Benefits of Physical Activity of Children With Cerebral Palsy in Mainstream Schools

INTRODUCTION[edit | edit source]

The following wiki page is designed primarily for teachers and staff of mainstream schools. The aim of this resource is to highlight, educate and create awareness for the reader of the benefits and requirements of physical activity for children diagnosed with cerebral palsy in a mainstream school setting.

It is hoped that the principles highlighted will be of benefit to mainstream school teachers and the wider population, seeking to promote daily physical activity amongst children with cerebral palsy.

LEARNING OUTCOMES[edit | edit source]

- Recognize and describe the common clinical manifestations of CP and the potential impacts on participation in the school setting.

- Evaluate the importance and benefits of physical activity in students with CP.

- Construct a tailored teaching plan to accommodate specific needs of students with CP.

- Demonstrate improved awareness and application of current guidelines and recommendations for students with CP in the mainstream school setting.

WHAT IS CEREBRAL PALSY[edit | edit source]

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a well recognised neurodevelopmental condition beginning in early childhood and persisting throughout an individual’s life. Mutch et al (1992) defined CP as “an umbrella term covering a group of non- progressive, but often changing, motor impairment syndromes secondary to lesions or anomalies of the brain arising in the early stages of development”. In the western world, a total of 2-2.5 of every 1000 born children have CP. Cerebral Palsy is caused by a brain injury or brain malformation occurring during either the foetal development, at birth or after birth during which time the brain is still developing.

The primary conditions affected by Cerebral Palsy are motor impairments, such as:

• muscle stiffness or floppiness

• muscle weakness

• random and uncontrolled body movements

• balance and co-ordination problems

What are the different types of Cerebral Palsy?[edit | edit source]

Cerebral Palsy can be characterised in a number of different ways.

Physiological grouping

• Spasticity – This causes the muscles to become stiff, making movement difficult and the muscles are referred to as having “high Tone”. Spasticity is present in around 80% of cerebral palsy cases.

• Athetoid or Dyskinesia – This causes unwanted abnormal movements and involuntary muscle spasms which can be difficult to control and are sometimes painful. These are a result of incorrect signals from the brain which cause fluctuations in muscle tone that affects the entire body. It occurs in 10-20% of cerebral palsy cases.

• Ataxia – this causes the muscle to have low tone and is often described as being floppy. There is generally a disturbance of the coordination of voluntary movements due to muscle dysnyergia which leads to an unsteady gait and difficulty with fine motor tasks.. It affects 5-10% of cerebral palsy cases.

• Mixed group - Individuals in this group generally have a combination of the above mentioned dysfunctions.

Anatomic Grouping

Another way used clinically to categorise children with CP is by the parts of the body affected in. It is known as topography of Cerebral Palsy:

• Hemiparesis (hemiplegia) - predominantly unilateral impairment of arm and leg on the same side.

• Diplegia - motor impairment primarily of the legs (usually with some relatively limited involvement of arms).

• Triplegia – three limbs involved

• Quadriplegia (tetraplegia) – all four limbs are functionally compromised.

Motor Function

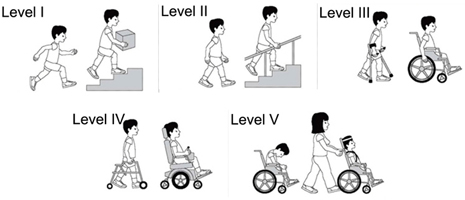

Functional status can be categorised by using the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS). This classification system groups children with cerebral palsy into one of five levels dependent on functional mobility or activity limitation and the distinctions between levels must be meaningful in everyday life. The GMFCS for cerebral palsy is based on self-initiated movement, with emphasis on sitting, transfers, and mobility. Distinctions are based on functional limitations, the need for hand-held mobility devices or wheeled mobility and to a lesser extent, quality of movement. In 2007 a revised and expanded GMFCS was released. This broke down the categories for different age groups, namely; before 2nd birthday, between 2nd and 6th birthday, between 4th and 6th birthday, between 6th and 12th birthday and between 12th and 18th birthday. The breakdown for each age group can be seen here LINK.

The general headings used for each level are seen here:

• LEVEL I – Walks without limitations

• LEVEL II – Walks with limitations

• LEVEL III – Walks using a hand held mobility device.

• LEVEL IV – Self mobility with limitations, May use powered mobility

• LEVEL V – Transported in a manual wheelchair.

