Adolescent Back Pain: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

Introduction<br> | '''<u>Introduction</u>'''<br> | ||

<u></u> | |||

The World Health Organization describes adolescence as “young people between the ages of 10 and 19 years”<ref name="WHO">Who.int. WHO | Adolescent health [Internet]. 2015 [cited 9 January 2015]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/adolescent_health/en/</ref>. This definition is further divided into early adolescence (10-14 years old) to late adolescence (15-19 years old) by the United Nations Population Fund <ref name="United Nations">Unfpa.org. UNFPA - United Nations Population Fund | State of World Population 2003 [Internet]. 2003 [cited 12 January 2015]. Available from: http://www.unfpa.org/publications/state-world-population-2003</ref>. Adolescent back pain has been reported to be as common as that of adult populations <ref name="Jones and Macfarlane">Jones G, Macfarlane G. Epidemiology of low back pain in children and adolescents. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2005;90(3):312-316.</ref><ref name="Burton et al">Burton A, Clarke R, McClune T, Tillotson K. The Natural History of Low Back Pain in Adolescents. Spine. 1996;21(20):2323-2328.</ref><ref name="Harreby et al">Harreby M, Neergaard K, Hesselsôe G, Kjer J. Are Radiologic Changes in the Thoracic and Lumbar Spine of Adolescents Risk Factors for Low Back Pain in Adults?. Spine. 1995;20(21):2298-2302.</ref> and has been attributed to a number of factors such as gender <ref name="Grimmer, Nyland, Milanese">Grimmer K, Nyland L, Milanese S. Longitudinal investigation of low back pain in Australian adolescents: a five-year study. Physiother Res Int. 2006;11(3):161-172.</ref>, age <ref name="Jeffries et al">Jeffries L, Milanese S, Grimmer-Somers K. Epidemiology of Adolescent Spinal Pain. Spine. 2007;32(23):2630-2637.</ref>, sitting for long periods <ref name="Grimmer and Williams">Grimmer K, Williams M. Gender-age environmental associates of adolescent low back pain. Applied Ergonomics. 2000;31(4):343-360.</ref>, working at computers <ref name="Hakala et al">Hakala P, Rimpela A, Saarni L, Salminen J. Frequent computer-related activities increase the risk of neck-shoulder and low back pain in adolescents. The European Journal of Public Health. 2005;16(5):536-541.</ref>, school seating <ref name="Troussiere et al">Troussiere B, Tesniere C, Fauconnier J, Grison J, Juvin R, Phelip X. Comparative study of two different kinds of school furniture among children. Ergonomics. 1999;42(3):516-526.</ref> and psychological factors <ref name="Astfalck et al">Astfalck R, O'Sullivan P, Straker L, Smith A. A detailed characterisation of pain, disability, physical and psychological features of a small group of adolescents with non-specific chronic low back pain. Manual Therapy. 2010;15(3):240-247.</ref>. | The World Health Organization describes adolescence as “young people between the ages of 10 and 19 years”<ref name="WHO">Who.int. WHO | Adolescent health [Internet]. 2015 [cited 9 January 2015]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/adolescent_health/en/</ref>. This definition is further divided into early adolescence (10-14 years old) to late adolescence (15-19 years old) by the United Nations Population Fund <ref name="United Nations">Unfpa.org. UNFPA - United Nations Population Fund | State of World Population 2003 [Internet]. 2003 [cited 12 January 2015]. Available from: http://www.unfpa.org/publications/state-world-population-2003</ref>. Adolescent back pain has been reported to be as common as that of adult populations <ref name="Jones and Macfarlane">Jones G, Macfarlane G. Epidemiology of low back pain in children and adolescents. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2005;90(3):312-316.</ref><ref name="Burton et al">Burton A, Clarke R, McClune T, Tillotson K. The Natural History of Low Back Pain in Adolescents. Spine. 1996;21(20):2323-2328.</ref><ref name="Harreby et al">Harreby M, Neergaard K, Hesselsôe G, Kjer J. Are Radiologic Changes in the Thoracic and Lumbar Spine of Adolescents Risk Factors for Low Back Pain in Adults?. Spine. 1995;20(21):2298-2302.</ref> and has been attributed to a number of factors such as gender <ref name="Grimmer, Nyland, Milanese">Grimmer K, Nyland L, Milanese S. Longitudinal investigation of low back pain in Australian adolescents: a five-year study. Physiother Res Int. 2006;11(3):161-172.</ref>, age <ref name="Jeffries et al">Jeffries L, Milanese S, Grimmer-Somers K. Epidemiology of Adolescent Spinal Pain. Spine. 2007;32(23):2630-2637.</ref>, sitting for long periods <ref name="Grimmer and Williams">Grimmer K, Williams M. Gender-age environmental associates of adolescent low back pain. Applied Ergonomics. 2000;31(4):343-360.</ref>, working at computers <ref name="Hakala et al">Hakala P, Rimpela A, Saarni L, Salminen J. Frequent computer-related activities increase the risk of neck-shoulder and low back pain in adolescents. The European Journal of Public Health. 2005;16(5):536-541.</ref>, school seating <ref name="Troussiere et al">Troussiere B, Tesniere C, Fauconnier J, Grison J, Juvin R, Phelip X. Comparative study of two different kinds of school furniture among children. Ergonomics. 1999;42(3):516-526.</ref> and psychological factors <ref name="Astfalck et al">Astfalck R, O'Sullivan P, Straker L, Smith A. A detailed characterisation of pain, disability, physical and psychological features of a small group of adolescents with non-specific chronic low back pain. Manual Therapy. 2010;15(3):240-247.</ref>. | ||

