Dyspareunia: Difference between revisions

(Updated "History Taking") |

(Updated "Clinically Relevant Anatomy") |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | == Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | ||

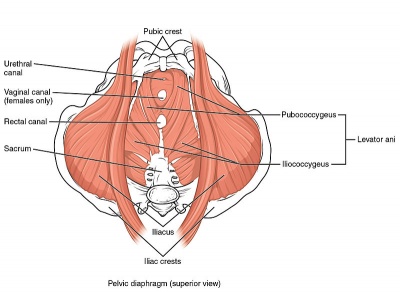

[[Image:Pelvic Floor Muscles.jpg|400px|thumb|Pelvic diaphragm (superior view)]] | [[Image:Pelvic Floor Muscles.jpg|400px|thumb|Pelvic diaphragm (superior view)]] | ||

Weakness in deep [[Pelvic Floor Anatomy|pelvic floor muscles]] ([[Levator Ani Muscle|levator ani]] muscle group and [[coccygeus]]) can cause deep dyspareunia. <ref>Edwards L. Vulvodynia. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2015 Mar 1;58(1):143-52.</ref><ref name=":6" /><ref name=":7" /> | |||

The [[Pudendal Nerve|pudendal nerve]] (composed of somatic branches from the [[Sacral Plexus|sacral plexus]], specifically S2 to S4 <ref name=":8">Prather H, Dugan S, Fitzgerald C, Hunt D. Review of anatomy, evaluation, and treatment of musculoskeletal pelvic floor pain in women. PM&R. 2009 Apr 1;1(4):346-58. | |||

</ref> <ref>Standring S. Gray’s Anatomy 41st Edition: Churchill Livingstone.</ref> <ref name=":9">Woodman PJ, Graney DO. Anatomy and physiology of the female perineal body with relevance to obstetrical injury and repair. Clinical Anatomy: The Official Journal of the American Association of Clinical Anatomists and the British Association of Clinical Anatomists. 2002 Aug;15(5):321-34.</ref><ref>Ventolini G. Vulvar pain: anatomic and recent pathophysiologic considerations. Clinical Anatomy. 2013 Jan;26(1):130-3.</ref>) is one of most important nerves associated with dyspareunia or pelvic pain. Due to its location in the pelvis, it is susceptible to injury during pelvic surgeries and parturition. <ref name=":8" /><ref name=":9" /> | |||

Entry dyspareunia usually involves the vulva and its surrounding structures <ref name=":7" /> | |||

Deep dyspareunia is characterized by pain experienced during deep vaginal penetration and might involve the inner pelvic structures such as the [[Bladder Anatomy|urinary bladder]] and cervix. <ref name=":7" /><ref name=":6" /> | |||

Please see the page "[[Pelvic Floor Anatomy]]" for further details regarding anatomy. | |||

== Aetiology == | == Aetiology == | ||

| Line 59: | Line 63: | ||

A recent study <ref name=":4" /> summarised important findings related to the history taking: | A recent study <ref name=":4" /> summarised important findings related to the history taking: | ||

* Accurate clinical diagnosis requires detailed information about the location, onset, duration, severity, nature of pain, precipitating factors, and positions associated with the pain. <ref>Howard FM, editor. [https://books.google.com.tr/books?hl=en&lr=&id=6q2xbQiHYWcC&oi=fnd&pg=PA125&dq=Howard+FM,+Perry+CP,+Carter+JE,+El-Minawi+AM.+2000.+Pelvic+pain:+Diagnosis+and+management.+Philadelphia:+Lippincott+Williams+%26+Wilkins.+p+1-529.&ots=fesNXkzE44&sig=QW_PD4msZY8SE55ui9Q24o7Amno&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false Pelvic pain: diagnosis and management]. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000.</ref><ref>Seehusen DA, Baird DC, Bode DV. [https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/1001/p465.html Dyspareunia in women]. American family physician. 2014 Oct 1;90(7):465-70.</ref> | * Accurate clinical diagnosis requires detailed information about the location, onset, duration, severity, nature of pain, precipitating factors, and positions associated with the pain. <ref name=":7">Howard FM, editor. [https://books.google.com.tr/books?hl=en&lr=&id=6q2xbQiHYWcC&oi=fnd&pg=PA125&dq=Howard+FM,+Perry+CP,+Carter+JE,+El-Minawi+AM.+2000.+Pelvic+pain:+Diagnosis+and+management.+Philadelphia:+Lippincott+Williams+%26+Wilkins.+p+1-529.&ots=fesNXkzE44&sig=QW_PD4msZY8SE55ui9Q24o7Amno&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false Pelvic pain: diagnosis and management]. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000.</ref><ref name=":6">Seehusen DA, Baird DC, Bode DV. [https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/1001/p465.html Dyspareunia in women]. American family physician. 2014 Oct 1;90(7):465-70.</ref> | ||

* It is particularly helpful to know the specific location of the pain, especially if it is localized to the vulva, vagina introitus, or inside of the vagina, as this can help narrow down the possible causes. | * It is particularly helpful to know the specific location of the pain, especially if it is localized to the vulva, vagina introitus, or inside of the vagina, as this can help narrow down the possible causes. | ||