Associated Problems[edit | edit source]

Children with cerebral palsy can also have a range of associated conditions or problems, including:

• learning difficulties: although intelligence is often unaffected

• hearing loss

• visual impairment: 20%

• sensory impairment of hand: about 1/2

• speaking difficulties (dysarthria): up to 80%

• chronic pain: more than 1/4

• skeletal abnormalities, particularly hip dislocation or an abnormally curved spine (scoliosis)

• repeated seizures or fits (epilepsy): 20-40%

• drooling and swallowing difficulties (dysphagia)

• gasto-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD): 1/2

• difficulty controlling their bladder (urinary incontinence)

• constipation

(NHS Choice; Beckung & Hagberg, 2002; Schenker, 2005)

Signs and symptoms of cerebral palsy may not always be apparent at birth. In the first 12-18 months of life, Cerebral palsy except in its mildest forms can be seen and diagnosed in children.

Cerebral Palsy – Some Frequently asked Questions[edit | edit source]

• Q. Is CP a life threatening condition?

With the exception of children born with very severe cases, CP is considered to be a non life threatening condition. The vast majority of children with CP are expected to live well into adult life.

• Q. Is CP a curable condition?

Unfortunately CP is not a curable condition. CP is damage to the brain that cannot be reversed. However treatment and therapy can help manage its effects on the body.

•Q. Is CP a Progressive Condition?

No CP is not a progressive condition due to it being as a result of a one time brain injury and no further degeneration of the brain will occur.

• Q. Is Cerebral Palsy a permanent condition?

Yes CP is permanent as the injury to the brain is permanent. The brain does not have the have the same healing properties as other parts of the body. Due to this, CP itself will not change for better or worse throughout the individuals lifetime, however associative conditions may change over time.

• Q. Is Cerebral Palsy manageable?

Yes!! Treatment, therapy, surgery and technology can help maximise the indepence of individuals with CP. These can help reduce barriers, increase inclusion and lead to a better and enhanced quality of life.

•Q. Is Cerebral Palsy a chronic condition?

Yes, the effects of CP are long term, not temporary. An individual diagnosed with CP will have the condition for the entirety of their life.

<

Current state of physical activity inclusion of students with CP in mainstream primary schools[edit | edit source]

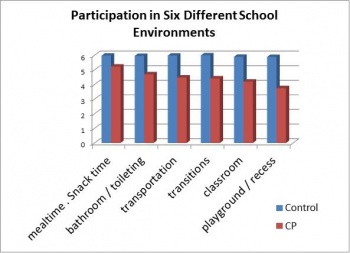

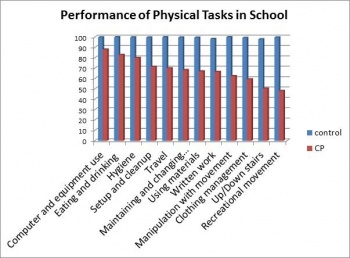

Schenker’s study (2005) found that there were significant differences between participation and activity performance of body-abled students and students with CP included in mainstream primary schools. Furthermore, activity performance limitations had negative impact on school participation (Figure 1-3). Children with CP were actively involved in a wide range of leisure activities and experienced a high level of enjoyment. However, involvement was lower in skill-based and active physical activities as well as community-based activities (Majnemer, 2008).

Figure 1. Children with CP had reduced participation in 6 different school environments compared to body-abled children; the level of participation depends on the physical demand of environment. For example, children with CP had lowest participation in activities in playground and recess which demand highest active physical abilities (modified from Schenker, 2005).

Figure 2. Children with CP had lower level of performance in both physical tasks compared to body-abled students (modified from Schenker, 2005).

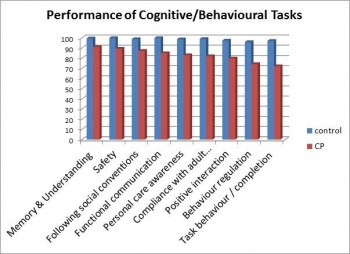

Figure 3. Children with CP also had lower level of performance in cognitive/behavioural tasks compared to body-abled students (modified from Schenker, 2005).

Challenging behaviour

Children with CP in mainstream school appear to have some form of challenging behaviour which may reflect some need being unfulfilled, or a problem with communication. Figure 2 showed that behavior regulation of students with CP was much lower than that of body-abled students. Challenging behaviour reflects the fact that there is something going wrong that needs to be addressed. It can be a challenge to professionals, teachers, carers and parents. It shows that there is some need being unfulfilled, or a problem with communication, not that there is a person doing something wrong who needs to be stopped. A child with CP is more likely to have challenging behaviour, which is contributed by a combination of impairments, environment, interpersonal relationships and other factors. Children with CP have to develop some form of behaviour in order to have their needs met (Scope).

