Acute Coronary Syndrome: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

== Definition/Description == | == Definition/Description == | ||

[[File:ACS scheme.jpeg|right|frameless|399x399px]] | [[File:ACS scheme.jpeg|right|frameless|399x399px]] | ||

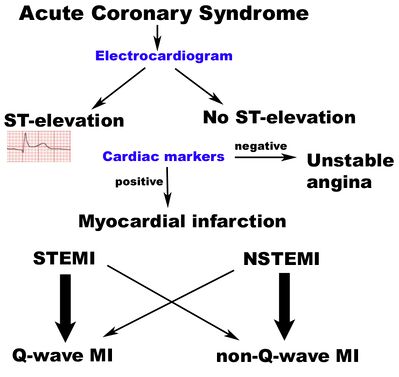

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a group of cardiac diagnoses along a spectrum of severity due to the interruption of coronary blood flow to the myocardium, which in decreasing severity are: | Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a group of cardiac diagnoses along a spectrum of severity due to the interruption of [[Coronary Artery|coronary blood flow]] to the myocardium, which in decreasing severity are: | ||

# ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI): | # ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI): Very serious type of heart attack during which one of the heart’s major arteries is blocked. The classic heart attack. | ||

# Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI): | # Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI): The "intermediate" form of ACS, a blockage either occurs in a minor coronary artery or causes partial obstruction of a major coronary artery. Symptoms can be the same as STEMI but the heart damage is far less extensive<ref>Very Well Health [https://www.verywellhealth.com/non-st-segment-elevation-myocardial-infarction-nstemi-1746017 Non-ST Segment Myocardial Infarction] Overview Available from:https://www.verywellhealth.com/non-st-segment-elevation-myocardial-infarction-nstemi-1746017 (accessed 26.5.2021)</ref>. | ||

# Unstable angina: Thrombus partially or intermittently occludes the coronary artery. | # Unstable angina: Thrombus partially or intermittently occludes the coronary artery. | ||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

Of all patients who present to emergency departments with symptoms of ACS, only 20-25% will have ACS confirmed as their discharge diagnosis.<ref name=":0" /> | Of all patients who present to emergency departments with symptoms of ACS, only 20-25% will have ACS confirmed as their discharge diagnosis.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

* Acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and sudden death cause most ischaemic heart disease(IHD)-related deaths, which represent 1.8 million deaths per year. | |||

* The incidence of IHD in general, and of ACS, increases with age although, on average, this occurs 7–10 years earlier in men compared with women. | |||

* ACS occurs far more often in men than in women below the age of 60 years but women represent the majority of patients over 75 years of age. | |||

* The risk of acute coronary events in life is related to the exposure to traditional cardiovascular risk factors. | |||

* Huge differences within European and world regions can be found in the incidence and prevalence of IHD and ACS as well as in case fatality rates.<ref>Davies MJ. The pathophysiology of acute coronary syndromes. Heart. 2000 Mar 1;83(3):361-6.Available from: https://oxfordmedicine.com/view/10.1093/med/9780198784906.001.0001/med-9780198784906-chapter-305<nowiki/>Accessed 26.5.2021</ref>.<br> | |||

== Aetiology == | |||

[[File:Atherosclerosis diagram.png|right|frameless]] | |||

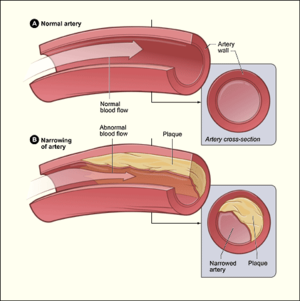

The most common cause by far is [[Atherosclerosis|atherosclerotic plaque]] rupture in coronary artery disease. Other less common causes include: | |||

# Aortic or coronary artery dissection | |||

# Vasculitis | |||

# [[Connective Tissue Disorders|Connective tissue disorders]] | |||

# Drugs: [[Prescription Drug Abuse (Narcotic Painkillers)|cocaine]] | |||

# Coronary artery spasm<ref name=":0" /><br> | |||

[[ | |||

== Investigations == | == Investigations == | ||

Revision as of 07:47, 26 May 2021

Original Editor - Haseel Bhatt

Top Contributors - Haseel Bhatt, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Adam Vallely Farrell, Admin, Michelle Lee, 127.0.0.1 and WikiSysop

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a group of cardiac diagnoses along a spectrum of severity due to the interruption of coronary blood flow to the myocardium, which in decreasing severity are:

- ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI): Very serious type of heart attack during which one of the heart’s major arteries is blocked. The classic heart attack.

- Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI): The "intermediate" form of ACS, a blockage either occurs in a minor coronary artery or causes partial obstruction of a major coronary artery. Symptoms can be the same as STEMI but the heart damage is far less extensive[1].

- Unstable angina: Thrombus partially or intermittently occludes the coronary artery.

