|

|

| (61 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| <div class="noeditbox">Welcome to [[Glasgow Caledonian University Cardiorespiratory Therapeutics Project]] This project is created by and for the students in the School of Physiotherapy at Glasgow Caledonian University. Please do not edit unless you are involved in this project, but please come back in the near future to check out new information!!</div><div class="editorbox">

| | <div class="editorbox"> |

| '''Original Editors '''- [[Glasgow Caledonian University Cardiorespiratory Therapeutics Project|Students from Glasgow Caledonian University's Cardiorespiratory Therapeutics Project.]] | | '''Original Editors '''- [[Glasgow Caledonian University Cardiorespiratory Therapeutics Project|Students from Glasgow Caledonian University's Cardiorespiratory Therapeutics Project.]] |

|

| |

|

| '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} |

| </div> | | </div> |

| == Definition/Description == | | == Introduction == |

| | [[File:Peripheral Arterial Disease.gif|right|frameless|435x435px]]Peripheral artery disease is a common type of [[Cardiovascular Disease|cardiovascular disease]], which affects 236 million people across the world. It happens when the arteries in the legs and feet become clogged with fatty plaques through a process known as [[atherosclerosis]]. |

| | |

| | While some people with this disease experience no symptoms, the most classic symptoms are [[Pain Assessment|pain]], cramps, numbness, weakness or tingling that occurs in the legs during walking – known as intermittent claudication. These problems affect around 30% of people with peripheral artery disease. Intermittent claudication is more common in adults over 50, men and people who smoke.<ref>The Conversation [https://theconversation.com/walking-can-relieve-leg-pain-in-people-with-peripheral-artery-disease-151240 Walking can relieve leg pain in people with peripheral artery disease] Available: https://theconversation.com/walking-can-relieve-leg-pain-in-people-with-peripheral-artery-disease-151240<nowiki/>(accessed 6.6.2021)</ref> |

| | |

| | The management of PAD varies depending on the disease severity and symptom status. Treatment options for PAD include lifestyle changes, cardiovascular risk factor reduction, pharmacotherapy, endovascular intervention, and [[Surgery and General Anaesthetic|surgery]].<ref name=":1">Zemaitis MR, Boll JM, Dreyer MA. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430745/ Peripheral arterial disease.] StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 Jul 6.Available :https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430745/ (accessed 6.6.2021)</ref> |

|

| |

|

| Definition of the disease or condition

| | The video below is a good summary of the basics of PAD |

| | {{#ev:youtube|https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XTSgpiPqIbk|width}}<ref>American Heart Association PAD What is it? Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XTSgpiPqIbk (last accessed 7.9.2019)</ref> |

|

| |

|

| == Epidemiology == | | == Epidemiology == |

| | [[File:Smoking-1026556 960 720-2.jpg|right|frameless]] |

| | Prevalence: 12-14%, 20% of the over 70s in Western populations<ref name=":0">Radiopedia [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430745/ PAD] Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430745/ (accessed 6.6.2021)</ref>. |

|

| |

|

| In the United Kingdom, an estimated 500-1000 new cases of PAD are diagnosed per million each year<ref name="Patient">Patient. Peripheral arterial disease. http://www.patient.co.uk/doctor/peripheral-arterial-disease (accessed 9 May 2015)</ref><ref name="Peach">Peach, G, Griffin, M, Jones, KG, Thompson MM, Hinchliffe, RJ. Diagnosis and management of peripheral arterial disease. BMJ 2012; 345: 1-8. http://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/345/bmj.e5208.full.pdf (acccessed 9 May 2015)</ref>. Patients at high risk of PAD are those with cardiac disease, diabetes mellitus, older than 70 years or 50 years old with multiple cardiovascular factors<ref name="Mahameed">Mahameed, AA, Bartholomew, JR, Disease of Peripheral Vessels. In: Topol, EJ, editor. Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 3rd ed. New York: Lippincott Williams &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Wilkins, 2007, p.1531-1537</ref>. These factors include smoking, dyslipedmia, dysglycemia, hypertension, family history of atherosclerotic vascular disease. In lower socioeconomic areas, PAD is more frequent as a result of increased incidence of smoking <ref name="Fowkes">Fowkes G. Peripheral vascular disease. 2010. http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-mds/haps/projects/HCNA/09HCNA3D2.pdf (accessed 9 May 2015)</ref>. Some studies report no difference in prevalence between the sexes <ref name="Mahameed " />, however, other studies have found a 3:1 ratio comparing men to women<ref name="Fowkes" /><ref name="Patient" />. A few studies have suggested that black non-Hispanics have an increased prevalence of PAD, with a reported 2.39 to 2.83 odd ratio. Although, a study that controlled for atherosclerotic risk factors found a small difference between whites and African Americans; 1.54 and 1.89, respectively<ref name="Collins">Collines, TC, Petersen, NJ, Suarez-Almazor, M, Ashton CM. Ethnicity and peripheral arterial disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005; 80(1): 48-54.</ref>. The majority of cases are asymptomatic..

| | Smoking increases the risk of developing PAD fourfold and has the greatest impact on disease severity. Compared to non-smokers, smokers with PAD have shorter life spans and progress more frequently to critical limb ischemia and amputation. Additional risk factors for PAD include diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, race, and ethnicity. |

|

| |

|

| == Aetiology == | | == Etiology == |

| | [[File:Diabetes-528678 960 720.jpg|right|frameless]] |

| | Peripheral artery disease is usually caused by atherosclerosis. Other causes may be inflammation of the blood vessels, injury, or radiation exposure.<ref name=":1" /> |

|

| |

|

| Atherosclerosis accounts for the majority of PAD, whereas uncommon vascular symptoms, such as vasculitis, thromboangiitis obliterans, popliteal entrapment syndrome, and fibromuscular dysplasis, account for less than 10% of cases <ref name="Mahameed" />. Atherosclerosis is the formation of lipid deposits in the tunica media and associated with damage to the endothelial lining <ref name="Martini">Martini, FH, Nath, JL, Bartholomew, EF. Fundamentals of anatomy and physiology. San Francisco: Pearson Education, 2015.</ref>.The endothelial cells become swollen with lipids and create a gap between in the linings. Platelets stick to the exposed collagen fibers, forming a localized clot that restricts arterial blood flow, leading to inadequate tissue perfusion. This and other complex interactions can lead to progression from asymptomatic PAD, Intermittent Claudication, Critical Limb Ischemia, Acute Limb Ischemia <ref name="Mahameed" />.<br>

| | Risk factors: Smoking, [[Hypertension]], [[Diabetes]], [[Hyperlipidemia|High cholesterol]], Increasing age (especially after reaching 50 years of age), Family history of peripheral artery disease, [[Coronary Artery Disease (CAD)|Heart disease]] or [[Stroke]], High levels of homocysteine (a protein component that helps build and maintain tissue).<ref name=":1" /> |

|

| |

|

| == Investigations == | | == History and Presentation == |

| | The most characteristic symptom of PAD is claudication which is a pain in the lower extremity muscles brought on by walking and relieved with rest. |

|

| |

|

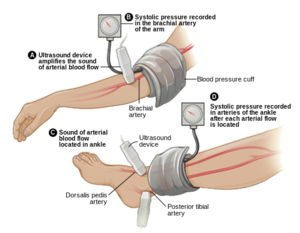

| A tool used to gain a diagnosis of PAD is Ankle Brachial Pressure Index (ABI), a simple and inexpensive test that measures the ratio between blood pressure in the legs to the blood pressure in the arms<ref name="Mahameed" />. The lower the pressure in the legs illustrates that PAD is present. An ABI of 0.9- 1.0 is normal, 0.70-0.89 is a mild disease, 0.40- 0.69 is a moderate disease, and less than .40 is a severe PAD<ref name="Mahameed" />. When measuring for ABI, make sure the patient is calm and in a rested position <ref name="NICE">NICE National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Lower limb peripheral arterial disease: diagnosis and management, 2012. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg147/chapter/guidance#management-of-intermittent-claudication (accessed 9 May 2015)</ref>. It is also important to assess individuals if they have diabetes, non-healing wounds on their legs and feet, unexplained pain in their peripherals, and check for femoral and popliteal pulses<ref name="NICE" />.<br><br>

