Acne Vulgaris

Original Editor - Aya Alhindi

Top Contributors - Aya Alhindi, Kim Jackson and Lucinda hampton

This article or area is currently under construction and may only be partially complete. Please come back soon to see the finished work! (19/04/2023)

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Acne is a chronic inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous unit can be caused by androgen-induced increased sebum production, altered keratinisation, inflammation, and bacterial colonisation of hair follicles on the face, neck, chest, and back by Propionibacterium acnes. The distribution of acne corresponds to the highest density of pilosebaceous units (face, neck, upper chest, shoulders, and back). [1]

The clinical features of acne include:

- Seborrhoea (excess grease)

- Non-inflammatory lesions (open and closed comedones)

- Inflammatory lesions (papules and pustules)

- Various degrees of scarring.

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

- Acne can start in adolescence and last until the early thirties.

- Males are more likely than females to suffer from acne.

- The urban population is more affected than the rural population.

- Around 20% of those impacted have severe acne, which leads to scarring.

- Some races appear to be hit harder than others. Asians and Africans are more prone to severe acne, whilst whites are more prone to mild acne.

- Hyperpigmentation is more common among populations with darker skin.

- Acne can develop in newborns, but it usually disappears on its own.[2]

Causes[edit | edit source]

There are several factors that contribute to the development of acne vulgaris, including:

- Diet: Several studies have suggested a link between certain dietary factors and the development of acne. For example, high glycemic load diets (i.e., diets that contain a lot of sugar and refined carbohydrates) may exacerbate acne by increasing insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) levels, which can stimulate sebum production and contribute to inflammation. Dairy products have also been implicated in acne, possibly due to their high levels of hormones and growth factors.[3]

- Hormones: Hormonal changes, such as those that occur during puberty, menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause, can trigger acne by increasing oil production in the skin.[4][5]

- Genetics: Acne can be inherited, meaning if your parents or siblings have acne, you are more likely to develop it.[6]

- Stress: Psychological stress has been shown to worsen acne in some people, possibly through the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and subsequent increases in sebum production and inflammation.[7]

- Medications: Some medications, including corticosteroids, lithium, and certain anticonvulsants, can cause or worsen acne.

- Cosmetics: Certain cosmetics, especially those that are oily or greasy, can clog pores and contribute to acne development.

- Bacteria: The bacteria Propionibacterium acnes is naturally present on the skin, but when it overgrows in hair follicles, it can contribute to the development of acne.[8]

- Dysbiosis of the skin microbiome: Recent studies have shown that dysbiosis of the skin microbiome (the community of microorganisms that inhabit the skin) can contribute to the development of acne. Dysbiosis occurs when there is an imbalance between the "good" and "bad" bacteria on the skin, leading to the overgrowth of certain bacterial species that can trigger inflammation and acne lesions. This new understanding of acne pathogenesis has led to the development of novel treatments that target the skin microbiome to restore a healthy balance of microorganisms.[9]

- Environmental factors: Exposure to certain environmental pollutants, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), has been linked to the development of acne. PAHs are found in air pollution, cigarette smoke, and certain occupational settings, and may contribute to inflammation and oxidative stress in the skin. [10]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

- Acne vulgaris pathophysiology is complicated, including both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. The fundamental reason, however, is excessive sebum production and abnormal epithelial cell desquamation.[11]

- The formation of the microcomedo, or blocking of the follicular canal, is one of the first events in the progression of acne lesions. [11]

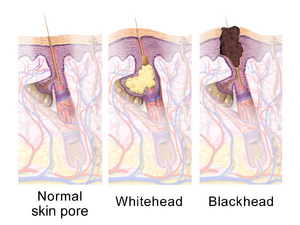

- Keratin and sebum accumulate in the follicle due to increased corneocyte cohesiveness and hyperkeratosis of the follicular lining. This results in the formation of a plug (comedo) above the sebaceous gland duct. The comedo swells behind a small follicular opening to the skin as these cells continue to pack into the follicle.This results in:[11]

- Distension of the follicle and formation of a closed comedone (firm, elevated, white or yellow papule).

- Dilation of the pores at the surface of the skin due to this retention keratosis,resulting in an open comedone (blackhead).