| Line 5: | Line 7: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Epidemiology | '''<u>Epidemiology</u>''' | ||

<u></u> | |||

<span style="line-height: 1.5em;">There has been a high prevalence of low back pain (LBP) in adolescents demonstrated in a number of epidemiological studies </span><ref name="Pellise et al">Pellisé F, Balagué F, Rajmil L, Cedraschi C, Aguirre M, Fontecha C et al. Prevalence of Low Back Pain and Its Effect on Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics &amp;amp; Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(1):65.</ref><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">. Estimates of the prevalence of back pain in children adolescents vary greatly, ranging from 30%-70% </span><ref name="Balague et al">Balagué F, Troussier B, Salminen J. Non-specific low back pain in children and adolescents: risk factors. European Spine Journal. 1999;8(6):429-438.</ref><ref name="Wedderkopp et al">Wedderkopp N, Leboeuf-Yde C, Andersen L, Froberg K, Hansen H. Back Pain Reporting Pattern in a Danish Population-Based Sample of Children and Adolescents. Spine. 2001;26(17):1879-1883.</ref><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">. The study by Jeffries et al (2007) found a life time prevalence ranging from 4.7% to 74.4% for spinal or back pain and 7% to 72% for LBP</span><ref name="Jeffries et al" /><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">. These ranges depend on the age of the participants and the methodological differences, in particular the definition of back pain used</span><ref name="Jones and Macfarlane" /><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">. </span> | |||

<span style="line-height: 1.5em;" /><br>This level of prevalence raises concerns due to the link between LBP in adolescents and chronic LBP in adulthood<ref name="Hestbaek et al">Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik K, Manniche C. The Course of Low Back Pain From Adolescence to Adulthood. Spine. 2006;31(4):468-472.</ref>. A history of symptoms has been found to be the strongest predictor of future LBP<ref name="Papageorgiou et al">Papageorgiou A, Croft P, Thomas E, Ferry S, Jayson M, Silman A. Influence of previous pain experience on the episode incidence of low back pain: results from the South Manchester Back Pain Study. Pain. 1996;66(2-3):181-185.</ref> and an early onset in life linked to chronicity<ref name="Brattberg">Brattberg G. The incidence of back pain and headache among Swedish school children. Qual Life Res. 1994;3(S1):S27-S31.</ref><ref name="Harreby et al" />. It has been found that the occurrence of back pain in adolescents increases with age, in particular in the years of early teens<ref name="Jeffries et al" />. | |||

