Sensory Integration

Original Editor - Based on a course by Nino Chumburidze

Top Contributors - Ewa Jaraczewska, Jess Bell, Tarina van der Stockt and Lauren Heydenrych

This article or area is currently under construction and may only be partially complete. Please come back soon to see the finished work! (24/04/2024)

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Sensory integration, or sensory processing, is the organisation of sensation for use.[1] It refers to the ability of our brain to recognise and respond to signals sent by our sensory system. Our senses include hearing, vision, smell, taste, touch, proprioception and interoception, and our vestibular system provides information about movement, changing head position and gravity.

Sensory integration plays an important role in a child's development, including their ability to develop and maintain social-emotional, motor, cognitive, adaptive, and other skills.[1] Children can be hypo- or hyper-sensitive to sensory inputs. When children have difficulty processing and responding to sensory information, their ability to participate in daily activities, school activities, etc, can be affected.

This article provides a brief overview of sensory integration and offers recommendations for sensory integration therapy for children with cerebral palsy when sensory processing challenges are present. Optionally, read Sensory Integration Therapy in Paediatric Rehabilitation to learn more about the development, conditions treated, and the role of the Occupational Therapist.

Senses[edit | edit source]

1. Touch / Tactile System[edit | edit source]

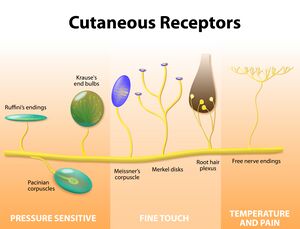

- Information is received from receptor cells in the skin

- Skin (cutaneous) receptors provide information about light touch, pressure, vibration, temperature, and pain

- Mechanoreceptors detect touch:[2][3][4]

- Hair follicles: affect touch perception

- Pacinian corpuscles: sense vibrations and enable discrimination between smooth and rough surfaces / textures

- Meissner corpuscles: sensitive to light touch, including a light tickle - they detect vibration and fine, discriminative touch[5]

- Merkel complexes: detect skin indentation and provide information on texture, curvature, and shape[6] - they are activated by the applied pressure and location of objects we interact with

- Ruffini corpuscles: detect stretch, as well as movement and finger position

- C-fibre low threshold mechanoreceptors (LTM) respond to “pleasant” and “effective” mechanical stimuli like gentle stroking and brushing and small changes in skin temperature[7]

Other receptors help detect temperature, taste, smell, etc:

- Chemoreceptors respond to changes in the concentration of chemicals in the body - they can detect tastes, smells and other internal changes, and they help regulate many systems, including cardiovascular and respiratory functions

- Thermoreceptors detect changes in temperature

2. Proprioception[edit | edit source]

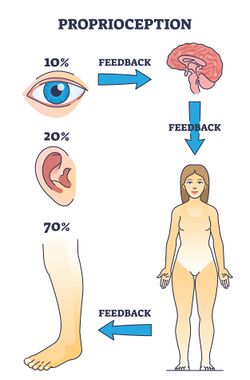

Proprioception (kinaesthesia) helps us to move. Proprioception refers to information arising from skin, muscles, joints, ligaments, and bones.[1] It allows us to perceive the location, movement, and actions of our body.[8]

- When we change position or move our limbs, the tissues (e.g. skin, muscle, tendons, etc) surrounding the moving joint are deformed[8]

- It has been suggested that muscle spindles "play the major role in kinaesthesia"[8]

- The skin receptors provide additional information[8]

- It is also suggested that Golgi tendon organs contribute to proprioception[8]

3. Vestibular System[edit | edit source]

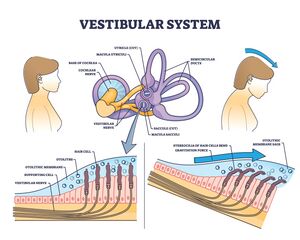

The vestibular system provides information about movement, gravity, and changing head position:[1]

- It tells us if we are moving or stationary

- It provides information about the direction and speed of our movements

- It helps to stabilise our eyes when we are moving

- It informs us if objects around us are moving or stationary

To learn more about the peripheral vestibular system, please click here.