- The closed comedone is a precursor to the inflammatory acne lesions. As the expanding comedone increases the strain within the follicle, the comedo wall eventually ruptures, resulting in the outflow of keratin and sebum, as well as subsequent skin irritation.[11]

- The most common bacteria associated with acne is Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes). It is a member of the typical skin flora and lives in the pilosebacous follicle. However, P. acnes plays an important role in acne vulgaris because the bacteria contributes significantly to the inflammation and irritation associated with acne.[12]

- Acne is frequently associated with the onset of puberty and increased sex hormone production. The severity of acne is often related to the degree of sex hormones secreted (which peaks in the mid-teenage years). Females also tend to have an acne flare-up about a week before menstruation.[13]

- Acne can be an indication of hyperandrogenism. Female teenagers and adult women with acne should always be questioned about irregular menstruation, hirsutism, and unexplained weight gain. Polycystic ovarian syndrome testing may then be required. Females with acne that is resistant to conventional treatment or who have severe acne that appears suddenly may benefit from an endocrine examination.[13]

Classification of Acne Vulgaris[edit | edit source]

Acne vulgaris is defined based on the severity and type of lesions present. The Global Acne Grading System (GAGS) and the Pillsbury scale are the two primary classification systems for acne vulgaris.[14]

The Global Acne Grading System (GAGS) classifies acne into four categories:

- Grade 1 (Mild): Mostly non-inflammatory lesions, such as comedones (blackheads and whiteheads), with few papules and pustules.

- Grade 2 (Moderate): A mix of non-inflammatory and inflammatory lesions, such as comedones, papules, and pustules, but with less than 20-30 total lesions.

- Grade 3 (Moderately Severe): Numerous papules and pustules, as well as a few nodules, with 20-100 total lesions.

- Grade 4 (Severe): Numerous nodules and cysts, with more than 100 total lesions.

The Pillsbury scale classifies acne vulgaris based on the type of lesion present:

- Grade 1 (Mild): Comedones (blackheads and whiteheads).

- Grade 2 (Moderate): Comedones and papules.

- Grade 3 (Moderately Severe): Comedones, papules, and pustules.

- Grade 4 (Severe): Comedones, papules, pustules, nodules, and cysts.

Signs and Symptoms[edit | edit source]

- Blackheads (open comedones): small, black or dark brown spots that form when a hair follicle becomes clogged with oil and dead skin cells.

- Whiteheads (closed comedones): small, flesh-colored or white bumps that form when a hair follicle becomes clogged with oil and dead skin cells, but stays closed.

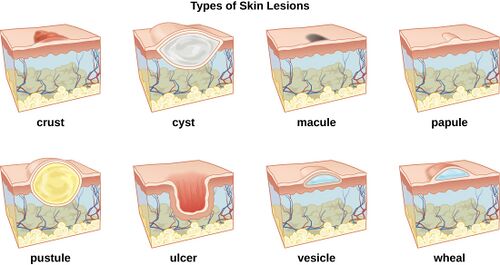

- Papules: small, red or pink bumps that are tender to the touch.

- Pustules: similar to papules, but with a white or yellow center that contains pus.

- Nodules: large, painful bumps that are deeply embedded in the skin.

- Cysts: large, pus-filled bumps that are deeply embedded in the skin and can lead to scarring.

- Other symptoms may include:

- Oily skin

- Scarring

- Redness and inflammation of the skin

- Itching and burning of the skin

- Dark spots or patches on the skin after the acne has cleared (post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation)

Complications[edit | edit source]

While acne is not a life-threatening condition, it can have a significant impact on a person's self-esteem and quality of life. In addition, severe acne can lead to a number of complications. Some of the possible complications of acne vulgaris include:[15]

- Scarring: Acne can leave permanent scars on the skin, which can have a significant impact on a person's self-esteem and quality of life.

- Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation: This is a common complication of acne vulgaris that occurs when the skin produces too much melanin in response to inflammation. This can result in dark spots on the skin that can take months or even years to fade.[16]

- Psychological distress: Acne can cause significant emotional distress, especially in teenagers who are already struggling with issues related to self-image and self-esteem.[17]

- Bacterial infections: In severe cases, acne can lead to bacterial infections, which can cause painful cysts and abscesses.

- Secondary infections: Picking at acne lesions can lead to secondary infections, which can be more serious and difficult to treat than the original acne.

- Permanent changes in skin texture: Acne can cause permanent changes in the texture of the skin, including enlarged pores and rough or uneven skin.