| | * Although claudication has traditionally been described as cramping pain, some patients report leg fatigue, weakness, pressure, or aching. |

| | * Symptoms during walking occur in the muscle group one level distal to the artery narrowed or blocked by PAD. eg Patients with aortoiliac artery occlusive disease have symptoms in the thigh and buttock muscles, patients with femoropopliteal PAD have symptoms in their calf muscles. |

| | * Some patients with mild or moderate PAD rarely sustain a walking pace that increases the blood flow requirement of the lower extremity muscles. By being physically inactive, these patients avoid the supply-demand mismatch that triggers claudication symptoms. |

| | * Other patients with PAD have muscle discomfort when they walk but fail to report these symptoms because they attribute them to the natural consequences of aging. |

|

| |

|

| == Clinical Manifestations ==

| | Patients with severe PAD can develop ischemic rest pain. |

|

| |

|

| <ref name="NICE" /><br>non-healing wounds on legs or feet<br>unexplained leg pain<br>pain on walking that resolves when stopped<br>pain in foot at rest made which worsens with elevation<br>ulcers<br>gangrene<br>dry skin<br>cramping<br>aching

| | * These patients do not walk enough to claudicate because of their severe disease. |

| | * They complain of burning pain in the soles of their feet that is worse at night. They cannot sleep due to the pain and often dangle their lower leg over the side of the bed in an attempt to relieve their discomfort. The slight increase in blood flow due to gravity temporarily diminishes the otherwise intractable pain. |

|

| |

|

| == Physiotherapy and Other Management == | | === Clinical Manifestations === |

| | [[File:Arterial ulcer peripheral vascular disease.jpeg|right|frameless]]Image: A 71-year-old diabetic male smoker with severe peripheral arterial disease presented with a dorsal foot ulceration (2.5 cm X 2.4cm) that had been chronically open for nearly 2 years. |

|

| |

|

| One method of treating PAD is to reduce cardiovascular risk factors by quitting smoking, managing diabetes mellitus, treating dyslipidemia and hypertension <ref name="Mahameed" />. Another method is to treat PAD symptoms to improve quality of life through pharmacotherapy, exercise rehabilitation program, revascularization, thrombolysis and surgical procedures <ref name="Mahameed" />. The least invasive and most appropriate treatment conducted by Physiotherapists would be by prescribing an exercise program. The recommended parameters of physical exercise are a 6 month program of 30-35 minutes walking sessions at a frequency of 3-5 times a week at near-maximal pain tolerant <ref name="Mahameed" />. NICE recommends PAD patients to exercise at near-maximal pain for a total of 2 hours per week for 3 months to improve quality of life <ref name="NICE" />. <br>

| | * Non-healing wounds on legs or feet |

|

| |

|

| == Prevention ==

| | * Unexplained leg pain |

|

| |

|

| Brief consideration of how this pathology could be prevented and the physiotherapy role in health promotion in relation to prevention of disease or disease progression.

| | *Pain on walking that resolves when stopped |

| | *Pain in foot at rest made which worsens with elevation |

| | *[[Chronic Leg Ulcers|Ulcers]] |

| | *Gangrene |

| | *Dry skin |

| | *Cramping |

| | *Aching<ref name="NICE">NICE National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Lower limb peripheral arterial disease: diagnosis and management, 2012. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg147/chapter/guidance#management-of-intermittent-claudication (accessed 9 May 2015)</ref> |

|

| |

|

| == Resources <br> == | | == Evaluation == |

| | Making the diagnosis of PAD should factor in the patient’s history, physical exam, and objective test results. Key points in the history include an accurate assessment of: |

|

| |

|

| http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/peripheralarterialdisease/Pages/Introduction.aspx

| | * Patient’s walking ability<ref name=":1" />. For Objective Measures see below, under physiotherapy |

| | * [[File:Ankle-brachail index.png|right|frameless]]On physical exam, patients with PAD may have diminished or absent lower extremity pulses. This finding can be confirmed with the [[Ankle-Brachial Index|Ankle Brachial Pressure Index]] (ABI), a simple and inexpensive test that measures the ratio between blood pressure in the legs to the [[Blood Pressure|blood pressure]] in the arms.<ref name="Mahameed">Mahameed, AA, Bartholomew, JR, Disease of Peripheral Vessels. In: Topol, EJ, editor. Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 3rd ed. New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007, p.1531-1537</ref> An ABI of 0.9- 1.0 is '''normal''', 0.70-0.89 is a '''mild disease''', 0.40- 0.69 is a '''moderate disease''', and less than .40 is a '''severe PAD'''<ref name="Mahameed" />. When measuring for ABI, make sure the patient is calm and in a rested position <ref name="NICE" />. |

|

| |

|

| http://www.circulationfoundation.org.uk/help-advice/peripheral-arterial-disease/

| | * Other investigations include: |

| | ** Doppler US: initial investigation; assess flow and atherosclerotic plaque |

| | ** Angiography (CT, MR, DSA): direct imaging of the vessels and runoff.<ref name=":0" /> |

|

| |

|

| http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/peripheral-artery-disease/basics/definition/con-20028731

| | == Management == |

| | [[File:Dementia Walking Picture.jpg|right|frameless]] |

| | Management strategies for PAD attempt to achieve two distinct goals: lower cardiovascular risk and improve walking ability. All patients with PAD, regardless of the presence or absence of symptoms, have an increased risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, and thrombosis compared to patients without arterial disease. These cardiovascular events probably account for the shorter life expectancy of patients with PAD. Therefore, all patients diagnosed with PAD should undertake lifestyle changes aimed at lowering their cardiovascular risk profile. Key targets for lifestyle changes include quitting smoking, lowering cholesterol, and controlling hypertension and diabetes. |

|

| |

|

| == Recent Related Research (from [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ Pubmed]) ==

| | Other treatment involves: |

|

| |

|

| see tutorial on [[Adding PubMed Feed|Adding PubMed Feed]]

| | Medical therapy: involves the use of cilostazol, a medication that promotes vasodilation and suppresses the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells; the use of statins to improve the atherosclerotic disease; [[Pharmacological Management of Hypertension|antihypertensives]].<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":0" /> |

| <div class="researchbox"> | | [[File:3D Medical Animation Vascular Bypass Grafting.jpeg|right|frameless]] |

| <rss>addfeedhere|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10</rss> | | Revascularisation |

| </div>

| | |

| <?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

| | * Balloon angioplasty or stent placement provides a minimally invasive, percutaneous treatment option for patients with PAD symptoms that do not respond to exercise or medical therapy |

| <rss version="2.0">

| | * Surgical options for PAD include bypass grafts to divert flow around the blockage or endarterectomy to segmentally remove the obstructive plaque.<ref name=":1" /> |

| <channel>

| | |

| <title>pubmed: peripheral arterial ...</title>

| | === Physiotherapy Management === |

| <link>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Search&db=PubMed&term=peripheral%20arterial%20disease</link>

| | The least invasive and most appropriate treatment for PAD conducted by Physiotherapists would be by prescribing an exercise program. Exercise therapy involves walking until reaching pain tolerance, stopping for a brief rest, and walking again as soon as the pain resolves. These walking sessions should last 30 to 45 minutes, 3 to 4 times per week for at least 12 weeks. Despite being more effective, supervised exercise programs for PAD are not usually covered by insurance companies[[File:Treadmill walk.jpg|right|frameless]] |

