Calcaneal Fractures

Original Editor -

Top Contributors - Hajar Abdelhadji, Roxann Musimu , Dylan Van Calck

Definition / Description[edit | edit source]

A calcaneus fracture is a heel bone fracture. It is a rare type of fracture but has potentially debilitating results.Traditionally, a burst fracture of the calcaneus was known as "Lovers Fracture" as the injury would occur as a suitor would jump off a lover's balcony to avoid detection.[1]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

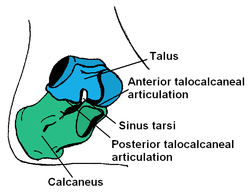

A good understanding of the anatomy of the calcaneus is essential in determining the patterns of injury and treatment goals and options. Calcaneus is the largest talar bone out of 7 tarsal bones which together with the talus for hind-foot. The calcaneus has a relatively thin cortex. It has 4 facets: 1 anteriorly which articulate with cuboid forming calcaneocuboid joint and 3 superiorly which articulate with talus forming talocalcaneal joint( subtalar joint). Subtalar joint allows inversion and eversion of the foot.

The sustentaculum tali is a medial bony projection supporting the neck of the talus. The sinus tarsi is a calcaneal groove comprising the anterior and middle facet and the talar sulcus. The lateral side of the calcaneus and its flat nature is highlighted as the most advantageous for internal fixation, but the poor soft tissue cover challenges wound healing. The medial side is associated closely with the posterior tibial neurovascular bundle and its branches making the surgical approach challenging. The sustentaculum tali is thought to be the most stable part of the calcaneus and relies on supporting tendons in maintaining its anatomical position in most fractures.

The calcaneus has four important functions:

- Acts as a foundation and support for the body’s weight

- Supports the lateral column of the foot and acts as the main articulation for inversion/eversion

- Acts as a lever arm for the gastrocnemius muscle complex

- Makes normal walking possible

These anatomic landmarks are important because fractures associated with these areas may cause involve joint involvement, tendon and neurovascular injury[2]

For more detailed anatomy see Ankle and Foot and Calcaneus

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

- Tarsal fractures account for 2% of all fractures.

- Calcaneal fractures account for 50-60% of all fractured tarsal bones.

- Less than 10% present as open fractures.

- They generally follow high-energy axial traumas, such as falls from height or motor accidents.

- 60% to 75% of calcaneum fractures are displaced and intra-articular. This can cause great disability due to pain and chronic stiffness, in addition to hindfoot deformities. These fractures are characterized clinically by poor functional results due to their complexity.

- Earlier, calcaneum fracture was predominately in male as they used to do more industrial work. But recent studies suggest regional variation in male and female predominance.

- Most patients with calcaneus fractures are young, with the 20-39 age group the most common.

- Comorbidities such as diabetes and osteoporosis may increase the risk of all types of fractures.

- Calcaneal fractures are rare in children.[1]

- Several authors have reported that the rehabilitation of these fractures can take from nine months to several years, which implicates a great economic burden on society.

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

- Calcaneal fractures are mostly the result of high energy events leading to axial loading of the bone.

- Predominantly, falls from height and automobile accidents (a foot depressed against an accelerator, brake, or floorboard) are common mechanisms of injury. The talus acting as a wedge causes depression and thus flatten, widen, and shorten the calcaneal body.

- Calcaneal fractures can also occur with less severe accidents like an ankle sprain or a stress fracture in runners.

- Jumping onto hard surfaces, blunt or penetrating trauma and twisting/shearing events may also cause calcaneus fracture.[1]

- Mostly, injuries occur in isolation. Most seen concomitant injuries were lower limb (13.2%) or spinal injuries (6.3%).[3]

- The posterior tibial neurovascular bundle run along the medial aspect of the calcaneal body and aisshielded by the sustentaculum tali thus neurovascular injuries are uncommon with calcaneal fractures.[1]

- Primary and secondary fracture lines develop. The primary fracture lines run through the posterior facet of the subtalar joint creating a superolateral fragment and a superomedial or “constant fragment” which includes the sustentaculum tali. If this force continues even further, a secondary fracture line is created and depending on the direction of the force, a tongue-type fracture or joint depression-type fracture will form.[4]

Characteristics / Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Initially, a patient may present with an above mentioned traumatic event with the following clinical features:

- Patients will present with diffuse pain, edema, and ecchymosis at the affected fracture site.

