Multidimensional Nature of Pain: Difference between revisions

(replace wrong ampersand with single one) |

Kim Jackson (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "PlusContent" to "Plus Content") |

||

| (42 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | <div class="editorbox"> | ||

'''Original Editor '''- [[User:Alberto Bertaggia|Alberto Bertaggia]]. | '''Original Editor '''- [[User:Alberto Bertaggia|Alberto Bertaggia]]. | ||

| Line 6: | Line 7: | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

A definition of pain is provided by the International association for the Study of Pain (IASP) as follows<ref name="IASP Pain">IASP | A definition of pain is provided by the International association for the Study of Pain (IASP) as follows:<ref name="IASP Pain">International Association for the Study of Pain. IASP Terminology. Available from: https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1698. [Accessed 19 July 2020]</ref><br> | ||

<blockquote>''' | <blockquote>'''An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage'''<br> </blockquote> | ||

Pain is always '''subjective''' and everyone learns the use of this word through experiences related to injury in early life.<br> | Pain is always '''subjective''' and everyone learns the use of this word through experiences related to injury in early life.<br> | ||

Pain is '''a sensation in a part or parts of the body.''' It can vary in intensity, quality, duration and pain can refer to other parts of the body'''.''' Pain is usually an '''unpleasant sensation and therefore it also has an emotional aspect'''. It is strongly linked to suffering.<ref name="Woolf 2004" /> | |||

Even in the absence of tissue damage or any likely pathophysiological cause, people still report pain. This could happen for psychological reasons. In these cases, it is challenging to distinguish whether someone's experience of pain arises from damaged tissue or not, as it can only be based upon the subjective report of such experience.<ref name="Merskey 1994">Merskey H (ed.), Bogduk N (ed.). ''[https://s3.amazonaws.com/rdcms-iasp/files/production/public/Content/ContentFolders/Publications2/FreeBooks/Classification-of-Chronic-Pain.pdf Classification of chronic pain; Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms]''. 2nd ed. Seattle: IASP Press; 1994 Available from: https://s3.amazonaws.com/rdcms-iasp/files/production/public/Content/ContentFolders/Publications2/FreeBooks/Classification-of-Chronic-Pain.pdf [Accessed on 10 May 2019]</ref><br> | |||

== | In the following video, Karen D. Davis tries to explain why some people react to the same painful stimulus in different ways.<br> <br>{{#ev:youtube|I7wfDenj6CQ}} <br><ref>TED-Ed. How does your brain respond to pain? - Karen D. Davis Available from | ||

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I7wfDenj6CQ&feature=emb_logo</ref> | |||

