Heuristics in Clinical Decision Making: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (24 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | <div class="editorbox"> | ||

'''Original Editor '''- [[User: | '''Original Editor '''- [[User:Merinda Rodseth|Merinda Rodseth]] | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

Clinicians make decisions daily which impact | Clinicians make decisions daily which impact the lives of others.<ref name=":0">Whelehan DF, Conlon KC, Ridgway PF. Medicine and heuristics: cognitive biases and medical decision-making. Irish journal of medical science. 2020 May 14;189:1477-1484.DOI: 10.1007/s11845-020-02235-1</ref> They are forced to continually make decisions despite the uncertainty that often taints the situation and any cognitive limitations.<ref name=":1">Gorini A, Pravettoni G. An overview on cognitive aspects implicated in medical decisions. Eur J Intern Med. 2011 Dec;22(6):547-53.</ref> To achieve this, clinicians mostly rely on heuristics - simple cognitive shortcuts influenced by our cognitive biases - which assists in [[Clinical Decision Making in Physiotherapy Practice|clinical decision making]] (CDM).<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":1" /><ref name=":2">Croskerry P, Singhal G, Mamede S. [https://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/qhc/22/Suppl_2/ii58.full.pdf Cognitive debiasing 1: origins of bias and theory of debiasing]. BMJ quality & safety. 2013 Oct 1;22(Suppl 2):ii58-64. DOI: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002387</ref><ref name=":3">Scott IA, Soon J, Elshaug AG, Lindner R. [https://www.mja.com.au/system/files/issues/206_09/10.5694mja16.00999.pdf Countering cognitive biases in minimising low-value care]. Medical Journal of Australia. 2017 May;206(9):407-11. DOI:10.5694/mja16.00999</ref> The advantage of relying on heuristics is that decisions can be made quickly and are mostly accurate and efficient. <ref name=":1" /><ref name=":3" /><ref name=":4">Tversky A, Kahneman D. [https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/767426.pdf Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. science]. 1974 Sep 27;185(4157):1124-31.</ref> But there is also a disadvantage: they often lead to systematic cognitive errors.<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":2" /><ref name=":4" /> Our cognitive errors are also known as “cognitive biases”.<ref name=":2" /> | ||

== What is | == What is Cognitive Bias? == | ||

Bias is inherent to human judgement | Bias is inherent to human judgement<ref name=":2" /> and can be defined as: | ||

* “the psychological tendency to make a decision based on incomplete information and subjective factors rather than empirical evidence” | * ''“the psychological tendency to make a decision based on incomplete information and subjective factors rather than empirical evidence”''.<ref name=":5">Yuen T, Derenge D, Kalman N. [https://cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/Document/May-2018/JFP06706366.PDF Cognitive bias: Its influence on clinical diagnosis]. J Fam Pract. 2018 Jun 1;67(6):366-72. </ref> | ||

* “predictable deviations from rationality” | * ''“predictable deviations from rationality”''.<ref name=":2" /> | ||

Cognitive biases are evident in CDM when information is inappropriately processed and/or overly focused upon (while ignoring other and more relevant information). This process happens subconsciously with the user unaware of its influence | Cognitive biases are evident in CDM when information is inappropriately processed and/or overly focused upon (while ignoring other and more relevant information). This process happens subconsciously with the user unaware of its influence and mostly happens during automatic [https://physio-pedia.com/Clinical_Decision_Making_in_Physiotherapy_Practice#How_Do_We_Make_Decisions.3F System 1 processing] using heuristics.<ref name=":6">Kinsey MJ, Gwynne SM, Kuligowski ED, Kinateder M. [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Michael_Kinsey2/publication/323556184_Cognitive_Biases_Within_Decision_Making_During_Fire_Evacuations/links/5afcfb590f7e9b98e03e9d5f/Cognitive-Biases-Within-Decision-Making-During-Fire-Evacuations.pdf Cognitive biases within decision making during fire evacuations]. Fire technology. 2019 Mar;55(2):465-85. </ref> A systematic review done by Saposnik et al <ref name=":7">Saposnik G, Redelmeier D, Ruff CC, Tobler PN. [https://bmcmedinformdecismak.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12911-016-0377-1 Cognitive biases associated with medical decisions: a systematic review. BMC medical informatics and decision making.] 2016 Dec;16(1):1-4. DOI:10.1186/s12911-016-0377-1</ref> found that cognitive biases may be associated with diagnostic inaccuracies, but limited information is currently available on the impact on evidence-based care.<ref name=":7" /> | ||

== Heuristics and | == Heuristics and Biases in Medical Practice == | ||

=== Availability heuristic === | === Availability heuristic === | ||

* “Tendency to make likelihood predictions based on what can easily be | * ''“Tendency to make likelihood predictions based on what can easily be remembered.”''<ref name=":8">Dobler CC, Morrow AS, Kamath CC. [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Celia_Kamath/publication/329974098_Clinicians%27_cognitive_biases_A_potential_barrier_to_implementation_of_evidence-based_clinical_practice/links/5d88ef8c458515cbd1b8a306/Clinicians-cognitive-biases-A-potential-barrier-to-implementation-of-evidence-based-clinical-practice.pdf Clinicians’ cognitive biases: a potential barrier to implementation of evidence-based clinical practice]. BMJ evidence-based medicine. 2019 Aug 1;24(4):137-40. DOI:10.1136/bmjebm-2018-111074</ref> | ||

* “More recent and readily available answers and solutions are preferentially favoured because of ease of recall and incorrectly perceived | * ''“More recent and readily available answers and solutions are preferentially favoured because of ease of recall and incorrectly perceived importance.”<ref name=":9">O’Sullivan E, Schofield S. [https://discovery.dundee.ac.uk/ws/files/28431731/Final_Published_Version.pdf Cognitive bias in clinical medicine]. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. 2018 Sep;48(3):225-31. DOI:10.4997/JRCPE.2018.306</ref>'' | ||

* “Tendency to overestimate the frequency of things if they are more easily brought to mind. Things are judged to be more frequently occurring if they come to mind easily, probably because they are remembered without difficulty or because they were recently encountered.” | * ''“Tendency to overestimate the frequency of things if they are more easily brought to mind. Things are judged to be more frequently occurring if they come to mind easily, probably because they are remembered without difficulty or because they were recently encountered.”<ref name=":1" />'' | ||

* “Emotionally charged and vivid case studies that come easily to mind ( | * ''“Emotionally charged and vivid case studies that come easily to mind (i.e. are available) can unduly inflate estimates of the likelihood of the same scenario being repeated.”<ref name=":3" />'' | ||

It is important to note that | It is important to note that most available evidence is not necessarily the most relevant, and events that are easily remembered do not necessarily occur more frequently.<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":8" /> This heuristic is also closely related to the “Base-rate neglect” fallacy: | ||

This heuristic is also closely related to the “Base-rate neglect” fallacy: | * ''“... when the underlying incident rates of conditions or population-based knowledge are ignored as if they do not apply to the patient in question.”<ref name=":9" />'' | ||

* “... when the underlying incident rates of conditions or population-based knowledge are ignored as if they do not apply to the patient in | * ''“...tendency to ignore the true prevalence of a disease, either inflating or reducing its base rate...”''<ref name=":14">Croskerry P, Nimmo GR. [http://www.ajustnhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/croskerry-better-decision-making-2011.pdf Better clinical decision making and reducing diagnostic error]. The journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. 2011 Jun 1;41(2):155-62. DOI: 10.4997/JRCPE.2011.208</ref> | ||

* “...tendency to ignore the true prevalence of a disease, either inflating or reducing its base rate...” | '''<u>Impact</u>''': Base rate neglect overrides the knowledge of the prevalence of disease/conditions, and unnecessary tests are ordered regardless of very low probability.<ref name=":9" /> It can lead to distorted hypothesis generation and thereby result in under-or overestimation of certain diagnoses. It can also heavily influence the types of tests ordered, treatments given and information provided to patients (based on what comes to mind).<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":1" /><ref name=":10">Walston Z. [https://www.zacharywalston.com/podcast/episode/4ad23911/how-do-we-make-clinical-decisions How do we make clinical decisions?] [Accessed on 22 January 2021]</ref> | ||

'''<u>Impact</u>''': Base rate neglect overrides the knowledge of the prevalence of disease/conditions and unnecessary tests are ordered regardless of very low probability | |||

