise, plain background. All exercises 2 minute duration, standing | 5 | Large amplitude, rapid horizontal and vertical cervical rotation (standing), standing pivots, and seated trunk flexion-extension,3 sets of 5 cycles |

| Horizontal and vertical x1 viewing exercise with near and far targets, and targets located in front of a busy background. Horizontal and vertical x2 viewing exercise, busy background. All exercises 2 minute duration, standing | 6 | Large amplitude, rapid horizontal and vertical cervical rotation (standing), standing pivots (180 degrees), seated trunk flexion-extension, and Brandt- Daroff exercise 3 sets of 5 cycles |

Figure 1: Habituation and Adaptation progressions (Clendaniel,2010)

Medication[edit | edit source]

Data demonstrate that preventing an inflammatory response (through the use of non-steroidal anti inflammatories) to a concussion is not a viable treatment, despite its effectiveness in treating other traumatic injuries occurring in the CNS. The evidence suggests that the concussed brain presents a unique inflammatory signature as opposed to a general inflammatory response that occurs following any CNS injury.[13] There is no effective medicinal treatment for a concussion to date.

Exercise[edit | edit source]

Prolonged rest beyond 24-48 hours after a assessment and management of concussion worsens rather than aids recovery[14][15]. Humans respond well integrating in their social and physical environments, and therefore sustained rest adversely affects the physiology of concussion and can lead to physical deconditioning and reactive depression.[16] It is strongly recommended that patients with concussion rest for 24-48 hours followed by a gradual and progressive return to non-contact, supervised, light aerobic activity (walking, stationary bicycle, or treadmill) at a subsymptom threshold (in other words avoid symptom exacerbation) until symptoms resolve, rather than strict physical rest[17][14].

Twenty minutes a day of light cardiovascular exercise is recommended[16]. This can be broken down into 5 minute intervals or if tolerated in one full 20 minute session. If symptoms are worsened by light physical activity, then further activity should be deferred until it can be initiated without worsening of symptoms. In general, a rapid return to vigorous exertion is likely to exacerbate symptoms and, for most children, should be avoided.[18][19] A minimum of five days should pass before consideration of full return to competition.[18][20]

Sleep[edit | edit source]

It is imperative that the patient normalises their sleep patterns[21] for maximal glymphatic clearance following concussion. Your role as a physiotherapist is to integrate a behavioural regulation plan. This means instil good sleep hygiene, adequate nutrition and hydration, daily movement (non-contact) and management of stress[22] from the get-go. Good sleep hygiene recommendations include:

- No caffeine consumption. On a molecular level, caffeine's alerting and sleep-disruptive effects are driven by blockade of adenosine receptors in the basal forebrain and hypothalamus.[23]

- No smoking: Nicotine promotes arousal and wakefulness, primarily through stimulation of cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain.[24]

- Avoid alcohol: The brain is more vulnerable to the effects of alcohol after a concussion. Consumption of alcohol (even light amounts) shortly before bedtime can impair sleep that night. Since alcohol itself is a depressant, drinking alcohol after a concussion can increase the risk of developing depression. It also lengthens recovery time and interferes with cognition and balance.

- Regular exercise is a common sleep hygiene recommendation, with the caveat that exercise should be avoided close to bedtime.[25] Exercise may improve sleep through its effects on body temperature, arousal, and/or adenosine levels.[26] Please read exercise prescription above.

- Encourage stress management techniques such as mindfulness/breathing exercises as a way to reduce arousal and worry prior to bedtime.[25] Hall and colleagues[27] found that exposure to acute anticipatory stress close to bedtime resulted in increased sympathetic arousal, wakefulness throughout the night and less restorative sleep as measured by polysomnography (PSG).

- Keep the bedroom dark, quiet and cool. Sleep hygiene recommendations frequently advise individuals to minimize noise in their sleeping environment. Nocturnal noises within one's normal surroundings (local traffic, music, plumbing) have the potential to impact sleep, even if they are not consciously observed.

- Keep a consistent sleep schedule of regular bed and wake-up times. This is intended to maximize the synchrony between physiological sleep drive and circadian rhythms. Homeostatic sleep drive and the circadian system work together to promote stable patterns of sleep and wakefulness.[28] For children/adolescents specifically, don’t go to bed more than one hour later on weekends than your usual bedtime on school nights. School-aged children (6-12 years) need between 10 and 11 hours of sleep per night. Adolescents (13-18 years) require between 9 and 9.5 hours of sleep per night.

- Napping for less than 30 minutes is beneficial to cognitive performance, alertness and mood.[29][30] Please do not nap after 3pm in the afternoon.

- Keep all electronics out of the bedroom. Your bedroom should be for sleeping only. Studies find that electronics, including televisions, cell phones, computers and video games, all interfere with sleep.