4. Hearing / Auditory System[edit | edit source]

- The auditory system processes sound in the environment[1]

- Auditory receptors in the inner ear identify various sound stimuli (e.g. loud / soft, far / near)[1]

- These sound stimuli are then processed by the central nervous system to determine an appropriate response

- for example, in situations where safety is a concern (e.g. a fire alarm goes off), we recognise the sound and act accordingly)[1]

- Posture control can be influenced by sound frequency[9]

5. Visual System[edit | edit source]

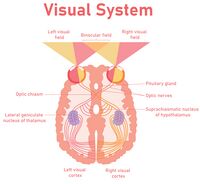

- Our visual system helps us see and perceive the environment around us[1]

- It identifies sights and understands what the eyes see[1]

- Visual inspection is also important in maintaining body balance as it helps position the body in space[10]

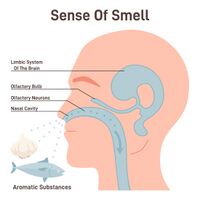

6. Smell / Olfactory System[edit | edit source]

- Our olfactory system allows us to distinguish various odours in the environment[1]

- It helps us to evaluate safety and identify safe or potentially dangerous situations (e.g. the smell of smoke)[1]

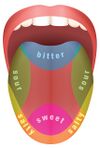

7. Taste / Gustatory System[edit | edit source]

- Our gustatory system distinguishes four tastes: sweet, sour, salty, and bitter[1]

- It allows us to identify desirable foods that are pleasant to us, as well as those that are potentially undesirable, such as a bitter dish[1]

8. Interoception[edit | edit source]

Interoception is "the sense involved in the detection of internal regulation, such as heart rate, respiration, hunger, and digestion".[11] Through interoception, we can distinguish our body's internal sensations.[12]

Sensory Integration[edit | edit source]

Sensory integration "is the potential to develop adequate motor and behavioural reactions to stimulus."[13] -- Ayres

The input from the senses is received, organised and interpreted to create a reaction appropriate to the stimuli received. This is called sensory processing.

Sensory Integration / Processing Challenges[edit | edit source]

Sensory integration dysfunction is a problem in the ability to ‘‘organise sensory information for use.’’[14] -- Ayres

Sensory function is essential for motor ability, social skills, and various behaviours. Disruption in modulation, discrimination or integration of sensory input can create a cascading effect that impacts all levels of sensory processing (motor, social, behavioural). This disruption can translate to problems with participation at home, school, and in the community.[11]

Sensory integration dysfunction may cause an individual to have difficulty with the following:[11]

- initiating or sustaining peer interactions

- developing relationships

- participating in activities of daily living

- regulating arousal behaviours

- language development

Sensory integration processing deficits may cause an individual to:[11]

- respond to stimulation more quickly

- respond to stimulation more intensely

- respond to stimulation for longer than individuals who do not have difficulty with sensory integration processing

Examples:[11]

- extreme responses to stimuli, including noise in a classroom, odours in a restaurant, the touch of clothing, or the movement of playground equipment

- "fight, flight or freeze" behavioural responses, such as aggression, withdrawal, or preoccupation with the expectation of sensory input

- severe difficulty forming and maintaining peer relationships

- extreme efforts to control events in the environment by over-reliance on routines

- behaviour regulation problems like temper tantrums, outbursts, hitting, kicking, biting, or spitting

- profound withdrawal from the group

- slow to respond to sensation, requiring "more intense stimuli to respond to the demands of the situation"[11]

Sensory Deficits and Cerebral Palsy[edit | edit source]

Children with cerebral palsy often have deficits in one or more sensory systems, including proprioception, tactile sensation, and visual perception.[1] They can also have impairments in processing and modulating mulstisensory information which then affects their activity level, muscle resistance, proprioception and emotional responses.[15]

This can affect their functional activities, especially bilateral arm activities, such as eating, playing, dressing, and showering.[16] A child with cerebral palsy and sensory processing difficulties might react to sensory stimuli in the following ways.

