Assessment Before Moving and Handling: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

|Blood Presure | |Blood Presure | ||

|Oxygen Saturation | |Oxygen Saturation | ||

| | |Unpredictable | ||

|Devices | |Devices | ||

|Hearing | |Hearing | ||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

| | | | ||

|Depression | |Depression | ||

| | |Medication | ||

|Understanding | |Understanding | ||

|Decision Making | |Decision Making | ||

Revision as of 00:24, 8 June 2023

Original Editors - Naomi O'Reilly, Vidya Acharya

Top Contributors - Naomi O'Reilly, Ewa Jaraczewska, Jess Bell, Tarina van der Stockt, Kim Jackson and Carina Therese Magtibay

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Moving and handling people is a part of everyday working life and a core activity for most rehabilitation professionals. Patients with difficulty moving independently may require assistance, ranging from verbal encouragement to using electric hoisting equipment. Every situation involving moving and handling will present varying risk levels to the patient and the rehabilitation professional.

Decisions about the most appropriate rehabilitation techniques and interventions are made following an individual patient risk assessment in accordance with professional guidelines for moving and handling. While adequate training is a key element of safe moving and handling, having a clear understanding of the range of factors that can impact moving and handling are also key to providing a safe environment.

This article will explore the factors that directly impact the patient and assist the healthcare professional in ensuring the patient's safety when moving and handling.

| Physical Status | Cardiovascular Status | Respiratory Status | Emotional Status | Medical Status | Communication | Cognitive Status | Sensory Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | Heart Rate | Respiratory Rate | Resistive | Diagnosis | Speech | Memory | Sensation |

| Height | Blood Presure | Oxygen Saturation | Unpredictable | Devices | Hearing | Judgement | Hearing |

| Range of Motion | Breathing Pattern | Unco-operative | Pain | Vision | Concentration | Vision | |

| Strength | Depression | Medication | Understanding | Decision Making | |||

| Balance | Agression | Fatigue | Language | Impulsivity | |||

| Coordination | Confused | Time of Day | Culture | Ability Follow Instructions | |||

| Tone | Agitated | ||||||

| Skin Integrity | |||||||

| Body Awareness | |||||||

| Depth Perception |

Communication[edit | edit source]

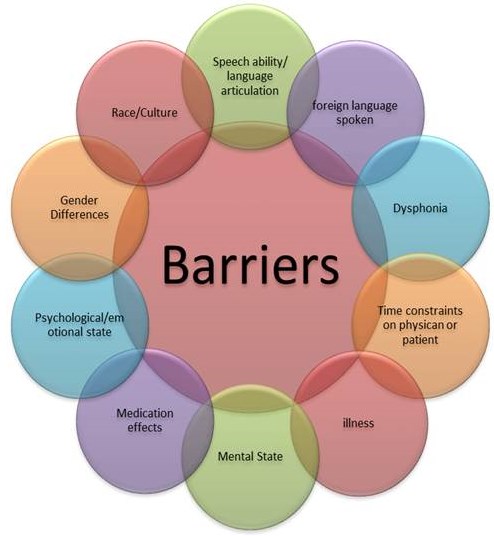

Communication is a "two-way process of reaching mutual understanding, in which participants exchange information, news, ideas and feelings and create and share meaning. [1] Transferring information can take the form of verbal communication, such as speech and listening, or non-verbal communication, including body language, eye contact, gestures and expressions. [2] Effective clinical communication skills can improve health outcomes and are important to high-quality healthcare.[3]

Communication can impact healthcare professionals' interaction with patients in various ways, with poor communication leading to adverse patient outcomes and reduced compliance with treatment. Conversely, effective communication leads to productive health changes and higher satisfaction among patients.[4]

The communication cycle can be affected by the following:[5]

For patient:

- Language barriers

- Cultural barriers

- Physical and cognitive impairments, including hearing or vision loss

- Environmental factors including a noisy environment or lack of privacy [6]

