Adolescent Back Pain: Difference between revisions

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

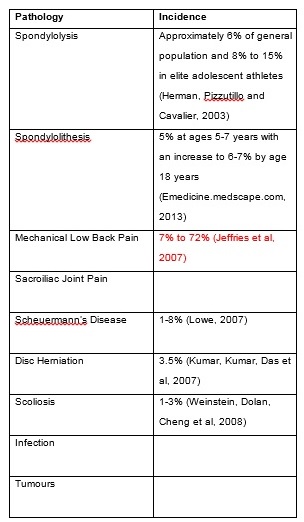

'''<u>Introduction</u>'''<br> | '''<u>Introduction</u>'''<br> <u></u> The World Health Organization describes adolescence as “young people between the ages of 10 and 19 years”<ref name="WHO">Who.int. WHO | Adolescent health [Internet]. 2015 [cited 9 January 2015]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/adolescent_health/en/</ref>. This definition is further divided into early adolescence (10-14 years old) to late adolescence (15-19 years old) by the United Nations Population Fund <ref name="United Nations">Unfpa.org. UNFPA - United Nations Population Fund | State of World Population 2003 [Internet]. 2003 [cited 12 January 2015]. Available from: http://www.unfpa.org/publications/state-world-population-2003</ref>. Adolescent back pain has been reported to be as common as that of adult populations <ref name="Jones and Macfarlane">Jones G, Macfarlane G. Epidemiology of low back pain in children and adolescents. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2005;90(3):312-316.</ref><ref name="Burton et al">Burton A, Clarke R, McClune T, Tillotson K. The Natural History of Low Back Pain in Adolescents. Spine. 1996;21(20):2323-2328.</ref><ref name="Harreby et al">Harreby M, Neergaard K, Hesselsôe G, Kjer J. Are Radiologic Changes in the Thoracic and Lumbar Spine of Adolescents Risk Factors for Low Back Pain in Adults?. Spine. 1995;20(21):2298-2302.</ref> and has been attributed to a number of factors such as gender <ref name="Grimmer, Nyland, Milanese">Grimmer K, Nyland L, Milanese S. Longitudinal investigation of low back pain in Australian adolescents: a five-year study. Physiother Res Int. 2006;11(3):161-172.</ref>, age <ref name="Jeffries et al">Jeffries L, Milanese S, Grimmer-Somers K. Epidemiology of Adolescent Spinal Pain. Spine. 2007;32(23):2630-2637.</ref>, sitting for long periods <ref name="Grimmer and Williams">Grimmer K, Williams M. Gender-age environmental associates of adolescent low back pain. Applied Ergonomics. 2000;31(4):343-360.</ref>, working at computers <ref name="Hakala et al">Hakala P, Rimpela A, Saarni L, Salminen J. Frequent computer-related activities increase the risk of neck-shoulder and low back pain in adolescents. The European Journal of Public Health. 2005;16(5):536-541.</ref>, school seating <ref name="Troussiere et al">Troussiere B, Tesniere C, Fauconnier J, Grison J, Juvin R, Phelip X. Comparative study of two different kinds of school furniture among children. Ergonomics. 1999;42(3):516-526.</ref> and psychological factors <ref name="Astfalck et al">Astfalck R, O'Sullivan P, Straker L, Smith A. A detailed characterisation of pain, disability, physical and psychological features of a small group of adolescents with non-specific chronic low back pain. Manual Therapy. 2010;15(3):240-247.</ref>. <br> '''<u>Epidemiology</u>''' <u></u> <span style="line-height: 1.5em;">There has been a high prevalence of low back pain (LBP) in adolescents demonstrated in a number of epidemiological studies </span><ref name="Pellise et al">Pellisé F, Balagué F, Rajmil L, Cedraschi C, Aguirre M, Fontecha C et al. Prevalence of Low Back Pain and Its Effect on Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(1):65.</ref><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">. Estimates of the prevalence of back pain in children adolescents vary greatly, ranging from 30%-70% </span><ref name="Balague et al">Balagué F, Troussier B, Salminen J. Non-specific low back pain in children and adolescents: risk factors. European Spine Journal. 1999;8(6):429-438.</ref><ref name="Wedderkopp et al">Wedderkopp N, Leboeuf-Yde C, Andersen L, Froberg K, Hansen H. Back Pain Reporting Pattern in a Danish Population-Based Sample of Children and Adolescents. Spine. 2001;26(17):1879-1883.</ref><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">. The study by Jeffries et al (2007) found a life time prevalence ranging from 4.7% to 74.4% for spinal or back pain and 7% to 72% for LBP</span><ref name="Jeffries et al" /><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">. These ranges depend on the age of the participants and the methodological differences, in particular the definition of back pain used</span><ref name="Jones and Macfarlane" /><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">. </span> <span style="line-height: 1.5em;" /><br>This level of prevalence raises concerns due to the link between LBP in adolescents and chronic LBP in adulthood<ref name="Hestbaek et al">Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik K, Manniche C. The Course of Low Back Pain From Adolescence to Adulthood. Spine. 2006;31(4):468-472.</ref>. A history of symptoms has been found to be the strongest predictor of future LBP<ref name="Papageorgiou et al">Papageorgiou A, Croft P, Thomas E, Ferry S, Jayson M, Silman A. Influence of previous pain experience on the episode incidence of low back pain: results from the South Manchester Back Pain Study. Pain. 1996;66(2-3):181-185.</ref> and an early onset in life linked to chronicity<ref name="Brattberg">Brattberg G. The incidence of back pain and headache among Swedish school children. Qual Life Res. 1994;3(S1):S27-S31.