Effects of Ageing on Joints: Difference between revisions

Wendy Walker (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (15 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

'''Original Editor '''- Wendy Walker | '''Original Editor '''- Wendy Walker | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

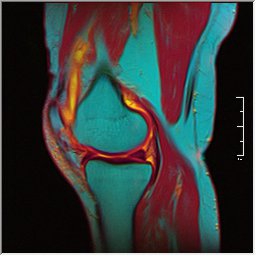

<div>No matter how healthy an individual is, as they age their joints will show some changes in mobility, due in part to changes in the connective tissues. | <div>[[File:Knee MRI 0025 07 pdfs t1 t2 59f.jpg|right|frameless]]No matter how healthy an individual is, as they age their [[Joint Classification|joints]] will show some changes in mobility, due in part to changes in the [[Connective Tissue Disorders|connective tissues.]] As joint range of movement has a direct effect on [[posture]] and [[Movement Dysfunction|movement]], this can result in marked alteration of function.</div> | ||

== Age related | == Age-related Changes in Connective Tissue == | ||

'''Cellular Changes:''' The below factors predispose the elderly to altered connective tissue biology and a decrease in effective maintenance of tissue homeostasis<ref name=":1" />. | |||

# Alterations in circulating humoral factors ([[hormones]], [[cytokines]], [[Growth Factors|growth factors]]) | |||

# Built in cellular [[Theories of Ageing|senescence]] (loss of a cell's power of division and growth) | |||

# Slower turnover of many connective tissue cell populations | |||

# Age-associated alterations in matrix molecule cross-linking | |||

# An increase in pigments and fatty substances inside the cell ([[lipids]]). Many cells lose their ability to function, or they begin to function abnormally. As aging continues, waste products build up in tissue. A fatty brown pigment called lipofuscin collects in many tissues, as do other fatty substances. | |||

# Altered control of [[apoptosis]] (programmed cell death) <ref name=":1">Freemont AJ, Hoyland JA: [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17200936 Morphology, mechanisms and pathology of musculoskeletal ageing.] J Pathol 211:252-259, 2007 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17200936 (last accessed 26.5.2019)</ref>. | |||

'''Gross Changes:''' Increased stiffness; Decreased strength; Reduction in water content | |||

=== | == Age-related Changes in Bone == | ||

<div>Bony changes have a direct effect on joint mobility, influencing the joint surfaces to alter joint mechanics. See [[Effects of Ageing on Bone|Effects of Ageing on Bone]]. Subchondral [[bone]] (the layer directly below the articular cartilage) undergoes reduction in thickness and density with increased age<ref>Yamada K, Healey R, Amiel D, et al: [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12027537 Subchondral bone of the human knee joint in aging and osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage] 10:360-369, 2002 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12027537 (last accessed 26.5.2019)</ref>. | |||

</div> | |||

== Age-related Changes in Cartilage == | |||

With [[Age and Exercise|ageing]], joint movements becomes stiffer and less flexible because the amount of [[Synovium & Synovial Fluid|synovial fluid]] inside the [[Synovial Joints|synovial joints]] decreases and the [[cartilage]] becomes thinner. Ligaments also tend to shorten and lose some [[Stretching|flexibility]], making joints feel stiff.<ref name=":0">Better health [https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/ageing-muscles-bones-and-joints Ageing- muscles bones and joints] Available from: https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/ageing-muscles-bones-and-joints (last accessed 26.5.2019)</ref> | |||

Age in the cartilage is likely due to ageing changes in cells and tissues that make the joint more susceptible to damage and less able to maintain homeostasis ie an imbalance exists between catabolic and anabolic activity driven by local production of [[Inflammation Acute and Chronic|inflammatory]] mediators in the cartilage and surrounding joint tissues. There is a close relationship between chondrocyte activity and local articular environment changes due to cell senescence, followed by secretion of inflammatory mediators.<ref>Rezuș E, Cardoneanu A, Burlui A, Luca A, Codreanu C, Tamba BI, Stanciu GD, Dima N, Bădescu C, Rezuș C. [https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/20/3/614/htm The link between inflammaging and degenerative joint diseases]. International journal of molecular sciences. 2019 Jan;20(3):614. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/20/3/614/htm (last accessed 26.5.2019)</ref> The senescent secretory phenotype likely contributes to this imbalance through the increased production of cytokines and MMPs (matrix metalloproteinases) and a reduced response to growth factors. Oxidative stress appears also to play an important role in the degradation of cartilage seen in ageing with excessive ROS (reactive oxygen species ) affecting cell function<ref>Loeser RF. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2920876/ Age-related changes in the musculoskeletal system and the development of osteoarthritis]. Clinics in geriatric medicine. 2010 Aug 1;26(3):371-86. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2920876/ (last accessed 26.5.2019)</ref>. | |||

