Wheelchair Assessment - Assessment Interview

Original Editor - Naomi O'Reilly as part of the Wheelchair Service Provision Content Development Project

Top Contributors - Naomi O'Reilly, Kim Jackson, Rucha Gadgil, Samuel Adedigba, Amrita Patro and Olajumoke Ogunleye

Introduction[edit | edit source]

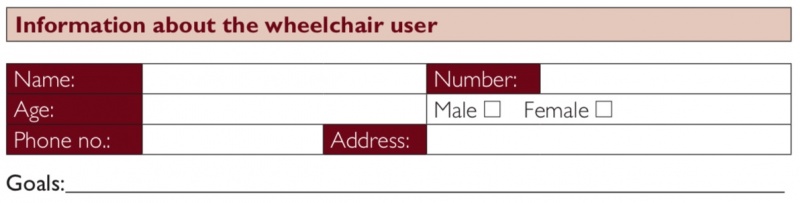

The first part of the assessment is the assessment interview. During this part of the assessment the wheelchair service personnel gather information about the wheelchair user, which will help to identify the most appropriate wheelchair for the wheelchair user. The assessment interview components at both basic and intermediate level include information about the wheelchair user, their physical condition, their lifestyle and environment and also examines their existing wheelchair, if applicable. Even though the assessment interview components at basic and intermediate levels are very similar, more information is gathered at intermediate level about the wheelchair user’s diagnosis and any physical issues in order to determine the requirements for additional postural support devices. During the assessment interview information from four areas is collected. Questions do not need to be asked in the order given on the form. sometimes wheelchair users will volunteer information before they are asked, or it may be more natural to ask questions in a different order. [1]

Information about the Wheelchair User[edit | edit source]

The ‘information about the wheelchair user’ part of the wheelchair assessment form has an administrative purpose and ensures that the wheelchair service has the wheelchair user’s basic personal and contact information so that the wheelchair user can be contacted for the follow up in the future. They also give statistical information about the users seen by the service. Goals for the individual is vital to understand what the wheelchair user expects from their wheelchair. [1]

Wheelchair service personnel should also record here what the wheelchair user’s goals are for a new or improved wheelchair. The word ‘goal’ may not be familiar to a wheelchair user. It is up to the wheelchair service personnel to ask questions to find out what the wheelchair user’s goal or goals are. The following are examples of possible questions wheelchair service personnel may ask to find out what the wheelchair user’s goal or goals are:

- Why did you come to the wheelchair service today?

- What should your wheelchair help you do?

The following are examples of possible goals:

- I need to be able to reach the well to collect water.

- I need to be able to get into a lift to reach my apartment.

- I need to be able to get my wheelchair into a small car.

- I would like to be more comfortable when sitting.

- I would like to be able to sit for longer in my wheelchair before I get tired.

- I need to be able to get in and out of the wheelchair myself.

- I need to be able to sit at a desk to use the computer.

- I would like to be able to visit my family and need a wheelchair that I can take on the bus.

Physical Condition[edit | edit source]

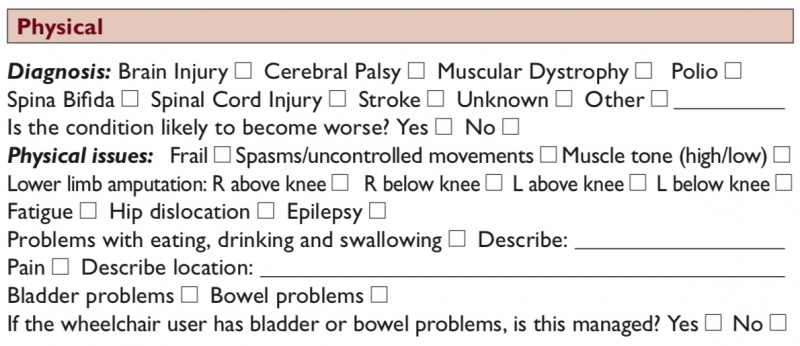

The ‘diagnosis / physical issues’ part of the wheelchair assessment form is important because some of the features of different diagnosis and physical issues, covered in Wheelchair Users, can affect the choice of wheelchair and additional postural supports. Sometimes the wheelchair user may not know the name of their diagnosis or condition. It is also possible that no diagnosis has been made. In this case identify any specific physical issues and continue the assessment. Some physical issues that wheelchair users may experience can have a direct impact on choosing the most appropriate wheelchair. [1]

Spasticity[edit | edit source]

