Management of Ankle Sprains: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

* shoe type | * shoe type | ||

In summary these prognostic factors suggest good clinical outcome after foot and ankle injury: younger age, low grade sprain, low activity level, good functional status, good neuromuscular function, no associated injury.<ref name=":2" />Long lasting symptoms with functional limitations can be predicted based on the presence of systemic laxity, joint geometry, limb and foot malalignment, re-sprain, and multiligament injury.<ref name=":2" /> | |||

In summary these prognostic factors suggest good clinical outcome after foot and ankle injury: younger age, low grade sprain, low activity level, good functional status, good neuromuscular function, no associated injury.<ref name=":2" /> | |||

== Classification Grading Systems == | == Classification Grading Systems == | ||

Revision as of 00:26, 26 January 2022

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Ankle sprains are considered one of the most frequent traumatic type of injuries. Yeung et al, 1994, in an epidemiological study of unilateral ankle sprains, reported that the dominant leg is 2.4 times more vulnerable to sprain than the non-dominant one.[1]There were reports proposing that the greater the level of plantar flexion the higher the likelihood of sprain. [2]A conservative treatment is the common approach to ankle injury. The prognosis is generally good, but there is a number of factors influencing the full recovery.[3]These factors, when early identified, can change the treatment protocol to more aggressive approach.[3]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Lateral Ankle Sprain[edit | edit source]

The literature suggests that 85% of the ankle sprains involves lateral ligaments. [4]The anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) of the lateral ankle ligament complex is the most frequently damaged when lateral ankle sprain occurs. Their anatomical location and the mechanism of sprain injury mean that the calcaneo-fibular (CFL) and posterior talofibular ligaments (PTFL) are less likely to sustain damaging loads.

Medial Ankle Sprain[edit | edit source]

On the medial side the strong, deltoid ligament complex [posterior tibiotalar (PTTL), tibiocalcaneal (TCL), tibionavicular (TNL) and anterior tibiotalar ligaments (ATTL)] is injured with forceful "pronation and rotation movements of the hindfoot". [5]

Syndesmotic Ankle Sprain[edit | edit source]

The stabilising ligaments of the distal tibio-fibular syndesmosis are the anterior-inferior, posterior-inferior, and transverse tibio-fibular ligaments, the interosseous membrane and ligament, and the inferior transverse ligament. A syndesmotic ankle sprain occurs with combined external rotation of the leg and dorsiflexion of the ankle.

Risk Factors and Outcome[edit | edit source]

Predisposing factors are the risk factors for the ankle sprains. [3] Identifying risk factors helps the clinician to choose the most appropriate treatment regimen given the fact that those risk factors have a significant impact on the patient's recovery.[3]They are divided into two categories:intrinsic and extrinsic.

Intrinsic risk factors for outcome prediction include:[5]

- age and gender: female athletes have 25% greater risk of suffering from a grade 1 ankle sprain[6]

- height and weight: increase in height or weight proportionally increases the risk of sprain due to an increase magnitude of inversion torque

- activity level

- grade of injury

- functional status

- associated injury, especially previous sprain

- limb characteristic including limb dominance, anatomic foot type and foot size, joint laxity, anatomic alignment, range of motion of the ankle-foot complex: abnormalities in foot biomechanics such as pes planus, pes cavus, and increased hindfoot inversion were risk factors for lower extremity overuse injury[7]

- muscle strength

- posture, particularly postural sway: increased sway leads to a 7-fold increase in ankle sprains [8]

Extrinsic risk factors for outcome prediction include:

- level of competition: the higher the level, the number of ankle sprains increases

- ankle bracing or taping: introducing this intervention early on can lower incidence of ankle sprains

- shoe type

In summary these prognostic factors suggest good clinical outcome after foot and ankle injury: younger age, low grade sprain, low activity level, good functional status, good neuromuscular function, no associated injury.[3]Long lasting symptoms with functional limitations can be predicted based on the presence of systemic laxity, joint geometry, limb and foot malalignment, re-sprain, and multiligament injury.[3]

Classification Grading Systems[edit | edit source]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

add text here relating to the clinical presentation of the condition

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

add text here relating to diagnostic tests for the condition

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

add links to outcome measures here (see Outcome Measures Database)

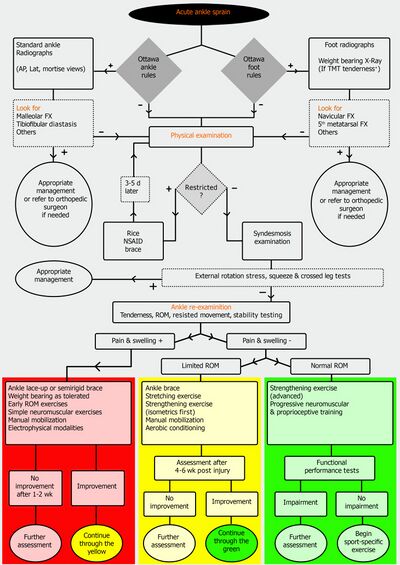

Management[edit | edit source]

Acute Phase[edit | edit source]

Subacute Phase[edit | edit source]

Chronic Phase[edit | edit source]

add text here relating to management approaches to the condition

Resources

[edit | edit source]

add appropriate resources here

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Yeung MS, Chan KM, So CH, Yuan WY. An epidemiological survey on ankle sprain. Br J Sports Med. 1994 Jun;28(2):112-6.

- ↑ Wright IC, Neptune RR, van den Bogert AJ, Nigg BM. The influence of foot positioning on ankle sprains. J Biomech. 2000 May;33(5):513-9.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Ferreira JN, Vide J, Mendes D, Protásio J, Viegas R, Sousa MR. Prognostic factors in ankle sprains: a review. EFORT Open Rev. 2020 Jun 1;5(6):334-338.

- ↑ Halabchi F, Hassabi M. Acute ankle sprain in athletes: Clinical aspects and algorithmic approach. World J Orthop. 2020 Dec 18;11(12):534-558.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Beynnon BD, Murphy DF, Alosa DM. Predictive Factors for Lateral Ankle Sprains: A Literature Review. J Athl Train. 2002 Dec;37(4):376-380.

- ↑ Hosea TM, Carey CC, Harrer MF. The gender issue: epidemiology of ankle injuries in athletes who participate in basketball. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000 Mar;(372):45-9.

- ↑ Kaufman KR, Brodine SK, Shaffer RA, Johnson CW, Cullison TR. The effect of foot structure and range of motion on musculoskeletal overuse injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1999 Sep-Oct;27(5):585-93.

- ↑ McGuine TA, Greene JJ, Best T, Leverson G. Balance as a predictor of ankle injuries in high school basketball players. Clin J Sport Med. 2000 Oct;10(4):239-44.