=== | === Age-related Changes in Synovial Fluid === | ||

[[Synovium & Synovial Fluid|Synovial fluid]] lubricates joints for smooth movement. Healthy joints contains high amounts of high molar mass hyaluronic acid (HA) molecules in the synovial fluid giving it the required viscosity for its function as lubricant solution, which naturally cushion joints and other tissues. With age, the size of the hyaluronic acid molecules in joints decreases inhibiting its ability to work as effectively in support cushioning and lubrication. | |||

The video below gives an insight of the role HA plays in the joints health. Due to cellular senescence HA degrades.{{#ev:youtube|https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l0sKstpunO4&app=desktop|width}}<ref>thejocdocMD. HA and osteoarthritis of the knee Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l0sKstpunO4&app=desktop (last accessed 26.5.2019)</ref> | |||

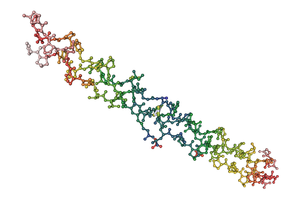

=== Age-related Changes in Collagen === | |||

[[Collagen]] is part of connective tissue, and is found in cartilage, ligaments, tendons and bones as well as [[skin]]. Collagen fibers keep your skeletal system flexible, but collagen levels in the body start to decline after about age 25. These declines can cause ligaments tendons bones and cartilage to become less flexible and more brittle over time.<ref>Schiff [https://www.schiffvitamins.com/blogs/health-wellness/how-aging-affects-your-joints How aging affects your joints] Available from: https://www.schiffvitamins.com/blogs/health-wellness/how-aging-affects-your-joints (last accessed 26.5.2019)</ref> | |||

[[File:Collagen_03.png|alt=|right|frameless]] | |||

Age-related changes in collagen (including senescence-related secretory phenotypes, chondrocytes' low reactivity to growth factors, [[Mitochondria|mitochondrial]] dysfunction and [[Free Radicals|oxidative stress,]] and abnormal accumulation of advanced glycation end products) all lead to this altered structure and decreased functional ability in collagen (Image Collagen triple helix).<ref>Li Y, Wei X, Zhou J, Wei L. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3736507/ The age-related changes in cartilage and osteoarthritis]. BioMed research international. 2013;2013. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3736507/ (last accessed 26.5.2019)</ref> | |||

== | == Range of Movement == | ||

Joint range of movement (ROM) decreases with increasing age. Passive and active [[Range of Motion|ROM]] both decrease however often the active ROM reduces more than the passive ROM. This reduction in ROM is not uniform, and different joints show different degrees of restricted movement, as well as different patterns of directional limitations. The reduction in joint movement maybe related to different patterns of daily living usage. | |||

Joint | '''Specific Joint ROM Changes''' | ||

# [[Cervical Anatomy|Cervical spine]] - extension and side flexion show the greatest reduction in ROM. | |||

# [[Thoracic Anatomy|Thoracic]] and [[lumbar]] spine - extension is the most limited movement in older adults and rotation shows little or no age-dependent decline<ref>Bible JE, Simpson AK, Emerson JW, et al: Quantifying the effects of degeneration and other patient factors on lumbar segmental range of motion using multivariate analysis. Spine 33:1793-1799, 2008</ref>. | |||

# [[Hip Anatomy|Hip]] - extension ROM has been shown to reduce by 20% when comparing 25 to 39 year olds to 60 to 74 year olds. | |||

# [[Ankle & Foot|Ankle]] - dorsiflexion ROM is reduced with age. | |||

# Upper limb: there is less influence of age on joint ROM (compared to spine and lower limb). | |||

# The [[shoulder]] complex shows the greatest changes in the upper limb, whereas no age-associated decline in ROM of the elbow or wrist have been noted<ref>Doriot N, Wang X: Effects of age and gender on maximum voluntary range of motion of the upper body joints. Ergonomics 49:269-281, 2006</ref> (in the absence of disease). | |||