</ref><ref name="Harreby et al" />. It has been found that the occurrence of back pain in adolescents increases with age, in particular in the years of early teens<ref name="Jeffries et al" />. <br>Growth and development of males and females is remarkably similar up to approximately the age of 10<ref name="Brundtland et al">Brundtland G, Liestol K, Walloe L. Height and weight of school children and adolescent girls and boys in Oslo 1970. Acta Paediatrica. 1975;64(4):565-573.</ref>. Above the age of 10, as a result of puberty, the growth patterns of males and females deviate considerably<ref name="Brundtland et al" />. By at least the age of 18 or 19 years, puberty is considered to have ceased<ref name="Jeffries et al" />. With the potential influence of puberty related growth on the incidence of adolescent back pain <ref name="Feldman">Feldman D. Risk Factors for the Development of Low Back Pain in Adolescence. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;154(1):30-36.</ref> it is imperative that the range of pubertal ages are taken into consideration in epidemiological studies<ref name="Jeffries et al" />. <br> '''<u>Aetiology</u>''' [[Image:Aetiology table.jpg]] <br> MUSCULOSKELETAL (MSK)<br>Adolescent back pain predominantly falls into 3 general categories: muscular, bone-related, and discogenic (http://drjordanmetzl.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/BackPain-in-the-Adolescent.pdf). Each with characteristic features as displayed in this section: Muscle-related pain <br>Most back pain in adolescents, as in adults, is thought to arise from within the muscles (Kim and Green, 2008). Muscle-related pain tends to be localised to paraspinal muscles of the thoracic or lumbar area rather than to the spine itself (http://drjordanmetzl.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/BackPain-in-the-Adolescent.pdf). This pain is most commonly related to overuse, but there may be a history of acute injury. <br>The contributing factors may include:<br>- Carrying a heavy rucksack (Macias et al., 2008)(Rodríguez-Oviedo et al., 2012)<br>- Incorrect sports equipment (e.g. improper bicycle seat positioning, lack of cushioned insoles for running) (Baker and Patel, 2005)<br>- Psychosocial distress, depression and anxiety (Combs and Caskey, 1997)(Diepenmaat et al., 2006)<br>Bone-related pain <br>Bone-related pain tends to occur at the centre of the spine and usually exacerbated by extension (backward bending) (http://drjordanmetzl.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/BackPain-in-the-Adolescent.pdf), though this finding is not specific.<br>Common causes of bone related back pain amongst adolescents: <br>Spondylolysis and Isthmic Spondylolisthesis<br>Spondylolysis - is a unilateral/bilateral defect (separation) in the vertebral pars interarticularis (usually the lower lumbar vertebrae - particularly L5) (Morita et al., 1995).<br>Spondylolysis usually presents in early adolescence. It may be asymptomatic initially, but typically manifests as aching low back pain exacerbated by hyperextension of the spine and relieved by rest (Kim and Green, 2008). Spondylolysis is common in adolescent athletes with acute low back pain - accounting for 47% of cases in one orthopaedic series (Micheli and Wood, 1995). The risk of developing Spondylolysis tends to correlate in athletes whose sport requires repetitive flexion/extension or hyperextension (Baker and Patel, 2005)<br>Spondylolisthesis - occurs when bilateral defects permit the vertebral body to slip anteriorly - the most common spondylolytic defects occur at the isthmus (Ginsburg and Bassett, 1997). Spondylolysis progresses to spondylolisthesis in approximately 15 % of cases (Fredrickson et al., 1984). Progression generally occurs during the teenage growth spurt, with minimal change after 16 years of age (Lonstein, 1999)(Motley et al., 1998). Morita et al (1995) suggests progression to spondylolisthesis is correlated with persistent pain…ADD SOMETHING ON!!!<br>Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis<br>Scoliosis — Scoliosis is an abnormal lateral curvature of the spine. It can be idiopathic or result from congenital spinal anomalies, muscular spasm or paralysis, infection, tumour, or other causes (REFERENCE)<br>Idiopathic scoliosis is scoliosis for which there is no definite aetiology. <br>Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is the most common form of idiopathic scoliosis, accounting for 80 to 85% of cases (Negrini et al., 2012). AIS is also noted as the most common spinal deformity seen by primary care physicians, paediatricians, and spinal surgeons (Altaf et al., 2013).The prevalence of AIS with a Cobb angle ≥10º is approximately 3 %. However, only 10% of adolescents with AIS require treatment. Males and females are affected equally. Though, the risk of curve progression and therefore the need for later treatment is 10 x higher in females (Miller, 1999).