- Hyper-responsiveness to tactile input:[1]

- does not like to be touched

- avoids activities that involve getting messy

- resists light touch

- avoids certain types of clothing

- Hypo-responsiveness to tactile input:[1]

- lacks the ability to localise touch or respond when touched

- places items in their mouth

- may have a preference for activities or situations which involve brushing their hair, touching or hugging

- may fail to recognise when their hands or face are messy

- enjoys activities involving vibration

- Hyper-responsiveness to proprioceptive input:[1]

- cries when they are in weight-bearing positions or when their joints are moved

- chooses not to move or engage in activities

- Hypo-responsiveness to proprioceptive input:[1]

- bites or chews on non-food objects

- engages in pinching or hitting others or themself

- has difficulty changing body posture to match activity demands

- may have low, high, or variable muscle tone, which impacts the processing of proprioceptive information

- Hyper-responsiveness to vestibular input:[1]

- overreacts when moved in space

- becomes fearful of bouncing or swinging

- dislikes sudden or quick movements

- Hypo-responsiveness to vestibular input:[1]

- enjoys being moved and rocked passively

- seeks opportunities to fall without regard to safety

- likes excessive spinning, swinging, and active movements

Sensory Integration Therapy[edit | edit source]

Before incorporating Sensory Integration Therapy (SIT) into a rehabilitation plan, it is important to understand that there is a limited evidence base for SIT, "with few positive outcomes and some null or negative outcomes".[11] SIT is done by trained occupational therapists and physiotherapists depending on the country and training required.

SIT targets seven sensations: auditory, visual, gustatory (taste), olfactory (smell), somatosensory (proprioception and touch), vestibular, and interoception.[11] It is suggested that SIT directly improves attentional, emotional, motor, communication, and/or social difficulties.[17]

Goals:[1]

- To facilitate a child's daily functioning

- To elicit a child's adaptive response in the form of an appropriate reaction to environmental or situational requirements

General recommendations:[1]

- Establish clear goals

- Ensure the child's physical safety

- Prepare the child before starting an activity (safety, posture, muscle tone)

- Promote sensory-enriched activities when appropriate (reduce sensory input when needed)

- Collaborate with the child on activity choice and maximise the child's success

- Guide self-organisation and support optimal arousal

- Build a therapeutic alliance through positive and supportive relationships

- Provide a "just-right" challenge

- Determine the activity's intensity and duration

- Promote positive experiences and respect a child's preferences

- Integrate into daily routine (like chores and art)

- Incorporate every movement into play

Other considerations related to Cerebral Palsy and Sensory Integration Therapy:

- Occupational therapists[18]

- the most important focus should be the occupations that were identified by the child and family

- consider multiple hypotheses in the occupational analysis for the sensory difficulty

- make use of psychometrically sound outcome measures

- set specific and measurable goals focused on the occupations and participation levels

- involve the family and suggest changes to tasks and environment

- clearly explain the state of the evidence to the family, for an informed choice

- If the parents and therapists decide to use sensory integration therapy, they should establish clear, functional outcomes as the baseline before starting with therapy. This should be accompanied by parent, teacher and team member education. After 8-10 weeks the outcome measures should be completed again to determine if the intervention is effective.[18]

- A 2013 systematic review,[19] updated in 2020,[20] concluded that sensory integration is a "red light therapy" with regards to cerebral palsy and is considered and ineffective treatment. Therapists are advised to have open discussions with the family regarding "green light therapy" which has been shown to be effective and evidence-based.[19]

- It is important to note that since 2013, more research studies have been conducted regarding the assessment of sensory deficits and sensory integration therapy with children with cerebral palsy, especially as an adjunct to other conventional therapy.