[[File:Exercise older person.jpg|right|frameless]] | |||

=== | == Physiotherapy == | ||

Exercise can prevent many age-related changes to muscles, bones and joints – and reverse these changes as well. It’s never too late to start living an active lifestyle and enjoying the benefits. | |||

# Exercise can help slow the rate of [[Osteoporosis|bone loss]] and make bones stronger. | |||

# Older people can increase [[Muscle Function and Protein|muscle mass]] and strength through muscle-strengthening activities. | |||

# [[Balance]] and [[Coordination Exercises|coordination]] exercises, such as [[Tai Chi and the older person|tai chi]], can help reduce the risk of [[Falls in elderly|falls]]. | |||

# Physical activity in later life may delay the progression of [[osteoporosis]] as it slows down the rate at which bone mineral density is reduced. | |||

# [[Weight bearing|Weight-bearing exercise]], such as walking (with [[Walking Poles|walking poles]] increases arm bone density) or [[Strength Training|weight]] training, is the best type of exercise for maintenance of bone mass. There is a suggestion that twisting or rotational movements, where the muscle attachments pull on the bone, are also beneficial. | |||

# Older people who participate in [[hydrotherapy]] (which is not [[weight bearing]]) still experience increases in bone and muscle mass compared to sedentary older people. | |||

# [[Stretching]] also is excellent to help maintain joint flexibility.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

[[File:Breast_Cancer_Exercise_Classes.jpg|alt=|right|frameless]] | |||

== References == | |||

== References == | |||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Older_People/ | [[Category:Older_People/Geriatrics]] | ||

Latest revision as of 02:33, 14 August 2022

Original Editor - Wendy Walker

Top Contributors - Lucinda hampton, Wendy Walker, WikiSysop, Lauren Lopez, Tony Lowe and Laura Ritchie

Introduction[edit | edit source]

[edit | edit source]

Cellular Changes: The below factors predispose the elderly to altered connective tissue biology and a decrease in effective maintenance of tissue homeostasis[1].

- Alterations in circulating humoral factors (hormones, cytokines, growth factors)

- Built in cellular senescence (loss of a cell's power of division and growth)

- Slower turnover of many connective tissue cell populations

- Age-associated alterations in matrix molecule cross-linking

- An increase in pigments and fatty substances inside the cell (lipids). Many cells lose their ability to function, or they begin to function abnormally. As aging continues, waste products build up in tissue. A fatty brown pigment called lipofuscin collects in many tissues, as do other fatty substances.

- Altered control of apoptosis (programmed cell death) [1].

Gross Changes: Increased stiffness; Decreased strength; Reduction in water content

[edit | edit source]

[edit | edit source]

With ageing, joint movements becomes stiffer and less flexible because the amount of synovial fluid inside the synovial joints decreases and the cartilage becomes thinner. Ligaments also tend to shorten and lose some flexibility, making joints feel stiff.[3]

Age in the cartilage is likely due to ageing changes in cells and tissues that make the joint more susceptible to damage and less able to maintain homeostasis ie an imbalance exists between catabolic and anabolic activity driven by local production of inflammatory mediators in the cartilage and surrounding joint tissues. There is a close relationship between chondrocyte activity and local articular environment changes due to cell senescence, followed by secretion of inflammatory mediators.[4] The senescent secretory phenotype likely contributes to this imbalance through the increased production of cytokines and MMPs (matrix metalloproteinases) and a reduced response to growth factors. Oxidative stress appears also to play an important role in the degradation of cartilage seen in ageing with excessive ROS (reactive oxygen species ) affecting cell function[5].

[edit | edit source]

Synovial fluid lubricates joints for smooth movement. Healthy joints contains high amounts of high molar mass hyaluronic acid (HA) molecules in the synovial fluid giving it the required viscosity for its function as lubricant solution, which naturally cushion joints and other tissues. With age, the size of the hyaluronic acid molecules in joints decreases inhibiting its ability to work as effectively in support cushioning and lubrication.

The video below gives an insight of the role HA plays in the joints health. Due to cellular senescence HA degrades.