- The patient is not likely able to bear weight, walk and move foot.

- Swelling in the heel area

- Plantar ecchymosis extending through the plantar arch of the foot should raise suspicion significantly.

- There may be associated disability of the Achilles tendon, also raising the suspicion of a calcaneus injury.

- Skin quality around the heel must be evaluated for tenting and/or threatened skin. This is especially important in the setting of Tongue-type calcaneus fractures.[1]

- Generalized pain in the heel area that usually develops slowly (over several days to weeks): typically for stress fractures

- Deformity of the heel or plantar arch: Secondary to the displacement of the lateral calcaneal border outward, there is a possible widening or broadening of the heel.

Examination[edit | edit source]

- Palpation: Tenderness over calcaneus while squeezing the heel over the calcaneal.[5]

- A thorough neurovascular examination is must. For which pulse rate of ipsilateral dorsalis pedis or posterior tibial can be compared to contralateral limb.If there is any suspicion of arterial injury and prompt further investigation with angiography or Doppler scanning can be done.

- Evaluation of all lower extremity tendon function is also necessary.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Radiological examination:

X-ray: AP, lateral, and oblique plain films of the foot and ankle are needed. A harris view may be obtained which demonstrates the calcaneus in an axial orientation.

- Axial - Determines primary fracture line and displays the body, tuberosity, middle and posterior facets.

- Lateral - Determines Bohler angle.

- Oblique/Broden’s view - Displays the degree of displacement of the primary fracture line.

CT scan: It is gold standard for traumatic calcaneal injuries.

Bone scan or MRI: are recommended in stress fracture of the calcaneus.

Some of the reference angle and sign in the radiographic images are:

- Mondor's Sign is a hematoma identified on CT that extends along the sole and is considered pathognomic for calcaneal fracture.

- Bohler's Angle is defined as the angle between two lines drawn on plain film. The first line is between the highest point on the tuberosity and the highest point of posterior facet and the second is the highest point on the anterior process and the highest point on the posterior facet. The normal angle is between 20-40 degrees. It may be depressed on plain radiographs if it's calcaneus fracture.

- The Critical Angle of Gissane is defined as the angle between two lines drawn on plain film. The first along the anterior downward slope of the calcaneus and the second along the superior upward slope. A normal angle is 130-145 degrees. It may be increased in calcaneus fracture.

Classification[edit | edit source]

Calcaneal fractures can be classified into two general categories.

- Extraarticular fractures: It account for 25 % of calcaneal fractures. These typically are avulsion injuries of either the calcaneal tuberosity from the Achilles tendon, the anterior process from the bifurcate ligament, or the sustentaculum tali.

- Intraarticular Fractures: It account for the remaining 75%. The talus acts as a hammer or wedge compressing the calcaneus at the angle of Gissane causing the fracture.

Management/Intervention[edit | edit source]

Treatment of calcaneal fractures depends on the type of fracture and the extent of the injury. There is no universal treatment or surgical approach to all displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures. The choice of treatment must be based on the characteristics of the patient and on the type of fracture.

Operative Care[edit | edit source]

For the majority of patients, surgery is the correct form of treatment[6]. The goal of surgery is to restore the correct size and structure of the heel. Intra-articular fractures are often treated operatively. This is possible by performing an open reduction and internal fixation of the fracture. These procedures are performed through an incision on the outside of the heel. The calcaneus is put together and held in place with a metal plate and multiple screws. This procedure decreases the possibility of developing arthritis and maximizes the potential for inversion and eversion of the foot. Extra-articular fractures are generally treated conservatively.

Non-Operative Care[edit | edit source]

Nonoperative management is preferable when there is no impingement of the peroneal tendons and the fracture segments are not displaced (or are displaced less than 2 mm). Nonoperative care is also recommended when, despite the presence of a fracture, proper weight-bearing alignment has been adequately maintained and articulating surfaces are not disturbed. Extra-articular fractures are generally treated conservatively. Patients who are over the age of 50 years old or who have pre-existing health conditions, such as diabetes or peripheral vascular disease, are also commonly treated using nonoperative techniques. Patients receiving nonoperative management. [7][8]

R.I.C.E[edit | edit source]

- Rest: The affected foot must rest and the patient is not allowed to use the foot. This is to allow the fracture to heal.

