An Introduction to Red Flags in Serious Pathology: Difference between revisions

m (Added image) |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

== Alternative Approach for Clinical Practice == | == Alternative Approach for Clinical Practice == | ||

Recent research by Finucane et al focused on creating a framework for clinicians which encourages them to consider the context of the red flag and then to clinically reason if action is necessary.<ref name=":3">Finucane L, Selfe J, Mercer C, Greenhalgh S, Downie A, Pool A et al. An evidence informed clinical reasoning framework for clinicians in the face of serious pathology in the spine course slide. Physioplus 2020. </ref> | Recent research by Finucane et al focused on creating a framework for clinicians which encourages them to consider the context of the red flag and then to clinically reason if action is necessary.<ref name=":3">Finucane L, Selfe J, Mercer C, Greenhalgh S, Downie A, Pool A et al. An evidence informed clinical reasoning framework for clinicians in the face of serious pathology in the spine course slide. Physioplus 2020. </ref> | ||

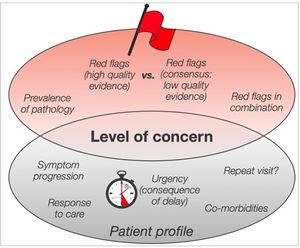

==== Level of Concern ==== | ==== Level of Concern ==== | ||

The level of concern is considered. The framework encourages clinicians to not simply rely on one red flag, but rather to consider the context of the patient and the context of the red flag/s, including symptom progression and co-morbidities.<ref name=":3" /> | The level of concern is considered. The framework encourages clinicians to not simply rely on one red flag, but rather to consider the context of the patient and the context of the red flag/s, including symptom progression and co-morbidities.<ref name=":3" />[[File:Red Flag Framework Level Concern.JPG|thumb|300x300px|Finucane L. Level of concern - an Introduction to red flags in serious pathology slide. Physioplus 2020.|center]] | ||

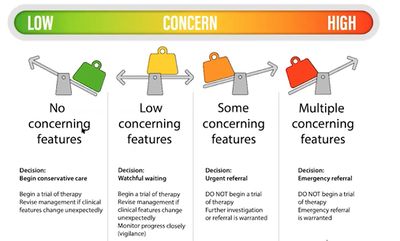

==== Decision ==== | ==== Decision ==== | ||

| Line 46: | Line 44: | ||

If there are more concerning features, the clinician needs to consider their urgency. Is it a medical emergency (eg cauda equina) which requires immediate action or potential metastases, which could wait a few days, but still requires urgent referral?<ref name=":3" /> | If there are more concerning features, the clinician needs to consider their urgency. Is it a medical emergency (eg cauda equina) which requires immediate action or potential metastases, which could wait a few days, but still requires urgent referral?<ref name=":3" /> | ||

[[File:Screen Shot 2020-03-27 at 5.21.56 PM.jpg|center|thumb|Finucane L. Decision Model - an Introduction to Red Flags Course slide. Physioplus 2020]] | [[File:Screen Shot 2020-03-27 at 5.21.56 PM.jpg|center|thumb|Finucane L. Decision Model - an Introduction to Red Flags Course slide. Physioplus 2020|400x400px]] | ||

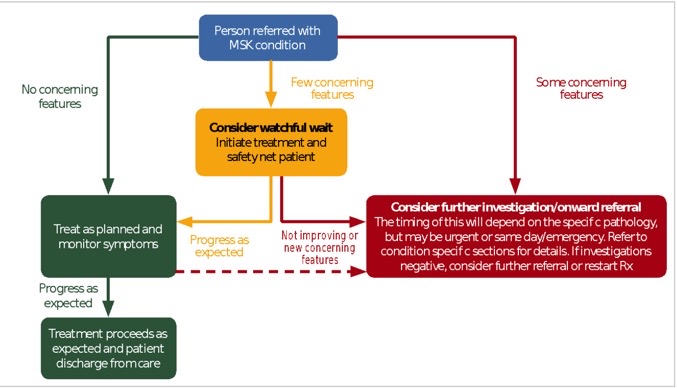

==== Pathway ==== | ==== Pathway ==== | ||

Revision as of 00:32, 28 March 2020

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Only around 1% of all musculoskeletal presentations in primary care will be due to serious pathology.[1] Such pathologies include spinal infection, cauda equina, fracture, malignancy and spondyloarthropathies.

Yet despite the low incidence rates, these conditions should be considered as differential diagnoses when individuals present with back pain - particularly if the patient is not responding in an expected way or is starting to worsen.[1] Identifying serious pathology early on is very important for a number of reasons:

- Prognosis improves with early diagnosis

- Patients tolerate treatment better

- Outcomes are better

- Quality of life is better maintained[1]

However, it can be challenging identifying serious pathologies as they often masquerade as musculoskeletal conditions, particularly in the early stages of disease. As a disease progresses, it becomes easier to identify as patients become systemically unwell.[1]

What are Red Flags?[edit | edit source]

The flag system describes clinical and psychological flags and is comprised of red, orange, yellow, blue and black. Clinical flags are common to many areas of health – for example, red flags are indicators of possible serious pathology such as inflammatory or neurological conditions, structural musculoskeletal damage or disorders, circulatory problems, suspected infections, tumours or systemic disease. If suspected, these require urgent further investigation and often surgical referral.

