Evidence Based Practice (EBP)

Original Editor - Rachael Lowe

Top Contributors - Rachael Lowe, Admin, Scott Buxton, Mariam Hashem, WikiSysop, Sai Kripa, Tyler Shultz, Sheik Abdul Khadir, Michelle Lee and Cindy John-Chu

What is EBP?[edit | edit source]

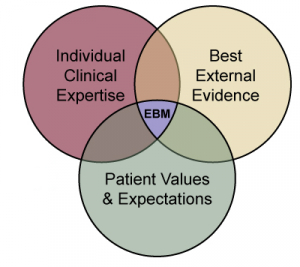

Evidence based practice (EBP) is 'the integration of best research evidence with best available scientific research, clinical expertise and patient values'[1] which when applied by practitioners will ultimately lead to improved patient outcome.

These three types of evidence—scientific research, clinical expertise, and patient values and circumstances form the basis on which you and your patients will decide on the best physical therapy treatment plan in any given situation. If you are an evidence-based therapist, you will base your decisions on these three types of evidence. The aim of evidence-based therapists is to make sure that patient care is informed by the greatest available research in order to maximize the benefits that patients receive from therapy. EBP provides a structured method for thinking about and collecting the different types of evidence used to make clinical decisions.[2]

In the original model there are three fundamental components of evidence based practice.

- best evidence which is usually found in clinically relevant research that has been conducted using sound methodology

- clinical expertise refers to the clinician's cumulated education, experience and clinical skills

- patient values which are the unique preferences, concerns and expectations each patient brings to a clinical encounter.

It is the integration of these three components that defines a clinical decision evidence-based. This integration can be effectively achieved by carrying out the five following steps of evidence based practice.[1]

Evidence can be thought of as coming from three different sources:

1.Scientific research

2.Clinical expertise

3.Patient values and circumstances

Scientific research-The scientific research evidence is empirical evidence acquired through systematic testing of a hypothesis. When explaining research evidence with a patient, it's crucial to speak in simple language and follow up with questions to make sure the patient comprehends. Therapists have the primary responsibility to identify, evaluate, and summarize research evidence concerning a patient’s care.

Clinical expertise-It refers to implicit and explicit knowledge about physical therapy diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and prognosis gained from cumulative years of caring for patients with disease and injury and working to improve and refine that care.

Patient Values and Circumstances-The patient and his or her caregivers create the most important pillar of evidence to the decision-making process. Evidence from the patient can be divided into two categories: values and circumstances. Patient values include the beliefs, preferences, expectations, and cultural identification that the patient brings to the therapy environment. Fundamentally, values are the core principles that guide a person’s life and life choices.[2]

The 5 Steps[edit | edit source]

1. Formulate an answerable question

One of the fundamental skills required for EBP is the asking of well-built clinical questions. By formulating an answerable question you are able to focus your efforts specifically on what matters. These questions are usually triggered by patient encounters which generate questions about the diagnosis, therapy, prognosis or aetiology.

2. Find the best available evidence

The second step is to find the relevant evidence. This step involves identifying search terms which will be found in your carefully constructed question from step one; selecting resources in which to perform your search such as PubMed and Cochrane Library; and formulating an effective search strategy using a combination of MESH terms and limitations of the results.

It is important to be skilled in critical appraisal so that you can further filter out studies that may seem interesting but are weak. Use a simple critical appraisal method that will answer these questions: What question did the study address? Were the methods valid? What are the results? How do the results apply to your practice?

Individual clinical decisions can then be made by combining the best available evidence with your clinical expertise and your patients values. These clinical decisions should then be implemented into your practice which can then be justified as evidence based.

The final step in the process is to evaluate the effectiveness and efficacy of your decision in direct relation to your patient. Was the application of the new information effective? Should this new information continue to be applied to practice? How could any of the 5 processes involved in the clinical decision making process be improved the next time a question is asked?

These steps may be more memorable if remembered as[3]:

- Ask

- Acquire

- Appraise

- Apply

- Audit

In 2010 Melnyk et al[4] proposed adding 2 other steps to the process:

Step 0: Cultivate a spirit of inquiry - without this spirit of inquiry the next steps of the EBP process are not likely to happen.

Step 6: Disseminate EBP results - Clinicians can achieve wonderful outcomes for their patients through EBP, but they often fail to share their experiences with colleagues and their own or other health care organisations. This leads to needless duplication of effort, and perpetuates clinical approaches that are not evidence based. Among ways to disseminate successful initiatives are EBP rounds in your institution, presentations at local, regional, and national conferences, reports in peer-reviewed journals or professional newsletters and publications for general audiences and writing findings in Physiopedia!!