'''<u>Examples</u>''': A physiotherapist who recently attended a course on manipulation will be more inclined to use manipulation in the days following the course | '''<u>Examples</u>''': A physiotherapist who recently attended a course on manipulation will be more inclined to use manipulation in the days following the course.<ref name=":10" /> This is also evident if asked for the name of the capital of Australia. Most people will quickly answer with “Sydney”, whereas Canberra is Australia's capital. As Sydney is generally more well-known, it comes to mind first.<ref>Ehrlinger J, Readinger WO, Kim B. [https://www.onlinecasinoground.nl/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Decision-Making-and-Cognitive-Biases-EhrlingerReadingerKim2015.pdf Decision-making and cognitive biases]. Encyclopedia of mental health. 2016 Jan 1;12. DOI:10.1016/B978-0-12-397045-9.00206-8</ref> Conditions/diseases that are less frequently encountered will be less “available” in the clinician’s mind and, therefore, less likely to be diagnosed.<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":11">Hussain A, Oestreicher J. [https://www.surveyophthalmol.com/article/S0039-6257(17)30115-7/fulltext Clinical decision-making: heuristics and cognitive biases for the ophthalmologist]. Survey of Ophthalmology. 2018 Jan 1;63(1):119-24. DOI:10.1016/j.survophthal.2017.08.007</ref> | ||

'''<u>Mitigators</u>''': Look for refuting evidence in the history and examination that may be less obvious. Ensure a comprehensive knowledge of differential diagnosis. Be attentive to atypical signs and symptoms | '''<u>Mitigators</u>''': Look for refuting evidence in the history and examination that may be less obvious. Ensure a comprehensive knowledge of the differential diagnosis. Be attentive to atypical signs and symptoms indicative of more severe pathology and consult with colleagues on such cases.<ref name=":11" /> | ||

=== Anchoring heuristic === | === Anchoring heuristic === | ||

* “...the disposition to concentrate on salient features at the very beginning of the diagnostic process and to insufficiently adjust the initial impression in the light of later information ….. this first impression can be described as a starting value or ‘anchor’. ” | * ''“...the disposition to concentrate on salient features at the very beginning of the diagnostic process and to insufficiently adjust the initial impression in the light of later information ….. this first impression can be described as a starting value or ‘anchor’. ”<ref name=":1" />'' | ||

* “...the clinician fixates on a particular aspect of the patient’s initial presentation, excluding other more relevant clinical | * ''“...the clinician fixates on a particular aspect of the patient’s initial presentation, excluding other more relevant clinical facts.”''<ref name=":5" /> | ||

'''<u>Impact</u>''': It can be an effective heuristic for ensuring efficacy | '''<u>Impact</u>''': It can be an effective heuristic for ensuring efficacy but can negatively influence judgement when that anchor no longer applies to the situation. When it is no longer relevant, it increases the likelihood of incorrect diagnosis and management through premature closure.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

'''<u>Example</u>''': A medical assistant informs a busy doctor of a patient complaining of fatigue and who also seems depressed. The doctor’s thought processes are potentially anchored to the initial label of “depressed patient” and if not deliberately counteracted, the doctor will prescribe antidepressant medication. Should the doctor have inquired about further symptoms, he would have heard of the changes the patient experienced with his skin and hair (unusual in depression) which would have resulted in a more probable diagnosis of hypothyroidism. | '''<u>Example</u>''': A medical assistant informs a busy doctor of a patient complaining of fatigue and who also seems depressed. The doctor’s thought processes are potentially anchored to the initial label of “depressed patient”, and if not deliberately counteracted, the doctor will prescribe antidepressant medication. Should the doctor have inquired about further symptoms, he would have heard of the changes the patient experienced with his skin and hair (unusual in depression), which would have resulted in a more probable diagnosis of hypothyroidism.<ref name=":5" /> | ||

'''<u>Mitigators</u>''': Be aware of the “trap” and avoid early guessing. Use a differential diagnosis toolbox. Delay making a diagnosis until you have a full picture of the patient’s signs and symptoms and your information is complete. Involve the patient in the decision making process. | '''<u>Mitigators</u>''': Be aware of the “trap” and avoid early guessing. Use a differential diagnosis toolbox. Delay making a diagnosis until you have a full picture of the patient’s signs and symptoms and your information is complete. Involve the patient in the decision-making process.<ref name=":11" /><ref name=":12">Whelehan D. [https://members.physio-pedia.com/course_tutor/dale-whelehan/ Heuristics in Clinical Decision Making.] Course. Plus. 2020. </ref> | ||

=== Representativeness heuristic === | === Representativeness heuristic === | ||

* “...the assumption that something that seems similar to other things in a certain category is itself a member of that | * ''“...the assumption that something that seems similar to other things in a certain category is itself a member of that category.”<ref name=":1" />'' | ||

* “...probabilities are evaluated by the degree to which A represents B, that is, by the degree to which A resembles B….[and] not influenced by factors that should affect judgements…prior probability outcomes...sample sizes...chance...predictability...validity...” | * ''“...probabilities are evaluated by the degree to which A represents B, that is, by the degree to which A resembles B….[and] not influenced by factors that should affect judgements…prior probability outcomes...sample sizes...chance...predictability...validity...”<ref name=":15">Blumenthal-Barby JS, Krieger H. [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Heather_Krieger/publication/264990410_Cognitive_Biases_and_Heuristics_in_Medical_Decision_Making_A_Critical_Review_Using_a_Systematic_Search_Strategy/links/552fcd410cf2f2a588aa0387/Cognitive-Biases-and-Heuristics-in-Medical-Decision-Making-A-Critical-Review-Using-a-Systematic-Search-Strategy.pdf Cognitive biases and heuristics in medical decision making: a critical review using a systematic search strategy]. Medical Decision Making. 2015 May;35(4):539-57. DOI:10.1177/0272989X14547740</ref>'' | ||

* “The physician looks for prototypical manifestations of disease (pattern recognition) and fails to consider atypical variants” | * ''“The physician looks for prototypical manifestations of disease (pattern recognition) and fails to consider atypical variants”,<ref name=":13">Ely JW, Graber ML, Croskerry P. [http://www.ajustnhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/checklists-for-diag-errors-Croskerry-2011.pdf Checklists to reduce diagnostic errors]. Academic Medicine. 2011 Mar 1;86(3):307-13. DOI:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820824cd</ref>, i.e. ”if it looks like a duck, quacks like a duck, then it is a duck”.<ref name=":12" />'' | ||

'''<u>Impact</u>''': For experienced practitioners pattern recognition leads to prompt treatment and improved efficacy. It can however also restrain CDM to pattern recognition only which results in | '''<u>Impact</u>''': For experienced practitioners, pattern recognition leads to prompt treatment and improved efficacy. It can, however, also restrain CDM to pattern recognition only, which results in overemphasising particular aspects of the assessment while missing atypical presentations. Less commonly known conditions, therefore, remain undiagnosed and undertreated. This heuristic will also result in misclassification because of overreliance on the prevalence of a condition.<ref name=":0" /> Reliance on the representativeness heuristic may also lead to the overestimation of improbable diagnoses and over-utilisation of resources due to the impact of the “base-rate neglect” effect.<ref name=":1" /> This heuristic is particularly evident in older patients with complex multimorbidity and frailty.<ref name=":3" /> | ||

'''<u>Examples</u>''': A young boy spends the majority of his childhood taking apart electronic equipment (radios, old computers) and reading books about the mechanics behind electronics. As he grows into adulthood, would you expect him to study for a degree in business or | '''<u>Examples</u>''': A young boy spends the majority of his childhood taking apart electronic equipment (radios, old computers) and reading books about the mechanics behind electronics. As he grows into adulthood, would you expect him to study for a degree in business or engineering? Most people expect him to study engineering based on his interests even though statistically, more people will study for a business degree. This is associated with “base rate” neglect/fallacy, where the established prevalence rates are ignored.<ref name=":10" /> Also associated with this is the “halo-effect” bias - “...the tendency for another person’s perceived traits to “spillover” from one area of their personality to another”.<ref name=":6" /> For example, for a patient who is successful in business, works hard and was easy to communicate with, the expectation is also that they are going to follow recommendations, do their exercises and successfully rehabilitate.<ref name=":10" /> | ||

'''<u>Mitigators</u>''': Using a safety check system after the initial diagnosis to shift the thought processes from pattern recognition to analytical processing | '''<u>Mitigators</u>''': Using a safety check system after the initial diagnosis to shift the thought processes from pattern recognition to analytical processing.<ref name=":12" /> Consider further hypotheses for symptoms other than those that readily fit the pattern.<ref name=":13" /> | ||