<br>Growth and development of males and females is remarkably similar up to approximately the age of 10<ref name="Brundtland et al">Brundtland G, Liestol K, Walloe L. Height and weight of school children and adolescent girls and boys in Oslo 1970. Acta Paediatrica. 1975;64(4):565-573.</ref>. Above the age of 10, as a result of puberty, the growth patterns of males and females deviate considerably<ref name="Brundtland et al" />. By at least the age of 18 or 19 years, puberty is considered to have ceased<ref name="Jeffries et al" />. With the potential influence of puberty related growth on the incidence of adolescent back pain <ref name="Feldman">Feldman D. Risk Factors for the Development of Low Back Pain in Adolescence. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;154(1):30-36.</ref> it is imperative that the range of pubertal ages are taken into consideration in epidemiological studies<ref name="Jeffries et al" />. | |||

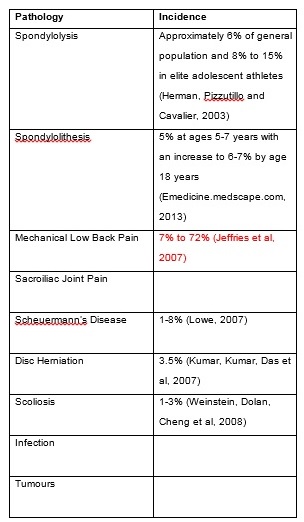

'''<u>Aetiology</u>''' | |||

[[Image:Aetiology table.jpg]] | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

'''<u>Treatment</u>''' | |||

<u></u> | |||

Treatment of LBP in adults has been investigated extensively (Calvo). Evidence has shown that physiotherapy treatment with exercise, back school and manual therapy are effective in reducing pain and functional limitations in adults (Heymans et al and Aure). A study looking at low back pain in adolescent athletes suggested that despite undergoing pubescent changes into adulthood, adolescents cannot be treated like young adults. Therefore, treatment of adolescents can be difficult and must be approached differently, with good understanding of spinal development (De Luigi). | |||

Investigation and practice of therapeutic treatments for children and adolescents with back pain is more recent than with adults (Calvo-Muñoz). Treatments used include back education, exercise, manual therapy and therapeutic conditioning. These interventions are primarily aimed at decreasing the prevalence, and lessening the intensity of LBP and disability (Calvo-Muñoz). | |||

Preventative treatments have been carried out over the last 3 decades, including physical therapy exercises, postural hygiene and the promotion of physical activity (Calvo-Muñoz). According to Curtis and d’Hemecourt (2007) the best prevention of back pain is early detection. Preventative measures can include ‘proper technique’ e.g. in lifting sports and limiting excessive lumbar lordosis, plus participating in core-strengthening exercises and stretches for tight hamstrings and hip flexors which also may help reduce the risk of low back pain (Purcell). | |||

Some literature suggests that back packs carried by schoolchildren can cause back pain if they are to heavy or if the weight is carried unevenly. (?NHSCHOICES) According to this group-randomised control trial the following should be advised to prevent LBP: | |||

*Load the minimum weight possible | |||

*Carry a school backpack on two shoulders | |||

*Correct the belief that school backpack weight does not affect the back | |||

*Using a locker at school | |||

(Vidal, 2013)<br><br>The study found that children were able to learn healthy backpack habits. However, this study was in primary school aged children rather than secondary, therefore results may not be generalisable for an adolescent population. <br> | |||

<br>It has been concluded that physiotherapy treatments seem to be effective in adolescents with LBP (Calvo-Muñoz). | |||

<br>Suggested treatments for the rehabilitation of adolescents with back pain include:<br> | |||

#'''Back education''' (theoretical or practical)- acquisition of knowledge, posture training habits, body awareness training<br> | |||

#'''Exercise'''- including stretching, strengthening, breathing, posture correction, balance exercises, functional exercises, warm-up, relaxation, coordination, stabilisation.<br><br>