=== | ==The Process of Feeling Pain== | ||

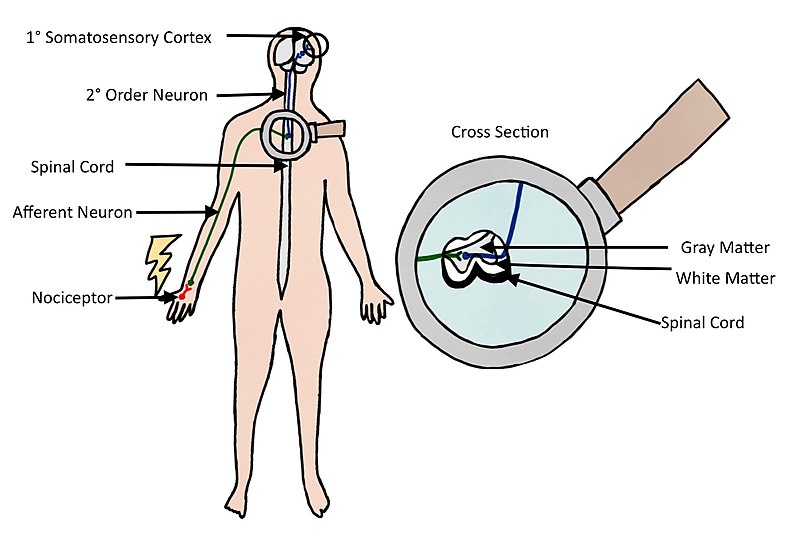

Pain is a physiological protective system. It is essential to warn, detect, and minimize contact with damaging stimuli.<ref name="Woolf 2010">Woolf CJ. [https://www.jci.org/articles/view/45178/pdf What is this thing called pain?.] ''The Journal of clinical investigation''. 2010 Nov 1;120(11):3742-4. Available from: https://www.jci.org/articles/view/45178/pdf [Accessed on 10 May 2019]</ref> Nerve endings and sensory receptors in the skin and tissues detect sensory stimuli. This can be thermal, mechanical or chemical stimuli (heat, cold, pressure, etc.). [https://physio-pedia.com/Nociception Nociceptors] (from the Latin word ''nocere'' that means ''"''to hurt") are sensory receptors that respond to damaging or potentially damaging stimuli. With the stimulation of a nociceptor, a noxious stimulus is converted into electrical activity in the peripheral terminals of nociceptor sensory fibres. This is called transduction. The stimulus is carried to the spinal cord (central nervous system) through a process called conduction. The nociceptive nerve fibres terminate and the synaptic transfer and modulation of input from one neuron to another take place. This is called transmission. The neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord transfer nociceptive input to the brainstem, hypothalamus, thalamus and brain cortex. In the brain perception of the experience occurs. This is a subjective process. Only then does the brain create pain as output after processing the stimuli. It is important to underline that activity induced in the nociceptive pathways by a noxious stimulus does not always lead to pain. Nociceptors can be stimulated by potentially damaging stimuli as well as actual damaging stimuli. Only when the brain has processed the stimulus, will it lead to a response of pain or not. Pain is always the output of a widely distributed neural network in the brain rather than one coming directly by sensory input evoked by injury, inflammation or other pathology<ref name="Dubin 2010">Dubin AE, Patapoutian A. [https://www.jci.org/articles/view/42843/pdf Nociceptors: the sensors of the pain pathway]. ''The Journal of clinical investigation''. 2010 Nov 1;120(11):3760-72. Available from: https://www.jci.org/articles/view/42843/pdf [Accessed on 10 May 2019]</ref>. | |||

[[File:Nociception Illustration.jpg|center|frame|638x638px|[https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nociception_Illustration.jpg Nociception]]] | |||

<br> | |||

== Pain Classification == | |||

Based on the works of Woolf<ref name="Woolf 2010" />, this is a useful way of classifying pain: | |||

* ''Nociceptive pain''. This kind of pain is concerned with the sensing of noxious stimuli. It is a signal of impending or actual tissue damage and is a high-threshold pain only activated in the presence of intense stimuli. It has a protective role requiring immediate attention and responses (i.e. withdrawal reflex). For example, touching something too hot, cold or sharp | |||

* ''Inflammatory pain''. This second kind of pain is important to promote healing and protection of injured tissues. It increases sensory sensitivity through pain hypersensitivity and tenderness. Thus normally innocuous stimuli now elicit pain. It creates an environment which suggests avoidance of movement, contact and stress of the injured body parts. This, in turn, assists in the healing of the injured body part. Inflammatory pain is caused by activation of the immune system that causes inflammation after tissue injury or infection. This type of pain can be seen as a protective mechanism, However, it still needs to be reduced in patients with ongoing inflammation, as with rheumatoid arthritis or in cases of severe or extensive injury. | |||

* ''Pathological pain''. This type of pain is not protective, but rather maladaptive. It is not connected to tissue damage but results from abnormal functioning of the nervous system. To note, this is a low-threshold pain. Pathological pain can occur after damage to the nervous system or even when there is no damage or inflammation, It is largely the consequence of amplified sensory signals in the central nervous system. Conditions that cause this type of pain include fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, tension-type headache, temporomandibular joint disease etc. Usually, the pain is substantial without any noxious stimulus and minimal or even no peripheral inflammation. | |||

'''Acute pain''' is caused by noxious stimuli and is mediated by nociception. It has an early onset and serves to prevent tissue damage. This is why this type of pain is defined as adaptive, it helps to survive and to heal<ref name="Woolf 2004">Woolf CJ. [http://www.smbs.buffalo.edu/acb/neuro/readings/SensitizMolecMech.pdf Pain: moving from symptom control toward mechanism-specific pharmacologic management.] ''Ann Intern Med''. 2004;140:441-51. Available from: http://www.smbs.buffalo.edu/acb/neuro/readings/SensitizMolecMech.pdf [Accessed 12 May 2019] </ref> | |||