[edit | edit source]

Collagen is part of connective tissue, and is found in cartilage, ligaments, tendons and bones as well as skin. Collagen fibers keep your skeletal system flexible, but collagen levels in the body start to decline after about age 25. These declines can cause ligaments tendons bones and cartilage to become less flexible and more brittle over time.[7]

Age-related changes in collagen (including senescence-related secretory phenotypes, chondrocytes' low reactivity to growth factors, mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, and abnormal accumulation of advanced glycation end products) all lead to this altered structure and decreased functional ability in collagen (Image Collagen triple helix).[8]

Range of Movement[edit | edit source]

Joint range of movement (ROM) decreases with increasing age. Passive and active ROM both decrease however often the active ROM reduces more than the passive ROM. This reduction in ROM is not uniform, and different joints show different degrees of restricted movement, as well as different patterns of directional limitations. The reduction in joint movement maybe related to different patterns of daily living usage.

Specific Joint ROM Changes

- Cervical spine - extension and side flexion show the greatest reduction in ROM.

- Thoracic and lumbar spine - extension is the most limited movement in older adults and rotation shows little or no age-dependent decline[9].

- Hip - extension ROM has been shown to reduce by 20% when comparing 25 to 39 year olds to 60 to 74 year olds.

- Ankle - dorsiflexion ROM is reduced with age.

- Upper limb: there is less influence of age on joint ROM (compared to spine and lower limb).

- The shoulder complex shows the greatest changes in the upper limb, whereas no age-associated decline in ROM of the elbow or wrist have been noted[10] (in the absence of disease).

Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Exercise can prevent many age-related changes to muscles, bones and joints – and reverse these changes as well. It’s never too late to start living an active lifestyle and enjoying the benefits.

- Exercise can help slow the rate of bone loss and make bones stronger.

- Older people can increase muscle mass and strength through muscle-strengthening activities.

- Balance and coordination exercises, such as tai chi, can help reduce the risk of falls.

- Physical activity in later life may delay the progression of osteoporosis as it slows down the rate at which bone mineral density is reduced.

- Weight-bearing exercise, such as walking (with walking poles increases arm bone density) or weight training, is the best type of exercise for maintenance of bone mass. There is a suggestion that twisting or rotational movements, where the muscle attachments pull on the bone, are also beneficial.

- Older people who participate in hydrotherapy (which is not weight bearing) still experience increases in bone and muscle mass compared to sedentary older people.

- Stretching also is excellent to help maintain joint flexibility.[3]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Freemont AJ, Hoyland JA: Morphology, mechanisms and pathology of musculoskeletal ageing. J Pathol 211:252-259, 2007 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17200936 (last accessed 26.5.2019)

- ↑ Yamada K, Healey R, Amiel D, et al: Subchondral bone of the human knee joint in aging and osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 10:360-369, 2002 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12027537 (last accessed 26.5.2019)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Better health Ageing- muscles bones and joints Available from: https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/ageing-muscles-bones-and-joints (last accessed 26.5.2019)

- ↑ Rezuș E, Cardoneanu A, Burlui A, Luca A, Codreanu C, Tamba BI, Stanciu GD, Dima N, Bădescu C, Rezuș C. The link between inflammaging and degenerative joint diseases. International journal of molecular sciences. 2019 Jan;20(3):614. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/20/3/614/htm (last accessed 26.5.2019)

- ↑ Loeser RF. Age-related changes in the musculoskeletal system and the development of osteoarthritis. Clinics in geriatric medicine. 2010 Aug 1;26(3):371-86. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2920876/ (last accessed 26.5.2019)

- ↑ thejocdocMD. HA and osteoarthritis of the knee Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l0sKstpunO4&app=desktop (last accessed 26.5.2019)

- ↑ Schiff How aging affects your joints Available from: https://www.schiffvitamins.com/blogs/health-wellness/how-aging-affects-your-joints (last accessed 26.5.2019)

- ↑ Li Y, Wei X, Zhou J, Wei L. The age-related changes in cartilage and osteoarthritis. BioMed research international. 2013;2013. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3736507/ (last accessed 26.5.2019)

- ↑ Bible JE, Simpson AK, Emerson JW, et al: Quantifying the effects of degeneration and other patient factors on lumbar segmental range of motion using multivariate analysis. Spine 33:1793-1799, 2008

- ↑ Doriot N, Wang X: Effects of age and gender on maximum voluntary range of motion of the upper body joints. Ergonomics 49:269-281, 2006