- Medication effect

- Person's emotional state, i.e. anxiety, pain and physical discomfort

For healthcare professionals:[7]

- Time management

- Inability to build rapport with patients

- High patient load

- Healthcare professional's emotional state, i.e. stress and anxiety

- Knowledge insecurity, lack of specialised training

Prior to any moving and handling, it is vital to assess whether your patient has any problem expressing themselves or understanding your request and identifying any specific communication needs that may be required, including access to Interpreters or assistive technology. Where you have specific concerns concerning communication, further referral to speech and language therapy or psychology may also be warranted to better understand communication difficulties and their causes.

Cognitive Status[edit | edit source]

Cognitive status is crucial in determining if a patient can safely participate in assessment, positioning, transferring and mobilising a patient. [8] When considering cognition, it is important to explore whether the patient has trouble concentrating, understanding instructions, performing tasks in the wrong order or missing out or forgetting elements of the task.

Patients' cognitive status assessment is a quick and simple method to determine their orientation at the time of initial assessment and during any manual handling tasks and provide some basic information on their ability to answer questions and possibly follow instructions.[9]

Assessing orientation can be accomplished by the following:

- Asking the patient a series of standard questions:

- Person - "Can you tell me your name and date of birth?

- Place - "Can you tell me where you are right now?" or "Can you tell me what city we are in?

- Time/Date - "Can you tell me today's date?" or "What day of the week is it?" or "What year is it?

- Situation - "Can you tell me what brought you to the hospital or health centre?" or "What surgery did you have?"

- Administering a Mini-Mental State Examination:

- Used primarily to screen for cognitive impairment in older adults, estimate the severity of cognitive impairment at a given point in time, and assesses a number of subsets of cognitive status including attention, language, memory, orientation, and visuospatial proficiency.[10] [11]

- A Mini Mental State Score of 0 - 17 is interpreted as severe cognitive impairment. It may impact participation in rehabilitation activities. [12]

Emotional Status[edit | edit source]

Emotions are physical and instinctive, instantly prompting bodily reactions to threats, rewards, and everything. [13]

The following signs and symptoms can indicate changes in the patient's emotional status:

- Confusion, agitation or depression

- Euphoria or tearfulness

- Inappropriate behaviour (verbal and/or physical)

- Lack of cooperation during the assessment

When faced with any of these situations, the rehabilitation professional should:

- Liaise with relevant members of the multidisciplinary team to ensure a more comprehensive assessment to determine if any specific factors are impacting emotional status, and/or

- utilise outcome measures like the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS), which is designed to assess the level of alertness and agitated behaviour in critically-ill patients [14]

- A RASS Score between -1 and +1 generally indicates that the patient possesses a level of alertness that will allow them to participate in rehabilitation with minimal risk of adverse effects.[15]

The following resource Assessing Emotional Status - Suggestions of Questions to Ask about a Person with Cognitive Impairment, is a useful tool to support your assessment of cognitive status.

Sensory Status[edit | edit source]

Vision[edit | edit source]

Vision loss can significantly impact the lives of those who experience it. The health consequences of vision loss extend well beyond the eye and visual system. Vision loss has been shown to affect the quality of life (QOL)[16][17], independence[18][19], and mobility and has been linked to falls,[20][21] injury [21][22], and worsened status in domains spanning mental health[23], cognition[24][25], social function, employment, and educational attainment.[26][27]

Assessing vision is a key part of your assessment before moving or handling a patient. The following are examples of assessment questions:

- When did you last have a vision test?

- Do you wear glasses? If so, are your glasses up to date?

- What do you wear your glasses for? e.g. reading/distance/everything [bifocals/varifocals]?

- Have you got your glasses with you?

- Do you have any eye conditions? If so, are you using any prescribed treatment? (e.g. eyedrops for glaucoma)

- Do you see the television clearly at home? Can you describe what is in this picture?