'''Chronic pain''' is pain continuing beyond 3 months, or after healing is complete<ref name="Merskey 1994" />. It may arise as a consequence of tissue damage or inflammation or have no identified cause. Chronic pain is a complex condition embracing physical, social and psychological factors, consequently leading to disability, loss of independence and poor quality of life.<ref name="Breivik 2006">Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. [http://www.nascholingnoord.nl/presentaties/2012_02_02_Breivik_et_al___Survey_of_chronic_pain_in_Europe.pdf Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment]. ''European journal of pain.'' 2006 May;10(4):287–333. Available from: http://www.nascholingnoord.nl/presentaties/2012_02_02_Breivik_et_al___Survey_of_chronic_pain_in_Europe.pdf [Accessed on 12 May 2019] </ref> | |||

=== | == The Biopsychosocial Model of Pain == | ||

In the past, psychological and physiological (or pathophysiological) factors were considered as separate components in a dualistic point of view. Later, the recognition that psychosocial factors, such as emotional stress and fear, could impact the reporting of symptoms, medical disorders, and response to treatment lead to the development of the biopsychosocial model of pain<ref name="Gatchel 2007">Gatchel RJ, Peng YB, Peters ML, Fuchs PN, Turk DC. [https://rc.library.uta.edu/uta-ir/bitstream/handle/10106/5000/BIOPSYCHO2006-0750-R-Final-single%20701.pdf?sequence=1 The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific advances and future directions]. ''Psychological Bulletin''. 2007 Jul;133(4):581. Available from: https://rc.library.uta.edu/uta-ir/bitstream/handle/10106/5000/BIOPSYCHO2006-0750-R-Final-single%20701.pdf?sequence=1 [Accessed on 12 May 2019]</ref>.<br> | |||

The ''bio ''part represents the pathophysiology of the disease or the mechanism of injury, and the relative nociception processes, it considers the physiological aspects of the pain experience.<br> | |||

The ''[[Psychological Basis of Pain|psychosocial]]'' part involves both emotion (the more immediate reaction to nociception and is more midbrain based) and cognition (which attach meaning to the emotional experience). These could trigger additional emotional reactions and thereby amplify the experience of pain, thus perpetuating a vicious circle of nociception, pain, distress, and disability.<ref name="Gatchel 2007" /><br> | |||

It could be said that psychological factors, such as fear and anxiety, play an important role in the development of chronic pain. <ref name="Gatchel 2007" /> | |||

== | == Psychological Factors in Pain == | ||

=== Anxiety === | |||

Health anxious individuals form dysfunctional assumptions and beliefs about pain and other symptoms. This can be disease based and based on past experiences. They will have a tendency to misinterpret somatic information as catastrophic and personally threatening. Some studies report an increase in pain correlated with increased levels of anxiety.<ref name="Moseley 2007">Moseley GL. [https://cdn.bodyinmind.org/wp-content/uploads/Moseley-2007-PTR-conceptualisation1.pdf Reconceptualising pain according to modern pain science.] ''Physical therapy reviews''. 2007 Sep 1;12(3):169-78. Available from: https://cdn.bodyinmind.org/wp-content/uploads/Moseley-2007-PTR-conceptualisation1.pdf [Accessed on 12 May 2019]</ref> Clinically, anxiety can compromise treatments as practitioners can expect to see catastrophization play a big role in these patients' report and they could report greater pain during activities. Thus, there is a need to target attentional focus and interpretation of sensations among health anxious clients. <br> | |||

=== Depression === | |||

= | There is strong evidence of established comorbidity of pain and depression.<ref name="Blair 2003">Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. [https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/216320 Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review]. ''Archives of internal medicine''. 2003 Nov 10;163(20):2433-45. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/216320 [Accessed on 12 May 2019]</ref> Furthermore, when patients with pain have comorbid depression, they could experience greater pain, have a worse prognosis, and more functional disability. Pain and depression are linked by neurobiological, cognitive, affective and behavioural factors. Thus, the optimal treatment approach for comorbid pain and depression should simultaneously address both physical and psychological symptoms.<br> | ||

=== | === Expectation === | ||

When an individual expects to experience pain, the perceived pain may vary based upon the types of cues received (i.e. a cue may indicate a more intense or damaging stimulus, then more intense pain is perceived and vice versa). Cues of an impending treatment could also decrease pain, for example, the process of taking an analgesic, usually decreases pain.<ref name="Moseley 2007" /> Thus, expectation is thought to play a big role in the placebo effect.<br> | |||