| <description>NCBI: db=pubmed; Term=peripheral arterial disease</description>

| | A 2018 review of the best exercise prescription for PAD summarised their findings thus |

| <language>en-us</language>

| | * Supervised treadmill exercise improves treadmill walking performance in patients with PAD. |

| <docs>http://blogs.law.harvard.edu/tech/rss</docs>

| | * Supervised treadmill exercise has greater benefit on treadmill walking performance than home-based walking exercise. |

| <ttl>1440</ttl>

| | * Home-based walking exercise interventions that involve behavioral techniques are effective for functional impairment in people with PAD and improve the 6-min walk distance more than supervised treadmill exercise. |

| <image>

| | * Upper and lower extremity ergometry improve walking performance in patients with PAD and improve peak oxygen uptake. |

| <title>NCBI pubmed</title>

| | |

| <url>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query/static/gifs/iconsml.gif</url>

| | * Lower extremity resistance training can improve treadmill walking performance in PAD, but is not as effective as supervised treadmill exercise.<ref>McDermott MM. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5831500/ Exercise rehabilitation for peripheral artery disease: a review. Journal of cardiopulmonary rehabilitation and prevention]. 2018 Mar;38(2):63. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5831500/ (last accessed 6.9.2019)</ref> |

| <link>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez</link>

| | The optimal exercise program for PAD recommended by the American Heart Association states the following : '''Exercise Prescription for Supervised Exercise Treadmill Training in Patients With Claudication''' |

| <description>PubMed comprises more than 24 million citations for biomedical literature from MEDLINE, life science journals, and online books. Citations may include links to full-text content from PubMed Central and publisher web sites.</description>

| | # Modality Supervised Treadmill Walking |

| </image>

| | # Intensity 40%–60% maximal workload based on baseline treadmill test or workload that brings on claudication within 3–5 min during a 6-MWT |

| <item>

| | # Session duration 30–50 min of intermittent exercise; goal is to accumulate at least 30 min of walking exercise |

| <title>Time-dependent retinal ganglion cell loss, microglial activation and blood-retina-barrier tightness in an acute model of ocular hypertension.</title>

| | # Claudication intensity Moderate to moderate/severe claudication as tolerated |

| <link>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26001526?dopt=Abstract</link>

| | # Work-to-rest ratio Walking duration should be within 5–10 min to reach moderate to moderately severe claudication followed by rest until pain has dissipated (2–5 min) |

| <description>

| | # Frequency 3 times per week supervised |

| <![CDATA[<table border="0" width="100%"><tr><td align="left"/><td align="right"><a href="http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pubmed&cmd=Link&LinkName=pubmed_pubmed&from_uid=26001526">Related Articles</a></td></tr></table>

| | # Program duration At least 12 wk |

| <p><b>Time-dependent retinal ganglion cell loss, microglial activation and blood-retina-barrier tightness in an acute model of ocular hypertension.</b></p>

| | # Progression Every 1–2 wk: increase duration of training session to achieve 50 min. As individuals can walk beyond 10 min without reaching prescribed claudication level, manipulate grade or speed of exercise prescription to keep the walking bouts within 5–10 min |

| <p>Exp Eye Res. 2015 May 19;</p>

| | # Maintenance Lifelong maintenance at least 2 times per week |

| <p>Authors: Trost A, Motloch K, Bruckner D, Schroedl F, Bogner B, Kaser-Eichberger A, Runge C, Strohmaier C, Klein B, Aigner L, Reitsamer HA</p>

| | Based on currently available evidence. Exercise prescription should be individualized to each patient as tolerated. 6-MWT indicates 6-minute walk test. <ref>Diane Treat-Jacobson, Mary M. McDermott, Ulf G. Bronas et al.[https://ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000623 Optimal Exercise Programs for Patients With Peripheral Artery Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association.] AHA Journal Vol. Circulation.130 No.4 Available from: https://ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000623 (last accessed 7.9.2019)</ref> |

| <p>Abstract<br/>

| | |

| Glaucoma is a group of neurodegenerative diseases characterized by the progressive loss of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) and their axons, and is the second leading cause of blindness worldwide. Elevated intraocular pressure is a well known risk factor for the development of glaucomatous optic neuropathy and pharmacological or surgical lowering of intraocular pressure represents a standard procedure in glaucoma treatment. However, the treatment options are limited and although lowering of intraocular pressure impedes disease progression, glaucoma cannot be cured by the currently available therapy concepts. In an acute short-term ocular hypertension model in rat, we characterize RGC loss, but also microglial cell activation and vascular alterations of the retina at certain time points. The combination of these three parameters might facilitate a better evaluation of the disease progression, and could further serve as a new model to test novel treatment strategies at certain time points. Acute ocular hypertension (OHT) was induced by the injection of magnetic microbeads into the rat anterior chamber angle (n=22) with magnetic position control, leading to constant elevation of IOP. At certain time points post injection (4d, 7d, 10d, 14d and 21d), RGC loss, microglial activation, and microvascular pericyte (PC) coverage was analyzed using immunohistochemistry with corresponding specific markers (Brn3a, Iba1, NG2). Additionally, the tightness of the retinal vasculature was determined via injections of Texas Red labeled dextran (10 kDa) and subsequently analyzed for vascular leakage. For documentation, confocal laser-scanning microscopy was used, followed by cell counts, capillary length measurements and morphological and statistical analysis. The injection of magnetic microbeads led to a progressive loss of RGCs at the five time points investigated (20.07%, 29.52%, 41.80%, 61.40% and 76.57%). Microglial cells increased in number and displayed an activated morphology, as revealed by Iba1-positive cell number (150.23%, 175%, 429.25%,486.72% and 544.78%) and particle size analysis (205.49%, 203.37%, 412.84%, 333.37% and 299.77%) compared to contralateral control eyes. Pericyte coverage (NG2-positive PC/mm) displayed a significant reduction after 7d of OHT in central, and after 7d and 10d in peripheral retina. Despite these alterations, the tightness of the retinal vasculature remained unaltered at 14 and 21 days after OHT induction. While vascular tightness was unchanged in the course of OHT, a progressive loss of RGCs and activation of microglial cells was detected. Since a significant loss in RGCs was observed already at day 4 of experimental glaucoma, and since activated microglia peaked at day 10, we determined a time frame of 7 to 14 days after MB injection as potential optimum to study glaucoma mechanisms in this model.<br/>

| | A recent research study showed that Nordic walking training improved the gait pattern of patients with PAD remarkably and caused a significant increase in the absolute claudication distance and total gait distance. The combined training of Nordic walking with the isokinetic resistance training of the lower extremities muscles (NW + ISO) increased the amplitude of the general center of gravity oscillation to the greatest extent. However, only treadmill training had little effect on the gait pattern. Hence, Nordic walking can be used to rehabilitate patients with PAD as a form of gait training<ref>W Dziubek, M Stefańska, K Bulińska, K Barska [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32878323/ Journal of Clinical …, 2020 - mdpi.com]Effects of Physical Rehabilitation on Spatiotemporal Gait Parameters and Ground Reaction Forces of Patients with Intermittent Claudication |

| </p><p>PMID: 26001526 [PubMed - as supplied by publisher]</p>

| | </ref>. |

| ]]></description>

| | |

| <author> Trost A, Motloch K, Bruckner D, Schroedl F, Bogner B, Kaser-Eichberger A, Runge C, Strohmaier C, Klein B, Aigner L, Reitsamer HA</author>