<br>Scheuermann’s Disease / Juvenile Kyphosis<br>Scheuermann’s Disease — is the abnormal growth (osteochondrosis), typically of the thoracolumbar spine leading to increasing spinal curvature (Cassas and Cassettari-Wayhs, 2006) It may be associated with spondylosis (Ogilvie and Sherman, 1987), Scheuermann’s is the most common cause of structural kyphosis in adolescents (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17556132?dopt=Abstract) and often accompanied with poor posture and backache (http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/311959-overview)<br>Disc-related pain<br>Disc-related pain is generally exacerbated by flexion (forward bending) and may radiate (http://drjordanmetzl.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/BackPain-in-the-Adolescent.pdf). Approximately 10% of persistent back pain in adolescents is disc related (http://archpedi.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=517423).<br>Disc herniation — vertebral bodies are separated by intervertebral discs, (to provide support and mobility). The intervertebral disc is composed of a tough, ligamentous outer annulus and a gelatinous inner nucleus pulposus. The combination of intervertebral pressure and degeneration of the ligamentous fibres can lead to a tear in the annulus, allowing herniation of the nucleus pulposus. <br>Disc herniation is a common disorder among adults with degenerated intervertebral discs. However, its occurrence in adolescence is much less frequent mostly as adolescents tend to have a healthier lumbar spine (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2899810/ ). Herniation of the nucleus pulposus is much less common in children and adolescents than in adults (REFERENCE = Lumbar disc herniation in young children R Haidar1 et al 2009) http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/priority_medicines/Ch6_24LBP.pdf <br>Risk factors for disc herniation include: (DePalma and Bhargava, 2006) <br>- Acute trauma (reference)<br>- Scheuermann’s disease (reference)<br>- Family history of disc herniation(http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=1824705) <br>- Obesity (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=21471420) <br>- Sporting activities e.g. weight lifting, wrestling, gymnastics, and collision sports<br> <br>TUMOURS<br>Osteoid Osteoma — Back pain caused by a spinal tumour is a rare occurrence (http://www.spine-health.com/conditions/lower-back-pain/potential-causes-back-pain-children-and-teens). The most common tumour that presents with back pain in adolescents is osteoid osteoma (REFERENCE), a benign tumour characterized by nocturnal pain and prompt relief with NSAIDs, although these features are variable. Only 10 to 20% of osteoid osteomas are localised to the spine (Cohen et al., 1983)<br><br> <br> '''<u>Treatment</u>''' <u></u> Treatment of LBP in adults has been investigated extensively (Calvo). Evidence has shown that physiotherapy treatment with exercise, back school and manual therapy are effective in reducing pain and functional limitations in adults (Heymans et al and Aure). A study looking at low back pain in adolescent athletes suggested that despite undergoing pubescent changes into adulthood, adolescents cannot be treated like young adults. Therefore, treatment of adolescents can be difficult and must be approached differently, with good understanding of spinal development (De Luigi). <br> Investigation and practice of therapeutic treatments for children and adolescents with back pain is more recent than with adults (Calvo-Muñoz). Treatments used include back education, exercise, manual therapy and therapeutic conditioning. These interventions are primarily aimed at decreasing the prevalence, and lessening the intensity of LBP and disability (Calvo-Muñoz). <br> Preventative treatments have been carried out over the last 3 decades, including physical therapy exercises, postural hygiene and the promotion of physical activity (Calvo-Muñoz). According to Curtis and d’Hemecourt (2007) the best prevention of back pain is early detection. Preventative measures can include ‘proper technique’ e.g. in lifting sports and limiting excessive lumbar lordosis, plus participating in core-strengthening exercises and stretches for tight hamstrings and hip flexors which also may help reduce the risk of low back pain (Purcell). <br> Some literature suggests that back packs carried by schoolchildren can cause back pain if they are to heavy or if the weight is carried unevenly. (?NHSCHOICES) According to this group-randomised control trial the following should be advised to prevent LBP: *Load the minimum weight possible *Carry a school backpack on two shoulders *Correct the belief that school backpack weight does not affect the back *Using a locker at school (Vidal, 2013)<br><br>The study found that children were able to learn healthy backpack habits. However, this study was in primary school aged children rather than secondary, therefore results may not be generalisable for an adolescent population. <br> <br>It has been concluded that physiotherapy treatments seem to be effective in adolescents with LBP (Calvo-Muñoz). <br>Suggested treatments for the rehabilitation of adolescents with back pain include:<br> #'''Back education''' (theoretical or practical)- acquisition of knowledge, posture training habits, body awareness training<br> #'''Exercise'''- including stretching, strengthening, breathing, posture correction, balance exercises, functional exercises, warm-up, relaxation, coordination, stabilisation.<br><br>