=== Attention and Distraction === | |||

There is strong evidence that attention (and distraction) is highly effective in modulating the pain experience and demonstrate how cognitive processes can interfere with pain perception. When a person is distracted with a cognitive task pain is perceived as less intense, even in chronic pain patients. On the other hand, pain increases when it is the focus of attention. Functional brain imaging and neurophysiological studies have shown that attention and cognitive distraction-related modulations of nociceptive driven activations take place in various pain-sensitive cortical and subcortical brain regions, accompanied by concordant changes in pain perception.<ref name="Bantick 2002">Bantick SJ, Wise RG, Ploghaus A, Clare S, Smith SM, Tracey I. [https://academic.oup.com/brain/article/125/2/310/296978 Imaging how attention modulates pain in humans using functional MRI]. ''Brain''. 2002 Feb 1;125(2):310-9. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/brain/article/125/2/310/296978 [Accessed on 12 May 2019]</ref><br> | |||

There is strong evidence that attention (and distraction) is highly effective in modulating the pain experience and demonstrate how cognitive processes can interfere with pain perception | |||

=== Fear === | === Fear === | ||

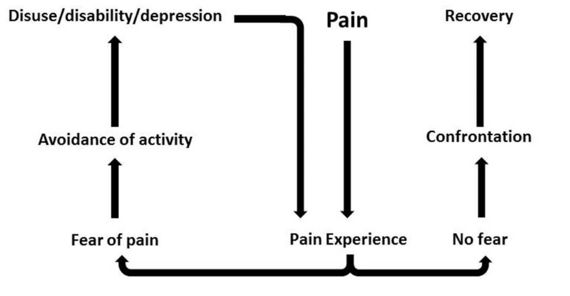

Pain-related fear is a general term to describe several forms of fear with respect to pain | [[Fear Avoidance Model|Pain-related fear]] is a general term to describe several forms of fear with respect to pain. Fear of pain can be directed toward the occurrence or continuation of pain, toward physical activity, or toward (re)-injury or physical harm. Fear toward physical activity is also known as kinesiophobia. It can be defined as “an excessive, irrational, and debilitating fear of physical movement and activity resulting from a feeling of vulnerability to painful injury or re-injury”.<ref name="Lundberg 2006">Lundberg M, Larsson M, Ostlund H, Styf J. [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Maria_Larsson2/publication/7231013_Kinesiophobia_among_patients_with_musculoskeletal_pain_in_primary_healthcare/links/0deec5273c91556bb2000000.pdf Kinesiophobia among patients with musculoskeletal pain in primary healthcare]. ''Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine''. 2006 Jan 1;38(1):37-43. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Maria_Larsson2/publication/7231013_Kinesiophobia_among_patients_with_musculoskeletal_pain_in_primary_healthcare/links/0deec5273c91556bb2000000.pdf [Accessed on 12 May 2019]</ref> If pain, possibly caused by an injury, is interpreted as threatening, pain-related fear will lead to avoidance behaviours and hypervigilance to bodily sensations. This, in turn, will lead to disability, disuse and depression. This will maintain the pain experience, thereby fueling the vicious circle of increasing fear and avoidance.<br> | ||

[[File:Fear-avoidance-picture.jpg|center|570x570px|[https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fear-avoidance_model.jpg Fear-avoidance model] | |||

]] | |||

[[ | <br> | ||

== [[Sociological Basis of Pain|Social and Cultural Factors in Pain]] == | |||

Culturally-specific attitudes and beliefs about pain can influence the manner in which individuals view and respond both to their own pain and to the pain of others | Culturally-specific attitudes and beliefs about pain can influence the manner in which individuals view and respond both to their own pain and to the pain of others. Cultural factors related to the pain experience include pain expression, pain language, lay remedies for pain, social roles, expectations and perceptions of the medical care system.<ref name="Shavers 2010">Shavers VL, Bakos A, Sheppard VB. [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Vanessa_Sheppard/publication/41510004_Race_Ethnicity_and_Pain_among_the_US_Adult_Population/links/55761d4708ae75363751a782.pdf Race, ethnicity, and pain among the US adult population]. ''Journal of health care for the poor and underserved''. 2010;21(1):177-220. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Vanessa_Sheppard/publication/41510004_Race_Ethnicity_and_Pain_among_the_US_Adult_Population/links/55761d4708ae75363751a782.pdf [Accessed on 12 May 2019]</ref><br> | ||