{{#ev:youtube|https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3IjIVD-KYF4}}<ref>Intermittent Diversion. How heuristics impact our judgement. Published 7 June 2018. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3IjIVD-KYF4 [last accessed 28 January 2021] | {{#ev:youtube|https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3IjIVD-KYF4}}<ref>Intermittent Diversion. How heuristics impact our judgement. Published 7 June 2018. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3IjIVD-KYF4 [last accessed 28 January 2021] | ||

| Line 54: | Line 53: | ||

=== Confirmation bias === | === Confirmation bias === | ||

* “...tendency to look for and notice information that is consistent with our pre-existing expectations and beliefs” | * ''“...tendency to look for and notice information that is consistent with our pre-existing expectations and beliefs”.<ref name=":1" />.'' | ||

* “...tendency to look for evidence “confirming” a diagnosis rather than disconfirming evidence to refute it” | * ''“...tendency to look for evidence “confirming” a diagnosis rather than disconfirming evidence to refute it”.<ref name=":11" />'' | ||

* “Tunnel-vision searching for data to support initial diagnoses while actively ignoring potential data which will reject initial hypotheses.” | * ''“Tunnel-vision searching for data to support initial diagnoses while actively ignoring potential data which will reject initial hypotheses.”<ref name=":0" />'' | ||

'''<u>Impact</u>''': Even though it can support experienced clinicians in resource scarce situations to make quick low risk decisions, it results in premature closure of a diagnosis | '''<u>Impact</u>''': Even though it can support experienced clinicians in resource-scarce situations to make quick, low-risk decisions, it results in premature closure of a diagnosis.<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":16">Trimble M, Hamilton P. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6280203/pdf/clinmed-16-4-343.pdf The thinking doctor: clinical decision making in contemporary medicine]. Clinical Medicine. 2016 Aug;16(4):343.</ref> Clinicians even frame their inquiries to support their beliefs.<ref name=":10" /> It is closely related to the “anchoring” heuristic.<ref name=":0" /> Using confirmation heuristics can also lead to wasted time, effort and resources. At the same time, the correct diagnosis is missed.<ref name=":11" /> The confirmation bias leads to tunnel visioning in diagnosis, which increases the likelihood of paternalistic approaches (the physician knows best) to healthcare which is more system-based, as opposed to the patient-centred care approach.<ref name=":12" /> | ||

'''<u>Example</u>''': When a patient presents with raised white blood cells, a physician immediately suspects the patient has an infection instead of asking himself “I wonder why the white cells are raised, what other findings are there”? | '''<u>Example</u>''': When a patient presents with raised white blood cells, a physician immediately suspects the patient has an infection instead of asking himself “I wonder why the white cells are raised, what other findings are there”?<ref name=":9" /> | ||

'''<u>Mitigators</u>''': Remember that the initial diagnosis is debatable and dependent on both confirming and negating evidence - look at competing hypotheses | '''<u>Mitigators</u>''': Remember that the initial diagnosis is debatable and dependent on both confirming and negating evidence - look at competing hypotheses.<ref name=":11" /> Be open to feedback and open with the patient to engage in shared decision-making. Engage in reflective practice.<ref name=":12" /> | ||

=== Overconfidence heuristic === | === Overconfidence heuristic === | ||

* “When a physician is too sure of their | * ''“When a physician is too sure of their conclusion to entertain other possible differential diagnoses. It may result in decision-making being formulated through opinion or ‘hunch’ as opposed to systematic approaches”.<ref name=":0" />'' | ||

* “...the tendency to overestimate one’s | * ''“...the tendency to overestimate one’s knowledge and accuracy in making decisions. People place too much faith in their opinions instead of carefully gathered evidence.”<ref name=":1" />'' | ||

* “A common tendency to believe we know more than we do.” | * ''“A common tendency to believe we know more than we do.”<ref name=":11" />'' | ||

'''<u>Impact</u>''': This heuristic is driven by the | '''<u>Impact</u>''': This heuristic is driven by the human need to maintain a positive self-image.<ref name=":1" /> It is heavily influenced by personality, and there is an increased risk of the illusion of control within situations. This can lead to overestimating knowledge and understanding and, eventually, incorrect diagnosis and treatment. | ||

'''<u>Example</u>''': A physician assessing a patient presenting with headaches and dizziness over the last few weeks. The physician is convinced the patient has migraine.The patient | '''<u>Example</u>''': A physician assessing a patient presenting with headaches and dizziness over the last few weeks. The physician is convinced the patient has a migraine. The patient thinks they are just “sick”, but the doctor disregards them without considering alternative hypotheses like otitis media or sinusitis.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

'''<u>Mitigators</u>''': These personality-based biases need to be challenged. Cognitive forcing strategies like simulated environments where they can see the consequences of their overconfidence can help clinicians be more aware of their | '''<u>Mitigators</u>''': These personality-based biases need to be challenged. Cognitive forcing strategies like simulated environments where they can see the consequences of their overconfidence can help clinicians be more aware of their limitations and gaps in their knowledge.<ref name=":12" /> | ||

=== Bandwagon heuristic === | === Bandwagon heuristic === | ||

* “...tendency to side with the majority in decision making for fear of standing out. | The bandwagon heuristic defines the action when a person tends to do something primarily because others are doing it. It is a cognitive bias that prevents individuals from following their beliefs. <ref>Lechanoine F, Gangi K. COVID-19: [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7732474/pdf/fpubh-08-613290.pdf Pandemic of Cognitive Biases Impacting Human Behaviors and Decision-Making of Public Health Policies.] Front Public Health. 2020 Nov 24;8:613290. </ref> The bandwagon heuristic is: | ||

* “Group-think and herd effects, often fueled by influential individuals with authority or charisma, may discourage or dismiss dissenting views about the value of an intervention”. | * ''“...tendency to side with the majority in decision making for fear of standing out. <ref name=":0" />'' | ||

'''<u>Impact</u>''': This heuristic is influenced by the work culture of the physiotherapist and encouraged in settings where non-disclosure is more prevalent. Although it can result | * ''“Group-think and herd effects, often fueled by influential individuals with authority or charisma, may discourage or dismiss dissenting views about the value of an intervention”.<ref name=":3" />'' | ||

'''<u>Impact</u>''': This heuristic is influenced by the work culture of the physiotherapist and encouraged in settings where non-disclosure is more prevalent. Although it can result in better harmony and cooperation in teams, it impedes proper decision-making due to the lack of opposing ideas, creativity and feedback on decisions, resulting in missed learning opportunities and sub-optimal care.<ref name=":12" /> | |||

'''<u>Example</u>''': Students mentored by senior members | '''<u>Example</u>''': Students mentored by senior staff members who override individual decision-making. Another example would be a situation with junior doctors on a ward round led by an experienced specialist. The junior doctors would rather concede to the specialist's opinion than raise their opinions/concerns out of fear of repercussions.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

'''<u>Mitigators</u>''': A culture of open disclosure promotes effective communication of team | '''<u>Mitigators</u>''': A culture of open disclosure promotes effective communication of team members and optimises patient care through collaboration.<ref name=":12" /> | ||

=== Commission bias === | === Commission bias === | ||

* “A tendency towards action rather than inaction. Better to be safe than sorry” | Commission bias is an action bias when a person believes that more is better. <ref>Gopal DP, Chetty U, O'Donnell P, Gajria C, Blackadder-Weinstein J. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8004354/pdf/futurehealth-8-1-40.pdf Implicit bias in healthcare: clinical practice, research and decision making.] Future Healthcare Journal. 2021 Mar;8(1):40.</ref> | ||

* “The tendency in the midst of uncertainty to err on the side of action, regardless of the evidence”. | * ''“A tendency towards action rather than inaction. Better to be safe than sorry”.<ref name=":9" />'' | ||

'''<u>Impact</u>''': The commission bias is an important driver of low value, which includes over-investigation and over-treatment | * ''“The tendency in the midst of uncertainty to err on the side of action, regardless of the evidence”.<ref name=":5" />'' | ||

'''<u>Impact</u>''': The commission bias is an important driver of low value, which includes over-investigation and over-treatment.<ref name=":5" /><ref name=":8" /> It can also lead to overconfidence in clinicians who then treat patients in an inappropriate manner which can result in exacerbation of symptoms or cause bodily harm. | |||

'''<u>Example</u>''': In terminal illness, clinicians may continue to administer futile care fueled by the desire to act. | '''<u>Example</u>''': In terminal illness, clinicians may continue to administer futile care fueled by the desire to act.<ref name=":5" /> | ||