A study which evaluated the efficacy of an exercise program for recurrent non-specific back pain in adolescents, concluding that an exercise was an effective short-term treatment strategy, incorporated the following forms of exercise:

<br><br>a) '''Pain relieving exercises''' which encourage motion of the lumbar spine to reduce joint stiffness such as the ‘cat stretch’ and flexibility exercises for the hip and knee, such as knees to chest and knees to the side<br><br>

b)'''Reconditioning exercises''' aiming to provide muscle endurance of lumbar stabilisers and help encourage appropriate motor control of muscle recruitment such as ‘superman’ single leg extension holds in ?4 point kneeling.<br><br>

c) '''Progressive exercises''' imposing a higher challenge on the lumbar stabilisers and more strength related activities, for instance horizontal side support on feet.

<br> #'''Manual therapy'''- mobilisation, manipulation, massage<br> #'''Therapeutic physical conditioning'''- walking, running, swimming, cycling. (Calvo-Muñoz).<br> <br> A meta analysis in 2013 examined the differential effectiveness of physiotherapy treatment for LBP in children and adolescents aiming to determine whether the treatments were beneficial for pain and disability among other outcome variables. Prior to this analysis, there was no solid evidence to suggest which treatment was most effective for adolescents with back pain.<br> All the treatment outcome measures reached a statistically significant effect magnitude and showed a clinically relevant improvement of symptoms. The most effective combination treatment was therapeutic physical conditioning (ie general fitness) and manual therapy. However, there was limited details of what the treatments actually involved.<br> <br> <u>Intensity and duration of treatment</u> The study found that the average: *number of weeks of treatment was 12 *time a week spent engaging in treatment was 1 hour <br><u>Quality of the study</u><br>The meta-analysis itself has good methodological quality, however, there was a low number of applicable studies with only 8 articles met the selection criteria. There was also a lack of control groups and methodological quality of the studies was poor. This prevents definite conclusions being drawn. Furthermore, no evidence was provided regarding the duration of the beneficial effects, or details of follow up. <br>According to Jones et al, 2007 and Cardon et al 2007, there is a need to incorporate back care and exercise into physical education curricula in schools.<br> Interestingly, an RCT by Ahlqwist (2008) found that an active physiotherapy program improved adolescent experience of back pain regardless of whether the program consisted of supervised exercises by a physiotherapist.<br> <u></u> <u>Conclusion</u> <br> Outcome measures<br><br>There are many different outcome measures that may be used by physiotherapists in their treatment of adolescents with back pain. *Pain e.g. VAS, Painometer (a smartphone app to assess pain intensity) *Disability e.g. Modified Oswestry Disability Questionnaire, Roland & Morris Disability Questionnaire *Flexibility eg Back-saver sit and reach *Endurance *Mental health *Quality of life e.g. Child Health Questionnaire Child Form 87 *Function *Self efficacy *Return to sport *Return to study/work <br> <br> <br><u>Further research</u><br> <br> <u>References</u> <references /> <br> | ||

<u></u> | |||

The World Health Organization describes adolescence as “young people between the ages of 10 and 19 years”<ref>Who.int. WHO | Adolescent health [Internet]. 2015 [cited 9 January 2015]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/adolescent_health/en/</ref>. This definition is further divided into early adolescence (10-14 years old) to late adolescence (15-19 years old) by the United Nations Population Fund <ref>Unfpa.org. UNFPA - United Nations Population Fund | |||