Another psychosocial factor that may influence differences in pain | Another psychosocial factor that may influence differences in pain responses is the gender role. Individuals who considered themselves more masculine and less sensitive to pain have been shown to have higher pain thresholds and tolerances.<ref name="Alabas 2012">Alabas OA, Tashani OA, Tabasam G, Johnson MI. [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00121.x Gender role affects experimental pain responses: a systematic review with meta‐analysis]. ''European Journal of Pain''. 2012 Oct;16(9):1211-23. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00121.x [Accessed on 12 May 2019]</ref><br> | ||

Socioeconomic factors (e.g. lower levels of education and income) | Socioeconomic factors (e.g. lower levels of education and income) seem to correlate with a higher incidence of chronic pain diagnosis and pain perception level.<ref name="Miljkovic 2014">Miljković A, Stipčić A, Braš M, Đorđević V, Brajković L, Hayward C, Pavić A, Kolčić I, Polašek O. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4111652/ Is experimentally induced pain associated with socioeconomic status? Do poor people hurt more?]. ''Medical science monitor: international medical journal of experimental and clinical research''. 2014;20:1232. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4111652/ [Accessed on 12 May 2019]</ref><br> | ||

== | == Clinical Implications == | ||

There is a direct relationship between physiological, psychological, and social factors in any individual's pain experience.<ref name="Moseley 2007" /> This can perpetuate or may even worsen the clinical presentation.<ref name="Gatchel 2007" /><br> | |||

* There is a need for sound knowledge of how these factors interact. Clinicians must have the knowledge of not only anatomy, biomechanics and pathophysiology etc., but also of diagnostic tools, outcome measures, tissue healing, peripheral and central sensitisation, and any psychological and social factors that could influence the patient's perception of pain.<ref name="Moseley 2007" /> | |||

* Patients should be helped and taught to base their reasoning about their condition and their pain on similar information as mentioned in the previous point. It is important to teach patients about more modern pain neuroscience in a way that they could understand. This could help them to change their attitudes and beliefs about pain and decrease chronic pain and disability.<ref name="Moseley 2007" /> | |||

* Targeting psychosocial factors should be a key component of any pain intervention. Treatment programs must be individually-tailored in order to specifically address the patients' attitudes and beliefs to improve treatment adherence and outcome. Treatments should also be targeted at the different pain mechanisms responsible. <ref name="Woolf 2010" /> | |||

*Targeting psychosocial factors should be a key component of | |||

== Resources == | == Resources == | ||

=== Other [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Main_Page Physiopedia] Pages === | === Other [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Main_Page Physiopedia] Pages === | ||

* [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Category:Pain All Physiopedia pages with PAIN as their category.] | |||

* [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Psychological_approaches_to_pain_management Psychological approaches to pain management] | |||

* [[Psychological Basis of Pain]] | |||

* [[Pain Mechanisms]] | |||

* [[Pain Behaviours]] | |||

=== External links === | === External links === | ||

*[http://www.iasp-pain.org/ International Asociation for the | *[http://www.iasp-pain.org/ International Asociation for the Study of Pain (IASP)] (website) | ||

*[https://www.painscience.com/ Pain Science] | *[https://www.painscience.com/ Pain Science] (website) | ||

*[http://www.pain-ed.com/ Pain-ed] | *[http://www.pain-ed.com/ Pain-ed] (website) | ||

*[ | *[https://bodyinmind.org Body in Mind] (website) | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

[[Category:Pain]] [[Category:PPA_Project]] | [[Category:Pain]] | ||

[[Category:PPA_Project]] | |||

[[Category:Physiology]] | |||

[[Category:Neurology]] | |||

[[Category:Course Pages]] | |||

[[Category:Plus Content]] | |||

Latest revision as of 11:20, 18 August 2022

Original Editor - Alberto Bertaggia.

Top Contributors - Alberto Bertaggia, Nina Myburg, Admin, Kim Jackson, Vidya Acharya, Michelle Lee, Lauren Lopez, 127.0.0.1, WikiSysop, Jess Bell and Jo Etherton

Introduction[edit | edit source]

A definition of pain is provided by the International association for the Study of Pain (IASP) as follows:[1]

An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage

Pain is always subjective and everyone learns the use of this word through experiences related to injury in early life.

Pain is a sensation in a part or parts of the body. It can vary in intensity, quality, duration and pain can refer to other parts of the body. Pain is usually an unpleasant sensation and therefore it also has an emotional aspect. It is strongly linked to suffering.[2]

Even in the absence of tissue damage or any likely pathophysiological cause, people still report pain. This could happen for psychological reasons. In these cases, it is challenging to distinguish whether someone's experience of pain arises from damaged tissue or not, as it can only be based upon the subjective report of such experience.[3]

In the following video, Karen D. Davis tries to explain why some people react to the same painful stimulus in different ways.