'''<u>Mitigators</u>''': Clinical mentoring from experienced clinicians to junior clinicians, safety checklists and decision making aids | '''<u>Mitigators</u>''': Clinical mentoring from experienced clinicians to junior clinicians, safety checklists and decision-making aids.<ref name=":12" /> | ||

=== Omission heuristic === | === Omission heuristic === | ||

* “Tendency to judge actions that lead to harm as worse or less moral than equally harmful non-actions (omissions)”. | * ''“Tendency to judge actions that lead to harm as worse or less moral than equally harmful non-actions (omissions)”.<ref name=":8" />'' | ||

* “A tendency towards inaction grounded in the principle of ‘Do No Harm'”. | * ''“A tendency towards inaction grounded in the principle of ‘Do No Harm'”.<ref name=":11" />'' | ||

'''<u>Impact</u>''': Managing patients too conservatively can lead to delays in treatment and an inadequate response to the clinical symptoms | '''<u>Impact</u>''': Managing patients too conservatively can lead to delays in treatment and an inadequate response to the clinical symptoms.<ref name=":0" /> The clinician would rather attribute the patient’s outcome to the natural progression of a disease than to his/her actions.<ref name=":5" /> | ||

'''<u>Example</u>''': Physicians are more concerned about the potential adverse effects | '''<u>Example</u>''': Physicians are more concerned about the potential adverse effects of treatment than the more pertinent risks of morbidity and mortality associated with the disease.<ref name=":8" /> For example, performing sub-optimal depth compressions during cardiac resuscitation to avoid causing rib fractures.<ref name=":5" /> | ||

'''<u>Mitigators</u>''': Clinical mentoring from experienced clinicians to junior clinicians, safety checklists and decision making aids | |||

'''<u>Mitigators</u>''': Clinical mentoring from experienced clinicians to junior clinicians, safety checklists and decision-making aids.<ref name=":12" /> | |||

=== Aggregate heuristic === | === Aggregate heuristic === | ||

* “...when physicians believe that aggregated data, such as those used to develop practice guidelines, do not apply to individual patients they are treating” | * ''“...when physicians believe that aggregated data, such as those used to develop practice guidelines, do not apply to individual patients they are treating”.<ref name=":0" />'' | ||

'''<u>Impact</u>''': The clinicians believe that aggregated data like those used to develop clinical guidelines, do not apply to them as individual practitioners which results in overriding | '''<u>Impact</u>''': The clinicians believe that aggregated data, like those used to develop clinical guidelines, do not apply to them as individual practitioners, which results in overriding the clinical decision-making rules in favour of the individual judgement.<ref name=":12" /> This approach can lead to the use of “old-school techniques” and non-evidence-based approaches in practice which can result in prolonged ineffective treatment of the patient.<ref name=":12" /> | ||

'''<u>Example</u>''': A patient arriving in emergencies after a car accident with severe bleeding. The patient is also a Jehovah’s Witness and will not consent to a blood transfusion in any circumstance. In lieu of what the surgeon considers to be in the patient’s best interest, the surgeon waits until the patient loses consciousness before deciding to operate and transfuse. | '''<u>Example</u>''': A patient arriving in emergencies after a car accident with severe bleeding. The patient is also a Jehovah’s Witness and will not consent to a blood transfusion in any circumstance. In lieu of what the surgeon considers to be in the patient’s best interest, the surgeon waits until the patient loses consciousness before deciding to operate and transfuse.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

'''<u>Mitigating</u>''': The use of | '''<u>Mitigating</u>''': The use of evidence-based guidelines and research as part of continual professional development.<ref name=":12" /> | ||

=== Status quo bias === | === Status quo bias === | ||

* “A preference for the current state and can be explained with loss aversion. Any change is associated with potential losses and discomfort. As people are loss averse (prospect theory), the losses weigh heavier than the gains.” | * ''“A preference for the current state and can be explained with loss aversion. Any change is associated with potential losses and discomfort. As people are loss averse (prospect theory), the losses weigh heavier than the gains.”<ref name=":8" />'' | ||

* “Having to consider the advantages and disadvantages of ceasing or declining certain interventions is often confronting, resulting in | * ''“Having to consider the advantages and disadvantages of ceasing or declining certain interventions is often confronting, resulting in preference to maintaining the status quo simply.”<ref name=":3" />'' | ||

'''<u>Impact</u>''': Can result in “clinician inertia” when clinicians do not intensify or step down treatments, even when it is indicated. | '''<u>Impact</u>''': Can result in “clinician inertia” when clinicians do not intensify or step down treatments, even when it is indicated.<ref name=":8" /> | ||

'''<u>Example</u>''': Stepping down asthma medication or intensifying treatment for Type 2 diabetes mellitus when indicated. | '''<u>Example</u>''': Stepping down asthma medication or intensifying treatment for Type 2 diabetes mellitus when indicated.<ref name=":8" /> | ||

=== Framing bias === | === Framing bias === | ||

* “...refers to the fact that people’s reaction to a particular choice varies depending on how it is presented, for example, as a loss or as a gain”. | * ''“...refers to the fact that people’s reaction to a particular choice varies depending on how it is presented, for example, as a loss or as a gain”.<ref name=":8" />'' | ||

* “Reacting to a particular choice differently depending on how the information is presented to you” | * ''“Reacting to a particular choice differently depending on how the information is presented to you”.<ref name=":9" />'' | ||

'''<u>Example</u>''': A physician telling a patient that the risk of a brain haemorrhage from oral anticoagulation is 2% is perceived very differently | '''<u>Example</u>''': A physician telling a patient that the risk of a brain haemorrhage from oral anticoagulation is 2% is perceived very differently from informing the patient that there is a 98% chance of not having a brain haemorrhage on treatment.”<ref name=":8" /> | ||

=== Premature closure bias === | === Premature closure bias === | ||

* “Tendency to cease inquiry once a possible solution for a problem is found.” | * ''“Tendency to cease inquiry once a possible solution for a problem is found.”<ref name=":5" />'' | ||

* “The decision making process ends too soon | * ''“The decision-making process ends too soon. The diagnosis is accepted before it has been fully 'verified'”.<ref name=":11" />'' | ||

* “When the diagnosis is made, the thinking stops” | * ''“When the diagnosis is made, the thinking stops”.<ref name=":14" />'' | ||

'''<u>Impact</u>''': Premature closure leads to incomplete assessment of the problem | '''<u>Impact</u>''': Premature closure leads to an incomplete assessment of the problem, resulting in incorrect conclusions.<ref name=":5" /> | ||

=== Affect heuristic === | === Affect heuristic === | ||

* “Representations of objects and events in people’s minds as tagged to varying degrees of | * ''“Representations of objects and events in people’s minds as tagged to varying degrees of effect. People revert to the “affect pool” (all the positive and negative tags associated with the representations) in the process of making judgements”.<ref name=":15" />'' | ||

* “Favourable impressions of an intervention may evoke feelings of attachment and persisting judgements of high benefits, despite clear evidence to the contrary” | * ''“Favourable impressions of an intervention may evoke feelings of attachment and persisting judgements of high benefits, despite clear evidence to the contrary”.<ref name=":3" />'' | ||

=== Sunk cost bias === | === Sunk cost bias === | ||

* “...tendency to continue an | * ''“...tendency to continue an endeavour once an investment in money, effort or time has been made”.<ref name=":15" />'' | ||

* “Clinicians may persist with low value care principally because considerable time, effort, resources and training have already been invested and cannot be forsaken” | * ''“Clinicians may persist with low-value care principally because considerable time, effort, resources and training have already been invested and cannot be forsaken”.<ref name=":3" />'' | ||

'''<u>Impact</u>''': Sum cost fallacy forms part of the confirmation bias. Clinicians justify past investments of time, money and effort through their current investment of time/money and effort and continue to use treatment techniques learnt at school or on a course to justify the time/money/effort spent to confirm their belief that it wasn’t wasted and is not a sunk cost. | '''<u>Impact</u>''': Sum cost fallacy forms part of the confirmation bias. Clinicians justify past investments of time, money and effort through their current investment of time/money and effort and continue to use treatment techniques learnt at school or on a course to justify the time/money/effort spent to confirm their belief that it wasn’t wasted and is not a sunk cost.<ref name=":10" /> | ||

