Sinding Larsen Johansson Syndrome: Difference between revisions

Michelle Lee (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Kim Jackson (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "Osgood-Schlatter's Disease" to "Osgood-Schlatter Disease") |

||

| (42 intermediate revisions by 12 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | <div class="editorbox"> | ||

'''Original Editor '''- [[User:Andrew Klaehn|Andrew Klaehn]], [[User:Yelena Gesthuizen|Yelena Gesthuizen]] as part of the [[Vrije Universiteit Brussel Evidence-based Practice Project]] | '''Original Editor '''- [[User:Andrew Klaehn|Andrew Klaehn]],[[User:Yelena Gesthuizen|Yelena Gesthuizen]] as part of the [[Vrije Universiteit Brussel Evidence-based Practice Project]] | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | |||

</div> | |||

== Definition/Description == | |||

[[File:OSG, SJS.jpeg|frameless|alt=|center]] | |||

Sinding Larsen Johansson Syndrome (SLJS) is a juvenile [https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwi4jMaV1an0AhU-zzgGHYmaArQQFnoECAMQAw&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.physio-pedia.com%2FOsteochondritis_Dissecans_of_the_Knee&usg=AOvVaw3jSyeVzfMDU8J2rtXqYV3G osteochondrosis] and traction epiphysitis affecting the extensor mechanism of the knee which disturbs the patella tendon attachment to the inferior pole of the [[patella]]. The tenderness of the inferior pole of the patella is usually accompanied by [[X-Rays|X-ray]] evidence of splintering of that pole. Most patients with SLJS also show a calcification at the inferior pole of the patella.<ref name=":8">Medlar, R. C., et al., ‘Sinding-Larsen-Johansson Disease. Its Etiology and Natural History’, Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, December 1978, vol. 60, no. 8, p. 1113-1116. (Level of Evidence 1B)</ref> | |||

The syndrome usually appears in adolescence, during the growth spurt. It’s associated with localised pain which is worsened by exercise. Usually a localised tenderness and soft tissue swelling is observed. There is also a tightness of the surrounding muscles, the [[Rectus Femoris|quadriceps]], [[hamstrings]] and [[gastrocnemius]] in particular. This tightness usually results in inflexibilities of the [[Knee|knee joint]], altering the stress through the [[Patellofemoral Joint|patellofemoral joint]].<ref>Houghton, K. M., ‘Review for the generalist: evaluation of anterior knee pain’, Paediatric Rheumatology, (2007), vol. 5, p. 4-10. (Level of Evidence 2B)</ref> | |||

''' | '''Image 1''': The site of the [[Osgood-Schlatter Disease|Osgood Schlatter]] disease and SJS on the knee. OSG at tibial tuberosity and SJS at inferior pole of patella | ||

== Classification == | |||

Medlar and Lyne classified the condition in four stages based on the radiographs. The following stages were proposed: stage I when the patella has a normal appearance, stage II if there are irregular calcifications in the distal pole, stage III with coalescence of calcifications, stage IV-a when the calcifications are coalescing into the distal pole, and stage IV-b is a calcified ossicle distinct from the distal pole<ref name=":9" />. | |||

== Epidemiology == | |||

Unlike "[https://www.physio-pedia.com/Patellar_Tendinopathy Jumper's Knee]" which is seen at any age, SLJS is seen in active adolescents, typically between 10-14 years of age. | |||

= | * Children with [[Cerebral Palsy Introduction|cerebral palsy]] are also prone to SLJS<ref name=":0">Radiopedia [https://radiopaedia.org/articles/sinding-larsen-johansson-disease Sinding-Larsen-Johansson disease] Available: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/sinding-larsen-johansson-disease (accessed 13.10.2021)</ref>. | ||

== Etiology == | |||

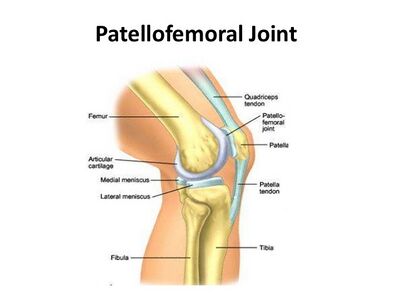

[[File:PFJ-1-4-20-638.jpg|right|frameless|399x399px]] | |||

SLJS is caused by traction on the patellar ligament, causing inflammation at the insertion of the proximal ligament into the inferior pole of the patella. | |||