- Are you able to read newspaper print? Medicine labels? Can you please read the following paragraph...

The following resources can assist with vision assessment by healthcare professionals:

- "Look out! Bedside Vision Check for Falls Prevention" by the Royal College of Physicians provides a detailed plan with visual resources for completing a bedside vision assessment to reduce the risk of falls during moving and handling activities.

- VISIBLE resource (Vision Screening to Improve Balance & Prevent Falls) created by Health Innovation Network (HIN) South London provides a simple stepped approach to implement vision screening in community settings.

Hearing[edit | edit source]

Hearing loss has been associated with altered balance [28] and an increased risk of falls [29][30][31], particularly within the older person population. [32] Some emerging evidence suggests hearing aid may improve postural control in individuals with hearing loss, which may potentially reduce fall risk, although further research is needed.[32][33]

Hearing is assessed during the subjective assessment to rule out any hearing difficulties present. Basic questions as part of the moving and handling assessment should include the following:

- Do you wear hearing aids?

- Are your hearing aids in and switched on?

If the patient is not using a hearing aid, a healthcare professional should consider whether they may benefit from them but recognise that during the assessment, difficulties in concentration or attention may present similarly to hearing loss in some individuals.

Vital Signs[edit | edit source]

Vital signs are measurements of the body's most basic functions, which can detect or monitor medical problems. Typically vital signs monitored by rehabilitation professionals provide information on the cardiovascular and respiratory status and include the following:

- pulse and heart rate

- blood pressure

- respiratory rate

- oxygen saturation

These vital signs can be measured to establish goals and assess a patient's response to activity. Clinical indicators that highlight the need for an assessment of vital signs include dyspnea, hypertension, fatigue, syncope, chest pain, irregular heart rate, cyanosis, intermittent claudication, nausea, diaphoresis, and pedal oedema.

Cardiovascular Status[edit | edit source]

Pulses and Heart Rate[edit | edit source]

Pulse rate is the wave of blood in the artery created by contraction of the left ventricle during a cardiac cycle. The most common sites for measuring the peripheral pulses are the radial pulse, ulnar pulse, brachial pulse in the upper extremity, and the posterior tibialis or the dorsalis pedis pulse, as well as the femoral pulse in the lower extremity. Clinicians also measure the carotid pulse in the neck. In day-to-day practice, the radial pulse is the most frequently used site for checking the peripheral pulse, where the pulse is palpated on the radial aspect of the forearm, just proximal to the wrist joint.

- Rate:

- The normal range used in an adult is between 60 to 100 beats /minute, with rates above 100 beats/minute and below 60 beats per minute, referred to as tachycardia and bradycardia, respectively. Changes in the pulse rate, along with changes in respiration, are called sinus arrhythmia. In sinus arrhythmia, the pulse rate becomes faster during inspiration and slows down during expiration.

- Rhythm:

- Assessing whether the rhythm of the pulse is regular or irregular is essential. The pulse could be regular, irregular, or irregularly irregular. Irregularly irregular pattern is more commonly indicative of processes like atrial flutter or atrial fibrillation.

- Volume:

- Assessing the volume of the pulse is equally essential. A low-volume pulse could indicate inadequate tissue perfusion, a crucial indicator of indirect prediction of the patient's systolic blood pressure.[34]

- Symmetry:

- Checking for symmetry of the pulses is important as asymmetrical pulses could be seen in conditions like aortic dissection, aortic coarctation, Takayasu arteritis, and subclavian steal syndrome.

- Amplitude and Rate of Increase:

- Low amplitude and low rate of increase could be seen in conditions like aortic stenosis, besides weak perfusion states. High amplitude and rapid rise can indicate aortic regurgitation, mitral regurgitation, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.[35]

If the heart rate increases or decreases significantly above normal expectations during any movement and the patient experiences any shortness of breath, chest pain, or faints, then the further progression of the activity should be stopped at that time. Action: Stop the activity, return the patient to rest, and monitor HR until it stabilises.

