Ventricular Extrasystole

Original Editor - Elyssa Abou Jamra

Top Contributors - Elyssa Abou Jamra, Kim Jackson and Lucinda hampton

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) are early depolarizations of the myocardium originating in the ventricule. It is the expression of an impulse that arises prematurely in an ectopic ventricular focus and is, in some way, related to the preceding sinus beat. [1]

Extrasystoles are everyday findings on clinical examinations or electrocardiographic records of outpatients referred from primary care facilities and may be either asymptomatic or symptomatic. While they may be benign in nature, evaluation of their clinical implications and potential association with other clinical variables is necessary.[2]

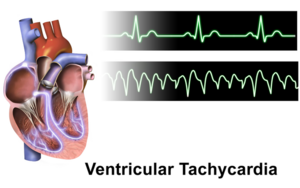

The most common forms of premature ectopic ventricular impulse formation are ventricular extrasystoles and ventricular tachycardia. [3]The manifestation of the ectopic rhythm may be an expression of underlying disease. [4]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The prevalence of PVCs is directly related to the study population, the detection method, and the duration of observation. PVCs are more likely to be detected in older patients, patients with more comorbidities, and patients who are monitored for longer durations of time [5]

In patients with no known heart disease, PVCs have been seen in approximately 1 percent of routine 12-lead electrocardiograms (ECG) of 30 to 60 seconds duration and up to 6 percent of ECGs of two minutes duration [6][7]. By comparison, when 24-hour ambulatory monitoring is used, up to 80 percent of apparently healthy people have occasional PVCs .[8] [9],The occurrence of frequent PVCs accounting for more than 20 percent of overall heart beats is rare, seen in less than 2 percent of patients[10].

There is an age-related increase in the prevalence of PVCs in normal individuals and those with underlying heart disease[6] [7][9][11]. The prevalence of PVCs increase with age and in the presence of other factors, such as faster sinus rate, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, and hypertension .[7]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Common known etiologies include:

- Excess caffeine consumption, excess catecholamines,[12] high levels of anxiety, and electrolyte abnormalities.

- Specific electrolyte:

- low blood potassium

- low blood magnesium

- high blood calcium.

- Alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs

- Patients suffering from sleep deprivation

- There are numerous cardiac and non-cardiac pathologies that are causative,examples:

- Cardiomyopathy

- Mitral valve prolapse

- Myocardial infarction.

- Any structural heart disease that alters conduction pathways due to tissue alterations

- Non-cardiac examples :

Patient populations with higher risks of cardiovascular disease and clinically poor cardiovascular markers have a higher occurrence of PVCs.[13]

Triggering Factors[edit | edit source]

- Stress

- dehydration,

- poor sleep,

- alcohol,

- medication

- health changes,

- stimulant or recreational drug use,

- temporal relationship between phases of hormonal cycles [14]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

- One pathophysiological reason for the occurrence of PVCs is ectopic nodal automaticity. This suggests that ectopic pacemaker cells carry a subthreshold potential for firing. If the threshold is reached via the heart's electrical activity, an ectopic beat occurs.

- A second pathophysiologic explanation is re-entrant signaling. If one pathway of the Purkinje fibers is blocked and another path is experiencing slower conduction, this can trigger an ectopic beat on the post-block pathway.

- The final explanation for PVCs is that triggered beats occur due to after-depolarizations.[15]

On the molecular level, there are a few changes that create an environment for spontaneous depolarization of the ventricular myocytes. These include hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, excess calcium, and excess catecholamines.[16]

In some cases, the triggered beat may occur in patients with digoxin toxicity and following reperfusion after an MI.

Assessment[edit | edit source]

History:

- Detailed history of the presenting symptom - including onset, duration, associated symptoms and recovery.

- Check for other cardiac symptoms including chest pain, breathlessness, syncope or near syncope (eg, dizziness), and arrhythmia symptoms (eg, sustained fast palpitations).

- If there is history of syncope, note that:

- Exertional syncope should always raise alarm of a sinister cause.

- Rapid recovery after the syncopal event, without confusion or drowsiness, is characteristic of cardiac syncope.