{{#ev:youtube|https://youtu.be/wEwGBIr_RIw}}<ref>Practical Psychology. Twelve Cognitive Biases Explained - How to Think Better and More Logically Removing Bias. Published 30 Dec 2016. Available from https://youtu.be/wEwGBIr_RIw [last accessed 28 January 2021]</ref> | {{#ev:youtube|https://youtu.be/wEwGBIr_RIw}}<ref>Practical Psychology. Twelve Cognitive Biases Explained - How to Think Better and More Logically Removing Bias. Published 30 Dec 2016. Available from https://youtu.be/wEwGBIr_RIw [last accessed 28 January 2021]</ref> | ||

== Cognitive | == Cognitive Debiasing == | ||

The solution to overcoming the biases that influence our decision making lies in a series of cognitive interventional steps called “cognitive debiasing” - “a process of creating awareness of existing bias and intervening to minimise it”. | The solution to overcoming the biases that influence our decision-making lies in a series of cognitive interventional steps called ''“cognitive debiasing”'' - ''“a process of creating awareness of existing bias and intervening to minimise it”''.<ref name=":8" /> Cognitive debiasing is ''“an essential skill in developing sound clinical reasoning”''.<ref name=":17">Croskerry P, Singhal G, Mamede S. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3786644/pdf/bmjqs-2012-001713.pdf Cognitive debiasing 2: impediments to and strategies for change]. BMJ quality & safety. 2013 Oct 1;22(Suppl 2):ii65-72. DOI:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001713</ref> | ||

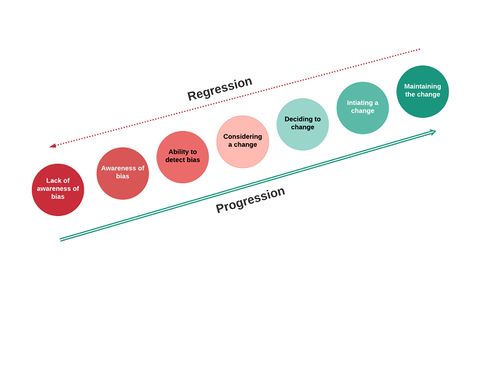

Cognitive | Cognitive debiasing is a process that entails changes which cannot occur in a single event but rather through a series of stages.<ref name=":17" /> See Figure 1. | ||

[[File:Model for changing bias.jpeg|frameless|480x480px]] | [[File:Model for changing bias.jpeg|frameless|480x480px]] | ||

Figure 1: Model of change. Adapted from Croskerry et al | Figure 1: Model of change. Adapted from Croskerry et al.<ref name=":17" /> | ||

=== Cognitive | === Cognitive Debiasing Strategies === | ||

Strategies that could aid in mitigating the impact of cognitive bias have been divided into three main groups.<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":17" /> These groups have considerable overlap and should be considered as a spectrum and not apart from each other.<ref name=":17" /> | |||

'''<u>a. Education Strategies</u>''' | '''<u>a. Education Strategies</u>'''<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":9" /><ref name=":18">Croskerry P. [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Pat_Croskerry/publication/321510386_A_Model_for_Clinical_Decision-Making_in_Medicine/links/5ae70b4c0f7e9b9793c7e527/A-Model-for-Clinical-Decision-Making-in-Medicine.pdf A model for clinical decision-making in medicine]. Medical Science Educator. 2017 Dec 1;27(1):9-13. DOI:10.1007/s40670-017-0499-9</ref> | ||

* Aims to improve clinicians’ abilities to detect the need for debiasing in the future | * Aims to improve clinicians’ abilities to detect the need for debiasing in the future.<ref name=":17" /> | ||

* Involves learning about bias and its risks, | * Involves learning about bias and its risks, identifying it, and providing skills to mitigate it.<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":9" /> | ||

* Elicit self-awareness of own biases in decision making | * Elicit self-awareness of own biases in decision making.<ref name=":12" /> | ||

* Cognitive tutoring systems and simulation training to force clinicians to approach their biases directly | * Cognitive tutoring systems and simulation training to force clinicians to approach their biases directly.<ref name=":8" /> | ||

* Little evidence on the effectiveness of education as a debiasing strategy | * Little evidence on the effectiveness of education as a debiasing strategy.<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":9" /> | ||

'''<u>b. Workplace strategies</u>''' | '''<u>b. Workplace strategies</u>'''<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":17" /> | ||

* Debiasing implemented | * Debiasing is implemented during problem-solving while reasoning about the problem at hand.<ref name=":17" /> | ||

* Includes strategies that | * Includes strategies that rely on the clinician’s cognitive processes. These strategies demand interventions in the settings of practice as well as strategies embedded in the healthcare system to facilitate mitigating cognitive bias. <ref name=":8" /><ref name=":17" /> | ||

* Thorough information gathering | * Thorough information gathering<ref name=":17" /> | ||

* Slowing down strategies - induce slow and deliberate reasoning and a switch to System 2 processing | * Slowing down strategies - induce slow and deliberate reasoning and a switch to System 2 processing, e.g. planned time out in the operating room.<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":9" /><ref name=":17" /> | ||

* Reflective practice and role | * [[Clinical Reflection|Reflective]] practice and role modelling.<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":5" /><ref name=":7" /><ref name=":11" /><ref name=":16" /><ref name=":17" /><ref name=":18" /> | ||

* Metacognition and considering alternatives - think about your | * Metacognition and considering alternatives - think about your thinking and consider, “what else could this be”? <ref name=":9" /><ref name=":16" /><ref name=":17" /><ref name=":18" /><ref>Croskerry P. [https://static1.squarespace.com/static/57b5e6e0ebbd1ad42af1f8b6/t/5d7e9e8f79d8cf7718ca18af/1568579215659/Croskerry+A+Universal+Model+of+Diagnostic+Reasoning.pdf A universal model of diagnostic reasoning.] Academic medicine. 2009 Aug 1;84(8):1022-8. DOI:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ace703</ref> | ||

* Group decision strategy - collaboration and discussion between clinicians about cases | * Group decision strategy - collaboration and discussion between clinicians about cases.<ref name=":5" /><ref name=":11" /><ref name=":17" /> | ||

* Personal accountability and feedback - “thinking out loud” | * Personal accountability and feedback - “thinking out loud”.<ref name=":11" /><ref name=":16" /><ref name=":17" /> | ||

* Decision support systems - including | * Decision support systems - including decision-making aids, differential diagnosis generators, and checklists.<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":1" /><ref name=":5" /><ref name=":8" /><ref name=":9" /><ref name=":13" /><ref name=":17" /> | ||

* Exposure control - not providing the nurse’s notes for the doctor to read before assessing the patient | * Exposure control - not providing the nurse’s notes for the doctor to read before assessing the patient <ref name=":17" /> | ||

* Some evidence exists for the effectiveness of these interventions | * Some evidence exists for the effectiveness of these interventions <ref name=":8" /> | ||

'''<u>c. Forcing functions/Strategies for individual decision makers</u>''' | '''<u>c. Forcing functions/Strategies for individual decision-makers</u>''' <ref name=":8" /><ref name=":17" /> | ||

* Based on cognitive forcing functions - “...the decision maker is forcing conscious intention to information before taking action” | * Based on cognitive forcing functions - “...the decision-maker is forcing conscious intention to information before taking action”<ref name=":8" /> or “...rules that depend on the clinician consciously applying a metacognitive step and cognitively forcing a necessary consideration of alternatives”.<ref name=":17" /> | ||

* Includes deliberate, real-time reflection | * Includes deliberate, real-time reflection<ref name=":8" /> | ||

* Clinical prediction rules | * Clinical prediction rules<ref name=":17" /> | ||

* Rule out Worst-case scenario | * Rule out Worst-case scenario<ref name=":17" /> | ||

* Consider the opposite | * Consider the opposite<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":17" /> | ||

* Checklists | * Checklists<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":13" /><ref name=":17" /> | ||

* | * A structured review of data, templates<ref name=":14" /><ref name=":17" /> | ||

* No evidence in medical context | * No evidence in the medical context<ref name=":8" /> | ||

'''Culture of error disclosure''' | Others have also proposed many other strategies as helpful in overcoming cognitive biases: | ||

* Have an open culture on error making - medical error is inevitable and important to reflect on past activities | * '''Culture of error disclosure'''<ref name=":12" /> | ||

* Mitigates for personality based heuristics | ** Have an open culture on error making - medical error is inevitable, and important to reflect on past activities | ||

** Mitigates for personality-based heuristics | |||

* Human factors training | * '''Human factors training'''<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":5" /><ref name=":9" /> | ||

** Cognitive overload | ** Cognitive overload | ||

** Difficult patients | ** Difficult patients | ||

| Line 190: | Line 192: | ||

** Impact of affect/emotion - include self-awareness check-ins and resilience training | ** Impact of affect/emotion - include self-awareness check-ins and resilience training | ||