A study which evaluated the efficacy of an exercise program for recurrent non-specific back pain in adolescents, concluding that an exercise was an effective short-term treatment strategy, incorporated the following forms of exercise:

<br>a) '''Pain relieving exercises''' which encourage motion of the lumbar spine to reduce joint stiffness such as the ‘cat stretch’ and flexibility exercises for the hip and knee, such as knees to chest and knees to the side<br><br>

b)'''Reconditioning exercises''' aiming to provide muscle endurance of lumbar stabilisers and help encourage appropriate motor control of muscle recruitment such as ‘superman’ single leg extension holds in ?4 point kneeling.<br><br>

c) '''Progressive exercises''' imposing a higher challenge on the lumbar stabilisers and more strength related activities, for instance horizontal side support on feet.

<br> | |||

'''Manual therapy'''- mobilisation, manipulation, massage<br> | |||

#'''Therapeutic physical conditioning'''- walking, running, swimming, cycling. | |||

(Calvo-Muñoz).<br> | |||

A meta analysis in 2013 examined the differential effectiveness of physiotherapy treatment for LBP in children and adolescents aiming to determine whether the treatments were beneficial for pain and disability among other outcome variables. Prior to this analysis, there was no solid evidence to suggest which treatment was most effective for adolescents with back pain.<br> | |||

All the treatment outcome measures reached a statistically significant effect magnitude and showed a clinically relevant improvement of symptoms. The most effective combination treatment was therapeutic physical conditioning (ie general fitness) and manual therapy. However, there was limited details of what the treatments actually involved.<br> | |||

<u>Intensity and duration of treatment</u> | |||

The study found that the average: | |||

*number of weeks of treatment was 12 | |||

*time a week spent engaging in treatment was 1 hour | |||

<br><u>Quality of the study</u><br>The meta-analysis itself has good methodological quality, however, there was a low number of applicable studies with only 8 articles met the selection criteria. There was also a lack of control groups and methodological quality of the studies was poor. This prevents definite conclusions being drawn. Furthermore, no evidence was provided regarding the duration of the beneficial effects, or details of follow up. | |||

<br>According to Jones et al, 2007 and Cardon et al 2007, there is a need to incorporate back care and exercise into physical education curricula in schools.<br> | |||

Interestingly, an RCT by Ahlqwist (2008) found that an active physiotherapy program improved adolescent experience of back pain regardless of whether the program consisted of supervised exercises by a physiotherapist.<br> | |||

<u>Conclusion</u> | |||

References | <u>References</u> | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

<br> <br><br> | <br> <br><br> | ||

Revision as of 23:22, 13 January 2015

Introduction

The World Health Organization describes adolescence as “young people between the ages of 10 and 19 years”[1]. This definition is further divided into early adolescence (10-14 years old) to late adolescence (15-19 years old) by the United Nations Population Fund [2]. Adolescent back pain has been reported to be as common as that of adult populations [3][4][5] and has been attributed to a number of factors such as gender [6], age [7], sitting for long periods [8], working at computers [9], school seating [10] and psychological factors [11].

Epidemiology

There has been a high prevalence of low back pain (LBP) in adolescents demonstrated in a number of epidemiological studies [12]. Estimates of the prevalence of back pain in children adolescents vary greatly, ranging from 30%-70% [13][14]. The study by Jeffries et al (2007) found a life time prevalence ranging from 4.7% to 74.4% for spinal or back pain and 7% to 72% for LBP[7]. These ranges depend on the age of the participants and the methodological differences, in particular the definition of back pain used[3].

This level of prevalence raises concerns due to the link between LBP in adolescents and chronic LBP in adulthood[15]. A history of symptoms has been found to be the strongest predictor of future LBP[16] and an early onset in life linked to chronicity[17][5]. It has been found that the occurrence of back pain in adolescents increases with age, in particular in the years of early teens[7].

Growth and development of males and females is remarkably similar up to approximately the age of 10[18]. Above the age of 10, as a result of puberty, the growth patterns of males and females deviate considerably[18]. By at least the age of 18 or 19 years, puberty is considered to have ceased[7]. With the potential influence of puberty related growth on the incidence of adolescent back pain [19] it is imperative that the range of pubertal ages are taken into consideration in epidemiological studies[7].