Stable angina is not considered an ACS.[2][3]

ACS is a type of coronary artery disease (CAD), which is responsible for one-third of total deaths in people older than 35. Some forms of CAD can be asymptomatic, but ACS is always symptomatic.[4]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Of all patients who present to emergency departments with symptoms of ACS, only 20-25% will have ACS confirmed as their discharge diagnosis.[2]

- Acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and sudden death cause most ischaemic heart disease(IHD)-related deaths, which represent 1.8 million deaths per year.

- The incidence of IHD in general, and of ACS, increases with age although, on average, this occurs 7–10 years earlier in men compared with women.

- ACS occurs far more often in men than in women below the age of 60 years but women represent the majority of patients over 75 years of age.

- The risk of acute coronary events in life is related to the exposure to traditional cardiovascular risk factors.

- Huge differences within European and world regions can be found in the incidence and prevalence of IHD and ACS as well as in case fatality rates.[5].

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

The most common cause by far is atherosclerotic plaque rupture in coronary artery disease. Other less common causes include:

- Aortic or coronary artery dissection

- Vasculitis

- Connective tissue disorders

- Drugs: cocaine

- Coronary artery spasm[2]

Investigations[edit | edit source]

Imaging Techniques

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

- In the setting of acute chest pain, the electrocardiogram is the investigation that most reliably distinguishes between various causes.

- If this indicates acute heart damage (elevation in the ST segment, new left bundle branch block)

- Non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) are reflected on EMG

- In the absence of such changes, it is not possible to immediately distinguish between unstable angina and NSTEMI.

Echocardiography

- Echocardiography is highly portable, and relatively inexpensive compared with other noninvasive modalities.

- It on detecting wall motion changes, which occur when myocardial blood flow falls below resting levels. Often this occurs when coronary obstruction exceeds 85–90% of the luminal area.

- Echocardiography is a class I indication to evaluate RWMA in patients presenting with chest pain but with low-to-intermediate risk.[6]

Computed Tomography

- MDCT has the ability to identify plaque area and the degree of stenosis.

- The sensitivity of MDCT to detect CAD has been reported to be 73–100% with a specificity of 91–97%.[6]

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- CMR has clear roles in the congenital heart disease, chronic CAD, myocardial and pericardial diseases, and imaging of the great vessels.

- It has a sensitivity of 84% and a specificity of 85%, which is greater than EKG or troponin

- Cine imaging can assess global and regional left ventricular function, and its accurate and reproducible ventricular volumes and functions make it more accurate than other noninvasive methods

- First pass myocardial perfusion utilises a contrast agent co-administered with a vasodilator-like adenosine to delineate under perfused areas highlighting sub-endocardial ischemia.[6]

Positron Emission Tomography

- PET is able to identify functional metabolic activity by imaging glucose utilisation.

- Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) once injected is taken up by cells that utilise glucose for metabolism, and the more metabolic activity of the tissue the greater the amount of FDG, taken up. As FDG decays gamma rays are emitted and the position of origin is imaged by PET imaging.

- Imaging with PET in ACS relies on the ability to detect acute inflammation. Atherosclerotic coronary plaques are characterised by macrophage accumulation. FDG uptake is increased in these areas as macrophages often take up more glucose than the surrounding tissues.[6]

Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography

- SPECT utilises myocardial perfusion imaging to asses arterial health

- Resting and stress myocardial perfusion imaging in patients with low-to-intermediate risk for CAD will identify active inducible ischemia.

- However, in patients with recent angina symptoms SPECT may not be able to identify recent and old infarcts limiting its specificity.

- SPECT is more sensitive than exercise treadmill testing alone for detecting coronary artery stenosis.[6]

Clinical Manifestations[edit | edit source]

The extent to which a coronary artery is occluded often correlates with presenting symptoms and diagnostic findings[7]. Angina or chest pain is considered the cardinal symptom of ACS. Other symptoms that are commonly associated with ACS include; pain with or without radiation to left arm, neck, back or epigastric area, shortness of breath (SOB), diaphoresis, nausea and light headedness. It is important to note that women often present with atypical symptoms which may ultimately delay diagnosis and treatment.[7] These clinical manifestations include; fatigue, lethargy, indigestion, anxiety and pain radiating down the back.[7]

Physiotherapy and Other Management[edit | edit source]

Reperfusion therapy

- Diagnosis of STEMI requires emergent reperfusion therapy to restore normal blood flow through coronary arteries and limit infarct size.

- PCI is associated with reduced mortality of approx. 30% and decreased risk of intracranial haemorrhage and stroke which makes it the best choice for elderly and those at risk for bleeding.