* In his article on the clinical approach to dyspareunia, Graziottin provides a comprehensive guide to the necessary questions for a thorough history and physical examination. <ref>Graziottin A. Clinical approach to dyspareunia. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2001 Oct 1;27(5):489-501.</ref> | * In his article on the clinical approach to dyspareunia, Graziottin provides a comprehensive guide to the necessary questions for a thorough history and physical examination. <ref>Graziottin A. Clinical approach to dyspareunia. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2001 Oct 1;27(5):489-501.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 15:57, 11 September 2023

This article is currently under review and may not be up to date. Please come back soon to see the finished work! (11/09/2023)

Definition[edit | edit source]

Dyspareunia is defined as persistent genital pain that occurs during sexual intercourse.[1] It can be classified into two types based on the location of the pain – entry or deep dyspareunia. While entry dyspareunia is associated with pain upon an attempt at vaginal penetration at the introitus, deep dyspareunia is pain perceived upon vaginal penetration and causes include adenomyosis, endometriosis, vaginal scarring, interstitial cystitis, and pelvic adhesions. [2]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

The prevalence of dyspareunia varies from 8% to 21.1% globally, as reported by the World Health Organization in 2006. [3]

A recent systematic review concluded the prevalence of dyspareunia as 42% at 2 months, 43% at 2–6 months, and 22% at 6–12 months postpartum. Given these high prevalence as well as impact on a woman's life, the study highlighted to give special attention to the dyspareunia during the postpartum period. [4]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Weakness in deep pelvic floor muscles (levator ani muscle group and coccygeus) can cause deep dyspareunia. [5][6][7]

The pudendal nerve (composed of somatic branches from the sacral plexus, specifically S2 to S4 [8] [9] [10][11]) is one of most important nerves associated with dyspareunia or pelvic pain. Due to its location in the pelvis, it is susceptible to injury during pelvic surgeries and parturition. [8][10]

Entry dyspareunia usually involves the vulva and its surrounding structures [7]

Deep dyspareunia is characterized by pain experienced during deep vaginal penetration and might involve the inner pelvic structures such as the urinary bladder and cervix. [7][6]

Please see the page "Pelvic Floor Anatomy" for further details regarding anatomy.

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

Dyspareunia could be a symptom stemming from one or more of the following:

- skin irritation (i.e. eczema or other skin problems in the genital region)[1]

- endometriosis[12]

- vestibulodynia

- vulvodynia[13]

- vaginismus[12]

- interstitial cystitis[13]

- fibromyalgia[13]

- irritable bowel syndrome[13]

- pelvic inflammatory disease[14]

- depression and/or anxiety[14]

- post-menopause[14]

- postpartum dyspareunia [2]

- inadequate vaginal lubrication or arousal [2]

- anogenital causes such as hemorrhoids and anal fissures [2]

- Bartholin gland infection [2]

- vulvovaginitis [2]

- vaginal atrophy [2]

- adenomyosis [2]

- vaginal scarring [2]

- pelvic adhesions [2]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Individuals may present with pain that occurs at entry during penetration, with deep penetration or pain post-penetration. The patient may also describe pain associated with the insertion of a tampon or during a Pap exam. Words used to describe pain may be (but are not limited to): "throbbing" "burning" or "aching."

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

History Taking[edit | edit source]

A recent study [2] summarised important findings related to the history taking:

- Accurate clinical diagnosis requires detailed information about the location, onset, duration, severity, nature of pain, precipitating factors, and positions associated with the pain. [7][6]

- It is particularly helpful to know the specific location of the pain, especially if it is localized to the vulva, vagina introitus, or inside of the vagina, as this can help narrow down the possible causes.

- In his article on the clinical approach to dyspareunia, Graziottin provides a comprehensive guide to the necessary questions for a thorough history and physical examination. [15]

Another study [3] listed the important elements to discuss during clinical evaluation of female sexual pain as below:

- Pain characteristics: Timing, duration, quality, location, provoked, or unprovoked

- Musculoskeletal history: Pelvic floor surgery, trauma, obstetrics

- Bowel and bladder history: Constipation, diarrhea, urgency, frequency

- Sexual history: Frequency, desire, arousal, satisfaction, relationship

- Psychological history: Mood disorder, anxiety, depression

- History of abuse: Sexual, physical, neglect.