Blood Pressure[edit | edit source]

Blood pressure is the force of circulating blood on the walls of the arteries, mainly in large arteries of the systemic circulation. Blood pressure incorporates two measurements:

- Systolic Pressure

- Describes the maximum pressure in the large arteries when the heart contracts to propel blood through the body.

- Measured when the heartbeats

- Diastolic Pressure

- Describes the lowest pressure within the large arteries when the heart relaxes between beats.

- Measured between heartbeats.

Blood pressure is traditionally assessed using auscultation with a mercury-tube sphygmomanometer measured in millimetres of mercury and expressed in terms of the systolic pressure over diastolic pressure, e.g. 120/60.[36] However, semiautomated and automated devices that use the oscillometry method, which detects the amplitude of the blood pressure oscillations on the arterial wall, have become widely used in daily clinical practice. The brachial artery is the most common site for BP measurement.

The usual BP response to exercise in healthy individuals is an initial rise in systolic BP, followed by a linear increase as exercise intensity increases. The diastolic BP tends to remain stable or only slightly increase at higher levels of exercise intensity.

To determine if it is safe to continue with mobilisation, recent changes in BP are most relevant. An acute increase or decrease in BP of at least 20% indicates haemodynamic instability and is likely to delay mobilisation. There are two important things to consider:

An excessive rise in systolic or diastolic BP during mobilisation, especially if prolonged, may restrict mobility progress.

Failure of systolic BP to increase or a sustained fall in BP during mobilisation may reflect orthostatic intolerance or an inability of the patient’s cardiovascular system to meet the increased demands of the imposed task. Action: stop mobilisation or modify the task to a less demanding level where BP can be maintained at appropriate levels.

| Reduce Accuracy | Systolic | Diastolic |

|---|---|---|

| Hypotension | <90 | <60 |

| Normal | 90 - 129 | 60 - 79 |

| Hypertension; Stage 1 | 130 - 139 | 80 - 89 |

| Hyoertension: Stage 2 | 140 - 179 | 90 - 109 |

| Hypertension: Critical | >180 | >110 |

Respiratory Status[edit | edit source]

"Work of breathing is the amount of energy or O2 consumption needed by the respiratory muscles to produce enough ventilation and respiration to meet the metabolic demands of the body".[37]

Respiratory Rate[edit | edit source]

The respiratory rate, the number of breaths per minute, is the one breath to each air movement in and out of the lungs. The average adult's normal breathing rate is about 12 to 20 beats per minute. The respiratory rate depends on the child's age in the paediatric age group.

Evidence suggests that respiratory rate is one of the first signs to change when the body has a problem. It is a key element to closely monitor a patient's response to any rehabilitation intervention.

- Rates:

- Rates higher or lower than expected are tachypnea and bradypnea, respectively.

- Tachypnea: respiratory rate of more than 20 beats per minute

- Causes: effect of exercise, emotional changes, pregnancy, and pathological conditions like pain, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, and asthma.

- Bradypnea: ventilation less than 12 breaths/minute

- Causes: worsening of any underlying respiratory condition leading to respiratory failure or due to usage of central nervous system depressants like alcohol, narcotics, benzodiazepines, or metabolic derangements.

- Apnea: complete cessation of airflow to the lungs for a total of 15 seconds

- Causes: cardiopulmonary arrests, airway obstructions, the overdose of narcotics and benzodiazepines.

- Depth of Breathing:

- Hyperpnea is described as an increase in the depth of breathing.

- Hyperventilation is an increase in the rate and depth of breathing

- Hypoventilation describes the decreased rate and depth of ventilation.

- Depth of breathing involves what muscle groups they are using—for example, the sternocleidomastoid (accessory muscles) and abdominal muscles—the movement of the chest wall in terms of symmetry.