- Family history - for early cardiac disease or sudden death.

- Previous cardiac disease or coronary heart disease (CHD) risk factors.

Symptoms[edit | edit source]

Many patients are entirely asymptomatic, whereas other describe symptoms of:

- palpitations (heart pounding, irregular, skipped, or paused heartbeat)

or they may convey more generalized symptoms such as

- dizziness

- near-syncope

- dyspnea

- chest pain

- fatigue.

Symptoms can be due to the ventricular extrasystole itself, to the compensatory pause followed by a hypercontractile beat (Starling effect), or to a reduction in effective cardiac output .[14]

Examination

- Blood pressure

- Pulse

- Pulse oximetry

- Cardiac findings

- Cardiopulmonary findings

- Neurologic findings

Investigations

- Resting 12-lead ECG.

- FBC and TFTs.

- Electrolytes.

Other investigations:

- Serum calcium and magnesium.

- If symptoms have a long duration (many hours), advise the patient to attend their GP surgery or A&E for a 12-lead ECG during the next episode.

- Ambulatory ECG monitoring:

- If symptoms are short-lived but frequent (>2-3 times per week), use a 24-hour Holter monitor.

- If symptoms are short-lived and infrequent (<1 per week), use an event monitor or transtelephonic recorder.

- Echocardiography - to assess LV function and heart structure.

- Exercise stress testing - the relation of extrasystoles to exercise may have prognostic importance.

- Further non-invasive cardiac imaging may be required.[17]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Patients with no symptoms/minor symptoms only - no heart disease, ventricular extrasystoles which reduce in frequency on exercise testing, and no documented ventricular tachycardia:

- These patients can be reassured.

- Reducing caffeine intake (if high) can be tried to see if this reduces symptoms.

- If treatment is desired, consider beta-blockers.

Patients with no heart disease, but with frequent ventricular extrasystoles (>1,000 per 24 hours):

- No treatment is required, but these patients may merit long-term follow-up, with periodic reassessment of LV function, particularly for those with very high-frequency extrasystoles.

Patients with no heart disease, with frequent unifocal ventricular extrasystoles and particularly if ventricular tachycardia or salvos are induced on exercise:

- Consider catheter ablation - this may be curative and results are often good.

Patients with cardiac disease:

- Ventricular extrasystoles may indicate either an arrhythmia risk or the severity of the underlying disease; therefore, consider the level of risk for sudden cardiac death.

- Beta-blockers may be indicated either for the underlying cardiac disease, or because they may reduce the frequency or symptoms of ventricular extrasystoles.

- Consider implantable cardiac defibrillators if at high risk of serious ventricular arrhythmia.

- Consider catheter ablation as adjunctive treatment.

Also treat any underlying cardiac disease and contributing factors - eg, hypertension, electrolyte abnormalities, ischaemia or cardiac failure.[18]

Summary[edit | edit source]

- Ventricular ectopic beats (PVCs) are frequently seen in daily clinical practice and are usually benign.

- Presence of heart disease should be sought and, if absent, indicates good prognosis in patients with PVCs.

- Unifocal PVCs arising from the right ventricular outflow tract are common and may increase with exercise and cause non-sustained or sustained ventricular tachycardia. Catheter ablation is effective and safe treatment for these patients.

- B-blockers may be used for symptom control in patients where PVCs arise from multiple sites. It should also be considered in patients with impaired ventricular systolic function and/or heart failure.

- Risk of sudden cardiac death from malignant ventricular arrhythmia should be considered in patients with heart disease who have frequent PVCs. An implantable cardioverter defibrillator may be indicated if risk stratification criteria are met.

- PVCs have also been shown to trigger malignant ventricular arrhythmias in certain patients with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation and other syndromes. Catheter ablation may be considered in some patients as adjunctive treatment.[20]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Ahn MS. Current Concepts of Premature Ventricular Contractions. J Lifestyle Med. 2013;3(1):26-33.