The | The extensor mechanism of the knee comprises the quadriceps tendon and muscles, patella, patellar ligament and the supporting retinaculum. Injuries can occur from direct trauma, overuse, degenerative disease. The most common adolescent injury to this area is Osgood-Schlatter’s disease, which affects the distal pole of the patellar tendon and tibial tubercle.<ref name=":9">The sports medicine review SINDING-LARSEN-JOHANSSON SYNDROME Available: https://www.sportsmedreview.com/blog/sinding-larsen-johansson-syndrome/ (accessed 13.10.20210</ref> | ||

== | == Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | ||

Physical examination is important for the diagnosis of SLJS, as with most conditions. Most will have tenderness at the inferior pole of the patella and there may be some tenderness along the patellar tendon. Resisted knee extension may elicit pain and there may be some localized soft tissue swelling. A joint effusion should not be present with this condition and may be present with a patellar sleeve avulsion fracture.<ref name=":9" /> | |||

Patients are typically young active boys aged 10 to 13 years. Symptoms are usually; | |||

* Worse with exercise, stair climbing, squatting, kneeling, jumping and running. | |||

* May report that they limp after exercise. | |||

* May be unilateral or bilateral. | |||

* Is relieved by rest | |||

Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome is a self-limiting syndrome. Complete recovery can be expected with closure of the patella growth plate. Although symptoms of Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome may linger for months, few patients have poor outcomes with conservative treatment, and surgical intervention is generally not necessary. Corticosteroid injections are not recommended due to case reports of subcutaneous atrophy.<ref>http://physioworks.com.au/injuries-conditions-1/sinding-larsen-johansson-disease</ref> | |||

== Differential Diagnosis == | |||

Differential considerations include: | |||

* Osgood-Schlatter disease: occurs at the inferior attachment of the patellar tendon onto the tibial tuberosity | |||

* Jumper's knee: same location and similar pathology, but seen in adults (some authors do not distinguish between Sinding-Larsen-Johansson and jumper's knee). | |||

* Patellar sleeve fractures: same age group; avulsion of inferior pole cartilage, often with small fracture fragment | |||

* Bipartite patella/normal inferior pole "fragmentation" | |||

* Infrapatellar bursitis: fluid signal is located anteriorly to the patellar tendon<ref name=":0" /> | |||

== Diagnostic Procedures == | == Diagnostic Procedures == | ||

The physiotherapist performs a physical examination of the knee and reviews the patient’s symptoms. In case of anterior knee pain there are three important tests to perform. In all tests the patient is in supine position. | |||

# [[Patellar Grind Test]]<ref>http://slideplayer.com/slide/4311148/, Hip, Thigh, and Knee. ILIUM Acetabulum Ischium Ischial Tuberosity Pubis. (Photo)</ref>;Tester places thumb web-space just above the patella, then asks to contract their quad forcefully. The test is positive if there is pain or grinding. | |||

# [[Spurling's Test|Compression Test]]<ref>http://www.slideshare.net/JLS10/kin191-ach6kneepatellofemoralevaluation (Photo) | |||

</ref><ref>http://www.fpnotebook.com/ortho/exam/AplysCmprsnTst.htm (Photo)</ref>; Hard downward pressure is applied with rotation, pain indicates [[Meniscal Lesions|meniscal]] injury. | |||

# [[Knee Extension Resistance Test|Extension Resistance Test]]<ref>https://meded.ucsd.edu/clinicalmed/neuro2.htm (Photo)</ref> | |||

== Outcome Measures == | |||

The [https://www.hss.edu/secure/files/WSMC-kujala.pdf Kujala anterior knee pain scale] and the [[Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS)|Lower extremity functional scale]] can be used for both an initial screening tool as well as to detect changes with treatment and as outcome measures. | |||

== | == Treatment == | ||

Initial treatment consists of relieving the pain by resting for a few days and strengthening exercises with modification of activities. There is no definite protocol or treatment algorithm that exists for SLJS. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs ([[NSAIDs]]) may be necessary, and in severe cases a cast is used for maintaining immobility. This is usually done for up to 4 weeks, but most cases do not require this. Many can perform weight bearing as tolerated and physical therapy may be prescribed. | |||

* Two separate reports have shown an average return to sport in 4-14 weeks with the average age of 8 to 14 years old with almost all cases happening in athletes, with soccer and males being more common. | |||

* Treatment is typically guided by pain and activities. Crutches may be needed if limping is occurring and an experienced physical therapist or athletic trainer can aid in progression and return to activity or sport. | |||

* Surgical debridement, which will remove the necrotic intratendinous tissue should be the last resort for patients who are resistant to conservative management.<ref name=":9" /> | |||

== Physical Therapy Treatment == | |||

The physical therapist must educate the patient on activity modification. | |||

Kneeling, jumping, squatting, stair climbing, and running on the affected knee should be avoided at least for the short term. | |||