The Process of Feeling Pain[edit | edit source]

Pain is a physiological protective system. It is essential to warn, detect, and minimize contact with damaging stimuli.[5] Nerve endings and sensory receptors in the skin and tissues detect sensory stimuli. This can be thermal, mechanical or chemical stimuli (heat, cold, pressure, etc.). Nociceptors (from the Latin word nocere that means "to hurt") are sensory receptors that respond to damaging or potentially damaging stimuli. With the stimulation of a nociceptor, a noxious stimulus is converted into electrical activity in the peripheral terminals of nociceptor sensory fibres. This is called transduction. The stimulus is carried to the spinal cord (central nervous system) through a process called conduction. The nociceptive nerve fibres terminate and the synaptic transfer and modulation of input from one neuron to another take place. This is called transmission. The neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord transfer nociceptive input to the brainstem, hypothalamus, thalamus and brain cortex. In the brain perception of the experience occurs. This is a subjective process. Only then does the brain create pain as output after processing the stimuli. It is important to underline that activity induced in the nociceptive pathways by a noxious stimulus does not always lead to pain. Nociceptors can be stimulated by potentially damaging stimuli as well as actual damaging stimuli. Only when the brain has processed the stimulus, will it lead to a response of pain or not. Pain is always the output of a widely distributed neural network in the brain rather than one coming directly by sensory input evoked by injury, inflammation or other pathology[6].

Pain Classification[edit | edit source]

Based on the works of Woolf[5], this is a useful way of classifying pain:

- Nociceptive pain. This kind of pain is concerned with the sensing of noxious stimuli. It is a signal of impending or actual tissue damage and is a high-threshold pain only activated in the presence of intense stimuli. It has a protective role requiring immediate attention and responses (i.e. withdrawal reflex). For example, touching something too hot, cold or sharp

- Inflammatory pain. This second kind of pain is important to promote healing and protection of injured tissues. It increases sensory sensitivity through pain hypersensitivity and tenderness. Thus normally innocuous stimuli now elicit pain. It creates an environment which suggests avoidance of movement, contact and stress of the injured body parts. This, in turn, assists in the healing of the injured body part. Inflammatory pain is caused by activation of the immune system that causes inflammation after tissue injury or infection. This type of pain can be seen as a protective mechanism, However, it still needs to be reduced in patients with ongoing inflammation, as with rheumatoid arthritis or in cases of severe or extensive injury.

- Pathological pain. This type of pain is not protective, but rather maladaptive. It is not connected to tissue damage but results from abnormal functioning of the nervous system. To note, this is a low-threshold pain. Pathological pain can occur after damage to the nervous system or even when there is no damage or inflammation, It is largely the consequence of amplified sensory signals in the central nervous system. Conditions that cause this type of pain include fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, tension-type headache, temporomandibular joint disease etc. Usually, the pain is substantial without any noxious stimulus and minimal or even no peripheral inflammation.

Acute pain is caused by noxious stimuli and is mediated by nociception. It has an early onset and serves to prevent tissue damage. This is why this type of pain is defined as adaptive, it helps to survive and to heal[2]

Chronic pain is pain continuing beyond 3 months, or after healing is complete[3]. It may arise as a consequence of tissue damage or inflammation or have no identified cause. Chronic pain is a complex condition embracing physical, social and psychological factors, consequently leading to disability, loss of independence and poor quality of life.[7]

The Biopsychosocial Model of Pain[edit | edit source]

In the past, psychological and physiological (or pathophysiological) factors were considered as separate components in a dualistic point of view. Later, the recognition that psychosocial factors, such as emotional stress and fear, could impact the reporting of symptoms, medical disorders, and response to treatment lead to the development of the biopsychosocial model of pain[8].

The bio part represents the pathophysiology of the disease or the mechanism of injury, and the relative nociception processes, it considers the physiological aspects of the pain experience.