<br> | |||

'''<u>Epidemiology</u>''' | |||

<u></u> | |||

<span style="line-height: 1.5em;">There has been a high prevalence of low back pain (LBP) in adolescents demonstrated in a number of epidemiological studies </span><ref>Pellisé F, Balagué F, Rajmil L, Cedraschi C, Aguirre M, Fontecha C et al. Prevalence of Low Back Pain and Its Effect on Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(1):65.</ref><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">. Estimates of the prevalence of back pain in children adolescents vary greatly, ranging from 30%-70% </span><ref | |||

<span style="line-height: 1.5em;" /><br>This level of prevalence raises concerns due to the link between LBP in adolescents and chronic LBP in adulthood<ref>Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik K, Manniche C. The Course of Low Back Pain From Adolescence to Adulthood. Spine. 2006;31(4):468-472.</ref>. A history of symptoms has been found to be the strongest predictor of future LBP<ref>Papageorgiou A, Croft P, Thomas E, Ferry S, Jayson M, Silman A. Influence of previous pain experience on the episode incidence of low back pain: results from the South Manchester Back Pain Study. Pain. 1996;66(2-3):181-185.</ref> and an early onset in life linked to chronicity<ref>Brattberg G. The incidence of back pain and headache among Swedish school children. Qual Life Res. 1994;3(S1):S27-S31.</ref> | |||

<br>Growth and development of males and females is remarkably similar up to approximately the age of 10<ref>Brundtland G, Liestol K, Walloe L. Height and weight of school children and adolescent girls and boys in Oslo 1970. Acta Paediatrica. 1975;64(4):565-573.</ref>. Above the age of 10, as a result of puberty, the growth patterns of males and females deviate considerably | |||

<br> | |||

'''<u>Aetiology</u>''' | |||

< | |||

Adolescent back pain predominantly falls into 3 general categories: muscular, bone-related, and discogenic | |||

Each with characteristic features as displayed in this section: | |||

Most back pain in adolescents, as in adults, is thought to arise from within the muscles | |||

<br>The contributing factors may include:<br>- Carrying a heavy rucksack | |||

<br> | |||

< | |||

< | |||

<br> | |||

* | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

< | |||

Revision as of 12:04, 14 January 2015

Introduction

The World Health Organization describes adolescence as “young people between the ages of 10 and 19 years”[1]. This definition is further divided into early adolescence (10-14 years old) to late adolescence (15-19 years old) by the United Nations Population Fund [2]. Adolescent back pain has been reported to be as common as that of adult populations [3][4][5] and has been attributed to a number of factors such as gender [6], age [7], sitting for long periods [8], working at computers [9], school seating [10] and psychological factors [11].

Epidemiology There has been a high prevalence of low back pain (LBP) in adolescents demonstrated in a number of epidemiological studies [12]. Estimates of the prevalence of back pain in children adolescents vary greatly, ranging from 30%-70% [13][14]. The study by Jeffries et al (2007) found a life time prevalence ranging from 4.7% to 74.4% for spinal or back pain and 7% to 72% for LBP[7]. These ranges depend on the age of the participants and the methodological differences, in particular the definition of back pain used[3]. <span style="line-height: 1.5em;" />

This level of prevalence raises concerns due to the link between LBP in adolescents and chronic LBP in adulthood[15]. A history of symptoms has been found to be the strongest predictor of future LBP[16] and an early onset in life linked to chronicity[17][5]. It has been found that the occurrence of back pain in adolescents increases with age, in particular in the years of early teens[7].

Growth and development of males and females is remarkably similar up to approximately the age of 10[18]. Above the age of 10, as a result of puberty, the growth patterns of males and females deviate considerably[18]. By at least the age of 18 or 19 years, puberty is considered to have ceased[7]. With the potential influence of puberty related growth on the incidence of adolescent back pain [19] it is imperative that the range of pubertal ages are taken into consideration in epidemiological studies[7].

Aetiology

MUSCULOSKELETAL (MSK)

Adolescent back pain predominantly falls into 3 general categories: muscular, bone-related, and discogenic (http://drjordanmetzl.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/BackPain-in-the-Adolescent.pdf). Each with characteristic features as displayed in this section: Muscle-related pain

Most back pain in adolescents, as in adults, is thought to arise from within the muscles (Kim and Green, 2008). Muscle-related pain tends to be localised to paraspinal muscles of the thoracic or lumbar area rather than to the spine itself (http://drjordanmetzl.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/BackPain-in-the-Adolescent.pdf). This pain is most commonly related to overuse, but there may be a history of acute injury.