The most well-known and referenced description of spasticity is the physiological definition proposed by Lance (1980): 'Spasticity is a motor disorder characterised by a velocity-dependent increase in tonic stretch reflexes (muscle tone) with exaggerated tendon jerks, resulting from hyperexcitability of the stretch reflex, as one component of the upper motor neurone syndrome'. [2]

More recently, a definition from Pandyan et al (2005) states that spasticity is: 'Disordered sensorimotor control, resulting from an upper motor neuron lesion (UMN), presenting as an intermittent or sustained involuntary activations of muscles'. [3]

Some wheelchair users may have problems with spasticity, which can be triggered in a number of different ways including; the position of the person’s hip, knee and ankle; touch and movement of the wheelchair, particularly over rough/bumpy ground.

Considerations for Wheelchair Provision[edit | edit source]

Find out how the spasticity or uncontrolled movements affect the wheelchair user and problem solve with them in order to develop a wheelchair set up for them that can counteract the affects. Straps may be useful give a wheelchair user increased control over their legs and feet. Straps may be used over the feet to keep the feet on the footrest or at the knees to keep the legs together. Ensure any straps used are fastened with velcro so that it will release if the wheelchair user falls out of the wheelchair.

Other supports or adjustments that can be made to cater for spasticity or uncontrolled movements include increased support around the pelvis to support a neutral posture, adjusting the wheelchair seat to backrest angle so that the wheelchair user sits with their hips bent slightly higher than neutral (increased 'dump') an positioning the footrests so that the knees are bent slightly more than 90 degrees, ‘tucking’ the feet in or trying different angles of footrests.

If the spasticity or uncontrolled movements are very strong, consider using a solid seat and backrest support, selecting a wheelchair with an adjustable rear wheels position to make the wheelchair less tippy and therefore more stable and provision of an anti-tip bar to stop the wheelchair from tipping over backwards which is especially important in those who have strong extension spasticity patterns. [1]

Altered Muscle Tone[edit | edit source]

Muscle tone is the resistance of muscles to passive stretch or elongation, which is effectively the amount of tension a muscle has at rest. Normal tone should be high enough to resist the effects of gravity in both posture and movement, yet low enough to allow freedom of movement, allowing the limb or joint to be moved freely and easily. [4] However some people may have muscle tone that is too high or too low, which can have an impact on both posture and movement. Problems with muscle tone can be a problem for some wheelchair users and is a common problem for people who have cerebral palsy [5], brain injury [6], spinal cord injury [7], and stroke [8][4].High Tone; There is more resistance/tension, so it is harder to move a limb or joint. [5] A person with high muscle tone will usually find it difficult to move the affected limb or joint, and movement may be slow. Some people with high tone can move only in a certain ‘fixed’ pattern. [6] If the muscle tone is very high, almost no movement is possible.

Low Tone; There is less resistance, so it is easy to passively move the limb or joint. However, a person with a low muscle tone may find it difficult to initiate movement, and may also find controlling their movement difficult. Low muscle tone is sometimes described as ‘floppy or flaccid’. If the tone is very low, it may be very difficult for the person to move.[5]

Common Characteristics that may affect Wheelchair Provision with Altered Tone[edit | edit source]

The affect of altered muscle tone on the wheelchair user depends on the severity of the alteration in muscle tone, and the muscles that are affected. Some impairments that can result from altered muscle tone include [5][6][9]

- reduced balance;

- difficulty sitting upright and comfortably;

- reduced muscle control, which can affect how easily the wheelchair user can carry out different tasks including propelling their wheelchair and transferring;

- when there is considerable high or low muscle tone, there can be difficulty and increased risk of aspiration with eating, drinking, swallowing and breathing. Aspiration is a life-threatening problem;

- increased risk of the development of fixed non-neutral postures;

- for some wheelchair users, high muscle tone can become greater with emotion, or when they are trying very hard to do something;

- high and low muscle tone can both be a risk factor for hip dislocations.