Lower extremity strength needs to be tested, especially at the ankle and the hip to find any muscle weaknesses that may be contributing to the overuse syndrome. | |||

[[ | Core strengthening should be initiated as well as exercise addressing flexibility or strength issues. <ref name=":2">Klucinec, B., ‘Recalcitrant Infrapatellar Tendinitis and Surgical Outcome in a Collegiate Basketball Player: A Case Report’, Journal of Athletic Training, June 2001, vol. 36, no. 2, p. 174-181. (Level of Evidence 1C)</ref> <br>Therapy should consist of eccentric exercises and isokinetic strengthening.<ref name=":1">Demetrious, T. and B., Harrop (red.), Sinding-Larsen-Johansson Disease, internet, 2008, (http://www.physioadvisor.com.au/10246650/sindinglarsenjohansson-disease-physioadvisor.htm). (Level of Evidence 5)</ref> <br> | ||

[[File:Lunge stretch of the calf muscles.png|none|thumb|366x366px|Example of a standing calf stretch.]] | |||

[[File:Hamstring Stretch.png|thumb|200x200px|Hamstring stretch.]] | |||

<br>If the patient doesn’t respond (the pain doesn’t decrease), it can be possible to give platelet-rich plasma injections. These are given in the synchondrosis area under ultrasound guidance.<ref name=":1" /> <br>Stretching and [[Proprioception|proprioceptive]] muscle strengthening exercises in patients with anterior knee pain, have been proven beneficial.<ref name=":5">Clark, D.I., et al., ‘Physiotherapy for Anterior Knee Pain. A Randomised Controlled Trial’, Ann Rheum Dis, 2000, 59, p. 700-704. (Level of Evidence 1B)</ref> An improvement of strength and functionality can be accomplished by both open and closed kinetic chain exercises.<ref>Witvrouw, E., et al., ‘Open Versus Closed Kinetic Chain Exercises for Patellofemoral Pain. A Prospective Randomised Study’, The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 2000, vol. 28, no. 5, p. 687-694. (Level of Evidence 1B)</ref> <br>Patients who followed a 30 to 60 minute physical therapy intervention, once a week during six weeks showed a decrease in patellofemoral pain.<ref name=":6">Crossley, K., et al., ‘Physical Therapy for Patellofemoral Pain. A Randomised, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial’, The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 2002, vol. 30, no. 6, p. 856-865. (Level of Evidence 1B)</ref> | |||

<br> | <br>A safe progression back to sports or high-level activities may happen when each of the following happens in this specific order: | ||

* The lower kneecap is no longer tender and there is no swelling. | |||

* The injured knee can be fully straightened and bent without pain. | |||

* The knee and leg have regained normal strength compared to the uninjured knee and leg | |||

* Ability to jog straight ahead without limping. | |||

* Ability to sprint straight ahead without limping. | |||

* Ability to do 45-degree cuts. | |||

* Ability to do 90-degree cuts. | |||

* Ability to do 20-yard figure-of-eight runs. | |||

* Ability to do 10-yard figure-of-eight runs. | |||

* Ability to jump on both legs without pain and hop on the injured leg without pain.<ref name=":6" /> | |||

< | If there has been no progress, then an operation may be necessary. After the operation full weight bearing is allowed with two canes without an immobilisation splint for the first week. Then therapy can start after one week, with knee exercises to regain joint range of motion. The first six weeks will consist of eccentric quadriceps exercises and jumping and other more functional movements are allowed after three months. This strategy was, again, used for only one specific patient and is not fully researched.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

== References == | |||

[[Category: | [[Category:Primary Contact]] | ||

[[Category:Syndromes]] | |||

<references /> | |||

[[Category:Sports Medicine]] | |||

[[Category:Sports Injuries]] | |||

[[Category:Younger Athlete]] | |||

[[Category:Paediatrics - Conditions]] | |||

Latest revision as of 11:28, 28 February 2022

Original Editor - Andrew Klaehn,Yelena Gesthuizen as part of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel Evidence-based Practice Project

Top Contributors - Admin, Yelena Gesthuizen, Laure VanderDonckt, Andrew Klaehn, Michelle Lee, Adam Vallely Farrell, Lucinda hampton, Wanda van Niekerk, Kim Jackson, Charlotte Moreau, Candace Goh, Claire Knott, Rucha Gadgil, Jess Bell, Naomi O'Reilly, Gitte Verdoodt and 127.0.0.1

