Boutonniere Deformity: Difference between revisions

(added ref to videos) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

Boyes test may become positive only in late stages. | Boyes test may become positive only in late stages. | ||

{{#ev:youtube|m71MIeqLzys}}<ref name=":11" /> | {{#ev:youtube|m71MIeqLzys}}<ref name=":11" /> | ||

<div class="row"> | |||

<div class="col-md-6"> {{#ev:youtube|QbU0mPWtsE|250}} </div> | |||

<div class="col-md-6"> {{#ev:youtube|m71MIeqLzys|250}} </div> | |||

</div> | |||

== Treatment == | == Treatment == | ||

Treatment options include prolonged splinting or surgery for patients who present for evaluation with a chronic injury. | Treatment options include prolonged splinting or surgery for patients who present for evaluation with a chronic injury. | ||

Revision as of 19:25, 4 October 2020

Original Editor - Esraa Mohamed Abdullzaher

Top Contributors - Shreya Pavaskar, Wanda van Niekerk, Adu Omotoyosi Johnson, Esraa Mohamed Abdullzaher, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka and Kim Jackson

Definition[edit | edit source]

It is a deformity of the fingers or toes in which the proximal interphalangeal joint (PIPJ) is flexed and the distal interphalangeal joint (DIPJ) is hyperextended. It is an extensor zone 3 injury. It is also called as Buttonhole deformity.[1]

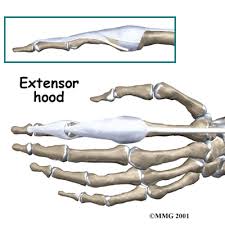

Clinically relevant anatomy[edit | edit source]

The Extensor Digitorum Communis (EDC) tendon at each finger splits into three bands namely the central tendon, which inserts on the base of the middle phalanx, and two lateral bands, which rejoin as the terminal tendon to insert into the base of the distal phalanx. In order to produce active interphalangeal extension, the EDC muscle requires the assistance of two intrinsic muscle groups that also have attachments to the extensor hood and the lateral bands. The EDC tendon and all its complicated active and passive interconnections at and distal to the metacarpophalangeal joint are known together as the extensor mechanism. The foundation of the extensor mechanism is formed by the tendons of the EDC muscle (with extensor indicis proprius and extensor digiti minimi and the extensor hood, the central tendon, and the lateral bands that merge into the terminal tendon. The triangular ligament helps stabilize the bands on the dorsum of the finger. The triangular ligament provides stability to the lateral bands preventing palmar subluxation during PIPJ flexion. [3]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Boutonniere Deformity (BD) may develop secondary to trauma (including a direct laceration to the extensor mechanism), secondary to rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and in the setting of burns. There are even reports of congenital BDs[4]The pathogenesis of a BD varies according to its etiology. [5]

Patients who suffer a traumatic BD may have been subject to a direct injury to the central slip or a force that placed the central slip on stretch, leading to failure of the extensor mechanism. Direct injuries can occur when lacerations disrupt the central slip. Central slip injuries may also occur in the setting of passively forced flexion of an actively extended PIP joint. In another scenario, a volar PIP joint dislocation can avulse the dorsal lip of the middle phalanx base and create a central slip disruption.

BDs in the setting of RA develop and progress over time as the soft tissues of the digit are compromised. Specifically, synovial proliferation within the PIP joint results in stretching of the extensor mechanism. Consequently, a subtle extensor lag may develop as the central slip is unable to achieve full extension.

With the PIP joint in slight flexion, the lateral bands are subluxated volarly and become fixed volar to the axis of rotation. Furthermore, the oblique retinacular ligaments contract, resulting in hyperextension and restricted flexion at the DIP joint. Early in the progression of the deformity, the joints remain passively correctable; however, over time, capsular tissues contract, and fibrosis occur within and around the PIP joint. At this time, the BD becomes a fixed deformity.[6]

BDs secondary to burns may occur due to direct injury of the central slip, as in the case of a full-thickness burn. Alternatively, the central slip may be injured by the onset of infection; in rare cases, the central slip may undergo ischemic necrosis resulting from the pressure of an overlying eschar.[7],[8]

Case reports have described congenital BDs. [9],[10] Such cases offer an interesting perspective into how altered anatomy may affect the forces across the metacarpophalangeal (MCP), PIP, and DIP joints. In one such report, Kim et al described BDs of bilateral little fingers secondary to an extensor mechanism that failed to trifurcate into a central slip and two lateral bands, and that consequently failed to insert at the dorsal base of the middle phalanx. [4]Presumably, as a result, the triangular ligament also failed to develop.