Considerations for Wheelchair Use with Altered Tone[edit | edit source]

When assisting a wheelchair user with altered muscle tone to move a wheelchair ensure you explain what you are going to do before you do it, move slowly and allow time for the wheelchair user to react, provide firm, comfortable support with your hands and arms so that the wheelchair user is well supported;

If high tone causes the whole body or whole limb extension, the tone can sometimes be relaxed by bending one joint e.g. if the whole leg goes into an extension pattern and the leg straightens, bending the knee or hip can reduce the tone. [6]

Often those with high tone will require additional postural support as high tone can cause points of high pressure between the user’s body and the wheelchair so can be at increased risk of pressure areas. Reduce the thigh-to-trunk angle to help reduce strong extension patterns common with high tone. Ensure the additional postural supports are strong enough to be effective with high muscle tone;. and reduce any risk of pressure areas from high force by distributing the force over a larger surface area. Check for signs of pressure frequently incorporating regular pressure relief through education of both the wheelchair user and their family member/caregiver. [1][6]

Fatigue[edit | edit source]

Some wheelchair users may regularly become tired during the day which may result from the additional effort and energy they use to sit upright and carry out activities, or the nature of their condition. Fatigue can be a common problem for some elderly people, and for some people with progressive conditions. [10][11]

Common Characteristics that may affect Wheelchair Provision with Fatigue[edit | edit source]

Poor upright posture can be a common characteristic in those individuals who have fatigue. While they are often able to sit upright, they often cannot maintain this upright posture for long secondary to fatigue, which puts them at an increased risk of developing postural problems or in many cases pressure areas.

Considerations for Wheelchair Use with Fatigue[edit | edit source]

Understanding what it is that makes the wheelchair user fatigued is vital to help find them the best solution for their wheelchair set up. When deciding how much postural support to provide, consider the effects of fatigue. Often this may mean incorporating elements of the assessment process when the individual is fatigued as often during the wheelchair assessment the wheelchair user may have more energy, and appear to need less support. Discuss carefully with the wheelchair user how much support they need when they are most tired. Consider incorporating alternative resting positions into their wheelchair set up to cater for fatigue i.e. a tray with a cushion can allow someone to lean forward on their arms; or tilt in space is another resting position. Encourage the wheelchair user to incorporate rest periods out of the wheelchair during the day where possible, which may make it possible for them to sit more comfortably for longer periods of time. [1]

Dislocated Hips[edit | edit source]

There is a higher prevalence of the hip dislocation in children who have never been able to walk independently [12][13][14], as the acetabulum on the pelvis is soft when children are born, and the round head of the femur shapes the socket when the leg is moving, or when weight is pushing through it when standing. If the hip joint does not form correctly, this can lead to dislocation. [1]

It is also very common with children who have tight muscles and high tone around the hip and pelvis and tend to always sit or lie with their legs to one side [13]. This can be a problem for people with cerebral palsy [13][15] or traumatic brain injury [15].

For children who haven’t walked and have a tendency to lie with both legs to one side (windswept): the hip, which is adducted and internally rotated is the one most likely to dislocate [16].

When children have low tone around the hip joint, they can also be at risk of hip dislocation. This is because the muscles and ligaments are not strong enough to hold the two parts of the hip joint together, the acetabulum and the head of the femur. A dislocated hip is not always painful [17][18][19].

Considerations for Wheelchair Use with Dislocated Hips[edit | edit source]

- Some indications that a person may have a dislocated/subluxed hip are:– one leg appears shorter than the other leg;

- their leg is always positioned closer to the mid line;

- there is pain when the hip is moved; [6]

- when carrying out a range of motion of the hip it may not be possible to take the thigh to the neutral position or to the outside of the body;

- it is not possible to fully straighten the hips.

- Research shows that the following can help to reduce the tendency for hip dislocation:

- When assessing a child or adult who has any of the signs of a possible dislocated hip, move the hips gently and avoid causing pain.

- If you are not sure if someone has dislocated hips refer them to a doctor or experienced physiotherapist for further advice.

- When providing a wheelchair and postural support for any person with a hip dislocation or suspected hip dislocation:

- avoid postures, which cause pain;

- support their pelvis and trunk in neutral or as close to neutral as possible; and then support the hips and thighs as close to neutral as possible. Avoid ‘overcorrecting’ the leg posture as this may cause the pelvis to move away from neutral and/or cause pain;

- check what position the person sleeps in. Advise on a sleeping position that avoids windsweeping of the legs, and the legs from being squeezed tightly against each other.