- Pharmacotherapy may be necessary if sleep disturbance is prolonging recovery and sleep hygiene has not resulted in improvement. Consider a trial of melatonin; up to 3 mg in older children and 5 mg in adolescents.[31] The lack of side effects or significant toxicity makes melatonin an attractive choice although efficacy in the setting of concussion is not established. Prolonged use of sedatives should be avoided.

- Benzodiazepines should be avoided in patients with concussion because of day time sleepiness and memory impairment which hampers the assessment of recovery.[32]

Adolescent Population[edit | edit source]

The adolescent and paediatric population are most at risk of post concussion syndrome (PCS), so a return to learn (RTL) and return to play (RTP) protocol has been stipulated, Progress is intentionally slower in this specific population group, however this protocol can be adapted or modified to be specific to any patient population as a guideline for return to school/work and sport. In the adult population, the stages can be completed more quickly as long as the patient is not symptomatic.

Return To Learn[edit | edit source]

Latest research dictates that patients should only have 24-48 hours of cognitive and physical rest[33]. Once patients can concentrate on a task and tolerate visual and auditory stimulation for 30 to 45 minutes (or approximately the length of the average school period), they may return to school with academic adjustments, as needed, until full recovery. The return to learn programme must be individualized and requires monitoring by the parent or legal guardian, school faculty, and managing physician.

The following adjustments can be made to facilitate return to school or work:[20][34][35]

- Limited course load

- Shortened classes or school/work day

- Increased rest time

- Aids for learning (class notes, supplemental tutoring, desktop screen to limit blue light)

- Postponement of deadlines, exams, weekly tests

Figure 2: Return to learn (parachute Canada)

Return To Play (RTP)[edit | edit source]

Prior to returning to full athletic participation, recovered athletes should complete a course of non-contact exercise challenges of gradually increasing intensity.[18][36][37] The graded RTP protocol advances through the following rehabilitation stages: light aerobic exercise, more intensive training, sports-specific exercises, non-contact participation, full practice, and ultimately, game play as shown below.

The following are requirements for children and adolescents to begin the RTP protocol:

- Successful return to school/work

- Symptom-free and off any medications prescribed to treat the concussion.

- Normal neurologic examination.

- Back at baseline balance and cognitive performance measures. If baseline assessments are unavailable, age-adjusted normative data are available and can be useful in attempting to estimate premorbid levels of functioning for a given athlete.

Figure 3: Return to play (Parachute canada)

Useful Links[edit | edit source]

Return to Learn protocol by GF Strong School Program (Vancouver School Board), Adolescent and Young Adult Program, G.F. Strong Rehabilitation Centre.

The Canadian website called Parachute Canada: Concussion gives a wealth of information and is a great resource for patients and health care practitioners.(accessed 27/8/2019).

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Jabali MM, Alhakami AM, Qasheesh MA, Uddin S. Efficacy of physical therapy intervention in sports-related concussion among young individuals age-group–A narrative review. Saudi Journal of Sports Medicine. 2020 May 1;20(2):31.

- ↑ Lempke L, Jaffri A, Erdman N. The effects of early physical activity compared to early physical rest on concussion symptoms. Journal of sport rehabilitation. 2019 Jan 1;28(1):99-105.

- ↑ Quatman-Yates, Catherine C., Airelle Hunter-Giordano, Kathy K. Shimamura, Rob Landel, Bara A. Alsalaheen, Timothy A. Hanke, Karen L. McCulloch et al. "Physical therapy evaluation and treatment after concussion/mild traumatic brain injury: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health from the academy of orthopaedic physical therapy, American Academy of sports physical therapy, academy of neurologic physical therapy, and academy of pediatric physical therapy of the American Physical therapy association." Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 50, no. 4 (2020): CPG1-CPG73.

- ↑ Moser RS, Schatz P, Mayer B, Friedman S, Perkins M, Zebrowski C, Islam S, Lemke H, James M, Vidal P. Does time since injury and duration matter in the benefits of physical therapy treatment for concussion?. Journal of Concussion. 2021 Jun;5:20597002211020896.

- ↑ Shepard NT, Telian SA, Smith-Wheelock M, Raj A. Vestibular and balance rehabilitation therapy. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology 1993;102(3 Pt 1):198–205.

- ↑ Telian SA, Shepard NT, Smith-Wheelock M, Kemink JL. Habituation therapy for chronic vestibular dysfunction: preliminary results. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;103(1):89–95.

- ↑ Clement G, Tilikete C, Courjon JH. Retention of habituation of vestibulo-ocular reflex and sensation of rotation in humans. Exp Brain Res 2008 Sep;190(3):307–315.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Roller RA, Hall CD. A speed-based approach to vestibular rehabilitation for peripheral vestibular hypofunction: A retrospective chart review. Journal of Vestibular Research. 2018 Jan 1;28(3-4):349-57.