* Shared decision making ( | * '''[[Therapeutic Alliance|Shared decision making]]'''<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":3" /><ref>Tousignant-Laflamme Y, Christopher S, Clewley D, Ledbetter L, Cook CJ, Cook CE. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5498795/pdf/yjmt-25-144.pdf Does sharing decision-making result in better health-related outcomes for individuals with painful musculoskeletal disorders? A systematic review]. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. 2017 May 27;25(3):144-50. DOI:10.1080/10669817.2017.1323607</ref><ref>Hoffmann TC, Lewis J, Maher CG. [https://uhra.herts.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/2299/21673/Hoffmann_Lewis_Maher.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=n Shared decision-making should be an integral part of physiotherapy practice.] Physiotherapy. 2020 Jun 1;107:43-9. DOI:10.1016/j.physio.2019.08.012</ref> | ||

** “... a partnership between the clinician and the patient, in which the clinician’s knowledge and preferences (in terms of health care interventions) are evaluated together with the patient’s preferences and needs” | ** “... a partnership between the clinician and the patient, in which the clinician’s knowledge and preferences (in terms of health care interventions) are evaluated together with the patient’s preferences and needs”.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

== Conclusion == | == Conclusion == | ||

The study of heuristics | The study of heuristics raises three questions and has three goals:<ref>Raab M, Gigerenzer G. [https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01672/full The power of simplicity: a fast-and-frugal heuristics approach to performance science]. Frontiers in psychology. 2015 Oct 29;6:1672. DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01672</ref> | ||

# Which | # Which heuristics do clinicians use/rely on? To answer this, we need to analyse the “adaptive toolbox” (collection of heuristics) that clinicians have at their disposal | ||

# When should which heuristic be used, i.e. in which situations is a heuristic more likely to be successful? This goal is prescriptive | # When should which heuristic be used, i.e. in which situations is a heuristic more likely to be successful? This goal is prescriptive and requires the study of the ecological reality of heuristics. | ||

# How can we improve | # How can we improve decision-making? This is an engineering/design goal (“intuitive design”) that strives to design expert systems to improve decision-making. | ||

The general assumption in the literature is that biases and heuristics are “bad” and result in suboptimal decisions. This might occasionally be the case, but heuristics can also be “strengths<nowiki>''</nowiki> that allow clinicians to make quick decisions using simple rules, which is often essential in clinical practice. It is therefore also imperative to understand which cognitive biases and heuristics are detrimental to sound CDM and in which contexts | The general assumption in the literature is that biases and heuristics are “bad” and result in suboptimal decisions. This might occasionally be the case, but heuristics can also be “strengths<nowiki>''</nowiki> that allow clinicians to make quick decisions using simple rules, which is often essential in clinical practice. It is therefore also imperative to understand which cognitive biases and heuristics are detrimental to sound CDM and in which contexts.<ref name=":15" /> Many of the biases evident in clinicians are recognisable and correctable, which underlie the concept of learning and refining clinical practice.<ref name=":2" /> | ||

The general goal should | |||

The general goal should be to formalise and understand heuristics to teach their use more effectively. This will also result in less variation in practice and more efficient health care.<ref>Marewski JN, Gigerenzer G. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3341653/pdf/DialoguesClinNeurosci-14-77.pdf Heuristic decision making in medicine]. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience. 2012 Mar;14(1):77. </ref> | |||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<div class="col-md-6"> {{#ev:youtube|https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LzkmabM_Rxw}}<div class="text-right"><ref>Hege I. Cognitive Errors and Biases in Clinical Reasoning. Published 9 Jan 2017. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LzkmabM_Rxw [last accessed 28 January 2021]</ref></div></div> | <div class="col-md-6"> {{#ev:youtube|https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LzkmabM_Rxw|250}}<div class="text-right"><ref>Hege I. Cognitive Errors and Biases in Clinical Reasoning. Published 9 Jan 2017. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LzkmabM_Rxw [last accessed 28 January 2021]</ref></div></div> | ||

<div class="col-md-6"> {{#ev:youtube|https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OXcGciywtgM}}<div class="text-right"><ref>Marjorie Stiegler MD. Understanding and Preventing Cognitive Errors in Healthcare. Published 24 Nov 2014. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OXcGciywtgM [last accessed 28 January 2021]</ref></div></div> | <div class="col-md-6"> {{#ev:youtube|https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OXcGciywtgM|250}}<div class="text-right"><ref>Marjorie Stiegler MD. Understanding and Preventing Cognitive Errors in Healthcare. Published 24 Nov 2014. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OXcGciywtgM [last accessed 28 January 2021]</ref></div></div> | ||

</div> | |||

== Resources == | == Resources == | ||

* | *[https://www.zacharywalston.com/podcast/episode/4ad23911/how-do-we-make-clinical-decisions How do we make clinical decisions] | ||

* | *[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ooWA4tM_gUs How Medical Research Gets it wrong] (Medical Bias Part 1) by Medlife Crisis | ||

*[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8wlq7-v3-bc Why Doctors Make Mistakes] (Medical Bias Part 2) by Medlife Crisis | |||

'''Related articles''' | |||

* [[Clinical Reflection|Clinical Reflection - Physiopedia]] | |||

* [[Evidence Based Practice(EBP) in Physiotherapy|Evidence Based Practice (EBP) in Physiotherapy - Physiopedia]] | |||

* [[British Columbia Physical Therapy Knowledge Broker Project|Decision Making Aids - Physiopedia]] | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Decision Making]] | |||

[[Category:Course Pages]] | |||

[[Category:Plus Content]] | |||

[[Category:Professional Skills]] | |||

Latest revision as of 23:58, 26 December 2022

Original Editor - Merinda Rodseth

Top Contributors - Merinda Rodseth, Kim Jackson, Tarina van der Stockt, Ewa Jaraczewska and Jess Bell

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Clinicians make decisions daily which impact the lives of others.[1] They are forced to continually make decisions despite the uncertainty that often taints the situation and any cognitive limitations.[2] To achieve this, clinicians mostly rely on heuristics - simple cognitive shortcuts influenced by our cognitive biases - which assists in clinical decision making (CDM).[1][2][3][4] The advantage of relying on heuristics is that decisions can be made quickly and are mostly accurate and efficient. [2][4][5] But there is also a disadvantage: they often lead to systematic cognitive errors.[2][3][5] Our cognitive errors are also known as “cognitive biases”.[3]

What is Cognitive Bias?[edit | edit source]

Bias is inherent to human judgement[3] and can be defined as:

- “the psychological tendency to make a decision based on incomplete information and subjective factors rather than empirical evidence”.[6]

- “predictable deviations from rationality”.[3]

Cognitive biases are evident in CDM when information is inappropriately processed and/or overly focused upon (while ignoring other and more relevant information). This process happens subconsciously with the user unaware of its influence and mostly happens during automatic System 1 processing using heuristics.[7] A systematic review done by Saposnik et al [8] found that cognitive biases may be associated with diagnostic inaccuracies, but limited information is currently available on the impact on evidence-based care.[8]

Heuristics and Biases in Medical Practice[edit | edit source]

Availability heuristic[edit | edit source]

- “Tendency to make likelihood predictions based on what can easily be remembered.”[9]

- “More recent and readily available answers and solutions are preferentially favoured because of ease of recall and incorrectly perceived importance.”[10]

- “Tendency to overestimate the frequency of things if they are more easily brought to mind. Things are judged to be more frequently occurring if they come to mind easily, probably because they are remembered without difficulty or because they were recently encountered.”[2]

- “Emotionally charged and vivid case studies that come easily to mind (i.e. are available) can unduly inflate estimates of the likelihood of the same scenario being repeated.”[4]

It is important to note that most available evidence is not necessarily the most relevant, and events that are easily remembered do not necessarily occur more frequently.[2][9] This heuristic is also closely related to the “Base-rate neglect” fallacy:

- “... when the underlying incident rates of conditions or population-based knowledge are ignored as if they do not apply to the patient in question.”[10]

- “...tendency to ignore the true prevalence of a disease, either inflating or reducing its base rate...”[11]

Impact: Base rate neglect overrides the knowledge of the prevalence of disease/conditions, and unnecessary tests are ordered regardless of very low probability.[10] It can lead to distorted hypothesis generation and thereby result in under-or overestimation of certain diagnoses. It can also heavily influence the types of tests ordered, treatments given and information provided to patients (based on what comes to mind).[1][2][12]