- Delayed healing: Acne lesions can take a long time to heal, especially if they are deep or cystic. [18]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Acne conglobata

- Acne fulminans

- Acne Keloidalis nuchae

- Acneiform eruptions

- Folliculitis

- Perioral Dermatitis

- Rosacea

- Sebaceous Hyperplasia

- Syringoma

- Tuberous Sclerosis

Assessment[edit | edit source]

Assessment of acne vulgaris involves:[19]

Comprehensive evaluation of the patient's medical history[edit | edit source]

Which includes:

- The patient's current and previous medical conditions.

- Medications.

- Skin care products used.

- The patient's family history of acne, as genetic factors can play a role in the development of acne.

- Allergies.

- Menstrual history.

- Lifestyle factors such as diet and stress.

Physical examination[edit | edit source]

The examination involves looking for:

- the presence of different types of acne lesions such as comedones, papules, pustules, nodules, and cysts.

- signs of scarring and pigmentation changes.

- general skin examination to identify any other skin conditions that may be present.

Assessment of lesion type and severity[edit | edit source]

The dermatologist will use either the Global Acne Grading System (GAGS) or the Pillsbury scale to evaluate the type and severity of acne lesions present.

Assessment of psychosocial impact[edit | edit source]

Laboratory tests[edit | edit source]

These may include blood tests to check for hormonal imbalances or other medical conditions that can cause acne.

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Pharmalogic Agents[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy role[edit | edit source]

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Williams HC, Dellavalle RP, Garner S. Acne vulgaris. Lancet [Internet]. 2012;379(9813):361–72. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673611603218

- ↑ Sutaria AH, Masood S, Schlessinger J. Acne Vulgaris. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- ↑ Burris J, Rietkerk W, Woolf K. Relationships of self-reported dietary factors and perceived acne severity in a cohort of New York young adults. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2020;120(3):386-96. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2019.09.013. PMID: 31712195.

- ↑ Bhate K, Williams HC. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(3):474-85. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12149. PMID: 23210645.

- ↑ Katsambas A, Dessinioti C. Hormonal therapy for acne: A review of current and future therapies. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011;3(3):188-96. doi: 10.4161/derm.3.3.16844. PMID: 22110847.

- ↑ Zouboulis CC. Acne and sebaceous gland function. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22(5):360-6. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2004.03.001. PMID: 15556719.

- ↑ Kouris A, Platsidaki E, Christodoulou C, Efstathiou V, Dessinioti C, Antoniou C, et al. Quality of life, depression, anxiety and loneliness in patients with acne vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(2):298-301. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14655. PMID: 28626904.

- ↑ Gollnick H, Cunliffe W. Bacteria in acne vulgaris. In: Zouboulis CC, Katsambas A, Kligman AM, editors. Pathogenesis and Treatment of Acne and Rosacea. 1st ed. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2014. p. 93-103. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-45139-7_9.

- ↑ Barnard E, Shi B, Kang D, Craft N, Li H. The balance of metagenomic elements shapes the skin microbiome in acne and health. Sci Rep. 2016;6:39491. doi: 10.1038/srep39491. PMID: 28008919.

- ↑ Kim J, Kwon SH, Hwang YJ, et al. Association between outdoor air pollution and the prevalence of acne in adolescents. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33(41):e258. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e258. PMID: 30344467.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Well D. Acne vulgaris: A review of causes and treatment options. Nurse Pract [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2023 Apr 18];38(10):22–31. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/tnpj/FullText/2013/10000/Acne_vulgaris__A_review_of_causes_and_treatment.6.aspx

- ↑ Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2004:162–194.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2006:231–239.

- ↑ Katsambas, A., & Dessinioti, C. (2010). New and emerging treatments in dermatology: acne. Dermatology, 221(1), 104-110. https://doi.org/10.1159/000312818

- ↑ James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016. Chapter 13.

- ↑ Davis EC, Callender VD. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: a review of the epidemiology, clinical features, and treatment options in skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3(7):20-31

- ↑ Dessinioti C, Katsambas A. Psychological implications of acne vulgaris: a critical review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(5):763-769.

- ↑ Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5):945-973.e33.

- ↑ Del Rosso, J. Q. (2013). The role of skin care as an integral component in the management of acne vulgaris: part 1: the importance of cleanser and moisturizer ingredients, design, and product selection. The Journal of clinical and aesthetic dermatology, 6(12), 19-27.