Epilepsy[edit | edit source]

Epilepsy is a disruption of the normal activity of the brain that results in seizures (67, 68, 69, 70). Under certain circumstances anyone can have a seizure (70). The term epilepsy is used only for recurrent, unprovoked seizures (69, 70). Some wheelchair users may have epilepsy.Seizures may be partial or generalized (70). During a partial seizure a person may or may not have impaired consciousness (70). If the consciousness is not impaired the seizure lasts less than a minute and a person is usually experiencing uncontrolled movements (72). If the consciousness becomes impaired, the seizure lasts one or two minutes and the person is slightly aware of what is going on but cannot respond or change his behaviour (70, 73). During a generalized seizure, a person has a complete loss of consciousness(70). A person experiencing a generalized seizure may suddenly fall unconsciousness and injure themselves (70). [1]

Common Characteristics that may affect Wheelchair Provision with Epilepsy[edit | edit source]

- What to do if a wheelchair user has a seizure during a wheelchair assessment: When providing a wheelchair for a person who has epilepsy remember: When a wheelchair user has a minor seizure, wait for it to be over and then continue with the assessment.

- If a wheelchair user has a major seizure the first priority is to protect them from injury (71). If the wheelchair user falls forward, try to ease the fall. If the wheelchair user is a child or a small adult, it may be possible to safely lift them onto the floor. If they are a large adult, it will be necessary for the wheelchair user to remain where they are (due to potential risk of injury to those assisting) and once the seizure stops, gradually lift them with the help of co-workers/family members or caregivers. [1]

During the seizure:

- do not try to remove the wheelchair user from the wheelchair, unless there is food, water or vomit in their mouth. In this case, remove the wheelchair user from their wheelchair and lie them on the side, so that saliva and mucus can run out of the mouth(70, 73);

- make space around the wheelchair user to protect him/her from injury or move them away from anything that can harm them (70);

- protect the wheelchair user’s head by placing soft padding underneath it (70, 73);

- loosen tight clothing, remove any objects that can harm them and make sure the wheelchair is secure (70, 73);

- time the duration of the seizure and give this information to the wheelchair user or his/her caregiver after the seizure (70).

- Wait calmly with the wheelchair user until the seizure is over. Seek medical attention if:

- the wheelchair user does not regain consciousness when the seizure has ended (69);

- the seizure lasts longer than five minutes (70).

Considerations for Wheelchair Use with Epilepsy[edit | edit source]

When providing a wheelchair for a person who has epilepsy remember:

- the wheelchair user will need straps that can be undone easily to help them out of the wheelchair;

- if a wheelchair user often has seizures, which cause them to fall forward suddenly, pad their tray (if used) so that they do not hurt their head;

- if a wheelchair user has epilepsy, which is not being treated, refer them to a doctor.

Lifestyle and Environment[edit | edit source]

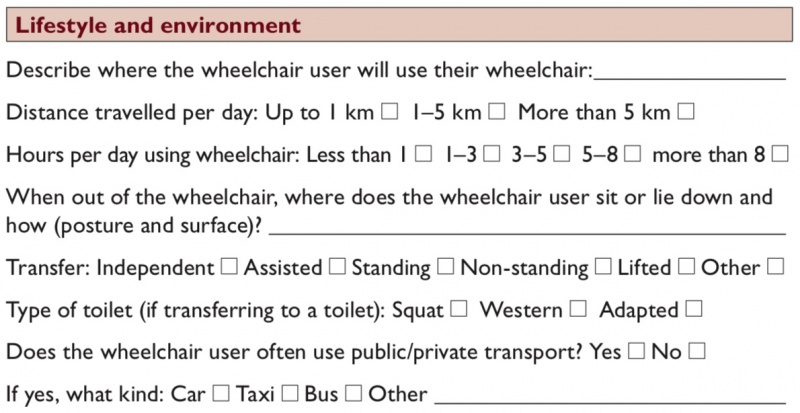

The ‘lifestyle and environment’ part of the wheelchair assessment form gathers information about where the wheelchair user lives and the things that they needs to be able to do in their wheelchair. It is important to consider how the wheelchair and any additional postural support provided will help the wheelchair user to manage to the best of their abilities considering their immediate environment and their lifestyle. [1]

Where will the Wheelchair User use their Wheelchair?[edit | edit source]

The wheelchair needs to be practical for the wheelchair user’s home, work or school e.g.

- if the wheelchair will be used at home, the wheelchair user needs to be able to move about the home easily to carry out important day-to-day activities;

- a wheelchair user who works in an office will need a wheelchair, which can fit easily into the office space;

- a wheelchair user who goes to school will need the wheelchair to fit comfortably in the classroom and under a desk, or will need a tray built on to the wheelchair;

- a wheelchair user who needs to travel to the market or to work on a rough track needs a wheelchair, which works well on rough terrain.