Physical Examination[edit | edit source]

The gold standard to assess the pelvic floor muscles is through an internal exam, performed by a trained medical professional with the informed consent of the patient. This exam allows for the assessment of the health of the tissue, the tonicity of the pelvic floor muscles, the ability to contract and relax these muscles and to assess for vulvodynia and/or vestibulodynia.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

The Female Sexual Destress Scale-Revised (FSDS-R): A single item from this scale may be a useful tool in quickly screening for sexual distress in middle-aged women.[16]

Level of dyspareunia pain (0-10)

Management / Interventions[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapists can address factors contributing to dyspareunia with the following tools and techniques.

| Contributing factor | Tool/Technique |

|---|---|

| Lack of awareness of pelvic floor muscles | Assess the patient's ability to connect with their pelvic floor muscles through their ability to correctly contract and relax their pelvic floor muscles. If the patient is unable to correctly recruit these muscles, whether it be due to lack of strength or neuromotor connection, this should be addressed. |

| Hypertonic pelvic floor muscles | Teaching relaxation techniques for the pelvic floor muscles:

The use of inserts can be beneficial along with these techniques. Teach the patient to move the dilator or insert past the entrance of the vaginal canal in conjunction with relaxing the pelvic floor muscles. |

| Pain centralization | If this has been a chronic issue, addressing principles of centralized pain and explaining this to the patient can be helpful and informative. Additionally, pain at the entrance or through the vaginal canal can elicit a spasm or hypertonic response by the pelvic floor muscles. |

Additional Considerations[edit | edit source]

- The use of a multidisciplinary approach with the inclusion of a physician and a counselling therapist could be beneficial, depending on the reason for experiencing dyspareunia.

- Issues such as fatigue, depression/anxiety, stress or history of abuse can contribute to the tension of the pelvic floor muscles, and this may be addressed through counselling.

- Ensure that the patient has been screened by a physician to rule out any differential diagnoses or address co-existing diagnoses that are out of the physiotherapy scope of practice.

Resources[edit | edit source]

A webinar by "Jean Hailes for Women’s Health" ( a national not-for-profit organisation) on dyspareunia and the physiotherapist's perspective:

A presentation was created by Carolyn Vandyken, a physiotherapist who specializes in the treatment of male and female pelvic dysfunction. She also provides education and mentorship to physiotherapists who are similarly interested in treating these dysfunctions. In the presentation, Carolyn reviews pelvic anatomy, the history of Kegel exercises and what the evidence tells us about when Kegels are and aren't appropriate for our patients.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Mayo Clinic. Painful intercourse. Available from:https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/painful-intercourse/symptoms-causes/syc-20375967 (accessed 13 Feb 2019).

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 Alimi Y, Iwanaga JO, Oskouian RJ, Loukas M, Tubbs RS. The clinical anatomy of dyspareunia: A review. Clinical Anatomy. 2018 Oct;31(7):1013-7.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Sorensen J, Bautista KE, Lamvu G, Feranec J. Evaluation and treatment of female sexual pain: a clinical review. Cureus. 2018 Mar 27;10(3).

- ↑ Banaei M, Kariman N, Ozgoli G, Nasiri M, Ghasemi V, Khiabani A, Dashti S, Mohamadkhani Shahri L. Prevalence of postpartum dyspareunia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2021 Apr;153(1):14-24.

- ↑ Edwards L. Vulvodynia. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2015 Mar 1;58(1):143-52.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Seehusen DA, Baird DC, Bode DV. Dyspareunia in women. American family physician. 2014 Oct 1;90(7):465-70.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Howard FM, editor. Pelvic pain: diagnosis and management. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Prather H, Dugan S, Fitzgerald C, Hunt D. Review of anatomy, evaluation, and treatment of musculoskeletal pelvic floor pain in women. PM&R. 2009 Apr 1;1(4):346-58.

- ↑ Standring S. Gray’s Anatomy 41st Edition: Churchill Livingstone.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Woodman PJ, Graney DO. Anatomy and physiology of the female perineal body with relevance to obstetrical injury and repair. Clinical Anatomy: The Official Journal of the American Association of Clinical Anatomists and the British Association of Clinical Anatomists. 2002 Aug;15(5):321-34.

- ↑ Ventolini G. Vulvar pain: anatomic and recent pathophysiologic considerations. Clinical Anatomy. 2013 Jan;26(1):130-3.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. When sex is painful. Available from:https://www.acog.org/Patients/FAQs/When-Sex-Is-Painful (accessed 21 Feb 2019).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Reed BD, Harlow SD, Sen A, Edwards RM, Chen D, Haefner HK. Relationship between vulvodynia and chronic comorbid pain conditions. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2012;120(1):145.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Latthe P, Mignini L, Gray R, et al. Factors predisposing women to chronic pelvic pain: systematic review. BMJ. 2006;332:749. Latthe P, Mignini L, Gray R, Hills R, Khan K. Factors predisposing women to chronic pelvic pain: systematic review. BMJ. 2006;332(7544):749-55.

- ↑ Graziottin A. Clinical approach to dyspareunia. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2001 Oct 1;27(5):489-501.

- ↑ Carpenter JS, Reed SD, Guthrie KA, Larson JC, Newton KM, Lau RJ, Learman LA, Shifren JL. Using an FSDS‐R Item to Screen for Sexually Related Distress: A MsFLASH Analysis. Sexual medicine. 2015 Mar;3(1):7-13.

- ↑ Jean Hailes. Webinar: Dyspareunia - The physiotherapist's perspective. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rpIi_1SVTeg

- ↑ Physiopedia. Pelvic Physiotherapy - to Kegel or Not?. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w08iCzxnQBU