| | == Outcome Measures == |

| <category>Exp Eye Res</category>

| | * [[Six Minute Walk Test / 6 Minute Walk Test|6 Minute Walk Test (MWT)]] |

| <guid isPermaLink="false">PubMed:26001526</guid>

| | * [[Timed Up and Go Test (TUG)|Timed Up and Go Test (TUG)]] |

| </item>

| | * EQ-5D |

| <item>

| | * Incremental shuttle walk test (ISWT)<ref>Dixit S, Chakravarthy K, Reddy RS, Tedla JS. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4513323/ Comparison of two walk tests in determining the claudication distance in patients suffering from peripheral arterial occlusive disease.] Advanced biomedical research. 2015;4.Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4513323/<nowiki/>(accessed 6.6.2021)</ref> |

| <title>Strategies for Free Flap Transfer and Revascularisation with Long-term Outcome in the Treatment of Large Diabetic Foot Lesions.</title>

| | |

| <link>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26001322?dopt=Abstract</link>

| | == Prevention == |

| <description>

| | According to Warren<ref name="Warren">Warren, E. Ten things the practice nurse can do about peripheral arterial disease. Practice Nurse 2013; 43; 12: 14-18.</ref> there are several methods one can prevent PAD. Firstly, help change the patient's lifestyle by educating them on the risk factors and the effects PAD. If the patient smokes cigarettes, it is important to address the issue and promote cessation. Those who consume a high fat diet have a higher chance of being diagnosed with PAD, thus one should encourage a reduced fat diet as a strong prevention method. Along with diet, it is important to live an active lifestyle. By being active and working up to the general standards of physical activity per week will allow a decrease in weight along with a decrease in risk of PAD. |

| <![CDATA[<table border="0" width="100%"><tr><td align="left"/><td align="right"><a href="http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pubmed&cmd=Link&LinkName=pubmed_pubmed&from_uid=26001322">Related Articles</a></td></tr></table>

| | |

| <p><b>Strategies for Free Flap Transfer and Revascularisation with Long-term Outcome in the Treatment of Large Diabetic Foot Lesions.</b></p>

| | == Prognosis == |

| <p>Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015 May 19;</p>

| | Even with treatment, the prognosis of PAD is generally guarded. If the patient does not change his/her lifestyle, the disease is progressive. In addition, most patients with PAD also have coexistence of cerebrovascular or coronary artery disease, which also increases the mortality rate. The outcomes in women tend to be worse than in men, chiefly because of the small diameter of the arteries. In addition, females are more likely to develop complications and embolic events.<ref name=":1" /> |

| <p>Authors: Kallio M, Vikatmaa P, Kantonen I, Lepäntalo M, Venermo M, Tukiainen E</p>

| | |

| <p>Abstract<br/>

| | == Conclusions == |

| OBJECTIVE/BACKGROUND: To analyse the impact of ischaemia and revascularisation strategies on the long-term outcome of patients undergoing free flap transfer (FFT) for large diabetic foot lesions penetrating to the tendon, bone, or joint.<br/>

| | Highlights from the 2016 AHA advice regarding PAD management |

| METHODS: Foot lesions of 63 patients with diabetes (median age 56 years; 70% male) were covered with a FTT in 1991-2003. Three groups were formed and followed until 2009: patients with a native in line artery to the ulcer area (n = 19; group A), patients with correctable ischaemia requiring vascular bypass (n = 32; group B), and patients with uncorrectable ischaemia lacking a recipient vessel in the ulcer area (n = 12; group C).<br/>

| | * Patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) should be on a program of guideline-directed medical therapy (including antiplatelet drugs that thin blood and statins to lower cholesterol) and should participate in a structured exercise program. |

| RESULTS: The respective 1, 5, and 10 year amputation free survival rates were 90%, 79%, and 63% in group A; 66%, 25%, and 18% in group B; and 50%, 42%, and 17%, in group C. The respective 1, 5, and 10 year leg salvage rates were 94%, 94%, and 87% in group A; 71%, 65%, and 65% in group B; and 50%, 50%, and 50% in group C. In 1 year, 43%, 45%, and 18% of the patients in groups A, B, and C, respectively, achieved stable epithelisation for at least 6 months. The overall amputation rate was associated with smoking (relative risk [RR] 3.09, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.8-5.3), heel ulceration (RR 2.25, 95% CI 1.1-4.7), nephropathy (RR 2.24, 95% CI 1.04-4.82), and an ulcer diameter of >10 cm (RR 2.08, 95% CI 1.03-4.48).<br/>

| |

| CONCLUSION: Despite diabetic comorbidities, complicated foot defects may be covered by means of an FFT with excellent long-term amputation free survival, provided that a patent native artery feeds the ulcer area. Ischaemic limbs may also be salvaged with combined FFT and vascular reconstruction in non-smokers and in the absence of very extensive heel ulcers. Occasionally, amputation is avoidable with FFT, even without the possibility of direct revascularisation.<br/>

| |

| </p><p>PMID: 26001322 [PubMed - as supplied by publisher]</p>

| |

| ]]></description>

| |

| <author> Kallio M, Vikatmaa P, Kantonen I, Lepäntalo M, Venermo M, Tukiainen E</author>

| |

| <category>Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg</category>

| |

| <guid isPermaLink="false">PubMed:26001322</guid>

| |

| </item>

| |

| <item>

| |

| <title>MR Angiography at 3 T of Peripheral Arterial Disease: A Randomized Prospective Comparison of Gadoterate Meglumine and Gadobutrol.</title>

| |

| <link>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26001243?dopt=Abstract</link>

| |

| <description>

| |

| <![CDATA[<table border="0" width="100%"><tr><td align="left"/><td align="right"><a href="http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pubmed&cmd=Link&LinkName=pubmed_pubmed&from_uid=26001243">Related Articles</a></td></tr></table>

| |

| <p><b>MR Angiography at 3 T of Peripheral Arterial Disease: A Randomized Prospective Comparison of Gadoterate Meglumine and Gadobutrol.</b></p>

| |

| <p>AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015 Jun;204(6):1311-1321</p>

| |

| <p>Authors: Loewe C, Arnaiz J, Krause D, Marti-Bonmati L, Haneder S, Kramer U, DALIA study group</p>

| |

| <p>Abstract<br/>

| |

| OBJECTIVE: This large-scale randomized study aimed to show the noninferiority in terms of diagnostic performance of gadoterate meglumine-enhanced versus gadobutrol-enhanced 3-T MR angiography (MRA) using digital subtraction angiography (DSA) as the reference standard in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD).<br/>

| |

| SUBJECTS AND METHODS: In this prospective international randomized double-blind phase IV trial, 189 patients were enrolled. Of them, 156 could be included in the per-protocol population for on-site assessments and 154 for off-site readings. Subjects underwent peripheral MRA, after injection of 0.1 mmol/kg of either gadoterate meglumine or gadobutrol, and DSA within 30 days. The diagnostic accuracy was evaluated and compared using a noninferiority analysis. Secondary endpoints included sensitivity, specificity, diagnostic confidence, contrast-to-noise ratio, and signal-to-noise ratio evaluations.<br/>

| |

| RESULTS: The percentage agreement between MRA and DSA for stenosis detection was similar for on-site readings for both groups (mean ± SD, 80.6% ± 16.1% with gadoterate meglumine vs 77.1% ± 19.6% with gadobutrol; 3.5% difference), and the same was true for off-site readings (73.9% ± 16.9% with gadoterate meglumine vs 75.1% ± 13.8% with gadobutrol; 1.1% difference). The noninferiority of gadoterate meglumine to gadobutrol was shown for both on- and off-site readings. Sensitivity in detecting significant stenosis (> 50%) was 72.3% for gadoterate meglumine versus 70.6% for gadobutrol, whereas specificity (92.6% vs 92.3%), diagnostic confidence (87.0% vs 86.0%), signal-to-noise ratio (165.5 vs 161.0), and contrast-to-noise ratio (159.5 vs 155.3) did not differ statistically significantly between the two groups.<br/>