- ↑ Ribeiro, Wilma Noia; Yamada, Alice Tatsuko; Grupi, Cesar José; Silva, Gisela Tunes da; Mansur, Alfredo Jose; Aalto-Setala, Katriina (2018). Premature atrial and ventricular complexes in outpatients referred from a primary care facility. PLOS ONE, 13(9), e0204246–. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0204246

- ↑ Leo Schamroth (1980). Ventricular extrasystoles, ventricular tachycardia, and ventricular fibrillation: Clinical-electrocardiographic considerations. , 23(1), 13–32. doi:10.1016/0033-0620(80)90003-1

- ↑ Scherf D, Schott A: Extrasystoles and Allied Arrhythmias. London, William Heinemann, 1953

- ↑ Marcus GM. Evaluation and Management of Premature Ventricular Complexes. Circulation 2020; 141:1404.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 HISS RG, LAMB LE. Electrocardiographic findings in 122,043 individuals. Circulation 1962; 25:947.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Simpson RJ Jr, Cascio WE, Schreiner PJ, et al. Prevalence of premature ventricular contractions in a population of African American and white men and women: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am Heart J 2002; 143:535.

- ↑ Sobotka PA, Mayer JH, Bauernfeind RA, et al. Arrhythmias documented by 24-hour continuous ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring in young women without apparent heart disease. Am Heart J 1981; 101:753.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Brodsky M, Wu D, Denes P, et al. Arrhythmias documented by 24 hour continuous electrocardiographic monitoring in 50 male medical students without apparent heart disease. Am J Cardiol 1977; 39:390.

- ↑ Yang J, Dudum R, Mandyam MC, Marcus GM. Characteristics of unselected high-burden premature ventricular contraction patients. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2014; 37:1671.

- ↑ Glasser SP, Clark PI, Applebaum HJ. Occurrence of frequent complex arrhythmias detected by ambulatory monitoring: findings in an apparently healthy asymptomatic elderly population. Chest 1979; 75:565.

- ↑ Frigy, Attila; Csiki, Endre; Caraşca, Cosmin; Szabó, István Adorján; Moga, Victor-Dan (2018). Autonomic influences related to frequent ventricular premature beats in patients without structural heart disease. Medicine, 97(28), e11489–. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000011489

- ↑ Ribeiro WN, Yamada AT, Grupi CJ, da Silva GT, Mansur AJ. Premature atrial and ventricular complexes in outpatients referred from a primary care facility. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0204246.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Gorenek, Bulent; Fisher, John D.; Kudaiberdieva, Gulmira; Baranchuk, Adrian; Burri, Haran; Campbell, Kristen Bova; Chung, Mina K.; Enriquez, Andrés; Heidbuchel, Hein; Kutyifa, Valentina; Krishnan, Kousik; Leclercq, Christophe; Ozcan, Emin Evren; Patton, Kristen K.; Shen, Win; Tisdale, James E.; Turagam, Mohit K.; Lakkireddy, Dhanunjaya (2019). Premature ventricular complexes: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations in clinical practice. Journal of Interventional Cardiac Electrophysiology, (), –. doi:10.1007/s10840-019-00655-3

- ↑ Karaman K, Karayakali M, Arisoy A, Akar I, Ozturk M, Yanik A, Yilmaz S, Celik A. Is There any Relationship Between Myocardial Repolarization Parameters and the Frequency of Ventricular Premature Contractions? Arq Bras Cardiol. 2018 Jun;110(6):534-541.

- ↑ Wang Y, Eltit JM, Kaszala K, Tan A, Jiang M, Zhang M, Tseng GN, Huizar JF. Cellular mechanism of premature ventricular contraction-induced cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2014 Nov;11(11):2064-72

- ↑ Robinson KJ, Sanchack KE; Palpitations. StatPearls Publishing 2019.

- ↑ (2015). 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. European Heart Journal, (), ehv316–. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv316

- ↑ Alila Medical Media. Premature Ventricular Contractions (PVCs), Animation . Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wBs4fowZmzs [last accessed 22/11/2021]

- ↑ Ng, G A. (2006). Treating patients with ventricular ectopic beats. Heart, 92(11), 1707–1712. doi:10.1136/hrt.2005.067843