The contributing factors may include:

- Carrying a heavy rucksack (Macias et al., 2008)(Rodríguez-Oviedo et al., 2012)

- Incorrect sports equipment (e.g. improper bicycle seat positioning, lack of cushioned insoles for running) (Baker and Patel, 2005)

- Psychosocial distress, depression and anxiety (Combs and Caskey, 1997)(Diepenmaat et al., 2006)

Bone-related pain

Bone-related pain tends to occur at the centre of the spine and usually exacerbated by extension (backward bending) (http://drjordanmetzl.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/BackPain-in-the-Adolescent.pdf), though this finding is not specific.

Common causes of bone related back pain amongst adolescents:

Spondylolysis and Isthmic Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolysis - is a unilateral/bilateral defect (separation) in the vertebral pars interarticularis (usually the lower lumbar vertebrae - particularly L5) (Morita et al., 1995).

Spondylolysis usually presents in early adolescence. It may be asymptomatic initially, but typically manifests as aching low back pain exacerbated by hyperextension of the spine and relieved by rest (Kim and Green, 2008). Spondylolysis is common in adolescent athletes with acute low back pain - accounting for 47% of cases in one orthopaedic series (Micheli and Wood, 1995). The risk of developing Spondylolysis tends to correlate in athletes whose sport requires repetitive flexion/extension or hyperextension (Baker and Patel, 2005)

Spondylolisthesis - occurs when bilateral defects permit the vertebral body to slip anteriorly - the most common spondylolytic defects occur at the isthmus (Ginsburg and Bassett, 1997). Spondylolysis progresses to spondylolisthesis in approximately 15 % of cases (Fredrickson et al., 1984). Progression generally occurs during the teenage growth spurt, with minimal change after 16 years of age (Lonstein, 1999)(Motley et al., 1998). Morita et al (1995) suggests progression to spondylolisthesis is correlated with persistent pain…ADD SOMETHING ON!!!

Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis

Scoliosis — Scoliosis is an abnormal lateral curvature of the spine. It can be idiopathic or result from congenital spinal anomalies, muscular spasm or paralysis, infection, tumour, or other causes (REFERENCE)

Idiopathic scoliosis is scoliosis for which there is no definite aetiology.

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is the most common form of idiopathic scoliosis, accounting for 80 to 85% of cases (Negrini et al., 2012). AIS is also noted as the most common spinal deformity seen by primary care physicians, paediatricians, and spinal surgeons (Altaf et al., 2013).The prevalence of AIS with a Cobb angle ≥10º is approximately 3 %. However, only 10% of adolescents with AIS require treatment. Males and females are affected equally. Though, the risk of curve progression and therefore the need for later treatment is 10 x higher in females (Miller, 1999).

Scheuermann’s Disease / Juvenile Kyphosis

Scheuermann’s Disease — is the abnormal growth (osteochondrosis), typically of the thoracolumbar spine leading to increasing spinal curvature (Cassas and Cassettari-Wayhs, 2006) It may be associated with spondylosis (Ogilvie and Sherman, 1987), Scheuermann’s is the most common cause of structural kyphosis in adolescents (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17556132?dopt=Abstract) and often accompanied with poor posture and backache (http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/311959-overview)

Disc-related pain

Disc-related pain is generally exacerbated by flexion (forward bending) and may radiate (http://drjordanmetzl.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/BackPain-in-the-Adolescent.pdf). Approximately 10% of persistent back pain in adolescents is disc related (http://archpedi.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=517423).

Disc herniation — vertebral bodies are separated by intervertebral discs, (to provide support and mobility). The intervertebral disc is composed of a tough, ligamentous outer annulus and a gelatinous inner nucleus pulposus. The combination of intervertebral pressure and degeneration of the ligamentous fibres can lead to a tear in the annulus, allowing herniation of the nucleus pulposus.