| |

| CONCLUSION: Gadoterate meglumine was found to be not inferior to gadobutrol in terms of diagnostic performance in patients with PAOD undergoing 3-T contrast-enhanced MRA. No statistically significant differences were detected between the two MRA groups.<br/>

| |

| </p><p>PMID: 26001243 [PubMed - as supplied by publisher]</p>

| |

| ]]></description>

| |

| <author> Loewe C, Arnaiz J, Krause D, Marti-Bonmati L, Haneder S, Kramer U, DALIA study group</author>

| |

| <category>AJR Am J Roentgenol</category>

| |

| <guid isPermaLink="false">PubMed:26001243</guid>

| |

| </item>

| |

| <item>

| |

| <title>Links between Vitamin D Deficiency and Cardiovascular Diseases.</title>

| |

| <link>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26000280?dopt=Abstract</link>

| |

| <description>

| |

| <![CDATA[<table border="0" width="100%"><tr><td align="left"/><td align="right"><a href="http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pubmed&cmd=Link&LinkName=pubmed_pubmed&from_uid=26000280">Related Articles</a></td></tr></table>

| |

| <p><b>Links between Vitamin D Deficiency and Cardiovascular Diseases.</b></p>

| |

| <p>Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:109275</p>

| |

| <p>Authors: Mozos I, Marginean O</p>

| |

| <p>Abstract<br/>

| |

| The aim of the present paper was to review the most important mechanisms explaining the possible association of vitamin D deficiency and cardiovascular diseases, focusing on recent experimental and clinical data. Low vitamin D levels favor atherosclerosis enabling vascular inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, formation of foam cells, and proliferation of smooth muscle cells. The antihypertensive properties of vitamin D include suppression of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, renoprotective effects, direct effects on endothelial cells and calcium metabolism, inhibition of growth of vascular smooth muscle cells, prevention of secondary hyperparathyroidism, and beneficial effects on cardiovascular risk factors. Vitamin D is also involved in glycemic control, lipid metabolism, insulin secretion, and sensitivity, explaining the association between vitamin D deficiency and metabolic syndrome. Vitamin D deficit was associated in some studies with the number of affected coronary arteries, postinfarction complications, inflammatory cytokines and cardiac remodeling in patients with myocardial infarction, direct electromechanical effects and inflammation in atrial fibrillation, and neuroprotective effects in stroke. In peripheral arterial disease, vitamin D status was related to the decline of the functional performance, severity, atherosclerosis and inflammatory markers, arterial stiffness, vascular calcifications, and arterial aging. Vitamin D supplementation should further consider additional factors, such as phosphates, parathormone, renin, and fibroblast growth factor 23 levels.<br/>

| |

| </p><p>PMID: 26000280 [PubMed - as supplied by publisher]</p>

| |

| ]]></description>

| |

| <author> Mozos I, Marginean O</author>

| |

| <category>Biomed Res Int</category>

| |

| <guid isPermaLink="false">PubMed:26000280</guid>

| |

| </item>

| |

| <item>

| |

| <title>Emerging therapies for the treatment of ungual onychomycosis.</title>

| |

| <link>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25997365?dopt=Abstract</link>

| |

| <description>

| |

| <![CDATA[<table border="0" width="100%"><tr><td align="left"/><td align="right"><a href="http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pubmed&cmd=Link&LinkName=pubmed_pubmed&from_uid=25997365">Related Articles</a></td></tr></table>

| |

| <p><b>Emerging therapies for the treatment of ungual onychomycosis.</b></p>

| |

| <p>Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2015 May 22;:1-7</p>

| |

| <p>Authors: Kushwaha A, Murthy RN, Murthy SN, Elkeeb R, Hui X, Maibach HI</p>

| |

| <p>Abstract<br/>

| |

| INTRODUCTION: Onychomycosis, a common fungal infection in the finger and toe nails, affects approximately 2-8% of the worldwide population. Fungal infection is more complicated in those who suffer from conditions, such as diabetes, peripheral vascular diseases and compromised immune diseases. Area covered: Onychomycosis treatment has been classified on the basis of location of infection in the toes and fingers and infectious agents (dermatophytes fungi, yeast and non-dermatophyte molds). In this review, the available therapies (traditional and device based) and their limitations for the treatment of onychomycosis have been discussed. Expert opinion: The success rate with topical nail products has been minimal. The main reason for this poor success rate could be attributed to the lack of complete understanding of the pathophysiology of the disease and clinical pharmacokinetic data of drugs in the infected nail apparatus.<br/>

| |

| </p><p>PMID: 25997365 [PubMed - as supplied by publisher]</p>

| |

| ]]></description>

| |

| <author> Kushwaha A, Murthy RN, Murthy SN, Elkeeb R, Hui X, Maibach HI</author>

| |

| <category>Drug Dev Ind Pharm</category>

| |

| <guid isPermaLink="false">PubMed:25997365</guid>

| |

| </item>

| |

| <item>

| |

| <title>Adventitial layer enlargement correlates with the percentage of medial thickness in peripheral pulmonary arteries from patients with congenital heart defects.</title>

| |

| <link>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25991538?dopt=Abstract</link>

| |

| <description>

| |

| <![CDATA[<table border="0" width="100%"><tr><td align="left"/><td align="right"><a href="http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pubmed&cmd=Link&LinkName=pubmed_pubmed&from_uid=25991538">Related Articles</a></td></tr></table>

| |

| <p><b>Adventitial layer enlargement correlates with the percentage of medial thickness in peripheral pulmonary arteries from patients with congenital heart defects.</b></p>

| |

| <p>Cardiovasc Pathol. 1997 Jul;6(4):213-7</p>

| |

| <p>Authors: Aiello VD, Higuchi Mde L, Gutierrez PS, Ebaid M, Sesso A</p>

| |

| <p>Abstract<br/>

| |

| Arterial walls undergo modifications during the course of pulmonary hypertension, particularly in the medial and intimal layers, leading to progressive occlusion of the lumen. Adventitial layer enlargement has been described as being present in the experimental hypoxic model and in the persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. It was suggested that this enlargement may be related to stimulating factors derived from the medial smooth muscle cells. This study was designed to verify if different degrees of medial hypertrophy are correlated to the volume density of the adventitial layer in pulmonary hypertension secondary to congenital heart defects. Reviewing 21 lung biopsies from patients with congenital heart defects, we concluded that there is a statistically significant positive linear correlation between the mean percentage of medial arterial thickness and the volume density of the adventitial layer in the biopsies showing isolated medial hypertrophy. On the other hand, in biopsies showing frequent intimal proliferative lesions and irregular medial layer hypertrophy the correlation coefficient was lower. These findings suggest that the adventitial layer participates in the arterial remodeling process in secondary pulmonary hypertension, and that its enlargement depends on the qualitative degree of pulmonary vaso-occlusive disease. <br/>

| |

| </p><p>PMID: 25991538 [PubMed]</p>

| |

| ]]></description>

| |

| <author> Aiello VD, Higuchi Mde L, Gutierrez PS, Ebaid M, Sesso A</author>

| |

| <category>Cardiovasc Pathol</category>

| |

| <guid isPermaLink="false">PubMed:25991538</guid>

| |

| </item>

| |

| <item>

| |

| <title>Muramidase: A useful monocyte/macrophage immunocytochemical marker in swine, of special interest in experimental cardiovascular disease.</title>

| |

| <link>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25990995?dopt=Abstract</link>