- Ice: Several times a day the patient has an ice treatment to reduce inflammation, swelling and pain.

- Compression: Bandage / Compression stocking

- Elevation: The initial management is to reduce the swelling with rest in bed with the foot slightly above heart level.

Immobilisation[edit | edit source]

Partial or complete immobilisation is used if the fracture has not displaced the bone. Usually a cast is used to keep the fractured bone from moving. In the cast, the ankle is in neutral position and sometimes in slight eversion. To avoid weight bearing, crutches may be needed.

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

After the surgery, active range of motion exercises may be practiced with small amounts of movement for all joints of the foot and ankle. These exercises are used to maintain and regain the ankle joint movement. When needed for the involved lower extremity, the patient may continue with elevation, icing and compression. During the therapy, the patient will progress to gradual weight bearing. Patients may find this very difficult and painful. The physiotherapist conducts joint mobilisation to all hypomobile joints.

During the treatment, progressive resisted strengthening of the gastrocnemius muscles is done by weighted exercises, toe-walking, ascending and descending stairs and plyometric exercises. When the fracture is healed, the physiotherapist will progress the weight bearing in more stressful situations. This therapy consists of gait instruction and balance practice on different surfaces.

Outcome Measures

These are some outcome measures that can be used to measure the functional abilities of the patient to see the prognosis which can be used during the rehabilitation period.

Acute Stage[edit | edit source]

Immobilization. A cast, splint, or brace will hold the bones in your foot in proper position while they heal. You may have to wear a cast for 6 to 8 weeks — or possibly longer. During this time, you will not be able to put any weight on your foot until the bone is completely healed.[9]

Pre-Surgery[edit | edit source]

Initial stability is essential for open reduction internal fixation of intraarticular calcaneal fractures.

Preoperative revalidation consist on:

• Immediate elevation of the affected foot to reduce swelling

• Compression such as foot pump, intermittent compression devices or compression wraps.

• ICE

• Instructions for using wheelchair, bed transfers, or crutches.[8][10]

Post-Surgery[edit | edit source]

Both the progression of nonoperative and postoperative management of calcaneal fractures include traditional immobilization and early motion rehabilitation protocols. In fact, the traditional immobilization protocols of nonoperative and postoperative management are similar, and are thereby combined in the progression below. [11] Phases II and III of traditional and early motion rehabilitation protocols after nonoperative or postoperative care are comparable as well and are described together below. [3][12]

Phase I for Traditional Immobilization and Rehabilitation following Nonoperative and Postoperative Management: Weeks 1-4[edit | edit source]

Goals:

- Control oedema and pain

- Prevent extension of fracture or loss of surgical stabilization

- Minimize loss of function and cardiovascular endurance

Intervention:

- Cast with the ankle in neutral and sometimes slight eversion,

- Elevation

- Ice

- After 2-4 days, instruct in non-weight bearing ambulation utilizing crutches or walker

- Instruct in wheelchair use with an appropriate sitting schedule to limit time involved extremity spends in dependent-gravity position

- Instruct in comprehensive exercise and cardiovascular program utilizing upper extremities and uninvolved lower extremity

Phase II for Traditional Immobilization/Early Mobilization and Rehabilitation following Nonoperative and Postoperative Management: Weeks 5-8[edit | edit source]

Goals:

- Control remaining or residual oedema and pain

- Prevent re-injury or complication of fracture by progressing weight-bearing safely

- Prevent contracture and regain motion at ankle/foot joints

- Minimize loss of function and cardiovascular endurance

Intervention:

- Continued elevation, icing, and compression as needed for involved lower extremity

- After 6-8 weeks, instruct in partial-weight bearing ambulation utilizing crutches or walker

- Initiate vigorous exercise and range of motion to regain and maintain motion at all joints: tibiotalar, subtalar, midtarsal, and toe joints, including active range of motion in large amounts of movement and progressive isometric or resisted exercises

- Progress and monitor comprehensive upper extremity and cardiovascular program

Phase III for Traditional Immobilization/Early Mobilization and Rehabilitation following Nonoperative and Postoperative Management: Weeks 9-12[edit | edit source]

Goals:

- Progress weight-bearing status

- Normal gait on all surfaces

- Restore full range of motion

- Restore full strength

- Allow return to previous work status

Intervention:

- After 9-12 weeks, instruct in normal full-weight bearing ambulation with the appropriate assistive device as needed