Examples: A physiotherapist who recently attended a course on manipulation will be more inclined to use manipulation in the days following the course.[12] This is also evident if asked for the name of the capital of Australia. Most people will quickly answer with “Sydney”, whereas Canberra is Australia's capital. As Sydney is generally more well-known, it comes to mind first.[13] Conditions/diseases that are less frequently encountered will be less “available” in the clinician’s mind and, therefore, less likely to be diagnosed.[2][14]

Mitigators: Look for refuting evidence in the history and examination that may be less obvious. Ensure a comprehensive knowledge of the differential diagnosis. Be attentive to atypical signs and symptoms indicative of more severe pathology and consult with colleagues on such cases.[14]

Anchoring heuristic[edit | edit source]

- “...the disposition to concentrate on salient features at the very beginning of the diagnostic process and to insufficiently adjust the initial impression in the light of later information ….. this first impression can be described as a starting value or ‘anchor’. ”[2]

- “...the clinician fixates on a particular aspect of the patient’s initial presentation, excluding other more relevant clinical facts.”[6]

Impact: It can be an effective heuristic for ensuring efficacy but can negatively influence judgement when that anchor no longer applies to the situation. When it is no longer relevant, it increases the likelihood of incorrect diagnosis and management through premature closure.[1]

Example: A medical assistant informs a busy doctor of a patient complaining of fatigue and who also seems depressed. The doctor’s thought processes are potentially anchored to the initial label of “depressed patient”, and if not deliberately counteracted, the doctor will prescribe antidepressant medication. Should the doctor have inquired about further symptoms, he would have heard of the changes the patient experienced with his skin and hair (unusual in depression), which would have resulted in a more probable diagnosis of hypothyroidism.[6]

Mitigators: Be aware of the “trap” and avoid early guessing. Use a differential diagnosis toolbox. Delay making a diagnosis until you have a full picture of the patient’s signs and symptoms and your information is complete. Involve the patient in the decision-making process.[14][15]

Representativeness heuristic[edit | edit source]

- “...the assumption that something that seems similar to other things in a certain category is itself a member of that category.”[2]

- “...probabilities are evaluated by the degree to which A represents B, that is, by the degree to which A resembles B….[and] not influenced by factors that should affect judgements…prior probability outcomes...sample sizes...chance...predictability...validity...”[16]

- “The physician looks for prototypical manifestations of disease (pattern recognition) and fails to consider atypical variants”,[17], i.e. ”if it looks like a duck, quacks like a duck, then it is a duck”.[15]

Impact: For experienced practitioners, pattern recognition leads to prompt treatment and improved efficacy. It can, however, also restrain CDM to pattern recognition only, which results in overemphasising particular aspects of the assessment while missing atypical presentations. Less commonly known conditions, therefore, remain undiagnosed and undertreated. This heuristic will also result in misclassification because of overreliance on the prevalence of a condition.[1] Reliance on the representativeness heuristic may also lead to the overestimation of improbable diagnoses and over-utilisation of resources due to the impact of the “base-rate neglect” effect.[2] This heuristic is particularly evident in older patients with complex multimorbidity and frailty.[4]

Examples: A young boy spends the majority of his childhood taking apart electronic equipment (radios, old computers) and reading books about the mechanics behind electronics. As he grows into adulthood, would you expect him to study for a degree in business or engineering? Most people expect him to study engineering based on his interests even though statistically, more people will study for a business degree. This is associated with “base rate” neglect/fallacy, where the established prevalence rates are ignored.[12] Also associated with this is the “halo-effect” bias - “...the tendency for another person’s perceived traits to “spillover” from one area of their personality to another”.[7] For example, for a patient who is successful in business, works hard and was easy to communicate with, the expectation is also that they are going to follow recommendations, do their exercises and successfully rehabilitate.[12]

Mitigators: Using a safety check system after the initial diagnosis to shift the thought processes from pattern recognition to analytical processing.[15] Consider further hypotheses for symptoms other than those that readily fit the pattern.[17]

Confirmation bias[edit | edit source]

- “...tendency to look for and notice information that is consistent with our pre-existing expectations and beliefs”.[2].

- “...tendency to look for evidence “confirming” a diagnosis rather than disconfirming evidence to refute it”.[14]

- “Tunnel-vision searching for data to support initial diagnoses while actively ignoring potential data which will reject initial hypotheses.”[1]

Impact: Even though it can support experienced clinicians in resource-scarce situations to make quick, low-risk decisions, it results in premature closure of a diagnosis.[1][19] Clinicians even frame their inquiries to support their beliefs.[12] It is closely related to the “anchoring” heuristic.[1] Using confirmation heuristics can also lead to wasted time, effort and resources. At the same time, the correct diagnosis is missed.[14] The confirmation bias leads to tunnel visioning in diagnosis, which increases the likelihood of paternalistic approaches (the physician knows best) to healthcare which is more system-based, as opposed to the patient-centred care approach.[15]

Example: When a patient presents with raised white blood cells, a physician immediately suspects the patient has an infection instead of asking himself “I wonder why the white cells are raised, what other findings are there”?[10]

Mitigators: Remember that the initial diagnosis is debatable and dependent on both confirming and negating evidence - look at competing hypotheses.[14] Be open to feedback and open with the patient to engage in shared decision-making. Engage in reflective practice.[15]

Overconfidence heuristic[edit | edit source]

- “When a physician is too sure of their conclusion to entertain other possible differential diagnoses. It may result in decision-making being formulated through opinion or ‘hunch’ as opposed to systematic approaches”.[1]

- “...the tendency to overestimate one’s knowledge and accuracy in making decisions. People place too much faith in their opinions instead of carefully gathered evidence.”[2]

- “A common tendency to believe we know more than we do.”[14]

Impact: This heuristic is driven by the human need to maintain a positive self-image.[2] It is heavily influenced by personality, and there is an increased risk of the illusion of control within situations. This can lead to overestimating knowledge and understanding and, eventually, incorrect diagnosis and treatment.

Example: A physician assessing a patient presenting with headaches and dizziness over the last few weeks. The physician is convinced the patient has a migraine. The patient thinks they are just “sick”, but the doctor disregards them without considering alternative hypotheses like otitis media or sinusitis.[1]

Mitigators: These personality-based biases need to be challenged. Cognitive forcing strategies like simulated environments where they can see the consequences of their overconfidence can help clinicians be more aware of their limitations and gaps in their knowledge.[15]

Bandwagon heuristic[edit | edit source]

The bandwagon heuristic defines the action when a person tends to do something primarily because others are doing it. It is a cognitive bias that prevents individuals from following their beliefs. [20] The bandwagon heuristic is:

- “...tendency to side with the majority in decision making for fear of standing out. [1]

- “Group-think and herd effects, often fueled by influential individuals with authority or charisma, may discourage or dismiss dissenting views about the value of an intervention”.[4]

Impact: This heuristic is influenced by the work culture of the physiotherapist and encouraged in settings where non-disclosure is more prevalent. Although it can result in better harmony and cooperation in teams, it impedes proper decision-making due to the lack of opposing ideas, creativity and feedback on decisions, resulting in missed learning opportunities and sub-optimal care.[15]

Example: Students mentored by senior staff members who override individual decision-making. Another example would be a situation with junior doctors on a ward round led by an experienced specialist. The junior doctors would rather concede to the specialist's opinion than raise their opinions/concerns out of fear of repercussions.[1]

Mitigators: A culture of open disclosure promotes effective communication of team members and optimises patient care through collaboration.[15]

Commission bias[edit | edit source]

Commission bias is an action bias when a person believes that more is better. [21]

- “A tendency towards action rather than inaction. Better to be safe than sorry”.[10]

- “The tendency in the midst of uncertainty to err on the side of action, regardless of the evidence”.[6]

Impact: The commission bias is an important driver of low value, which includes over-investigation and over-treatment.[6][9] It can also lead to overconfidence in clinicians who then treat patients in an inappropriate manner which can result in exacerbation of symptoms or cause bodily harm.