- The inability to speak in full sentences or increased effort to speak is an indicator of discomfort when breathing.[38]

Oxygen Saturation[edit | edit source]

Oxygen saturation is a crucial measure of how well the lungs are working and is considered an essential element in assessing and monitoring a patient for positioning, transferring or mobilising. Oxygen saturation refers to the percentage of oxygen circulating in an individual's blood. Pulse oximetry is a painless, noninvasive method of measuring the saturation of oxygen (SpO2) in a person’s blood.[39] Most pulse oximeters are accurate to within 2% to 4% of the actual blood oxygen saturation level, which means that a pulse oximeter reading may be anywhere from 2% to 4% higher or lower than the actual oxygen level in arterial blood, in particular when oxygen saturation is below 90%.[40] For example, a 92% oxygen saturation on the pulse oximeter can actually be between 88 to 96% depending on the accuracy of the specific pulse oximeter.

| Reduce Accuracy | Increase Accuracy |

|---|---|

| Cold Hands | Warm Up Skin |

| Poor Circulation or Low Perfusion State | Apply Topical Vasodilator |

| Wearing Artificial Nails | Hand Below Level of Heart |

Wearing Nail Polish

|

Probe Location

|

Very Low Oxygen Saturation

|

Probe Type

|

Skin Pigment

|

Probe Size

|

| Skin Thickness | |

| Anaemia | |

Motion Artefact

|

|

| Intravascular Dyes | |

| Smoking |

Breathing Pattern[edit | edit source]

There are many conditions which are based on the variation in the pattern of breathing:[43]

- Biot’s respiration is a condition where there are periods of increased rate and depth of breathing, followed by periods of no breathing or apnea.

- Cheyne-Stokes respiration is a peculiar pattern of breathing where there is an increase in the depth of ventilation followed by periods of no breathing or apnea.

- Kussmaul’s breathing refers to the increased depth of ventilation, although the rate remains regular.

- Orthopnea refers to difficulty in respiration occurring on lying horizontally but improves when the patient sits up or stands.

- Paradoxical ventilation refers to the inward movement of the abdominal or chest wall during inspiration and outward movement during expiration, seen in cases of diaphragmatic paralysis, muscle fatigue, and trauma to the chest wall.

Environment[edit | edit source]

The environment means considering the area in which you are completing tasks that require moving and handling of the patient and looking at how this could make the task unsafe. Generally, an environmental assessment identifies any problems and offers solutions to hazardous areas within that specific environment. [44]

Questions to consider during the assessment prior to moving and handling include:

- Are there any space constraints?

- Is the floor slippery or uneven?

- Is there sufficient lighting?

- Are there any trip hazards?

- Does the patient have any attachments?

Attachments[edit | edit source]

The patient will have various attachments in the hospital setting, including ECG leads, arterial & venous lines, central venous catheters, urinary catheters, pulse oximetry, and underwater sealed drain. Prior to performing and moving or handling tasks, consult with the nursing staff to find out which attachments can be safely disconnected for the activity. Attachments that provide vital physiological data, like the ECG leads and pulse oximeters, often must remain connected for safety, particularly when the patient is moved for the first time. Care must be exercised during mobilisation to prevent any attachments from being dislodged. It is important to remove or avoid kinks and twists in the lines and watch out for drains, e.g. urinary catheter or chest drains and ensure they remain below the level of tube insertion in the body. It is important to check the drain before and after treatment to ensure no excessive drainage or pressure swing in the water seal level, which could impact the performance of the drains.

Other Factors[edit | edit source]

Pain[edit | edit source]

Pain can be a significant barrier that must be addressed during any assessment before moving and handling. To address the pain, the healthcare provided should do one or all of the following:

- Assess the pain: [43]

- When assessing pain, it is important to recognise the differences between acute and persistent pain and the implications for assessing and managing the patient. Pain is a subjective experience, and

- Self-report of pain is the most reliable indicator of a patient’s experience.