Learning Difficulties

A large proportion of children with cerebral palsy have learning difficulties, though they have a similar range of intelligence as body-abled children (Beckung & Hagberg, 2002; Schenker, 2005). The prevalence of learning difficulties increases when epilepsy is present. Learning difficulties include the difficulties understanding new or complex information, learning new skills, and coping independently. Children with learning difficulties can suffer from the same mental health and emotional difficulties that others do. In many cases they can be less well equipped and supported to deal with them (Scope).

EDUCATION FOR CHILDREN WITH A DISABILITY[edit | edit source]

It is the right of every child between the ages of 5 – 16 years old to receive an education, and to be offered a free place at a state school (Education and Learning, 2014). This framework extends to children and young adults with disability. The Equality Act (2010) states that it is against the law for schools and other education providers to discriminate against children with disability.

Special education needs (SEN) is an umbrella term utilized to describe individuals who have learning difficulties or disabilities which make it harder for them to learn than most other individuals of the same age. The four areas highlighted to be challenging are:

-Communicating and interacting

- Cognition and learning

- Social, emotional and mental health difficulties

- Sensory and/ or physical needs

(0-25 SEND Code of Practice(2014)

Disability exists in many children and young people who have SEN. The Equality Act (2010) defines disability as; ‘A physical or mental impairment which has a long-term (a year or more) and substantial adverse effect on their ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities.’ Cerebral Palsy is classed as a disability as it is a life-long condition which needs regular input for specialists and therapists.

Individuals with disability often require higher levels of provision, to ensure they are given the same opportunities than those who are not disabled (Debenham, 2012). In order to aid the delivery of the national curriculum to children and young people with SEN, an Individual Education Plan (IEP) can be designed to optimise the education that individual receives. Using the curriculum being followed as a basis, the IEP creates strategies which are being utilised in order to help them meet their additional needs.

MOVEMENT OPPORTUNITIES VIA EDUCATION (MOVE) PROGRAMME[edit | edit source]

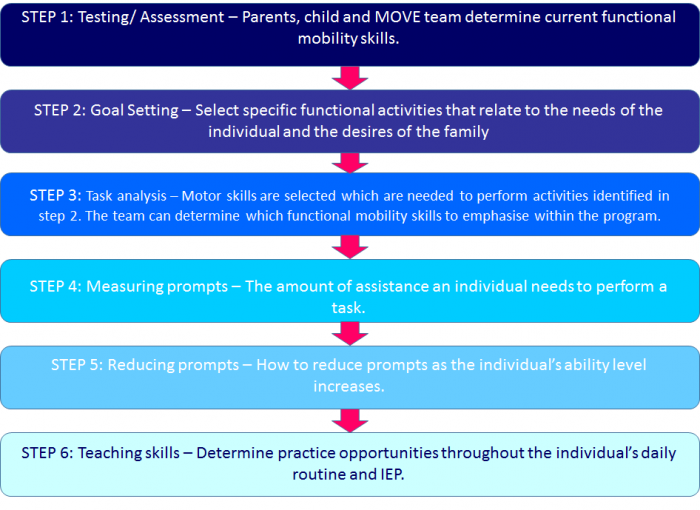

In the 1980’s, Linda Bidabe designed the Movement Opportunities Via Education (MOVE) program. The program was designed, as it was being found that pupils with severe disability were leaving school with less skills than when they first attended. The emphasis of the program is to develop functional and meaningful outcomes for the individual utilising current theories of motor development and activity based programs (Kern County Superintdent of Schools, 1990). The program has been developed to support those with differing levels of abilities and in a multitude of different settings. A top-down Motor milestone assessment is used; therefore concentrating on the current abilities of the child.

From the simpler tasks to a more complex tasks, individuals are taught skills to optimise their independent functioning (van der Putten, Vlaskamp, Reynders, & Nakken, 2005). Activities relate to sitting, standing, transferring and walking. By using a collaborative team approach and a six step method, MOVE develops goals and priority goals to implement an intervention (Bidabe, Barnes, & Whinnery, 2001). The six steps of MOVE are as follows:

CEREBRAL PALSY AND MAINSTREAM SCHOOLING

“BEING A PART, NOT APART”