What Distance is Travelled per Day in the Wheelchair?[edit | edit source]

- Just as someone may walk if going a short distance, but use a bicycle for longer distances, a wheelchair user may use a wheelchair for shorter distances and a tricycle for longer distances.

- A tricycle takes less energy to cover the same distance and is faster.

How Many Hours per Day do they use the Wheelchair?[edit | edit source]

- The longer the wheelchair user sits in the wheelchair, the greater the risk of fatigue or a pressure sore. Think about how much support the wheelchair user needs and whether the cushion provides enough pressure relief and comfort.

- For any wheelchair user who is ‘active’ in their wheelchair during the day, the wheelchair should be set up to make pushing and other activities as efficient as possible. The position of the wheels is important. It is also important to check that the backrest supports the wheelchair user, but does not restrict freedom of movement of the shoulder blades.

Where and How does the Wheelchair User Sit or Lie When Out of their Wheelchair (Posture & Surface)?[edit | edit source]

- If a wheelchair user stays in the same position for long periods of time, he or she can become stiff and eventually stuck in that position. It may become impossible to sit comfortably in the wheelchair.

- It is very important to avoid this situation and provide the wheelchair user with various options of comfortable positions to sit or lie in when not in the wheelchair.

- Does the wheelchair user always sit or lie in the same position?

- if possible, ask him or her to demonstrate the position;

- it is important to know what the preferred position is so that a ‘counter’ (opposite) position can be suggested. It may not always be possible to go straight to the ‘counter’ position. If the wheelchair user has used their preferred posture for a long time, going for a completely opposite position straight away may be too uncomfortable, strange and potentially frightening;

- work out ways in which to support the trunk and limbs to position them in more neutral and comfortable positions.

- Is the wheelchair user able to change his or her position?

- if the wheelchair user is not able to change position, there is an increased risk of developing problems with posture or pressure sores.

How does the Wheelchair User Perform their Transfers ?[edit | edit source]

Armrests and footrests can affect how a wheelchair user gets in and out of the wheelchair:

- For standing transfers, it is helpful to have footrests, which move out of the way and armrests that the wheelchair user can use to push up;

- For non-standing transfers, removable armrests or armrests, which follow the profile of the wheels can make the transfer easier;

- When providing additional postural support, check that the wheelchair user can transfer easily. For example, by adding a seat or a cushion with a wedge, it may be more difficult for the wheelchair user to transfer. A change in technique may be needed, or a different PSD selected.

What Type of Toilet Do they Use?[edit | edit source]

- The type of toilet and physical access to the toilet will affect how easy it is for the wheelchair user to use it.

- It may not be possible to use the toilet because of the design. For example, most wheelchair users find it very difficult to use squat toilets.

- By asking about the toilet and where the toilet is, the wheelchair service personnel can offer advice on how to transfer to and from the toilet. Wheelchair service personnel may also offer advice on how to adapt the toilet.

Does the Wheelchair User often use Public/Private Transport?[edit | edit source]

- If a wheelchair user frequently uses transport, they will need to be able to transport the wheelchair easily. Different features of a wheelchair, which make transporting the wheelchair easier include the following:

- lighter wheelchairs are easier to lift in and out;

- removable wheels and folding frame and/or backrest make a wheelchair easier to transport.

- If using public transport, removable parts can be an advantage, as this makes the wheelchair easier to load. However, removable parts can also be a disadvantage, as parts may become separated and lost or stolen.

Existing Wheelchair[edit | edit source]

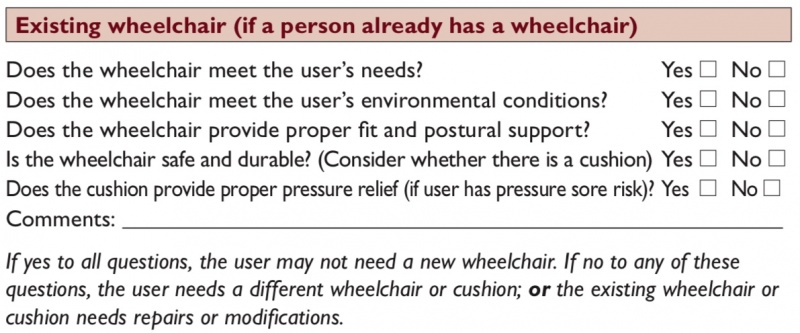

If a wheelchair user already has a wheelchair, it is important to find out if it is meeting his or her needs. The ‘existing wheelchair’ part of the wheelchair assessment form helps to guide the wheelchair service personnel and wheelchair user in assessing whether the existing wheelchair is appropriate for the wheelchair user. [1]