Mechanism/Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

Mechanism

If the central slip of the digital expansion is ruptured, minimal deformity results as long as the transverse fibers of the expansion remain intact. If they are also torn, a deformity is produced at the PIP joint. In this case, all extensor force will be transmitted to the distal phalanx by intact lateral bands, producing hyperextension of the DIP joint. The PIP joint buckles into flexion and protrudes through the breach in the extensor hood. The two lateral bands will now run on the palmar aspect of the PIP joint and will exaggerate flexion.[11]

The deformity is the result of a rupture of the central tendinous slip of the extensor hood and is most common after trauma or in rheumatoid arthritis.[12]

Pathophysiology

A boutonniere deformity (BD) occurs as a consequence of disruption of the central slip of the extensor tendon and attenuation of the triangular ligament, which connects the lateral bands to the terminal tendon. This disruption permits each of the conjoint lateral bands of the digit to slide volarly. Once the lateral bands slide volar to the axis of rotation of the PIP joint, this joint is subjected to a pathologic flexion force and an extension lag; all tendons traversing the PIP joint in this setting elicit flexion of the joint.

Signs and Symptoms[edit | edit source]

Signs of boutonnière deformity can develop immediately following an injury to the finger or may develop a week to 3 weeks later.

- The finger at the middle joint cannot be straightened and the fingertip cannot be bent.

- a weak grip and an inability to grasp and manipulate small objects with the tip of the digit.

- Swelling and pain occur and continue on the top of the middle joint of the finger.[14]

There are 2 special tests that help in identifying injury to the extensor mechanism :

- Elson Test - Fixing PIP Joint at 90° and ask to extend DIP; positive if unable to extend DIP[15].

- Boyes Test - Extend PIP and ask to flex DIP; positive is unable to flex DIP actively[16]

Boyes test may become positive only in late stages.

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Treatment options include prolonged splinting or surgery for patients who present for evaluation with a chronic injury.

| Stage | PIP Joint | DIP Joint |

|---|---|---|

| 1 - Mild,

Passively correctable, Normal articular surface. |

Splinting Injection and/or synovectomy | Extensor tenotomy |

| 2 - Moderate,

Passively correctable, Normal articular surface. |

Treat as stage 1 ± Extensor reconstruction | Extensor tenotomy |

| 2 - Moderate,

Partially passively correctable, Normal articular surface. |

Treat as stage 1 Convert to correctable Extensor reconstruction | Extensor tenotomy |

| 2 - Moderate to severely fixed,

Normal articular surface. |

Treat as above If correctable → Extensor reconstruction If not correctable →Salvage →Rarely volar release | Extensor tenotomy |

| 3 - Joint destruction | Arthrodesis or arthroplasty | Extensor tenotomy |

Physiotherapy management[edit | edit source]

Treatment for an acute injury is uninterrupted splinting of the PIP in full extension for 6 weeks. An extensor lag greater than 15° is an indication to splint the DIP joint in slight flexion for several weeks to allow healing.[17] After 6 weeks of immobilization, exercises are begun. The exercise involves two sequential maneuvers. The first is active assisted PIP joint extension. This will stretch the tight volar structures, will cause the lateral bands to ride dorsal to the PIP joint axis, and will put longitudinal tension on the lateral bands and oblique retinacular ligaments. The second maneuver is maximal active forced flexion of the DIP joint while the PIP joint is held at 0°or as close to that position as the PIP will allow. This will gradually stretch the lateral bands and oblique retinacular ligaments to their physiologic length. Continue splinting 2 to 4 weeks when not exercising. When full PIP joint extension can be maintained throughout the day, then night splinting only is appropriate. Length of treatment and splinting maybe several weeks.[11]

Surgical management[edit | edit source]

While nonsurgical treatment of boutonnière deformity is preferred, surgery is an option in certain cases, such as when:

- The deformity results from rheumatoid arthritis.