- If a patient possesses the given cognition and communication abilities, pain should be assessed using a standard self-report tool such as a Numeric Pain Rating Scale or Visual Analogue Scale.

- Many critical care patients are not appropriate for these scales due to factors such as sedation or mechanical ventilation. In these instances, several objective measures of pain have been found to be valid and effective for critically ill patients.

- Always assess pain at the beginning of any physical assessment to determine the patient’s comfort level and the potential need for pain comfort measures prior to moving the patient.

Pain Assessment Tools[edit | edit source]

Critical Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT): CPOT is an 8-point measure that utilizes 4 basic behaviours (facial expression, body movement, muscle tension, and ventilator compliance (intubated patients) or vocalizations (extubated patients) to provide an assessment of pain.[43]

Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS): The BPS is intended for use in patients receiving mechanical ventilation. The BPS is a 12-point scale that uses 3 basic behaviours (facial expression, upper extremity movement, and ventilator compliance) to assess pain.[43]

Medication[edit | edit source]

Rehabilitation professionals should be aware of the patient's medications, as these can impact the patient's safety during manual handling tasks. While medication management is not the role of most rehabilitation professionals, understanding the potential impact of some medications can be very valuable. Assessment and rehabilitation interventions should be timed to coincide with medication peak effectiveness.[45]

The following classes of drugs, in particular, can increase the risks of falls as they can affect the brain, heart and circulatory system:

- Drugs Acting on the Central Nervous System, e.g. Psychotropic Drugs

- Drugs or other substances that affect the brain's work can cause changes in mood, thoughts, perception, behaviour, levels of alertness, reflexes, reaction times, muscle tone, balance, etc.

- Drugs Acting on the Heart and Circulatory System

- Drugs that are used to treat different heart disorders (such as congestive heart failure, angina, or arrhythmia) or diseases of the vascular system (e.g., hypertension) can cause hypotension, orthostatic hypotension, syncope, bradycardia, muscle weakness or muscle spasms secondary to hyponatremia

- Drugs Acting on Glycemic Control

- Hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia have been correlated with an increased risk for falls in the hospitalised population.

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

These safety assessments should be considered before and during any moving or handling of the patients to maximise safety and minimise risk for both the patient and any rehabilitation professional involved. However, it is important to recognise that we do not necessarily have to conduct each assessment during every assessment. Instead, we must carefully consider the patient, their condition and their environment and use our clinical reasoning and judgement to choose the most appropriate assessments to ensure their safety during moving and handling tasks.

Resources[edit | edit source]

The Handling of People A systems Approach

Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care

Patient Handling and Mobility Assessments 2nd Edition

Guidance on Manual Handling in Physiotherapy (4th edition)

Guidance for Physiotherapists - Paediatric Manual Handling

References [edit | edit source]

- ↑ Zafar Z. Communication. Available from https://medium.com/@zahrazafarullah786/communication-3d612d633daf. [last access 26.05.2023]

- ↑ Mata ÁNS, de Azevedo KPM, Braga LP, de Medeiros GCBS, de Oliveira Segundo VH, Bezerra INM, Pimenta IDSF, Nicolás IM, Piuvezam G. Training in communication skills for self-efficacy of health professionals: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health. 2021 Mar 6;19(1):30.

- ↑ Iversen ED, Wolderslund MO, Kofoed PE, Gulbrandsen P, Poulsen H, Cold S, Ammentorp J. Codebook for rating clinical communication skills based on the Calgary-Cambridge Guide. BMC Med Educ. 2020 May 6;20(1):140.

- ↑ Cannity KM, Banerjee SC, Hichenberg S, Leon-Nastasi AD, Howell F, Coyle N, Zaider T, Parker PA. Acceptability and efficacy of a communication skills training for nursing students: Building empathy and discussing complex situations. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021 Jan;50:102928.

- ↑ Amoah VMK, Anokye R, Boakye DS, Gyamfi N, Lee A (Reviewing Editor). Perceived barriers to effective therapeutic communication among nurses and patients at Kumasi South Hospital, Cogent Medicine. 2018;5:1.