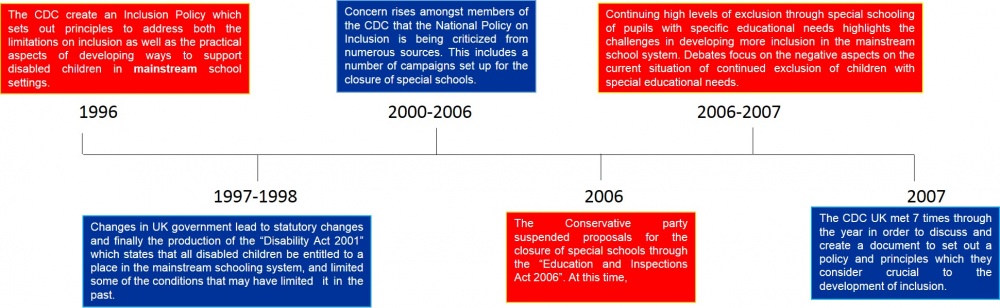

The Council for Disabled Children (CDC) is an blanket term for a group of organizations that hold a range of perspectives on inclusion. It is a group of council members with diverse backgrounds including professionals, parent representatives and representatives of disabled people. The CDC’s main sector is based in England, but with links to other UK nations. The CDC celebrates what is working well in the education system and family life for children and young people with disabilities and demonstrates this through their policies (CDC 2014).

(CDC, 2014)

INCLUSION POLICIES

[edit | edit source]

The CDC, Inclusion Scotland and Learning and Teaching Scotland (LTS) are three organisations which support and promote the inclusion of children with disabilities into mainstream schooling. The CDC believes that special schools should hold a close link to the mainstream setting so that one day all children are included into the mainstream schooling system (CDC, 2014).

“With the proper support and encouragement, many more disabled children could be included into the mainstream school system” (CDC 2014, p.5).

LTS agrees, stating that;

"All children and young people will have access to mainstream education unless there are exceptional circumstances" (LTS 2014, p. 7).

The CDC believe that by promoting inclusion, both disabled children and their non-disabled peers benefit (CDC, 2014). Separating children with disability does not prepare them for life in a predominantly non-disabled world (ISDPO 2014, p.4). It is believed disabled individuals are happy to attend mainstream schools, as it allows both them and non-disabled individuals for later in life (ISDPO 2014, p.4-5). All the while, The Education Act (2004) ensures those who require extra support receive it (LTS, 2014).

Creating and Maintaining an Inclusive Community; “School is a Place for Everyone”[edit | edit source]

The Education Scotland Act 2004 states that School must be considered a place where;

◘ certain principles are the heart of all that happens

◘ each and every individual has a value and worth

◘ people feel they belong

◘ people learn

◘ everyone can achieve

◘ responsibility is shared

◘ there is no exclusion by expectation

◘ prejudice and discrimination are countered and their negative effects greatly diminished” (LTS 2014, p.16))

WHAT CAN MAINSTREAM SCHOOL TEACHERS DO?[edit | edit source]

It is important for teachers to understand that children with CP enjoy the same types of activities and can do the same types of activities that children without CP can (The Nemours Foundation 2014).

The following tips may help mainstream primary school teachers promote inclusivity for students with CP;

★ Allow children with CP more time to travel to and from classes

★ Allow children with CP a longer amount of time in order to complete assessments

★ Ensure your classroom is easy to get around and free of obstacles

★ Understand that children with CP may miss more class time due to medical appointments

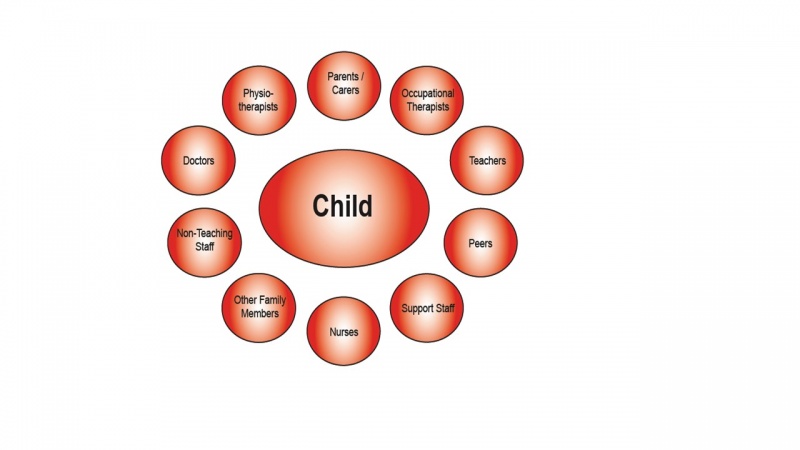

★ Include parents, medical staff, therapists, and the student in order to develop the best education plans for a student with CP

★ Be prepared for possible medical emergencies by planning ahead with parents in case your students with CP need advanced assistance (The Nemours Foundation 2014)

DISABILITY INCLUSION TRAINING FOR THE EDUCATION SECTOR[edit | edit source]

In 2012 Scottish Disability Sport (SDS) received financial backing from both the Scottish government and Education Scotland in order to offer disability inclusion training. The training is aimed at early years and primary teachers, specialist PE teachers, trainee teachers and learning support staff. It is offered at no cost. The training is tailored to encourage disabled children to lead a full and active lifestyle, through inclusion with their non disabled peers (SDS 2012).