| |

| <description>

| |

| <![CDATA[<table border="0" width="100%"><tr><td align="left"/><td align="right"><a href="http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pubmed&cmd=Link&LinkName=pubmed_pubmed&from_uid=25990995">Related Articles</a></td></tr></table>

| |

| <p><b>Muramidase: A useful monocyte/macrophage immunocytochemical marker in swine, of special interest in experimental cardiovascular disease.</b></p>

| |

| <p>Cardiovasc Pathol. 1994 Jul-Sep;3(3):183-9</p>

| |

| <p>Authors: Falk E, Fallon JT, Mailhac A, Fernandez-Ortiz A, Meyer BJ, Weng D, Shah PK, Badimon JJ, Fuster V</p>

| |

| <p>Abstract<br/>

| |

| The reliability of a rabbit polyclonal antibody against muramidase to identify monocytes/macrophages in swine was evaluated by immunostaining of cell smears and formaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections. Blood in tissue sections, cell smears (peripheral blood, buffy coat, and isolated mononuclear cells), and cultured mononuclear cells (adherent monocytes) contained positively stained cells with a morphology and in a number corresponding to that expected for a monocyte marker. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN), lymphocytes, and platelets were negative. In normal organs and tissues, mesenchymal cells with a distribution similar to that expected for macrophages were found to stain positively for muramidase. In pathologic tissues, positively stained inflammatory cells were identified in wounds, infected lungs, recently infarcted myocardium, and acute (variable numbers), organizing (often many), and healed (usually few) arterial thrombi. Enzymatic unmasking of antigenic determinants by trypsinization was necessary to achieve strong and consistent staining of monocytes/macrophages in tissue sections. A variety of epithelial cells of no differential diagnostic significance for monocyte/macrophage identification (e.g., renal proximal tubular cells) also stained positive for muramidase. The staining pattern of muramidase in swine corresponds to that described in humans, in whom muramidase has been shown to be a valuable marker of monocytes/macrophages. Swine PMN were, however, not stained or only weakly stained, whereas human PMN reportedly are strongly positive. As in humans, swine cardiac myocytes, smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, lymphocytes, and platelets were consistently negative. This antibody against muramidase is a useful immunohistochemical marker for swine monocytes/macrophages in formaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. <br/>

| |

| </p><p>PMID: 25990995 [PubMed]</p>

| |

| ]]></description>

| |

| <author> Falk E, Fallon JT, Mailhac A, Fernandez-Ortiz A, Meyer BJ, Weng D, Shah PK, Badimon JJ, Fuster V</author>

| |

| <category>Cardiovasc Pathol</category>

| |

| <guid isPermaLink="false">PubMed:25990995</guid>

| |

| </item>

| |

| <item>

| |

| <title>Persistently increased expression of the transforming growth factor-β1 gene in human vascular restenosis: Analysis of 62 patients with one or more episode of restenosis.</title>

| |

| <link>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25990773?dopt=Abstract</link>

| |

| <description>

| |

| <![CDATA[<table border="0" width="100%"><tr><td align="left"/><td align="right"><a href="http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pubmed&cmd=Link&LinkName=pubmed_pubmed&from_uid=25990773">Related Articles</a></td></tr></table>

| |

| <p><b>Persistently increased expression of the transforming growth factor-β1 gene in human vascular restenosis: Analysis of 62 patients with one or more episode of restenosis.</b></p>

| |

| <p>Cardiovasc Pathol. 1994 Jan-Mar;3(1):57-64</p>

| |

| <p>Authors: Nikol S, Weir L, Sullivan A, Sharaf B, White CJ, Zemel G, Hartzler G, Stack R, Leclerc G, Isner JM</p>

| |

| <p>Abstract<br/>

| |

| Transforming growth factor-beta-1 (TGF-β1) is a multifunctional cytokine with both growth-promoting and growth-inhibiting properties. Moreover, there is abundant evidence that TGF-β1 is the principal growth factor responsible for regulating proteoglycan synthesis in human blood vessels. To determine the potential contribution of TGF-β1 to restenosis, the current investigation sought to determine the time course of expression postangioplasty of the TGF-β1 gene. In situ hybridization was performed on tissue specimens obtained by directional atherectomy from 62 patients who had previously undergone angioplasty of native coronary or peripheral arteries and/or saphenous vein bypass grafts. The time interval between angioplasty and atherectomy was 1 hour to 25 months (M ± SEM = 5 ± 4 months) for all 62 patients, 5 ± 4 months for coronary arterial specimens, 8 ± 5 months for vein graft specimens, and 7 ± 3 months for peripheral arterial specimens. TGF-β1 mRNA expression remained persistently increased independent of the site from or time interval following which the specimen was obtained. For saphenous vein by pass grafts, TGF-β1 expression was highest in specimens retreived from patients with multiple versus single episodes of restenosis (16 ± 5 vs. 6 ± 5 grains/nucleus, p < 0.01). TGF-β1 expression did not correlate with patient age, sex, or known risk factors for coronary heart disease. The persistently augmented expression of TGF-β1 observed in the present series of restenosis lesions provides further support for the concept that TGF-β1 influences growth and development of restenosis plaque. <br/>

| |

| </p><p>PMID: 25990773 [PubMed]</p>

| |

| ]]></description>

| |

| <author> Nikol S, Weir L, Sullivan A, Sharaf B, White CJ, Zemel G, Hartzler G, Stack R, Leclerc G, Isner JM</author>

| |

| <category>Cardiovasc Pathol</category>

| |

| <guid isPermaLink="false">PubMed:25990773</guid>

| |

| </item>

| |

| <item>

| |

| <title>Vasculopathies of Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (von Recklinghausen Disease).</title>

| |

| <link>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25990068?dopt=Abstract</link>

| |

| <description>

| |

| <![CDATA[<table border="0" width="100%"><tr><td align="left"/><td align="right"><a href="http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pubmed&cmd=Link&LinkName=pubmed_pubmed&from_uid=25990068">Related Articles</a></td></tr></table>

| |

| <p><b>Vasculopathies of Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (von Recklinghausen Disease).</b></p>

| |

| <p>Cardiovasc Pathol. 1998 Mar-Apr;7(2):97-108</p>

| |

| <p>Authors: Lie JT</p>

| |

| <p>Abstract<br/>

| |

| Vasculopathies are the least publicized but most important manifestation of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1, or, von Recklinghausen disease) as the cause of morbidity and mortality in children and young adults afflicted with the disease. Occlusive or aneurysmal disease of arteries of all sizes may occur almost anywhere in the body. Coarctation or segmental hypoplasia of the abdominal aorta with or without renal artery ostial stenosis is a common cause of renovascular hypertension. Although rare, occlusive coronary artery disease in NF1 may result in myocardial infarction and sudden unexpected death. Visceral vasculopathy causes ischemic bowel disease; and catastrophic retroperitoneal or abdominal hemorrhage has been attributed to spontaneously ruptured arterial aneurysms. Peripheral vascular disease in NF1 with limb ischemia requiring an amputation is described for the first time here. Scanty information exists in the current pathology literature on NF1 vasculopathies, hence the presentation of this review. <br/>

| |

| </p><p>PMID: 25990068 [PubMed]</p>

| |

| ]]></description>

| |

| <author> Lie JT</author>

| |

| <category>Cardiovasc Pathol</category>

| |

| <guid isPermaLink="false">PubMed:25990068</guid>

| |

| </item>

| |

| <item>

| |

| <title>Multiple arterial injuries and prolonged cholesterol feeding do not increase percent lumen stenosis: impact of compensatory enlargement in the microswine model.</title>

| |

| <link>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25989958?dopt=Abstract</link>