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Sinding Larsen Johansson Syndrome (SLJS) is a juvenile osteochondrosis and traction epiphysitis affecting the extensor mechanism of the knee which disturbs the patella tendon attachment to the inferior pole of the patella. The tenderness of the inferior pole of the patella is usually accompanied by X-ray evidence of splintering of that pole. Most patients with SLJS also show a calcification at the inferior pole of the patella.[1]

The syndrome usually appears in adolescence, during the growth spurt. It’s associated with localised pain which is worsened by exercise. Usually a localised tenderness and soft tissue swelling is observed. There is also a tightness of the surrounding muscles, the quadriceps, hamstrings and gastrocnemius in particular. This tightness usually results in inflexibilities of the knee joint, altering the stress through the patellofemoral joint.[2]

Image 1: The site of the Osgood Schlatter disease and SJS on the knee. OSG at tibial tuberosity and SJS at inferior pole of patella

Classification[edit | edit source]

Medlar and Lyne classified the condition in four stages based on the radiographs. The following stages were proposed: stage I when the patella has a normal appearance, stage II if there are irregular calcifications in the distal pole, stage III with coalescence of calcifications, stage IV-a when the calcifications are coalescing into the distal pole, and stage IV-b is a calcified ossicle distinct from the distal pole[3].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Unlike "Jumper's Knee" which is seen at any age, SLJS is seen in active adolescents, typically between 10-14 years of age.

- Children with cerebral palsy are also prone to SLJS[4].

Etiology[edit | edit source]

SLJS is caused by traction on the patellar ligament, causing inflammation at the insertion of the proximal ligament into the inferior pole of the patella.

The extensor mechanism of the knee comprises the quadriceps tendon and muscles, patella, patellar ligament and the supporting retinaculum. Injuries can occur from direct trauma, overuse, degenerative disease. The most common adolescent injury to this area is Osgood-Schlatter’s disease, which affects the distal pole of the patellar tendon and tibial tubercle.[3]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Physical examination is important for the diagnosis of SLJS, as with most conditions. Most will have tenderness at the inferior pole of the patella and there may be some tenderness along the patellar tendon. Resisted knee extension may elicit pain and there may be some localized soft tissue swelling. A joint effusion should not be present with this condition and may be present with a patellar sleeve avulsion fracture.[3]

Patients are typically young active boys aged 10 to 13 years. Symptoms are usually;

- Worse with exercise, stair climbing, squatting, kneeling, jumping and running.

- May report that they limp after exercise.

- May be unilateral or bilateral.

- Is relieved by rest

Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome is a self-limiting syndrome. Complete recovery can be expected with closure of the patella growth plate. Although symptoms of Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome may linger for months, few patients have poor outcomes with conservative treatment, and surgical intervention is generally not necessary. Corticosteroid injections are not recommended due to case reports of subcutaneous atrophy.[5]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Differential considerations include:

- Osgood-Schlatter disease: occurs at the inferior attachment of the patellar tendon onto the tibial tuberosity

- Jumper's knee: same location and similar pathology, but seen in adults (some authors do not distinguish between Sinding-Larsen-Johansson and jumper's knee).

- Patellar sleeve fractures: same age group; avulsion of inferior pole cartilage, often with small fracture fragment

- Bipartite patella/normal inferior pole "fragmentation"

- Infrapatellar bursitis: fluid signal is located anteriorly to the patellar tendon[4]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

The physiotherapist performs a physical examination of the knee and reviews the patient’s symptoms. In case of anterior knee pain there are three important tests to perform. In all tests the patient is in supine position.

- Patellar Grind Test[6];Tester places thumb web-space just above the patella, then asks to contract their quad forcefully. The test is positive if there is pain or grinding.

- Compression Test[7][8]; Hard downward pressure is applied with rotation, pain indicates meniscal injury.

- Extension Resistance Test[9]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

The Kujala anterior knee pain scale and the Lower extremity functional scale can be used for both an initial screening tool as well as to detect changes with treatment and as outcome measures.

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Initial treatment consists of relieving the pain by resting for a few days and strengthening exercises with modification of activities. There is no definite protocol or treatment algorithm that exists for SLJS. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be necessary, and in severe cases a cast is used for maintaining immobility. This is usually done for up to 4 weeks, but most cases do not require this. Many can perform weight bearing as tolerated and physical therapy may be prescribed.

- Two separate reports have shown an average return to sport in 4-14 weeks with the average age of 8 to 14 years old with almost all cases happening in athletes, with soccer and males being more common.

- Treatment is typically guided by pain and activities. Crutches may be needed if limping is occurring and an experienced physical therapist or athletic trainer can aid in progression and return to activity or sport.