Aetiology

Treatment

Treatment of LBP in adults has been investigated extensively (Calvo). Evidence has shown that physiotherapy treatment with exercise, back school and manual therapy are effective in reducing pain and functional limitations in adults (Heymans et al and Aure). A study looking at low back pain in adolescent athletes suggested that despite undergoing pubescent changes into adulthood, adolescents cannot be treated like young adults. Therefore, treatment of adolescents can be difficult and must be approached differently, with good understanding of spinal development (De Luigi).

Investigation and practice of therapeutic treatments for children and adolescents with back pain is more recent than with adults (Calvo-Muñoz). Treatments used include back education, exercise, manual therapy and therapeutic conditioning. These interventions are primarily aimed at decreasing the prevalence, and lessening the intensity of LBP and disability (Calvo-Muñoz).

Preventative treatments have been carried out over the last 3 decades, including physical therapy exercises, postural hygiene and the promotion of physical activity (Calvo-Muñoz). According to Curtis and d’Hemecourt (2007) the best prevention of back pain is early detection. Preventative measures can include ‘proper technique’ e.g. in lifting sports and limiting excessive lumbar lordosis, plus participating in core-strengthening exercises and stretches for tight hamstrings and hip flexors which also may help reduce the risk of low back pain (Purcell).

Some literature suggests that back packs carried by schoolchildren can cause back pain if they are to heavy or if the weight is carried unevenly. (?NHSCHOICES) According to this group-randomised control trial the following should be advised to prevent LBP:

- Load the minimum weight possible

- Carry a school backpack on two shoulders

- Correct the belief that school backpack weight does not affect the back

- Using a locker at school

(Vidal, 2013)

The study found that children were able to learn healthy backpack habits. However, this study was in primary school aged children rather than secondary, therefore results may not be generalisable for an adolescent population.

It has been concluded that physiotherapy treatments seem to be effective in adolescents with LBP (Calvo-Muñoz).

Suggested treatments for the rehabilitation of adolescents with back pain include:

- Back education (theoretical or practical)- acquisition of knowledge, posture training habits, body awareness training

- Exercise- including stretching, strengthening, breathing, posture correction, balance exercises, functional exercises, warm-up, relaxation, coordination, stabilisation.

A study which evaluated the efficacy of an exercise program for recurrent non-specific back pain in adolescents, concluding that an exercise was an effective short-term treatment strategy, incorporated the following forms of exercise:

a) Pain relieving exercises which encourage motion of the lumbar spine to reduce joint stiffness such as the ‘cat stretch’ and flexibility exercises for the hip and knee, such as knees to chest and knees to the side

b)Reconditioning exercises aiming to provide muscle endurance of lumbar stabilisers and help encourage appropriate motor control of muscle recruitment such as ‘superman’ single leg extension holds in ?4 point kneeling.

c) Progressive exercises imposing a higher challenge on the lumbar stabilisers and more strength related activities, for instance horizontal side support on feet.

Manual therapy- mobilisation, manipulation, massage

- Therapeutic physical conditioning- walking, running, swimming, cycling.

(Calvo-Muñoz).

A meta analysis in 2013 examined the differential effectiveness of physiotherapy treatment for LBP in children and adolescents aiming to determine whether the treatments were beneficial for pain and disability among other outcome variables. Prior to this analysis, there was no solid evidence to suggest which treatment was most effective for adolescents with back pain.

All the treatment outcome measures reached a statistically significant effect magnitude and showed a clinically relevant improvement of symptoms. The most effective combination treatment was therapeutic physical conditioning (ie general fitness) and manual therapy. However, there was limited details of what the treatments actually involved.

Intensity and duration of treatment

The study found that the average:

- number of weeks of treatment was 12

- time a week spent engaging in treatment was 1 hour

Quality of the study

The meta-analysis itself has good methodological quality, however, there was a low number of applicable studies with only 8 articles met the selection criteria. There was also a lack of control groups and methodological quality of the studies was poor. This prevents definite conclusions being drawn. Furthermore, no evidence was provided regarding the duration of the beneficial effects, or details of follow up.