Example: In terminal illness, clinicians may continue to administer futile care fueled by the desire to act.[6]

Mitigators: Clinical mentoring from experienced clinicians to junior clinicians, safety checklists and decision-making aids.[15]

Omission heuristic[edit | edit source]

- “Tendency to judge actions that lead to harm as worse or less moral than equally harmful non-actions (omissions)”.[9]

- “A tendency towards inaction grounded in the principle of ‘Do No Harm'”.[14]

Impact: Managing patients too conservatively can lead to delays in treatment and an inadequate response to the clinical symptoms.[1] The clinician would rather attribute the patient’s outcome to the natural progression of a disease than to his/her actions.[6]

Example: Physicians are more concerned about the potential adverse effects of treatment than the more pertinent risks of morbidity and mortality associated with the disease.[9] For example, performing sub-optimal depth compressions during cardiac resuscitation to avoid causing rib fractures.[6]

Mitigators: Clinical mentoring from experienced clinicians to junior clinicians, safety checklists and decision-making aids.[15]

Aggregate heuristic[edit | edit source]

- “...when physicians believe that aggregated data, such as those used to develop practice guidelines, do not apply to individual patients they are treating”.[1]

Impact: The clinicians believe that aggregated data, like those used to develop clinical guidelines, do not apply to them as individual practitioners, which results in overriding the clinical decision-making rules in favour of the individual judgement.[15] This approach can lead to the use of “old-school techniques” and non-evidence-based approaches in practice which can result in prolonged ineffective treatment of the patient.[15]

Example: A patient arriving in emergencies after a car accident with severe bleeding. The patient is also a Jehovah’s Witness and will not consent to a blood transfusion in any circumstance. In lieu of what the surgeon considers to be in the patient’s best interest, the surgeon waits until the patient loses consciousness before deciding to operate and transfuse.[1]

Mitigating: The use of evidence-based guidelines and research as part of continual professional development.[15]

Status quo bias[edit | edit source]

- “A preference for the current state and can be explained with loss aversion. Any change is associated with potential losses and discomfort. As people are loss averse (prospect theory), the losses weigh heavier than the gains.”[9]

- “Having to consider the advantages and disadvantages of ceasing or declining certain interventions is often confronting, resulting in preference to maintaining the status quo simply.”[4]

Impact: Can result in “clinician inertia” when clinicians do not intensify or step down treatments, even when it is indicated.[9]

Example: Stepping down asthma medication or intensifying treatment for Type 2 diabetes mellitus when indicated.[9]

Framing bias[edit | edit source]

- “...refers to the fact that people’s reaction to a particular choice varies depending on how it is presented, for example, as a loss or as a gain”.[9]

- “Reacting to a particular choice differently depending on how the information is presented to you”.[10]

Example: A physician telling a patient that the risk of a brain haemorrhage from oral anticoagulation is 2% is perceived very differently from informing the patient that there is a 98% chance of not having a brain haemorrhage on treatment.”[9]

Premature closure bias[edit | edit source]

- “Tendency to cease inquiry once a possible solution for a problem is found.”[6]

- “The decision-making process ends too soon. The diagnosis is accepted before it has been fully 'verified'”.[14]

- “When the diagnosis is made, the thinking stops”.[11]

Impact: Premature closure leads to an incomplete assessment of the problem, resulting in incorrect conclusions.[6]

Affect heuristic[edit | edit source]

- “Representations of objects and events in people’s minds as tagged to varying degrees of effect. People revert to the “affect pool” (all the positive and negative tags associated with the representations) in the process of making judgements”.[16]

- “Favourable impressions of an intervention may evoke feelings of attachment and persisting judgements of high benefits, despite clear evidence to the contrary”.[4]

Sunk cost bias[edit | edit source]

- “...tendency to continue an endeavour once an investment in money, effort or time has been made”.[16]

- “Clinicians may persist with low-value care principally because considerable time, effort, resources and training have already been invested and cannot be forsaken”.[4]

Impact: Sum cost fallacy forms part of the confirmation bias. Clinicians justify past investments of time, money and effort through their current investment of time/money and effort and continue to use treatment techniques learnt at school or on a course to justify the time/money/effort spent to confirm their belief that it wasn’t wasted and is not a sunk cost.[12]

Cognitive Debiasing[edit | edit source]

The solution to overcoming the biases that influence our decision-making lies in a series of cognitive interventional steps called “cognitive debiasing” - “a process of creating awareness of existing bias and intervening to minimise it”.[9] Cognitive debiasing is “an essential skill in developing sound clinical reasoning”.[23]

Cognitive debiasing is a process that entails changes which cannot occur in a single event but rather through a series of stages.[23] See Figure 1.

Figure 1: Model of change. Adapted from Croskerry et al.[23]

Cognitive Debiasing Strategies[edit | edit source]

Strategies that could aid in mitigating the impact of cognitive bias have been divided into three main groups.[9][23] These groups have considerable overlap and should be considered as a spectrum and not apart from each other.[23]

a. Education Strategies[9][10][24]

- Aims to improve clinicians’ abilities to detect the need for debiasing in the future.[23]

- Involves learning about bias and its risks, identifying it, and providing skills to mitigate it.[9][10]

- Elicit self-awareness of own biases in decision making.[15]

- Cognitive tutoring systems and simulation training to force clinicians to approach their biases directly.[9]

- Little evidence on the effectiveness of education as a debiasing strategy.[9][10]

b. Workplace strategies[9][23]

- Debiasing is implemented during problem-solving while reasoning about the problem at hand.[23]

- Includes strategies that rely on the clinician’s cognitive processes. These strategies demand interventions in the settings of practice as well as strategies embedded in the healthcare system to facilitate mitigating cognitive bias. [9][23]

- Thorough information gathering[23]

- Slowing down strategies - induce slow and deliberate reasoning and a switch to System 2 processing, e.g. planned time out in the operating room.[9][10][23]

- Reflective practice and role modelling.[4][6][8][14][19][23][24]

- Metacognition and considering alternatives - think about your thinking and consider, “what else could this be”? [10][19][23][24][25]

- Group decision strategy - collaboration and discussion between clinicians about cases.[6][14][23]

- Personal accountability and feedback - “thinking out loud”.[14][19][23]

- Decision support systems - including decision-making aids, differential diagnosis generators, and checklists.[1][2][6][9][10][17][23]

- Exposure control - not providing the nurse’s notes for the doctor to read before assessing the patient [23]

- Some evidence exists for the effectiveness of these interventions [9]

c. Forcing functions/Strategies for individual decision-makers [9][23]

- Based on cognitive forcing functions - “...the decision-maker is forcing conscious intention to information before taking action”[9] or “...rules that depend on the clinician consciously applying a metacognitive step and cognitively forcing a necessary consideration of alternatives”.[23]

- Includes deliberate, real-time reflection[9]

- Clinical prediction rules[23]

- Rule out Worst-case scenario[23]

- Consider the opposite[9][23]

- Checklists[9][17][23]

- A structured review of data, templates[11][23]

- No evidence in the medical context[9]

Others have also proposed many other strategies as helpful in overcoming cognitive biases:

- Culture of error disclosure[15]

- Have an open culture on error making - medical error is inevitable, and important to reflect on past activities

- Mitigates for personality-based heuristics

- Human factors training[1][6][10]

- Cognitive overload

- Difficult patients

- Sleep deprivation

- Consider fatigue

- Impact of affect/emotion - include self-awareness check-ins and resilience training

- Shared decision making[2][4][26][27]

- “... a partnership between the clinician and the patient, in which the clinician’s knowledge and preferences (in terms of health care interventions) are evaluated together with the patient’s preferences and needs”.[2]

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

The study of heuristics raises three questions and has three goals:[28]

- Which heuristics do clinicians use/rely on? To answer this, we need to analyse the “adaptive toolbox” (collection of heuristics) that clinicians have at their disposal

- When should which heuristic be used, i.e. in which situations is a heuristic more likely to be successful? This goal is prescriptive and requires the study of the ecological reality of heuristics.

- How can we improve decision-making? This is an engineering/design goal (“intuitive design”) that strives to design expert systems to improve decision-making.

The general assumption in the literature is that biases and heuristics are “bad” and result in suboptimal decisions. This might occasionally be the case, but heuristics can also be “strengths'' that allow clinicians to make quick decisions using simple rules, which is often essential in clinical practice. It is therefore also imperative to understand which cognitive biases and heuristics are detrimental to sound CDM and in which contexts.[16] Many of the biases evident in clinicians are recognisable and correctable, which underlie the concept of learning and refining clinical practice.[3]

The general goal should be to formalise and understand heuristics to teach their use more effectively. This will also result in less variation in practice and more efficient health care.[29]

Resources[edit | edit source]

- How do we make clinical decisions

- How Medical Research Gets it wrong (Medical Bias Part 1) by Medlife Crisis

- Why Doctors Make Mistakes (Medical Bias Part 2) by Medlife Crisis

Related articles

- Clinical Reflection - Physiopedia

- Evidence Based Practice (EBP) in Physiotherapy - Physiopedia

- Decision Making Aids - Physiopedia

References[edit | edit source]