- ↑ Shelhamer M, Tiliket C, Roberts D, Kramer PD, Zee DS. Short-term vestibulo-ocular reflex adaptation in humans. II. Error signals. Exp Brain Res. 1994;100(2):328–336.

- ↑ Herdman SJ. Exercise strategies for vestibular disorders. Ear Nose Throat J 1989;68(12):961–964.

- ↑ Herdman SJ, Schubert MC, Das VE, Tusa RJ. Recovery of dynamic visual acuity in unilateral vestibular hypofunction. Arch.Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003;129(8):819–824.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Clendaniel RA . The effects of habituation and gaze-stability exercises in the treatment of unilateral vestibular hypofunction – preliminary results. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2010;34(2): 111–116.

- ↑ Patterson ZR &Holahan MR. Understanding the neuroinflammatory response following concussion to develop treatment strategies. Review Article. Front. Cell. Neurosci.12 December 2012

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Lawrence DW, Richards D, Comper P, Hutchison MG. Earlier time to aerobic exercise is associated with faster recovery following acute sport concussion. PloS one. 2018 Apr 18;13(4):e0196062.

- ↑ Lawrence DW, Richards D, Comper P, Hutchison MG. Earlier time to aerobic exercise is associated with faster recovery following acute sport concussion. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0196062.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Leddy JJ, Baker JG, Kozlowski K, et al. Reliability of a graded exercise test for assessing recovery from concussion. Clin J Sport Med 2011; 21:89

- ↑ Leddy JJ, Haider MN, Ellis M, Willer BS. Exercise is medicine for concussion. Current sports medicine reports. 2018 Aug;17(8):262-70.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Dvorak J, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport-the 5(th) international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br J Sports Med 2017.

- ↑ Davis GA, Anderson V, Babl FE, et al. What is the difference in concussion management in children as compared with adults? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2017; 51:949.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Halstead ME, McAvoy K, Devore CD, et al. Returning to learning following a concussion. Pediatrics 2013; 132:948.

- ↑ Morse AM, Kothare SV. Sleep disorders and concussion. InHandbook of clinical neurology 2018 Jan 1 (Vol. 158, pp. 127-134). Elsevier.

- ↑ Womble MN, Collins MW . Concussions in American football. American journal of orthopaedics. Belle Mead NJ 2016;45(6):352–356.

- ↑ Roehrs T, Roth T. Caffeine: sleep and daytime sleepiness. Sleep Med Rev. 2008; 12:153–62.

- ↑ Boutrel B, Koob GF. What keeps us awake: the neuropharmacology of stimulants and wakefulness-promoting medications. Sleep. 2004; 27:1181–94.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Stepanski EJ, Wyatt JK. Use of sleep hygiene in the treatment of insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2003; 7:215–25.

- ↑ Youngstedt SD. Effects of exercise on sleep. Clin Sports Med. 2005; 24:355–65.

- ↑ Hall M, Vasko R, Buysse D, Ombao H, Chen Q, Cashmere JD, et al. Acute stress affects heart rate variability during sleep. Psychosom Med. 2004; 66:56–62.

- ↑ Dijk DJ, Czeisler CA. Contribution of the circadian pacemaker and the sleep homeostat to sleep propensity, sleep structure, electroencephalographic slow waves, and sleep spindle activity in humans. J Neurosci. 1995; 15:3526–38.

- ↑ Dhand R, Sohal H. Good sleep, bad sleep! The role of daytime naps in healthy adults. CurrOpinPulm Med. 2006; 12:379–82.

- ↑ Takahashi M. The role of prescribed napping in sleep medicine. Sleep Med Rev. 2003; 7:227–35.

- ↑ Zafonte RD, Mann NR, Fichtenberg NL. Sleep disturbance in traumatic brain injury: pharmacologic options. NeuroRehabilitation. 1996;7(3):189

- ↑ Meehan WP (2011). Medical therapies for concussion. 3rd Clin Sports Med. 2011;30(1):115.

- ↑ Meehan III WP, O’Brien MJ, Bachur RG. Concussion in children and adolescents: Management. [Accessed 30 September 2019]

- ↑ McGrath N. Supporting the student-athlete's return to the classroom after a sport-related concussion. J Athl Train 2010; 45:492.

- ↑ Master CL, Gioia GA, Leddy JJ, Grady MF. Importance of 'return-to-learn' in pediatric and adolescent concussion. Pediatr Ann 2012; 41:1.

- ↑ Halstead ME, Walter KD, Moffatt K, Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical report--sport-related concussion in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2018; 142:e20183074.

- ↑ Harmon KG, Drezner J, Gammons M, et al. American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement: concussion in sport. Clin J Sport Med 2013; 23:1.