- ↑ Al-Kalaldeh M, Amro N, Qtait M, Alwawi A. Barriers to effective nurse-patient communication in the emergency department. Emerg Nurse. 2020;28(3):29-35.

- ↑ Albahri AH, Abushibs AS, Abushibs NS. Barriers to effective communication between family physicians and patients in the walk-in centre setting in Dubai: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):637.

- ↑ Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Thompson JL, Pun BT, et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(14):1306-16.

- ↑ Fruth SJ. Fundamentals of the Physical Therapy Examination: Patient Interview and Test & Measures. 2nd Ed. Burlington: Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2018.

- ↑ Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975 Nov; 12(3):189-98.

- ↑ Sleutjes DK, Harmsen IJ, van Bergen FS, Oosterman JM, Dautzenberg PL, Kessels RP. Validity of the Mini-Mental State Examination-2 in Diagnosing Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia in Patients Visiting an Outpatient Clinic in the Netherlands. Alzheimer's disease and associated disorders. 2020 Jul;34(3):278.

- ↑ Faber RA. The neuropsychiatric mental status examination. Semin Neurol. 2009 Jul;29(3):185-93.

- ↑ Farnsworth B. How to measure emotions and feelings (and their differences). Available from https://imotions.com/blog/learning/best-practice/difference-feelings-emotions/. [last access 26.05.2023]

- ↑ Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, Brophy GM, O'Neal PV, Keane KA, Tesoro EP, Elswick RK. The Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2002 Nov 15;166(10):1338-44.

- ↑ Green M, Marzano V, Leditschke IA, Mitchell I, Bissett B. Mobilization of intensive care patients: a multidisciplinary practical guide for clinicians. J Multidiscip Healthc 2016; 25(9): 247-56.

- ↑ Chaudry I, Brown GC, Brown MM. Medical student and patient perceptions of quality of life associated with vision loss. Can J Ophthalmol. 2015 Jun;50(3):217-24.

- ↑ Cheng HC, Guo CY, Chen MJ, Ko YC, Huang N, Liu CJL. Patient-reported vision-related quality of life differences between superior and inferior hemifield visual field defects in primary open-angle glaucoma. JAMA Ophthalmology. 2015;133(3):269–275.

- ↑ Christ SL, Zheng DD, Swenor BK, Lam BL, West SK, Tannenbaum SL, Muñoz BE, Lee DJ. Longitudinal relationships among visual acuity, daily functional status, and mortality: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014 Dec;132(12):1400-6.

- ↑ Haymes SA, Johnston AW, Heyes AD. Relationship between vision impairment and ability to perform activities of daily living. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2002 Mar;22(2):79-91.

- ↑ Crews JE, Chiu-Fung Chou CF, Stevens JA, Saadine JB. Falls among persons aged > 65 years with and without severe vision impairment—United States, 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2016a;65(17):433–437.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 de Boer MR, Pluijm SM, Lips P, Moll AC, Volker-Dieben HJ, Deeg DJ, van Rens GH. Different aspects of visual impairment as risk factors for falls and fractures in older men and women. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2004;19(9):1539–1547.

- ↑ Coleman AL, Cummings SR, Ensrud KE, Yu F, Gutierrez P, Stone KL, Cauley JA, Pedula KL, Hochberg MC, Mangione CM; Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. Visual field loss and risk of fractures in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009 Oct;57(10):1825-32.

- ↑ Garaigordobil M, Bernarás E. Self-concept, self-esteem, personality traits and psychopathological symptoms in adolescents with and without visual impairment. Spanish Journal of Psychology. 2009;12(01):149–160.

- ↑ Pham TQ, Kifley A, Mitchell P, Wang JJ. Relation of age-related macular degeneration and cognitive impairment in an older population. Gerontology. 2006;52(6):353–358.