- For instance a 2021 study showed that sensory integration therapy in combination with conventional physiotherapy exercises were more effective than just conventional therapy and exercises in improving gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy.[21]

Environment and Equipment[edit | edit source]

Every environment a child resides in is appropriate for SIT, including schools, homes, yards, and playgrounds. However, sensory rooms tend to be utilised most frequently for treatment. Ensuring a child's physical safety is essential. Clinicians must carefully observe a child's reactions and pay attention to signs the child is becoming overwhelmed. If the child does become overwhelmed, the clinician should take prompt action and proactively change the situation.[1]

Equipment: A sensory room should include at least three inventories of working materials for each sensation:[1]

- tactile: sand, foam, various textures[1]

- proprioception: ball pool / pit, therapy ball, heavy blanket[1]

- vestibular: platform swing, bolster swing, net swing, tilt board, trampoline, ramp[22]

- hearing: water (fountains, faucets, waves, and waterfalls), music (radio, instruments, chimes), instruments (drums, piano, guitar, keyboards and tambourines)[23]

- visual: neon, patterned and florescent papers, coloured, strung, flashing, holiday and strobe lights, wind socks, wind-up toys, activity boxes and age-appropriate mobiles[23]

- smell: air fresheners (lavender, potpourri and sachets), candles, lotions, powders, perfumes, flowers, plants, breads, cookies, stews, bacon, onions[23]

- taste: fruits, milk-based items, hot and cold items, candies, cheese[23]

Activities[edit | edit source]

The following activities are examples of how elements of sensory integration can be used to help treat sensory deficits depending on the sensory profile of the child:

1. Tactile Activities[edit | edit source]

- Functional play with a sensory board and different tactile materials

- Playing with different brushes, drawing with soap crayons or chalk on the body, and erasing with various textures[1]

- Engaging in different play activities with Play-Doh, like hiding small objects in the Play-Doh or creating a tactile bin for finger exploration[1]

- Exploring kitchen activities, such as mixing, tasting, smelling, and washing vegetables[1]

- Preparing a tactile bag (i.e. using a zipper bag filled with conditioner cream and food colours with small beans or toys hidden inside)[1]

- Creating sensory balloons (e.g. balloons filled up with materials like cereals, flowers, sand, etc)[1]

- Making a tactile board using a piece of wood, tissue, and different materials[1]

2. Proprioceptive Activities[edit | edit source]

- Engaging in playground activities[1]

- Participating in gross motor activities[1]

- Encouraging imitations of various movements[1]

- Weight-bearing activities, such as crawling and push-ups[1]

- Resistance activities like pushing and pulling[1]

3. Vestibular Stimulation Activities[edit | edit source]

- Spinning, rocking, climbing, sliding, riding toys, walking, running[1]

- Standing on one foot, progressing to standing on one foot with eyes closed[23]

- Throwing a ball[23]

- Shaking head or turning head from left to right at a rapid pace[23]

- Bouncing on a bed, ball or parent’s knees[23]

- Swinging in a blanket, swing, or on a rope[23]

Resources[edit | edit source]

- What is Sensory Integration?

- Warutkar VB, Krishna Kovela R. Review of Sensory Integration Therapy for Children With Cerebral Palsy. Cureus. 2022 Oct 26;14(10):e30714.

- Case-Smith J, Weaver LL, Fristad MA. A systematic review of sensory processing interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2015 Feb;19(2):133-48.

- Awalludin, ZA. Sensory Integration and Functional Movement: A Guide to Optimal Development in Early Childhood. 4th International Conference on Arts Language and Culture (ICALC 2019)

- Tracking Sensory Development

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 1.31 1.32 1.33 1.34 1.35 1.36 1.37 Chumburidze N. Sensory Integration. Plus Course 2024

- ↑ Marzvanyan A, Alhawaj AF. Physiology, Sensory Receptors. [Updated 2023 Aug 14]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539861/

- ↑ Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, et al., editors. Neuroscience. 2nd edition. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; 2001. Mechanoreceptors Specialized to Receive Tactile Information. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10895/

- ↑ Iheanacho F, Vellipuram AR. Physiology, Mechanoreceptors. [Updated 2023 Sep 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541068/

- ↑ Piccinin MA, Miao JH, Schwartz J. Histology, Meissner Corpuscle. [Updated 2023 Mar 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK518980/

- ↑ Bataille-Savattier A, Le Gall-Ianotto C, Lebonvallet N, Misery L, Talagas M. Do Merkel complexes initiate mechanical itch? Exp Dermatol. 2023 Feb;32(2):226-234.