| |

| <description>

| |

| <![CDATA[<table border="0" width="100%"><tr><td align="left"/><td align="right"><a href="http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pubmed&cmd=Link&LinkName=pubmed_pubmed&from_uid=25989958">Related Articles</a></td></tr></table>

| |

| <p><b>Multiple arterial injuries and prolonged cholesterol feeding do not increase percent lumen stenosis: impact of compensatory enlargement in the microswine model.</b></p>

| |

| <p>Cardiovasc Pathol. 1998 Jan-Feb;7(1):1-8</p>

| |

| <p>Authors: Thorpe PE, Zhan X, Agrawal DK, Hunter WJ, Farb A, Virmani R</p>

| |

| <p>Abstract<br/>

| |

| While the swine model is frequently utilized in the study of arterial intervention, it has been difficult to create severe peripheral arterial stenosis without total thrombotic occlusion with a single arterial injury and short-term cholesterol feeding. The combination of multiple arterial injuries and prolonged cholesterol feeding was explored in an effort to create lesions with significant luminal compromise. Nineteen microswine were divided into two groups and fed a high cholesterol diet followed by multiple balloon injuries of the iliac arteries. We conclude that repeated balloon injuries and longer cholesterol feeding significantly increase areas of plaque and necrotic core but do not increase percent stenosis because of arterial compensatory enlargement. The microswine iliac arteries enlarge in relation to plaque area and repeated balloon injuries. The compensatory lumen enlargement may be one of the factors resulting in significant angiographic underestimation of plaque area during the early stage of the atherosclerotic disease, but it may functionally delay important lumen stenosis until the lesion occupies 40% of the internal elastic lamina area. This study suggests that repeated injury and longer cholesterol feeding to increase percent stenosis may not be cost effective in this model. However, this model is good for studying an increase in plaque accumulation. <br/>

| |

| </p><p>PMID: 25989958 [PubMed]</p>

| |

| ]]></description>

| |

| <author> Thorpe PE, Zhan X, Agrawal DK, Hunter WJ, Farb A, Virmani R</author>

| |

| <category>Cardiovasc Pathol</category>

| |

| <guid isPermaLink="false">PubMed:25989958</guid>

| |

| </item>

| |

| <item>

| |

| <title>Correlation between Patient-Reported Symptoms and Ankle-Brachial Index after Revascularization for Peripheral Arterial Disease.</title>

| |

| <link>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25993299?dopt=Abstract</link>

| |

| <description>

| |

| <![CDATA[<table border="0" width="100%"><tr><td align="left"/><td align="right"><a href="http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pubmed&cmd=Link&LinkName=pubmed_pubmed&from_uid=25993299">Related Articles</a></td></tr></table>

| |

| <p><b>Correlation between Patient-Reported Symptoms and Ankle-Brachial Index after Revascularization for Peripheral Arterial Disease.</b></p>

| |

| <p>Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(5):11355-68</p>

| |

| <p>Authors: Je HG, Kim BH, Cho KI, Jang JS, Park YH, Spertus J</p>

| |

| <p>Abstract<br/>

| |

| Improvement in quality of life (QoL) is a primary treatment goal for patients with peripheral arterial disease (PAD). The current study aimed to quantify improvement in the health status of PAD patients following peripheral revascularization using the peripheral artery questionnaire (PAQ) and ankle-brachial index (ABI), and to evaluate possible correlation between the two methods. The PAQ and ABI were assessed in 149 symptomatic PAD patients before, and three months after peripheral revascularization. Mean PAQ summary scores improved significantly three months after revascularization (+49.3 ± 15 points, p < 0.001). PAQ scores relating to patient symptoms showed the largest improvement following revascularization. The smallest increases were seen in reported treatment satisfaction (all p's < 0.001). As expected the ABI of treated limbs showed significant improvement post-revascularization (p < 0.001). ABI after revascularization correlated with patient-reported changes in the physical function and QoL domains of the PAQ. Twenty-two percent of PAD patients were identified as having a poor response to revascularization (increase in ABI < 0.15). Interestingly, poor responders reported improvement in symptoms on the PAQ, although this was less marked than in patients with an increase in ABI > 0.15 following revascularization. In conclusion, data from the current study suggest a significant correlation between improvement in patient-reported outcomes assessed by PAQ and ABI in symptomatic PAD patients undergoing peripheral revascularization. <br/>

| |

| </p><p>PMID: 25993299 [PubMed - in process]</p>

| |

| ]]></description>

| |

| <author> Je HG, Kim BH, Cho KI, Jang JS, Park YH, Spertus J</author>

| |

| <category>Int J Mol Sci</category>

| |

| <guid isPermaLink="false">PubMed:25993299</guid>

| |

| </item>

| |

| <item>

| |

| <title>Influence of regular exercise on body fat and eating patterns of patients with intermittent claudication.</title>

| |

| <link>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25993298?dopt=Abstract</link>

| |

| <description>

| |

| <![CDATA[<table border="0" width="100%"><tr><td align="left"/><td align="right"><a href="http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pubmed&cmd=Link&LinkName=pubmed_pubmed&from_uid=25993298">Related Articles</a></td></tr></table>

| |

| <p><b>Influence of regular exercise on body fat and eating patterns of patients with intermittent claudication.</b></p>

| |

| <p>Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(5):11339-54</p>

| |

| <p>Authors: Leicht A, Crowther R, Golledge J</p>

| |

| <p>Abstract<br/>

| |

| This study examined the impact of regular supervised exercise on body fat, assessed via anthropometry, and eating patterns of peripheral arterial disease patients with intermittent claudication (IC). Body fat, eating patterns and walking ability were assessed in 11 healthy adults (Control) and age- and mass-matched IC patients undertaking usual care (n = 10; IC-Con) or supervised exercise (12-months; n = 10; IC-Ex). At entry, all groups exhibited similar body fat and eating patterns. Maximal walking ability was greatest for Control participants and similar for IC-Ex and IC-Con patients. Supervised exercise resulted in significantly greater improvements in maximal walking ability (IC-Ex 148%-170% vs. IC-Con 29%-52%) and smaller increases in body fat (IC-Ex -2.1%-1.4% vs. IC-Con 8.4%-10%). IC-Con patients exhibited significantly greater increases in body fat compared with Control at follow-up (8.4%-10% vs. -0.6%-1.4%). Eating patterns were similar for all groups at follow-up. The current study demonstrated that regular, supervised exercise significantly improved maximal walking ability and minimised increase in body fat amongst IC patients without changes in eating patterns. The study supports the use of supervised exercise to minimize cardiovascular risk amongst IC patients. Further studies are needed to examine the additional value of other lifestyle interventions such as diet modification. <br/>

| |

| </p><p>PMID: 25993298 [PubMed - in process]</p>

| |

| ]]></description>

| |

| <author> Leicht A, Crowther R, Golledge J</author>

| |

| <category>Int J Mol Sci</category>

| |

| <guid isPermaLink="false">PubMed:25993298</guid>

| |

| </item>

| |

| <item>

| |

| <title>Immunohistochemical analysis of paraoxonases and chemokines in arteries of patients with peripheral artery disease.</title>

| |

| <link>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25993297?dopt=Abstract</link>

| |

| <description>

| |

| <![CDATA[<table border="0" width="100%"><tr><td align="left"/><td align="right"><a href="http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pubmed&cmd=Link&LinkName=pubmed_pubmed&from_uid=25993297">Related Articles</a></td></tr></table>

| |

| <p><b>Immunohistochemical analysis of paraoxonases and chemokines in arteries of patients with peripheral artery disease.</b></p>

| |

| <p>Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(5):11323-38</p>

| |

| <p>Authors: Hernández-Aguilera A, Sepúlveda J, Rodríguez-Gallego E, Guirro M, García-Heredia A, Cabré N, Luciano-Mateo F, Fort-Gallifa I, Martín-Paredero V, Joven J, Camps J</p>