The psychosocial part involves both emotion (the more immediate reaction to nociception and is more midbrain based) and cognition (which attach meaning to the emotional experience). These could trigger additional emotional reactions and thereby amplify the experience of pain, thus perpetuating a vicious circle of nociception, pain, distress, and disability.[8]

It could be said that psychological factors, such as fear and anxiety, play an important role in the development of chronic pain. [8]

Psychological Factors in Pain[edit | edit source]

Anxiety[edit | edit source]

Health anxious individuals form dysfunctional assumptions and beliefs about pain and other symptoms. This can be disease based and based on past experiences. They will have a tendency to misinterpret somatic information as catastrophic and personally threatening. Some studies report an increase in pain correlated with increased levels of anxiety.[9] Clinically, anxiety can compromise treatments as practitioners can expect to see catastrophization play a big role in these patients' report and they could report greater pain during activities. Thus, there is a need to target attentional focus and interpretation of sensations among health anxious clients.

Depression[edit | edit source]

There is strong evidence of established comorbidity of pain and depression.[10] Furthermore, when patients with pain have comorbid depression, they could experience greater pain, have a worse prognosis, and more functional disability. Pain and depression are linked by neurobiological, cognitive, affective and behavioural factors. Thus, the optimal treatment approach for comorbid pain and depression should simultaneously address both physical and psychological symptoms.

Expectation[edit | edit source]

When an individual expects to experience pain, the perceived pain may vary based upon the types of cues received (i.e. a cue may indicate a more intense or damaging stimulus, then more intense pain is perceived and vice versa). Cues of an impending treatment could also decrease pain, for example, the process of taking an analgesic, usually decreases pain.[9] Thus, expectation is thought to play a big role in the placebo effect.

Attention and Distraction[edit | edit source]

There is strong evidence that attention (and distraction) is highly effective in modulating the pain experience and demonstrate how cognitive processes can interfere with pain perception. When a person is distracted with a cognitive task pain is perceived as less intense, even in chronic pain patients. On the other hand, pain increases when it is the focus of attention. Functional brain imaging and neurophysiological studies have shown that attention and cognitive distraction-related modulations of nociceptive driven activations take place in various pain-sensitive cortical and subcortical brain regions, accompanied by concordant changes in pain perception.[11]

Fear[edit | edit source]

Pain-related fear is a general term to describe several forms of fear with respect to pain. Fear of pain can be directed toward the occurrence or continuation of pain, toward physical activity, or toward (re)-injury or physical harm. Fear toward physical activity is also known as kinesiophobia. It can be defined as “an excessive, irrational, and debilitating fear of physical movement and activity resulting from a feeling of vulnerability to painful injury or re-injury”.[12] If pain, possibly caused by an injury, is interpreted as threatening, pain-related fear will lead to avoidance behaviours and hypervigilance to bodily sensations. This, in turn, will lead to disability, disuse and depression. This will maintain the pain experience, thereby fueling the vicious circle of increasing fear and avoidance.

Social and Cultural Factors in Pain[edit | edit source]

Culturally-specific attitudes and beliefs about pain can influence the manner in which individuals view and respond both to their own pain and to the pain of others. Cultural factors related to the pain experience include pain expression, pain language, lay remedies for pain, social roles, expectations and perceptions of the medical care system.[13]

Another psychosocial factor that may influence differences in pain responses is the gender role. Individuals who considered themselves more masculine and less sensitive to pain have been shown to have higher pain thresholds and tolerances.[14]

Socioeconomic factors (e.g. lower levels of education and income) seem to correlate with a higher incidence of chronic pain diagnosis and pain perception level.[15]

Clinical Implications[edit | edit source]

There is a direct relationship between physiological, psychological, and social factors in any individual's pain experience.[9] This can perpetuate or may even worsen the clinical presentation.[8]

- There is a need for sound knowledge of how these factors interact. Clinicians must have the knowledge of not only anatomy, biomechanics and pathophysiology etc., but also of diagnostic tools, outcome measures, tissue healing, peripheral and central sensitisation, and any psychological and social factors that could influence the patient's perception of pain.[9]

- Patients should be helped and taught to base their reasoning about their condition and their pain on similar information as mentioned in the previous point. It is important to teach patients about more modern pain neuroscience in a way that they could understand. This could help them to change their attitudes and beliefs about pain and decrease chronic pain and disability.[9]

- Targeting psychosocial factors should be a key component of any pain intervention. Treatment programs must be individually-tailored in order to specifically address the patients' attitudes and beliefs to improve treatment adherence and outcome. Treatments should also be targeted at the different pain mechanisms responsible. [5]

Resources[edit | edit source]

Other Physiopedia Pages[edit | edit source]

- All Physiopedia pages with PAIN as their category.