- ↑ Huzard D, Martin M, Maingret F, Chemin J, Jeanneteau F, Mery PF, Fossat P, Bourinet E, François A. The impact of C-tactile low-threshold mechanoreceptors on affective touch and social interactions in mice. Sci Adv. 2022 Jul;8(26):eabo7566.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Proske U, Gandevia SC. The proprioceptive senses: their roles in signalling body shape, body position and movement, and muscle force. Physiol Rev. 2012 Oct;92(4):1651-97.

- ↑ Siedlecka B, Sobera M, Sikora A, Drzewowska I. The influence of sounds on posture control. Acta of Bioengineering and Biomechanics 2015;17(3):95-102.

- ↑ Pankanin E. Visual control is important in maintaining the body's balance. Journal of Education, Health and Sport. 2018;8(8):381-387.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 Camarata S, Miller LJ, Wallace MT. Evaluating Sensory Integration/Sensory Processing Treatment: Issues and Analysis. Front Integr Neurosci. 2020 Nov 26;14:556660.

- ↑ Sensory. Available from https://pathways.org/topics-of-development/sensory/ [last access 13.02.2024]

- ↑ Ayres A. J. (1972). Sensory Integration and Learning Disorders. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.

- ↑ Ayres AJ. The development of perceptual-motor abilities: a theoretic basis for treatment of dysfunction. Am J Occup Ther. 1963 Nov-Dec;17:221-5.

- ↑ Pavão SL, Rocha NA. Sensory processing disorders in children with cerebral palsy. Infant Behavior and Development. 2017 Feb 1;46:1-6.

- ↑ Erkek S, Çekmece Ç. Investigation of the Relationship between Sensory-Processing Skills and Motor Functions in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Children. 2023; 10(11):1723.

- ↑ Miller LJ, Fuller DA, Roetenberg J. Sensational Kids: Hope and Help for Children With Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD). New York, NY: Penguin, 2014.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Pollock N. Sensory integration: A review of the current state of the evidence. Occupational therapy now. 2009;11(5):6-10.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Novak I, Mcintyre S, Morgan C, Campbell L, Dark L, Morton N, Stumbles E, Wilson SA, Goldsmith S. A systematic review of interventions for children with cerebral palsy: state of the evidence. Developmental medicine & child neurology. 2013 Oct;55(10):885-910.

- ↑ Novak I, Morgan C, Fahey M, Finch-Edmondson M, Galea C, Hines A, et al. State of the evidence traffic lights 2019: systematic review of interventions for preventing and treating children with cerebral palsy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2020 Feb 21;20(2):3.

- ↑ Mahaseth PK, Choudhary A. Sensory integration therapy verses conventional physical therapy among children with cerebral palsy on gross motor function–a comparative randomized controlled trial. Annals of the Romanian Society for Cell Biology. 2021 Apr 30:17315-34.

- ↑ Rassafiani M, Akbarfaimi N, Hosseini SA, Shahshahani S, Karimlou M, Tabatabai Ghomsheh F. The Effect of the combination of active vestibular interventions and occupational therapy on Balance in Children with Bilateral Spastic Cerebral Palsy: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Iran J Child Neurol. 2020 Fall;14(4):29-42.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 23.7 23.8 Sensory Integration. Available from https://www.cerebralpalsy.org/about-cerebral-palsy/treatment/therapy/sensory-integration-therapy [last access 13.02.2024]