| |

| <p>Abstract<br/>

| |

| Oxidative damage to lipids and lipoproteins is implicated in the development of atherosclerotic vascular diseases, including peripheral artery disease (PAD). The paraoxonases (PON) are a group of antioxidant enzymes, termed PON1, PON2, and PON3 that protect lipoproteins and cells from peroxidation and, as such, may be involved in protection against the atherosclerosis process. PON1 inhibits the production of chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2) in endothelial cells incubated with oxidized lipoproteins. PON1 and CCL2 are ubiquitously distributed in tissues, and this suggests a joint localization and combined systemic effect. The aim of the present study has been to analyze the quantitative immunohistochemical localization of PON1, PON3, CCL2 and CCL2 receptors in a series of patients with severe PAD. Portions of femoral and/or popliteal arteries from 66 patients with PAD were obtained during surgical procedures for infra-inguinal limb revascularization. We used eight normal arteries from donors as controls. PON1 and PON3, CCL2 and the chemokine-binding protein 2, and Duffy antigen/chemokine receptor, were increased in PAD patients. There were no significant changes in C-C chemokine receptor type 2. Our findings suggest that paraoxonases and chemokines play an important role in the development and progression of atherosclerosis in peripheral artery disease. <br/>

| |

| </p><p>PMID: 25993297 [PubMed - in process]</p>

| |

| ]]></description>

| |

| <author> Hernández-Aguilera A, Sepúlveda J, Rodríguez-Gallego E, Guirro M, García-Heredia A, Cabré N, Luciano-Mateo F, Fort-Gallifa I, Martín-Paredero V, Joven J, Camps J</author>

| |

| <category>Int J Mol Sci</category>

| |

| <guid isPermaLink="false">PubMed:25993297</guid>

| |

| </item>

| |

| <item>

| |

| <title>Imaging of Small Animal Peripheral Artery Disease Models: Recent Advancements and Translational Potential.</title>

| |

| <link>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25993289?dopt=Abstract</link>

| |

| <description>

| |

| <![CDATA[<table border="0" width="100%"><tr><td align="left"/><td align="right"><a href="http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pubmed&cmd=Link&LinkName=pubmed_pubmed&from_uid=25993289">Related Articles</a></td></tr></table>

| |

| <p><b>Imaging of Small Animal Peripheral Artery Disease Models: Recent Advancements and Translational Potential.</b></p>

| |

| <p>Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(5):11131-11177</p>

| |

| <p>Authors: Lin JB, Phillips EH, Riggins TE, Sangha GS, Chakraborty S, Lee JY, Lycke RJ, Hernandez CL, Soepriatna AH, Thorne BR, Yrineo AA, Goergen CJ</p>

| |

| <p>Abstract<br/>

| |

| Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is a broad disorder encompassing multiple forms of arterial disease outside of the heart. As such, PAD development is a multifactorial process with a variety of manifestations. For example, aneurysms are pathological expansions of an artery that can lead to rupture, while ischemic atherosclerosis reduces blood flow, increasing the risk of claudication, poor wound healing, limb amputation, and stroke. Current PAD treatment is often ineffective or associated with serious risks, largely because these disorders are commonly undiagnosed or misdiagnosed. Active areas of research are focused on detecting and characterizing deleterious arterial changes at early stages using non-invasive imaging strategies, such as ultrasound, as well as emerging technologies like photoacoustic imaging. Earlier disease detection and characterization could improve interventional strategies, leading to better prognosis in PAD patients. While rodents are being used to investigate PAD pathophysiology, imaging of these animal models has been underutilized. This review focuses on structural and molecular information and disease progression revealed by recent imaging efforts of aortic, cerebral, and peripheral vascular disease models in mice, rats, and rabbits. Effective translation to humans involves better understanding of underlying PAD pathophysiology to develop novel therapeutics and apply non-invasive imaging techniques in the clinic.<br/>

| |

| </p><p>PMID: 25993289 [PubMed - as supplied by publisher]</p>

| |

| ]]></description>

| |

| <author> Lin JB, Phillips EH, Riggins TE, Sangha GS, Chakraborty S, Lee JY, Lycke RJ, Hernandez CL, Soepriatna AH, Thorne BR, Yrineo AA, Goergen CJ</author>

| |

| <category>Int J Mol Sci</category>

| |

| <guid isPermaLink="false">PubMed:25993289</guid>

| |

| </item>

| |

| <item>

| |

| <title>Endovascular stents and stent grafts in the treatment of cardiovascular disease.</title>

| |

| <link>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25992405?dopt=Abstract</link>

| |

| <description>

| |

| <![CDATA[<table border="0" width="100%"><tr><td align="left"><a href="http://openurl.ingenta.com/content/nlm?genre=article&issn=1550-7033&volume=10&issue=10&spage=2424&aulast=Sun"><img src="//www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/corehtml/query/egifs/http:--images.ingentaselect.com-images-linkout-ingentaconnect.gif" border="0"/></a> </td><td align="right"><a href="http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pubmed&cmd=Link&LinkName=pubmed_pubmed&from_uid=25992405">Related Articles</a></td></tr></table>

| |

| <p><b>Endovascular stents and stent grafts in the treatment of cardiovascular disease.</b></p>

| |

| <p>J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2014 Oct;10(10):2424-63</p>

| |

| <p>Authors: Sun Z</p>

| |

| <p>Abstract<br/>

| |

| Endovascular stents and stent grafts are increasingly used to treat a variety of cardiovascular diseases and these endovascular devices have gained popularity worldwide. The improvement of available endovascular devices is critical for the advancement of patient care in cardiovascular medicine. Problems are still associated with the endovascular treatments, many of which can adversely affect the treatment outcomes, such as the conversion of the patient to conventional open surgery, or resulting in procedure-related complications. This review aims to provide an overview of the commonly performed endovascular procedures including carotid artery stenting, coronary artery stenting, peripheral arterial stenting and endovascular stent grafting with regard to clinical outcomes and imaging assessment. A critical appraisal is given to the novel methods that have been recently developed to deal with these problems and future development of the endovascular devices is highlighted.<br/>

| |

| </p><p>PMID: 25992405 [PubMed - in process]</p>

| |

| ]]></description>

| |

| <author> Sun Z</author>

| |

| <category>J Biomed Nanotechnol</category>

| |

| <guid isPermaLink="false">PubMed:25992405</guid>

| |

| </item>

| |

|

| |

|

| </channel> | | * Restoring blood flow to the legs through vascular procedures is appropriate for many patients with severe symptoms due to PAD. |

| </rss> | | * Eliminating exposure to all tobacco – including second-hand smoke – is highly recommended for patients with PAD.<ref name=":3">Newsroom. [https://newsroom.heart.org/news/x-new-peripheral-artery-disease-guidelines-emphasize-medical-therapy-and-structured-exercise New peripheral artery disease guidelines emphasize medical therapy and structured exercise] 13.11. 2016 Available from: https://newsroom.heart.org/news/x-new-peripheral-artery-disease-guidelines-emphasize-medical-therapy-and-structured-exercise (last accessed 7.9.2019)</ref> |

|

| |

|

| == References == | | == References == |

|

| |

| see [[Adding References|adding references tutorial]].

| |

|

| |

|

| <references /> | | <references /> |

|

| |

|

| [[Category:Glasgow Caledonian University Project]] | | [[Category:Glasgow_Caledonian_University_Project]] |

| | [[Category:Cardiopulmonary]] |

| | [[Category:Cardiovascular Disease]] |

| | [[Category:Cardiovascular Disease - Conditions]] |

| | [[Category:Conditions]] |

| | [[Category:Non Communicable Diseases]] |