- Progress and monitor the subtalar joint’s ability to adapt for ambulation on all surfaces, including graded and uneven surfaces

- Joint mobilization to all hypomobile joints including: tibiotalar, subtalar, midtarsal, and to toe joints

- Soft tissue mobilization to hypomobile tissues of the gastrocnemius complex, plantar fascia, or other appropriate tissues

- Progressive resisted strengthening of gastrocnemius complex through the use of pulleys, weighted exercise, toe-walking ambulation, ascending/descending stairs, skipping or other plyometric exercise, pool exercises, and other climbing activities

- Work hardening program or activities to allow return to work between 13- 52 weeks

Resources[edit | edit source]

http://ezinearticles.com/?Rehabilitation-After-Calcaneal-Fractures&id=4082480

http://orthopedics.about.com/od/footanklefractures/a/calcaneus.htm

http://xnet.kp.org/socal_rehabspecialists/ptr_library/09FootRegion/31Foot-CalcanealFracture.pdf

http://www.healthstatus.com/articles/Calcaneal_Fractures.html

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Calcaneal fractures can be divided into two groups: intra-articular en extra-articular calcaneal fractures. Intra-articular fractures have a lower prognosis. To determine the kind of fracture and if there is a fracture, medical imagery is needed. The rehabilitation programme consists of 3 stages postoperatively and are very important to enhance recovery.

Presentations[edit | edit source]

| fckLRImage:calcaneal_fracture_presentation.png|200px|border|left|fckLRrect 0 0 830 452 <a href="http://prezi.com/htzzh_lneqpu/calcaneal-fractures/">[n]</a>fckLRdesc nonefckLR | <a href="http://prezi.com/htzzh_lneqpu/calcaneal-fractures/">Calcaneal Fractures</a>

This presentation, created by Alice Thompson, provides an interactive insight into presentation, causes and types of calcaneal fractures as well as the evidence base for treatment options. <a href="http://prezi.com/htzzh_lneqpu/calcaneal-fractures/">Calcaneal Fractures/ View the presentation</a> |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Davis D, Newton EJ. Calcaneus Fractures.

- ↑ Daftary A, Haims AH, Baumgaertner MR. Fractures of the calcaneus: a review with emphasis on CT. Radiographics. 2005 Sep;25(5):1215-26.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Dhillon MS. Fractures of the calcaneus. JP Medical Ltd; 2013 Apr 30.

- ↑ Razik A, Harris M, Trompeter A. Calcaneal fractures: Where are we now?. Strategies in Trauma and Limb Reconstruction. 2018 Apr 1;13(1):1-1.

- ↑ Green, D. P. (2010). Rockwood and Green's fractures in adults (Vol. 1). C. A. Rockwood, R. W. Bucholz, J. D. Heckman, & P. Tornetta (Eds.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- ↑ Takasaka M, Bittar CK, Mennucci FS, de Mattos CA, Zabeu JL. Comparative study on three surgical techniques for intra-articular calcaneal fractures: open reduction with internal fixation using a plate, external fixation and minimally invasive surgery. Revista Brasileira de Ortopedia (English Edition). 2016 May 1;51(3):254-60.

- ↑ Buckly R. Operative compared with nonoperative treatment of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures. J. Bone Joint Surg., A. 2002;84:1733-44.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Griffin D, Parsons N, Shaw E, Kulikov Y, Hutchinson C, Thorogood M, Lamb SE. Operative versus non-operative treatment for closed, displaced, intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus: randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2014 Jul 24;349:g4483.

- ↑ Fischer, J.S.,MD; A. J. . Lowe, MD. (2016) Calcaneus (heel bone) fractures. Geraadpleegd op 5 december 2016.

- ↑ Lance EM, CAREY EJ, WADE PA. 9 Fractures of the Os Calcis: Treatment by Early Mobilization. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research (1976-2007). 1963 Jan 1;30:76-90.

- ↑ Joe Hodges PT, Robert Klingman,"Calcaneal Fracture and Rehabilitation".

- ↑ Hu QD, Jiao PY, Shao CS, Zhang WG, Zhang K, Li Q. Manipulative reduction and external fixation with cardboard for the treatment of distal radial fracture. Zhongguo gu shang= China journal of orthopaedics and traumatology. 2011 Nov;24(11):907-9.