When looking at the condition of the wheelchair, look at the surfaces as these can give clues to how a wheelchair user is sitting. For example, a dented cushion on one side can mean there is more pressure going through one seat bone; damaged armrest on one side might mean a wheelchair user is leaning heavily on that side. If you notice anything unusual, ask the wheelchair user about it. If the wheelchair is not meeting the wheelchair user’s needs, the wheelchair service personnel should find out why. Sometimes the wheelchair is appropriate, but it may not have been correctly adjusted for the wheelchair user. Modifications, additional postural supports or repairs may help. [1]

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Sarah Frost, Kylie Mines, Jamie Noon, Elsje Scheffler, and Rebecca Jackson Stoeckle. Wheelchair Service Training Package - Reference Manual for Participants - Intermediate Level. World Health Organization, Geneva. 2013

- ↑ Lance JW. Symposium synopsis. In: Feldman RG,fckLRYoung RR, Koella WP (eds). Spasticity: Disordered Motor Control. Chicago, IL: Year Book 1980:485–94.

- ↑ Pandyan AD, Gregoric M, Barnes MP et al. Spasticity: clinical perceptions, neurological realities and meaningful measurement. Disabil Rehabil 2005;27:2–6.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Martin,K.,Kaltenmark,T.,Lewallen,A.,Smith,C.,&Yoshida,A.(2007).Clinical characteristics of hypotonia:A survey of pediatric physical and occupational therapists. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 19, 217–226.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 World Health Organization. (1993). Promoting the development of young children with cerebral palsy. Retrieved from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1993/WHO_ RHB_93.1.pdf

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 World Health Organzation, United States Department of Defense, Drucker Brain Injury Center MossRhab Hospital. (2004). Rehabilitation for persons with traumatic brain injury. Retrieved from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2004/WHO_DAR_01.9_eng.pdf

- ↑ Frederick M Maynard et al., International Standards for Neurological and Functional Classification of Spinal Cord Injury, American Spinal Injury Association, 1996

- ↑ World Health Organization. (2012). Stroke, Cerebrovascular Accident. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/topics/cerebrovascular_accident/en

- ↑ World Health Organization. (1996). Promoting independence following a spinal cord injury:A manual for midlevel rehabilitation workers. Retrieved from http://whqlibdoc. who.int/hq/1996/WHO_RHB_96.4.pdf

- ↑ World Health Organization. (2005).World diabetes day:Too many people are losing lower limbs unnecessary to diabetes. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2005/pr61/en

- ↑ Pecorro, R., Reiber, G., & Burgerss, E. (1990). Pathways to diabetic limb amputation: Basis for prevention. Diabetes Care, 13(5), 513–521

- ↑ Soo, B., et al. (2006). Hip displacement in cerebral palsy.The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 88, 121–129

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Scrutton, D., Baird, G., & Smeeton, N. (2001). Hip dysplasia in bilateral cerebral palsy: incidence and natural history in children aged 18 months to 5 years. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 43, 486–600

- ↑ Lonstein, J., & Beck, K. (1986). Hip dislocation and subluxation in cerebral palsy. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics, 6, 521–526

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 World Health Organzation, United States Department of Defense, Drucker Brain Injury Center MossRhab Hospital. (2004). Rehabilitation for persons with traumatic brain injury. Retrieved from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2004/WHO_DAR_01.9_eng.pdf

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Pope, P. (2007). Severe and complex neurological disability: Management of the physical condition. Philadelphia: Elsevier Limited.

- ↑ Sherk, H., Pasquariello, P., & Doherty, J. (2008). Hip dislocation in cerebral palsy: Selection for treatment. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 25(6), 738–746. 65

- ↑ Moreau, M. et al. (1979). Natural history of the dislocated hip in spastic cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 21(6), 749–753.

- ↑ Knapp, R., & Cortes, H. (2002). Untreated hip dislocation in cerebral palsy. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics, 22, 668–671.

- ↑ Pountney,T., Mandy,A., Green, E., & Gard, P. (2009). Hip subluxation and dislocation in cerebral palsy – a prospective study on the effectiveness of postural management programmes. Physiotherapy Research International, 14(2), 116–127.

- ↑ Health Centre for Children. (2011). Evidence for practice: Surveillance and management of hip displacement and dislocation in children with neuromotor disorders including cerebral palsy.Vancouver, BC:Tanja Mayson.