Bronchiolitis

Original Editor - Jerome Ng

Top Contributors - Jerome Ng, Kim Jackson, Donald John Auson, Wendy Snyders, Naomi O'Reilly, WikiSysop, Adam Vallely Farrell, Vidya Acharya and Candace Goh

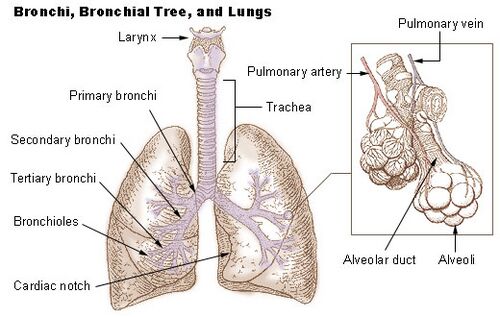

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The bronchioles do not have cartilage[1] where the bronchi have a firbrocartilaginous framework[2]. They are the final air conductors and do not have alveoli.[1]There are about 30000 terminal bronchioles, each of which directs air to about 10000 alveoli.[1] Bronchioles have a continuous circular layer of smooth muscle and the bronchi mucosa is continuous with the mucosa of the bronchioles.[2] The mucociliary blanket of the bronchioles is a watery fluid that accumulates muscous as it ascends the airway.[2]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

In the first year of life, bronchiolitis is the most common lower respiratory tract infection.[3][4]. It affects one in five infants and 2%-3% require admission to hospital.[3] It also has a seasonal predilection, with more infections during the winter.[5][6]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Bronchiolitis is usually caused by the Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV).[7][6] Other pathogens can also cause bronchiolitis such as human rhinovirus, influenza virus, coronavirus, human metapneumovirus (hMPV) and parainfluenza virus.[7]

Pathogenesis due to RSV[edit | edit source]

Inoculation of the conjunctival or nasal mucosa by contaminated secretions or inhalation of large respiratory droplets that contain the virus leads to infection. There is an incubation period of 4 - 6 days and then viral replication in the nasal epithelium leads to symptoms. Once the virus has spread to the lower respiratory tract, the alveolar pneumocytes and the ciliated epithelial cells of the mucosa of the bronchioles become infected. Impaired ciliary beating and the sloughing of the infected epithelium causes intraluminal obstruction. The bronchiolar epithelium starts to regenerate within 3 to 4 days after symptom resolution.[8]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

- Rhinorrhea (early presentation)[6][8]

- Nasal congestion[8]

- Cough[6][8]

- Tachypnoea[6][8]

- Increased work of breathing[6][8]

- Crackles and wheezing on auscultation[6][8]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis can be made through physical examination and history taking. Confirmatory laboratory studies can also be done to identify the causative agent as well as to rule out other pathologies.

Laboratory studies can include:

- Analaysis of specimen via:

- Indirect immunofluorescent-antibody assay (IFA)

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

- Reverse transcription-PCR

- Arterial blood gas analysis

- Blood culture

- Pulse oximetry

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Management / Interventions[edit | edit source]

- Hydration

- Respiratory support

- Nasal suctioning

- Supplemental oxygen

The following are interventions that may be used, but not as a routine intervention:

- Trial of inhaled bronchodilator

- Nebulized hypertonic saline

- Glucocorticoids

- Chest physiotherapy

Key Evidence[edit | edit source]

In the Cochrane review titled "Chest physiotherapy for acute bronchiolitis in children younger than two years of age", it was concluded that none of the chest physiotheray techniques (vibrations, percussions, slow passive expiratory techniques or forced expiratory techniques) have demonstrated a reduction in the severity of disease. Hence, these tecniques cannot be used as standard clinical practice for hospitalised patients with severe bronchiolitis.[10]

A state-of-art review suggests avoiding repeated airway clearance in infants and children with acute pulmonary disease.[11]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Leslie KO, Wick MR. Bronchiole [Internet]. Bronchiole - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. [cited 2023Jan14]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/immunology-and-microbiology/bronchiole

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Lust RM. Bronchiole [Internet]. Bronchiole - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. [cited 2023Jan14]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/immunology-and-microbiology/bronchiole

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ricci V, Nunes VD, Murphy MS, Cunningham S. Bronchiolitis in children: summary of NICE guidance. Bmj. 2015 Jun 2;350.

- ↑ O'Brien S, Borland ML, Cotterell E, Armstrong D, Babl F, Bauert P, Brabyn C, Garside L, Haskell L, Levitt D, McKay N. Australasian bronchiolitis guideline. Journal of paediatrics and child health. 2019 Jan;55(1):42-53.

- ↑ Bronchiolitis. nhs.uk. [cited 13 April 2020]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/bronchiolitis/

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 Florin TA, Plint AC, Zorc JJ. Viral bronchiolitis. The Lancet. 2017 Jan 14;389(10065):211-24.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Miller EK, Gebretsadik T, Carroll KN, et al. Viral etiologies of infant bronchiolitis, croup and upper respiratory illness during 4 consecutive years. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(9):950–955. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e31829b7e43 Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3880140/

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 Meissner HC. Viral bronchiolitis in children. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016 Jan 7;374(1):62-72.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 White DA, Zar HJ, Madhi SA, Jeena P, Morrow B, Masekela R, Risenga S, Green RJ. Acute viral bronchiolitis in South Africa: Diagnostic flow. SAMJ: South African Medical Journal. 2016 Apr;106(4):328-9.

- ↑ Roqué i Figuls M, Giné-Garriga M, Granados Rugeles C, Perrotta C, Vilaró J. Chest physiotherapy for acute bronchiolitis in paediatric patients between 0 and 24 months old. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD004873. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004873.pub5.

- ↑ Morrow BM. Airway clearance therapy in acute paediatric respiratory illness: A state-of-the-art review. South African Journal of Physiotherapy. 2019 Jun 25;75(1):12.