- Psychological approaches to pain management

- Psychological Basis of Pain

- Pain Mechanisms

- Pain Behaviours

External links[edit | edit source]

- International Asociation for the Study of Pain (IASP) (website)

- Pain Science (website)

- Pain-ed (website)

- Body in Mind (website)

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ International Association for the Study of Pain. IASP Terminology. Available from: https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1698. [Accessed 19 July 2020]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Woolf CJ. Pain: moving from symptom control toward mechanism-specific pharmacologic management. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:441-51. Available from: http://www.smbs.buffalo.edu/acb/neuro/readings/SensitizMolecMech.pdf [Accessed 12 May 2019]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Merskey H (ed.), Bogduk N (ed.). Classification of chronic pain; Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. 2nd ed. Seattle: IASP Press; 1994 Available from: https://s3.amazonaws.com/rdcms-iasp/files/production/public/Content/ContentFolders/Publications2/FreeBooks/Classification-of-Chronic-Pain.pdf [Accessed on 10 May 2019]

- ↑ TED-Ed. How does your brain respond to pain? - Karen D. Davis Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I7wfDenj6CQ&feature=emb_logo

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Woolf CJ. What is this thing called pain?. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010 Nov 1;120(11):3742-4. Available from: https://www.jci.org/articles/view/45178/pdf [Accessed on 10 May 2019]

- ↑ Dubin AE, Patapoutian A. Nociceptors: the sensors of the pain pathway. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010 Nov 1;120(11):3760-72. Available from: https://www.jci.org/articles/view/42843/pdf [Accessed on 10 May 2019]

- ↑ Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. European journal of pain. 2006 May;10(4):287–333. Available from: http://www.nascholingnoord.nl/presentaties/2012_02_02_Breivik_et_al___Survey_of_chronic_pain_in_Europe.pdf [Accessed on 12 May 2019]

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Gatchel RJ, Peng YB, Peters ML, Fuchs PN, Turk DC. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific advances and future directions. Psychological Bulletin. 2007 Jul;133(4):581. Available from: https://rc.library.uta.edu/uta-ir/bitstream/handle/10106/5000/BIOPSYCHO2006-0750-R-Final-single%20701.pdf?sequence=1 [Accessed on 12 May 2019]

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Moseley GL. Reconceptualising pain according to modern pain science. Physical therapy reviews. 2007 Sep 1;12(3):169-78. Available from: https://cdn.bodyinmind.org/wp-content/uploads/Moseley-2007-PTR-conceptualisation1.pdf [Accessed on 12 May 2019]

- ↑ Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review. Archives of internal medicine. 2003 Nov 10;163(20):2433-45. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/216320 [Accessed on 12 May 2019]

- ↑ Bantick SJ, Wise RG, Ploghaus A, Clare S, Smith SM, Tracey I. Imaging how attention modulates pain in humans using functional MRI. Brain. 2002 Feb 1;125(2):310-9. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/brain/article/125/2/310/296978 [Accessed on 12 May 2019]

- ↑ Lundberg M, Larsson M, Ostlund H, Styf J. Kinesiophobia among patients with musculoskeletal pain in primary healthcare. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2006 Jan 1;38(1):37-43. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Maria_Larsson2/publication/7231013_Kinesiophobia_among_patients_with_musculoskeletal_pain_in_primary_healthcare/links/0deec5273c91556bb2000000.pdf [Accessed on 12 May 2019]

- ↑ Shavers VL, Bakos A, Sheppard VB. Race, ethnicity, and pain among the US adult population. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved. 2010;21(1):177-220. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Vanessa_Sheppard/publication/41510004_Race_Ethnicity_and_Pain_among_the_US_Adult_Population/links/55761d4708ae75363751a782.pdf [Accessed on 12 May 2019]

- ↑ Alabas OA, Tashani OA, Tabasam G, Johnson MI. Gender role affects experimental pain responses: a systematic review with meta‐analysis. European Journal of Pain. 2012 Oct;16(9):1211-23. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00121.x [Accessed on 12 May 2019]

- ↑ Miljković A, Stipčić A, Braš M, Đorđević V, Brajković L, Hayward C, Pavić A, Kolčić I, Polašek O. Is experimentally induced pain associated with socioeconomic status? Do poor people hurt more?. Medical science monitor: international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2014;20:1232. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4111652/ [Accessed on 12 May 2019]