- ↑ Rogers MA, Langa KM. Untreated poor vision: a contributing factor to late-life dementia. Am J Epidemiol. 2010 Mar 15;171(6):728-35.

- ↑ Bibby SA, Maslin ER, McIlraith R, Soong GP. Vision and self-reported mobility performance in patients with low vision. Clinical and Experimental Optometry. 2007;90(2):115–123.

- ↑ Brown JC, Goldstein JE, Chan TL, Massof R, Ramulu P; Low Vision Research Network Study Group. Characterizing functional complaints in patients seeking outpatient low-vision services in the United States. Ophthalmology. 2014 Aug;121(8):1655-62.e1.

- ↑ Lubetzky AV. Balance, falls, and hearing loss: is it time for a paradigm shift? JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 2020 Jun 1;146(6):535-6.

- ↑ Deandrea S, Lucenteforte E, Bravi F, Foschi R, La Vecchia C, Negri E. Risk factors for falls in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2010 Sep;21(5):658-68.

- ↑ Gopinath B, McMahon CM, Burlutsky G, Mitchell P. Hearing and vision impairment and the 5-year incidence of falls in older adults. Age Ageing. 2016 May;45(3):409-14.

- ↑ Jiam NT, Li C, Agrawal Y. Hearing loss and falls: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2016 Nov;126(11):2587-2596.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Riska KM, Peskoe SB, Kuchibhatla M, Gordee A, Pavon J, Kim SE, West JS, Smith SL. Impact of hearing aid use on falls and falls-related injury: Health and Retirement Study Results. Ear and hearing. 2022 Mar;43(2):487.

- ↑ Ernst A, Basta D, Mittmann P, Seidl RO. Can hearing amplification improve presbyvestibulopathy and/or the risk-to-fall ? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021 Aug;278(8):2689-2694.

- ↑ Hill RD, Smith RB III. Examination of the Extremities: Pulses, Bruits, and Phlebitis. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd edition. Boston: Butterworths; 1990. Chapter 30. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK350/

- ↑ Sapra A, Malik A, Bhandari P. Vital Sign Assessment. [Updated 2022 May 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553213/ [last access 28.05.2023]

- ↑ Dictionary of cancer terms. Blood pressure. National Cancer Institute. Available from https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/blood-pressure [last access 28.05.2023]

- ↑ Dekerlegand RL, Cahalin LP, Perme C. Chapter 26 - Respiratory Failure. Editor(s):Cameron MH, Monroe LG. In: Physical Rehabilitation, W.B. Saunders, 2007: Pages 689-717.

- ↑ Rolfe S. The importance of respiratory rate monitoring. British Journal of Nursing. 2019 Apr 25;28(8):504-8.

- ↑ Hafen B, Sharma S. Oxygen Saturation. [Updated 2021 Aug 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan- [cited 2022 Oct 15]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525974/

- ↑ Jubran A. Pulse Oximetry. Critical Care. 1999 Apr;3:1-7.

- ↑ Hafen B, Sharma S. Oxygen Saturation. [Updated 2021 Aug 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan- [cited 2022 Oct 15]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525974/

- ↑ American Thoracic Society. Pulse-oximetry. Available from https://www.thoracic.org/patients/patient-resources/resources/pulse-oximetry.pdf [last access 28.05.2023]

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 Kotfis K, Zegan-Barańska M, Szydłowski Ł, Żukowski M, Ely EW. Methods of pain assessment in adult intensive care unit patients - Polish version of the CPOT (Critical Care Pain Observation Tool) and BPS (Behavioral Pain Scale). Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther 2017; 49(1): 66-72.

- ↑ Pighills AC, Torgerson DJ, Sheldon TA, Drummond AE, Bland JM. Environmental assessment and modification to prevent falls in older people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2011 Jan;59(1):26-33.

- ↑ Stiller K. Safety issues should be considered when mobilizing critically ill patients. Critical care clinics. 2007 Jan 1;23(1):35-53.