According to Jones et al, 2007 and Cardon et al 2007, there is a need to incorporate back care and exercise into physical education curricula in schools.

Interestingly, an RCT by Ahlqwist (2008) found that an active physiotherapy program improved adolescent experience of back pain regardless of whether the program consisted of supervised exercises by a physiotherapist.

Conclusion

References

- ↑ Who.int. WHO | Adolescent health [Internet]. 2015 [cited 9 January 2015]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/adolescent_health/en/

- ↑ Unfpa.org. UNFPA - United Nations Population Fund | State of World Population 2003 [Internet]. 2003 [cited 12 January 2015]. Available from: http://www.unfpa.org/publications/state-world-population-2003

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Jones G, Macfarlane G. Epidemiology of low back pain in children and adolescents. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2005;90(3):312-316.

- ↑ Burton A, Clarke R, McClune T, Tillotson K. The Natural History of Low Back Pain in Adolescents. Spine. 1996;21(20):2323-2328.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Harreby M, Neergaard K, Hesselsôe G, Kjer J. Are Radiologic Changes in the Thoracic and Lumbar Spine of Adolescents Risk Factors for Low Back Pain in Adults?. Spine. 1995;20(21):2298-2302.

- ↑ Grimmer K, Nyland L, Milanese S. Longitudinal investigation of low back pain in Australian adolescents: a five-year study. Physiother Res Int. 2006;11(3):161-172.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Jeffries L, Milanese S, Grimmer-Somers K. Epidemiology of Adolescent Spinal Pain. Spine. 2007;32(23):2630-2637.

- ↑ Grimmer K, Williams M. Gender-age environmental associates of adolescent low back pain. Applied Ergonomics. 2000;31(4):343-360.

- ↑ Hakala P, Rimpela A, Saarni L, Salminen J. Frequent computer-related activities increase the risk of neck-shoulder and low back pain in adolescents. The European Journal of Public Health. 2005;16(5):536-541.

- ↑ Troussiere B, Tesniere C, Fauconnier J, Grison J, Juvin R, Phelip X. Comparative study of two different kinds of school furniture among children. Ergonomics. 1999;42(3):516-526.

- ↑ Astfalck R, O'Sullivan P, Straker L, Smith A. A detailed characterisation of pain, disability, physical and psychological features of a small group of adolescents with non-specific chronic low back pain. Manual Therapy. 2010;15(3):240-247.

- ↑ Pellisé F, Balagué F, Rajmil L, Cedraschi C, Aguirre M, Fontecha C et al. Prevalence of Low Back Pain and Its Effect on Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics &amp; Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(1):65.

- ↑ Balagué F, Troussier B, Salminen J. Non-specific low back pain in children and adolescents: risk factors. European Spine Journal. 1999;8(6):429-438.

- ↑ Wedderkopp N, Leboeuf-Yde C, Andersen L, Froberg K, Hansen H. Back Pain Reporting Pattern in a Danish Population-Based Sample of Children and Adolescents. Spine. 2001;26(17):1879-1883.

- ↑ Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik K, Manniche C. The Course of Low Back Pain From Adolescence to Adulthood. Spine. 2006;31(4):468-472.

- ↑ Papageorgiou A, Croft P, Thomas E, Ferry S, Jayson M, Silman A. Influence of previous pain experience on the episode incidence of low back pain: results from the South Manchester Back Pain Study. Pain. 1996;66(2-3):181-185.

- ↑ Brattberg G. The incidence of back pain and headache among Swedish school children. Qual Life Res. 1994;3(S1):S27-S31.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Brundtland G, Liestol K, Walloe L. Height and weight of school children and adolescent girls and boys in Oslo 1970. Acta Paediatrica. 1975;64(4):565-573.

- ↑ Feldman D. Risk Factors for the Development of Low Back Pain in Adolescence. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;154(1):30-36.