Disc herniation is a common disorder among adults with degenerated intervertebral discs. However, its occurrence in adolescence is much less frequent mostly as adolescents tend to have a healthier lumbar spine (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2899810/ ). Herniation of the nucleus pulposus is much less common in children and adolescents than in adults (REFERENCE = Lumbar disc herniation in young children R Haidar1 et al 2009) http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/priority_medicines/Ch6_24LBP.pdf

Risk factors for disc herniation include: (DePalma and Bhargava, 2006)

- Acute trauma (reference)

- Scheuermann’s disease (reference)

- Family history of disc herniation(http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=1824705)

- Obesity (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=21471420)

- Sporting activities e.g. weight lifting, wrestling, gymnastics, and collision sports

TUMOURS

Osteoid Osteoma — Back pain caused by a spinal tumour is a rare occurrence (http://www.spine-health.com/conditions/lower-back-pain/potential-causes-back-pain-children-and-teens). The most common tumour that presents with back pain in adolescents is osteoid osteoma (REFERENCE), a benign tumour characterized by nocturnal pain and prompt relief with NSAIDs, although these features are variable. Only 10 to 20% of osteoid osteomas are localised to the spine (Cohen et al., 1983)

Treatment Treatment of LBP in adults has been investigated extensively (Calvo). Evidence has shown that physiotherapy treatment with exercise, back school and manual therapy are effective in reducing pain and functional limitations in adults (Heymans et al and Aure). A study looking at low back pain in adolescent athletes suggested that despite undergoing pubescent changes into adulthood, adolescents cannot be treated like young adults. Therefore, treatment of adolescents can be difficult and must be approached differently, with good understanding of spinal development (De Luigi).

Investigation and practice of therapeutic treatments for children and adolescents with back pain is more recent than with adults (Calvo-Muñoz). Treatments used include back education, exercise, manual therapy and therapeutic conditioning. These interventions are primarily aimed at decreasing the prevalence, and lessening the intensity of LBP and disability (Calvo-Muñoz).

Preventative treatments have been carried out over the last 3 decades, including physical therapy exercises, postural hygiene and the promotion of physical activity (Calvo-Muñoz). According to Curtis and d’Hemecourt (2007) the best prevention of back pain is early detection. Preventative measures can include ‘proper technique’ e.g. in lifting sports and limiting excessive lumbar lordosis, plus participating in core-strengthening exercises and stretches for tight hamstrings and hip flexors which also may help reduce the risk of low back pain (Purcell).

Some literature suggests that back packs carried by schoolchildren can cause back pain if they are to heavy or if the weight is carried unevenly. (?NHSCHOICES) According to this group-randomised control trial the following should be advised to prevent LBP: *Load the minimum weight possible *Carry a school backpack on two shoulders *Correct the belief that school backpack weight does not affect the back *Using a locker at school (Vidal, 2013)

The study found that children were able to learn healthy backpack habits. However, this study was in primary school aged children rather than secondary, therefore results may not be generalisable for an adolescent population.

It has been concluded that physiotherapy treatments seem to be effective in adolescents with LBP (Calvo-Muñoz).

Suggested treatments for the rehabilitation of adolescents with back pain include:

#Back education (theoretical or practical)- acquisition of knowledge, posture training habits, body awareness training

#Exercise- including stretching, strengthening, breathing, posture correction, balance exercises, functional exercises, warm-up, relaxation, coordination, stabilisation.

A study which evaluated the efficacy of an exercise program for recurrent non-specific back pain in adolescents, concluding that an exercise was an effective short-term treatment strategy, incorporated the following forms of exercise:

a) Pain relieving exercises which encourage motion of the lumbar spine to reduce joint stiffness such as the ‘cat stretch’ and flexibility exercises for the hip and knee, such as knees to chest and knees to the side

b)Reconditioning exercises aiming to provide muscle endurance of lumbar stabilisers and help encourage appropriate motor control of muscle recruitment such as ‘superman’ single leg extension holds in ?4 point kneeling.

c) Progressive exercises imposing a higher challenge on the lumbar stabilisers and more strength related activities, for instance horizontal side support on feet.

#Manual therapy- mobilisation, manipulation, massage

#Therapeutic physical conditioning- walking, running, swimming, cycling. (Calvo-Muñoz).

A meta analysis in 2013 examined the differential effectiveness of physiotherapy treatment for LBP in children and adolescents aiming to determine whether the treatments were beneficial for pain and disability among other outcome variables. Prior to this analysis, there was no solid evidence to suggest which treatment was most effective for adolescents with back pain.

All the treatment outcome measures reached a statistically significant effect magnitude and showed a clinically relevant improvement of symptoms. The most effective combination treatment was therapeutic physical conditioning (ie general fitness) and manual therapy. However, there was limited details of what the treatments actually involved.

Intensity and duration of treatment The study found that the average: *number of weeks of treatment was 12 *time a week spent engaging in treatment was 1 hour

Quality of the study

The meta-analysis itself has good methodological quality, however, there was a low number of applicable studies with only 8 articles met the selection criteria. There was also a lack of control groups and methodological quality of the studies was poor. This prevents definite conclusions being drawn. Furthermore, no evidence was provided regarding the duration of the beneficial effects, or details of follow up.