- The tendon is severed.

- A large bone fragment is displaced from its normal position.

- The condition does not improve with splinting.

Surgery can reduce pain and improve functioning, but it may not be able to fully correct the condition and make the finger look normal. If the boutonniere deformity remains untreated for more than 3 weeks, it becomes much more difficult to treat.[14]

Occupational Therapy[edit | edit source]

An Oval-8 Finger Splint which is basically a three point splint[18] holds PIP in a straight line and allows DIP to move freely. It is easily removable and washable. It is also available in a tube for more comfort and cushioning effect. Splinting is usually required for 6 weeks in conservative treatment.[19] DIP flexion exercises, with the PIP held in extension promotes pull through of the lateral Bands dorsally from the volar subluxed position.

Capener splint is a dynamic extension splint can also be introduced to improve strength and mobility[21].

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Coons MS, Green SM. Boutonniere deformity. Hand clinics. 1995 Aug;11(3):387-402.

- ↑ Terrono A, Millender L, Nalebuff E. Boutonniere rheumatoid thumb deformity. The Journal of hand surgery. 1990 Nov 1;15(6):999-1003.

- ↑ Levangie PK, Norkin CC. Joint Structure and function: a comprehensive analysis. 3rd. Philadelphia: FA. Davis Company. 2000.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kim JP, Go JH, Hwang CH, Shin WJ. Restoration of the central slip in congenital form of boutonniere deformity: case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2014 Oct. 39 (10):1978-81. [Medline]

- ↑ Feldon P, Terrono AL, Nalebuff EA, Millender LH. Rheumatoid arthritis and other connective tissue diseases. Wolfe SW, Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, Kozin SH, eds. Green’s Operative Hand Surgery. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2011. 2: 2052-6

- ↑ Muir IFK, Barclay TL. Burns and Their Treatment. London: Lloyd-Luke; 1962. 109

- ↑ Grishkevich VM. Surgical treatment of postburn boutonniere deformity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996 Jan. 97 (1):126-32. [Medline].

- ↑ Tsuge K. Congenital aplasia or hypoplasia of the finger extensors. Hand. 1975 Feb. 7 (1):15-21. [Medline]

- ↑ Carneiro RS. Congenital attenuation of the extensor tendon central slip. J Hand Surg Am. 1993 Nov. 18 (6):1004-7. [Medline].

- ↑ Elson RA. Rupture of the central slip of the extensor hood of the finger. A test for early diagnosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1986 Mar. 68 (2):229-31. [Medline].

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Darlene Hertling and Randolph M. Kessler,Management of common musculoskeletal disorders.4th ed,1983.

- ↑ David J Magee,Orthopedic Physical Assesment.1987.

- ↑ Terrono A, Millender L, Nalebuff E. Boutonniere rheumatoid thumb deformity. The Journal of hand surgery. 1990 Nov 1;15(6):999-1003.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases--conditions/boutonniere-deformity/

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Elson RA. Rupture of the central slip of the extensor hood of the finger. A test for early diagnosis. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 1986 Mar;68(2):229-31.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Boyes JH. Bunnell's Surgery of the Hand. 5th ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1971. 393.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Williams K, Terrono AL. Treatment of boutonniere finger deformity in rheumatoid arthritis. The Journal of hand surgery. 2011 Aug 1;36(8):1388-93.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Porter BJ, Brittain A. Splinting and hand exercise for three common hand deformities in rheumatoid arthritis: a clinical perspective. Current opinion in rheumatology. 2012 Mar 1;24(2):215-21.

- ↑ Moussallem CD, El-Labaky CY, El-Yahchouchi CA, Hoyek FA, Lahoud JC. Extensor Tendon Injuries. Journal of Hand Surgery. 2011 Feb 1;36(2):368.

- ↑ Barnes DE, inventor; Mayo Foundation for Medical Education, assignee. DIP joint extension splint. United States patent US 7,914,474. 2011 Mar 29.

- ↑ Yang G, McGlinn EP, Chung KC. Management of the stiff finger: evidence and outcomes. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2014 Jul 1;41(3):501-12.

- ↑ Taylor E, Hanna J, Belcher HJ. Splinting of the hand and wrist. Current Orthopaedics. 2003 Dec 1;17(6):465-74.

.