Red flag screening questions were developed to help detect serious spinal pathology.[1] However, specific red flag questions are not used consistently across guidelines and there is little evidence to support their use.[2][3] Moreover, there are 163 different items that could be considered to be red flags, all of which are subject to interpretation.[4] Because of these factors, the benefit of using red flags has been questioned.[4] Yet a clinician still needs to determine if a patient’s presenting condition is suitable for conservative management or if a referral is necessary. Thus, despite a lack of consensus, red flags are still considered the most reliable clinical indicator of potential serious pathology.[4]

Common Red Flags[edit | edit source]

- Age over 50 years

- Progressive symptoms

- Thoracic pain

- Past history of cancer

- Weight loss

- Drug abuse

- Night pain

- Systemically unwell (fever)

- Night sweats[1]

Evidence for Red Flags[edit | edit source]

Certain red flags have been shown to have good accuracy. For instance, recent trauma and age >50 is associated with vertebral fracture.[2] Similarly, a “history of cancer” and “strong clinical suspicion” have empirical evidence of high diagnostic accuracy for malignancy.[5]

However, as mentioned above, red flags generally have poor diagnostic accuracy[2] and there is a lack of consensus in guidelines as to which red flags should be used[6] or when clinicians should act.[1]

Some guidelines recommend that patients should be referred on if one red flag is identified.[1] However, at least 80% of patients will have at least one red flag. Acting on a single red flag alone would, therefore, lead to many unnecessary investigations.[1] Thus, it is essential to consider the patient’s entire history. Clinicians must ask for enough detail to understand the context behind the answers. Examples of this include:

- when there is a history of cancer, it is important to enquire where the original cancer was: breast, prostate and lung would heighten the index of suspicion of metastases in the spine.[1]

- when there is weight loss, as unexplained weight loss is a cause for concern. However, if a patient has been on a diet or exercising more, weight loss is to be expected. Weight loss could also be due to pain or certain medications suppressing a patient’s appetite.[1]

- when there is night pain - many patients with back pain will complain of night pain. It is therefore important to find out more about the quality of this pain. A patient who is able to get back to sleep will not generate the same level of suspicion as a patient who cannot get back to sleep or has to get up to sit in a chair to get back to sleep.[1]

Alternative Approach for Clinical Practice[edit | edit source]

Recent research by Finucane et al focused on creating a framework for clinicians which encourages them to consider the context of the red flag and then to clinically reason if action is necessary.[7]

Level of Concern[edit | edit source]

The level of concern is considered. The framework encourages clinicians to not simply rely on one red flag, but rather to consider the context of the patient and the context of the red flag/s, including symptom progression and co-morbidities.[7]

Decision[edit | edit source]

The clinician needs to decide if there is a level of concern. If there is none, management can begin. If there is some concern, the clinician could consider a trial treatment but will need to monitor the patient over time and revise the management if necessary. Red flags should be regularly considered and re-evaluated. It is not enough to simply consider red flags at the initial assessment.[7]

If there are more concerning features, the clinician needs to consider their urgency. Is it a medical emergency (eg cauda equina) which requires immediate action or potential metastases, which could wait a few days, but still requires urgent referral?[7]

Pathway[edit | edit source]

The pathway helps clinicians understand what they should do with patients who present with concerning features. This pathway is moveable and flexible - a patient can move between pathways.[7]

Summary[edit | edit source]

- It is important to consider serious pathology as a differential diagnosis. Clinicians need to consider how a red flag presents for a particular patient. Context is essential.

- Red flags should be re-evaluated at every session.

- It is important to identify which pathway a patient should be on, to ensure that they receive the correct care in a timely fashion.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Finucane L. An Introduction to Red Flags in Serious Pathology. Physioplus 2020.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Premkumar A, Godfrey W, Gottschalk MB, Boden SD. Red Flags for Low Back Pain Are Not Always Really Red. J Bone Jt Surg. 2018;100(5):368–74.

- ↑ Cook CE, George S Z, Reiman M P. Red flag screening for low back pain: nothing to see here, move along: a narrative review. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2018;52: 493–496.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Yusuf M, Finucane L, Selfe J. Red flags for the early detection of spinal infection in low back pain. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2019; 20(606). Available at: https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12891-019-2949-6

- ↑ Verhagen AP, Downie A, Maher CG, Koes BW. Most red flags for malignancy in low back pain guidelines lack empirical support: a systematic review. Pain. 2017;158(10):1860-8.

- ↑ Verhagen AP, Downie A, Popal N, Maher CG, Koes BW. Red flags pre

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Finucane L, Selfe J, Mercer C, Greenhalgh S, Downie A, Pool A et al. An evidence informed clinical reasoning framework for clinicians in the face of serious pathology in the spine course slide. Physioplus 2020.