- Surgical debridement, which will remove the necrotic intratendinous tissue should be the last resort for patients who are resistant to conservative management.[3]

Physical Therapy Treatment[edit | edit source]

The physical therapist must educate the patient on activity modification.

Kneeling, jumping, squatting, stair climbing, and running on the affected knee should be avoided at least for the short term.

Lower extremity strength needs to be tested, especially at the ankle and the hip to find any muscle weaknesses that may be contributing to the overuse syndrome.

Core strengthening should be initiated as well as exercise addressing flexibility or strength issues. [10]

Therapy should consist of eccentric exercises and isokinetic strengthening.[11]

If the patient doesn’t respond (the pain doesn’t decrease), it can be possible to give platelet-rich plasma injections. These are given in the synchondrosis area under ultrasound guidance.[11]

Stretching and proprioceptive muscle strengthening exercises in patients with anterior knee pain, have been proven beneficial.[12] An improvement of strength and functionality can be accomplished by both open and closed kinetic chain exercises.[13]

Patients who followed a 30 to 60 minute physical therapy intervention, once a week during six weeks showed a decrease in patellofemoral pain.[14]

A safe progression back to sports or high-level activities may happen when each of the following happens in this specific order:

- The lower kneecap is no longer tender and there is no swelling.

- The injured knee can be fully straightened and bent without pain.

- The knee and leg have regained normal strength compared to the uninjured knee and leg

- Ability to jog straight ahead without limping.

- Ability to sprint straight ahead without limping.

- Ability to do 45-degree cuts.

- Ability to do 90-degree cuts.

- Ability to do 20-yard figure-of-eight runs.

- Ability to do 10-yard figure-of-eight runs.

- Ability to jump on both legs without pain and hop on the injured leg without pain.[14]

If there has been no progress, then an operation may be necessary. After the operation full weight bearing is allowed with two canes without an immobilisation splint for the first week. Then therapy can start after one week, with knee exercises to regain joint range of motion. The first six weeks will consist of eccentric quadriceps exercises and jumping and other more functional movements are allowed after three months. This strategy was, again, used for only one specific patient and is not fully researched.[11]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Medlar, R. C., et al., ‘Sinding-Larsen-Johansson Disease. Its Etiology and Natural History’, Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, December 1978, vol. 60, no. 8, p. 1113-1116. (Level of Evidence 1B)

- ↑ Houghton, K. M., ‘Review for the generalist: evaluation of anterior knee pain’, Paediatric Rheumatology, (2007), vol. 5, p. 4-10. (Level of Evidence 2B)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 The sports medicine review SINDING-LARSEN-JOHANSSON SYNDROME Available: https://www.sportsmedreview.com/blog/sinding-larsen-johansson-syndrome/ (accessed 13.10.20210

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Radiopedia Sinding-Larsen-Johansson disease Available: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/sinding-larsen-johansson-disease (accessed 13.10.2021)

- ↑ http://physioworks.com.au/injuries-conditions-1/sinding-larsen-johansson-disease

- ↑ http://slideplayer.com/slide/4311148/, Hip, Thigh, and Knee. ILIUM Acetabulum Ischium Ischial Tuberosity Pubis. (Photo)

- ↑ http://www.slideshare.net/JLS10/kin191-ach6kneepatellofemoralevaluation (Photo)

- ↑ http://www.fpnotebook.com/ortho/exam/AplysCmprsnTst.htm (Photo)

- ↑ https://meded.ucsd.edu/clinicalmed/neuro2.htm (Photo)

- ↑ Klucinec, B., ‘Recalcitrant Infrapatellar Tendinitis and Surgical Outcome in a Collegiate Basketball Player: A Case Report’, Journal of Athletic Training, June 2001, vol. 36, no. 2, p. 174-181. (Level of Evidence 1C)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Demetrious, T. and B., Harrop (red.), Sinding-Larsen-Johansson Disease, internet, 2008, (http://www.physioadvisor.com.au/10246650/sindinglarsenjohansson-disease-physioadvisor.htm). (Level of Evidence 5)

- ↑ Clark, D.I., et al., ‘Physiotherapy for Anterior Knee Pain. A Randomised Controlled Trial’, Ann Rheum Dis, 2000, 59, p. 700-704. (Level of Evidence 1B)

- ↑ Witvrouw, E., et al., ‘Open Versus Closed Kinetic Chain Exercises for Patellofemoral Pain. A Prospective Randomised Study’, The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 2000, vol. 28, no. 5, p. 687-694. (Level of Evidence 1B)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Crossley, K., et al., ‘Physical Therapy for Patellofemoral Pain. A Randomised, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial’, The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 2002, vol. 30, no. 6, p. 856-865. (Level of Evidence 1B)