The Problem with EBP[5][edit | edit source]

- The evidence based “quality mark” has been misappropriated by vested interests

- The volume of evidence, especially clinical guidelines, has become unmanageable

- Statistically significant benefits may be marginal in clinical practice

- Inflexible rules and technology driven prompts may produce care that is management driven rather than patient centred

- Evidence based guidelines often map poorly to complex multimorbidity

Implementation Strategies for Evidence Based Practice[edit | edit source]

The Implementation Strategies for Evidence-Based Practice guide is set to help health care professionals who are in responsibility for EBP choose implementation tactics that would make it easier for clinicians and practice teams to incorporate clinical practice recommendations into standard operating procedures. Strategies are selected and positioned to enhance the movement through 4 phases of implementation: creating awareness and interest, building knowledge and commitment, promoting action and adoption, and pursuing integration and sustainability. [6]

Presentations[edit | edit source]

| Evaluating Evidence Based Practice: Does EBP Facilitate Wise Clinical Decisions

This is a talk by LJ Lee and Roger Kerry, who are both physiotherapists. This talk was presented as a Focused Symposium at the International Federation of Orthopaedic Manipulative Physical Therapists (IFOMPT) 2012 conference in Quebec City, Canada on 4th October 2012. LJ and Roger explore and challenge the notion of evidence based practice (EBP) since its introduction into health care over 20 years ago. The evidence for EBP is investigated, and the role of clinical experience and expertise is analysed. |

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Evidence-Based Practice: An Interprofessional Tutorial from University of Minnosota Library

- Evidence based practice education resources from WCPT

- This short overview article by World Confederation of Physical Therapy (WCPT) addresses the issue of EBP.

- EBP Tools from CEBM

- EBM Toolkit from University of Alberta

- Cleland JA, Noteboom JT, Whitman JM, Allison SC (2008) A primer on selected aspects of evidence-based practice relating to questions of treatment, part 1: asking questions, finding evidence, and determining validity, J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008 Aug;38(8):476-84

- Noteboom JT, Allison SC, Cleland JA, Whitman JM (2008) A primer on selected aspects of evidence-based practice to questions of treatment, part 2: interpreting results, application to clinical practice, and self-evaluation, J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008 Aug;38(8):485-501

A series of eight articles on Getting Research Findings into Practice published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ):

- Making better use of research findings. Andy Haines and Anna Donald. BMJ. 1998 Jul 4; 317(7150): 72–75.

- When to act on the evidence. Trevor Sheldon, Gordon Guyatt and Andy Haines. BMJ. 1998 Jul 11; 317(7151): 139–142

- Finding information on clinical effectiveness. Julie Glanville, Margaret Haines, and Ione Auston. BMJ. 1998 Jul 18; 317(7152): 200–203.

- Barriers and bridges to evidence based clinical practice. Brian Haynes and Andy Haines. BMJ. 1998 Jul 25; 317(7153): 273–276.

- Using research findings in clinical practice. Sharon Straus and Dave Sackett. BMJ. 1998 Aug 1; 317(7154): 339–342.

- Decision analysis and the implementation of research findings. R J Lilford, S G Pauker, D A Braunholtz, and Jiri Chard.BMJ. 1998 Aug 8; 317(7155): 405–409

- Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. Lisa A Bero, Roberto Grilli, Jeremy M Grimshaw, Emma Harvey, Andrew D Oxman, and Mary Ann Thomson. BMJ. 1998 Aug 15; 317(7156): 465–468.

- Implementing research findings in developing countries. Paul Garner, Rajendra Kale, Rumona Dickson, Tony Dans, and Rodrigo Salinas. BMJ. 1998 Aug 22; 317(7157): 531–535.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray JAM, Haynes RB, Richardson WS: Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 1996;312:71-2

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Linda Fetters. Evidence Based Physical Therapy. 2nd Edition. F A Davis, 2018

- ↑ EBP Process. Accessed at https://www.eboptometry.com/content/optometry/ebp-resource/practitioners-students-teachers/ebp-process-0 on 25 March 2015

- ↑ Bernadette Mazurek Melnyk, Ellen Fineout-Overholt, Susan B. Stillwell, Kathleen M.Williamson. The Seven Steps of Evidence-Based Practice. AJN, 2010,110(1)

- ↑ Trisha Greenhalgh, Jeremy Howick, and Neal Maskrey. Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis? BMJ. 2014; 348: g3725.

- ↑ Cullen L, Adams SL. Planning for implementation of evidence-based practice. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2012 Apr 1;42(4):222-30.