According to Jones et al, 2007 and Cardon et al 2007, there is a need to incorporate back care and exercise into physical education curricula in schools.

Interestingly, an RCT by Ahlqwist (2008) found that an active physiotherapy program improved adolescent experience of back pain regardless of whether the program consisted of supervised exercises by a physiotherapist.

Conclusion

Outcome measures

There are many different outcome measures that may be used by physiotherapists in their treatment of adolescents with back pain. *Pain e.g. VAS, Painometer (a smartphone app to assess pain intensity) *Disability e.g. Modified Oswestry Disability Questionnaire, Roland & Morris Disability Questionnaire *Flexibility eg Back-saver sit and reach *Endurance *Mental health *Quality of life e.g. Child Health Questionnaire Child Form 87 *Function *Self efficacy *Return to sport *Return to study/work

Further research

References

- ↑ Who.int. WHO | Adolescent health [Internet]. 2015 [cited 9 January 2015]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/adolescent_health/en/

- ↑ Unfpa.org. UNFPA - United Nations Population Fund | State of World Population 2003 [Internet]. 2003 [cited 12 January 2015]. Available from: http://www.unfpa.org/publications/state-world-population-2003

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Jones G, Macfarlane G. Epidemiology of low back pain in children and adolescents. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2005;90(3):312-316.

- ↑ Burton A, Clarke R, McClune T, Tillotson K. The Natural History of Low Back Pain in Adolescents. Spine. 1996;21(20):2323-2328.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Harreby M, Neergaard K, Hesselsôe G, Kjer J. Are Radiologic Changes in the Thoracic and Lumbar Spine of Adolescents Risk Factors for Low Back Pain in Adults?. Spine. 1995;20(21):2298-2302.

- ↑ Grimmer K, Nyland L, Milanese S. Longitudinal investigation of low back pain in Australian adolescents: a five-year study. Physiother Res Int. 2006;11(3):161-172.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Jeffries L, Milanese S, Grimmer-Somers K. Epidemiology of Adolescent Spinal Pain. Spine. 2007;32(23):2630-2637.

- ↑ Grimmer K, Williams M. Gender-age environmental associates of adolescent low back pain. Applied Ergonomics. 2000;31(4):343-360.

- ↑ Hakala P, Rimpela A, Saarni L, Salminen J. Frequent computer-related activities increase the risk of neck-shoulder and low back pain in adolescents. The European Journal of Public Health. 2005;16(5):536-541.

- ↑ Troussiere B, Tesniere C, Fauconnier J, Grison J, Juvin R, Phelip X. Comparative study of two different kinds of school furniture among children. Ergonomics. 1999;42(3):516-526.

- ↑ Astfalck R, O'Sullivan P, Straker L, Smith A. A detailed characterisation of pain, disability, physical and psychological features of a small group of adolescents with non-specific chronic low back pain. Manual Therapy. 2010;15(3):240-247.

- ↑ Pellisé F, Balagué F, Rajmil L, Cedraschi C, Aguirre M, Fontecha C et al. Prevalence of Low Back Pain and Its Effect on Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(1):65.

- ↑ Balagué F, Troussier B, Salminen J. Non-specific low back pain in children and adolescents: risk factors. European Spine Journal. 1999;8(6):429-438.

- ↑ Wedderkopp N, Leboeuf-Yde C, Andersen L, Froberg K, Hansen H. Back Pain Reporting Pattern in a Danish Population-Based Sample of Children and Adolescents. Spine. 2001;26(17):1879-1883.

- ↑ Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik K, Manniche C. The Course of Low Back Pain From Adolescence to Adulthood. Spine. 2006;31(4):468-472.

- ↑ Papageorgiou A, Croft P, Thomas E, Ferry S, Jayson M, Silman A. Influence of previous pain experience on the episode incidence of low back pain: results from the South Manchester Back Pain Study. Pain. 1996;66(2-3):181-185.

- ↑ Brattberg G. The incidence of back pain and headache among Swedish school children. Qual Life Res. 1994;3(S1):S27-S31.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Brundtland G, Liestol K, Walloe L. Height and weight of school children and adolescent girls and boys in Oslo 1970. Acta Paediatrica. 1975;64(4):565-573.

- ↑ Feldman D. Risk Factors for the Development of Low Back Pain in Adolescence. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;154(1):30-36.