Including Children with CP in mainstream physical education lessons[edit | edit source]

A study was done in order to investigate elementary school children with CP’s perceptions on the advantage of and barriers to, attending mainstream physical education classes. The study was conducted through individual interviews with students with CP, teachers and teaching assistants (Hilderley and Rhind 2012).

Three main advantages of CP students attending mainstream physical education classes;

1. Psychological benefits (improved self-esteem/body image)

2. Social Benefits (developing relationships)

3. Physical benefits (improved mobility)

BARRIERS were identified as being;

1. Environmental (appropriate facilities)

2. Organizational (appropriate staff:class size)

3. The disability (wheelchair)

4. Attitudinal (of peers/staff and child)

In conclusion, there is a an obvious need for mainstream school teacher’s to work on promoting the potential advantages and overcoming barriers to the inclusion of students with CP. Additionally, it is clear that this is done most easily through understanding people’s own perceptions on inclusion (Hilderley and Rhind 2012)

REFERENCES[edit | edit source]

COUNCIL FOR DISABLED CHILDREN., 2014. Council for Disabled Children Inclusion Policy [online]. London. [viewed 9 November 2014]. Available from: http://www.councilfordisabledchildren.org.uk/resources/cdcs-resources/inclusion-policy

HILDERLEY, E. and RHIND, D., 2012. Including children with cerebral palsy in mainstream physical education lessons: a case study of student and teacher experiences. Graduate Journal of Sport, Exercise, and Physical Education Research [online]. vol. 1, pp 1-15 [viewed 30 October 2014] Available from: http://www.worcester.ac.uk/gjseper/documents/Children_with_cerebral_palsy_in_mainstream_physical_ed_case_study_student_teacher_experiences.pdf

INCLUSION SCOTLAND DISABLED PEOPLE’S ORGANISATION., 2014. A Vision for an Inclusive Scotland [online]. Edinburgh. [viewed 1 November 2014]. Available from: http://www.inclusionscotland.org/documents/AVisionBooklet.pdf

LEARNING AND TEACHING SCOTLAND., 2014. Focusing on Inclusion: a Paper for Professional Reflection [online]. 3rd ed. Scotland. [viewed 7 November 2014]. Available from: http://www.educationscotland.gov.uk/images/FocusingOnInclusion_tcm4-342924.pdf

SCOTTISH DISABILITY SPORT., 2014. Successful disability inclusion training for the education sector [online]. [viewed 2 November 2014]. Available from: http://www.scottishdisabilitysport.com/sds/index.cfm/news/latest-news1/successful-disability-inclusion-training-for-the-education-sector/

THE NEMOURS FOUNDATION., 2014. Cerebral Palsy Special Needs Fact Sheet [online]. [viewed 2 November 2014]. Available from: http://kidshealth.org/parent/classroom/factsheet/cp-factsheet.html

EDUCATION AND LEARNING., 2014. Types of School [online]. [Viewed 16 November 2014]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/types-of-school/overview.

THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES. (2010). Equality Act 2010. [online]. [Viewed 16 November 2014]. Available from: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/part/6/enacted.

DEBENHAM, L. . (2012). The Special Education Needs and Disability Act. . [online]. [Viewed 8 November 2014]. Available From: http://www.aboutlearningdisabilities.co.uk/special-educational-needs-disability-act.html.

KERN COUNTY SUPERINTENDENT OF SCHOOLS. (1990). MOVE: Mobility Opportunities Via Education. Bakersfield, CA, Little green press. VAN DER PUTTEN, A., VLASCAMP, C., REYNDERS, K & NAKKEN, H. (2005). Reducing support: research into the effects of movement-oriented activities on the level of support when performing movement skills for children with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. Postbus, Groningen: Stichting kinderstudies.

BIDABE, L., BARNES, B., WHINNERY, W. (2001). MOVE: Raising expectations for individuals with severe disabilities. Physical Disabilities: Education and Related services. 19 (2), 31-48.

BARNES, B & WHINNERY, W. (2002). Effects of functional mobility skills training for young students with physical disabilities. Exceptional Children. 68(3). 313-324.

==

Insert non-formatted text here

'Bold text ]]Link title