- In optimal circumstances, the usage of PCI is able to achieve restored coronary artery flow in >90% of subjects. Fibrinolytic's restores normal coronary artery flow in 50–60% of subjects.[8]

Oxygen

- Supplemental oxygen should be given to patients with signs of breathlessness, heart failure, shock, or an arterial oxyhemoglobin saturation <94%.[8]

Nitroglycerin

- Nitroglycerin has beneficial effects during suspected cases of ACS. It dilates the coronary arteries, peripheral arterial bed, and venous capacitance vessels.

- The administration of nitroglycerin should be carefully considered in cases when administration would exclude the use of other helpful medications.

- Patients with ischemic discomfort receive up to 3 doses (0.4 mg) over 3–5 min intervals, until chest discomfort is relieved or low blood pressure limits its use.

- Nitroglycerin may be administered intravenously, orally, or topically. Clinicians should be cautious in cases of known inferior wall STEMI and suspected right ventricular involvement because patients require adequate right ventricle preload. A right-sided ECG should be performed to rule out right ventricular ischemia.[8]

Anti-Platelet therapy

- This is common management provided by other healthcare professionals.

- This generally involves the utilisation of medications, predominately in tablet form. These drugs can be aspirin, adenosine diphosphate ADP)-receptor blockers and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, among others.[3]

1)Aspirin

- Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid [ASA]) blocks the synthesis of TxA2 from arachidonic acid via its inhibition of the cyclooxyrgenase (COX) enzyme.

- It is the oldest and most studied anti-platelet agent, with early clinical trials in ACS showing consistent benefit over placebo or untreated control for reducing the risk of death and recurrent MI.[3]

2)Adenosine Diphosphate-Receptor Antagonists

- The joint interaction of ADP with its P2Y1 and P2Y12 receptors not only induces platelet aggregation but also amplifies the platelet response through enhanced secretion of, and response to, platelet agonists such as TxA2 and thrombin.

- Clopidogrel and other thienopyridines, have become increasingly important in the management of ACS.[3]

3)Ticlopidine

- Ticlopidine was developed as the original ADP P2Y12 receptor antagonist.

- It is equivalent to aspirin in the prevention of secondary vascular events in patients with ACS.

- The concept of combining ASA and a thienopyridine for ACS management was first assessed using ticlopidine, with several studies in patients with PCI demonstrating the benefit of dual anti-platelet therapy over ASA alone or ASA plus warfarin.[3]

4)Clopidogrel

- Clopidogrel in recent studies has shown greater benefit in patients as opposed to aspirin therapy.[3]

Beta blockers

- β-Adrenergic receptor blockers have shown to reduce mortality and decrease infarct size with early intravenous usage and can prevent arrhythmias.

- β-Blockers reduce myocardial workload and oxygen demand by reducing contractility, heart rate, and arterial blood pressure.[8]

Anticoagulation

- Anticoagulant medications such as unfractionated heparin (UFH), low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), or less commonly bivalirudin have been shown to decrease reinfarction following reperfusion therapy.[8]

Prevention and Lifestyle modification[edit | edit source]

Acute coronary syndrome can best be prevented by better controlling modifiable risk factors such as; diet, exercise, management of hypertension and diabetes and smoking cessation. In accordance with the NICE guidelines, clinicians should advise people to eat a Mediterranean-style diet, be physically active for 20-30 minutes a day to the point of slight breathlessness, and provide assistance of smoking cessation interventions. Policy changes have taken effect in Scotland which showed a significant decrease the number of admissions for Acute Coronary Syndrome as a result of the The Smoking, Health and Social Care Act which prohibited smoking in all enclosed public places and workplaces. Cardiac rehabilitation and education can improve mortality outcomes

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Very Well Health Non-ST Segment Myocardial Infarction Overview Available from:https://www.verywellhealth.com/non-st-segment-elevation-myocardial-infarction-nstemi-1746017 (accessed 26.5.2021)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Radiopedia ACS Available: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/acute-coronary-syndrome(accessed 26.5.2021)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Aragam, K.G. & Bhatt, D.L., 2011. Antiplatelet therapy in acute coronary syndromes. Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology and therapeutics, 16(1), pp.24–42

- ↑ Singh A, Museedi AS, Grossman SA. Acute coronary syndrome.Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459157/(accessed 26.5.20210

- ↑ Davies MJ. The pathophysiology of acute coronary syndromes. Heart. 2000 Mar 1;83(3):361-6.Available from: https://oxfordmedicine.com/view/10.1093/med/9780198784906.001.0001/med-9780198784906-chapter-305Accessed 26.5.2021

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Zimmerman, S.K. & Vacek, J.L., 2011. Imaging Techniques in Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Review. ISRN Cardiology, 2011, pp.1–6.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Overbaugh, B.K.J., 2009. Acute coronary syndrome. Ajn, 109(5), pp.42–52.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Davies, M.J., 2000. The pathophysiology of acute coronary syndromes. Heart (British Cardiac Society), 83, pp.361–366.