Vaginal Cancer

Original Editor - Khloud Shreif

Top Contributors - Khloud Shreif and Sehriban Ozmen

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Vaginal cancer can be secondary as the cancer has spread from other sites such as cervix, uterus, bladder, or other nearby organs to the vagina or be primary in origin and it is rare to happen. Primary vaginal cancer does not include those with a history of vulvar or cervix cancer in the last 5 years. There are two types of vaginal cancer, squamous cell carcinoma that forms in the flat cells lining the vagina it is the most common type pf vaginal cancer it is usually stay in its site and when it spread it spread slowly to lung, bone, or liver and the second type is adenocarcinoma. It is more common in postmenopausal and elderly women than women under 40 years. It grows very slowly and the prognosis depends on the size, spread, and the patient's general health. Primary vaginal cancer represents about 1-2% of all female genital tract malignancies[1]and 10% of all vaginal malignant neoplasms[2]. Cervical screening helps to identify the abnormality and find the treatment early.

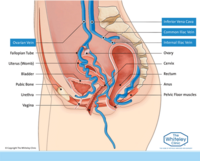

Anatomy Background[edit | edit source]

The internal female reproductive system consists of ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, and vagina.

The vagina is an elastic fibromuscular canal connecting the cervix with the vulva. It acts as a birth canal, an outlet for the menstrual blood flow, and a cavity for sexual intercourse.

Epidimology[edit | edit source]

Primary vaginal cancer is more common in postmenopausal and elderly women about 50% of patients diagnosed with vaginal cancer are above seventy, and about 20% are above eighty. In USA about 2890 are diagnosed with primary vaginal carcinoma every year[3].

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Vaginal cancer like cervical cancer is strongly associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, it may be caused by any skin-to-skin contact of the genital area, and vaginal, anal, or oral sex. In countries with a high prevalence of HPV, there is a high risk for HIV infection and there are reported cases of primary vaginal cancer in young women[1].

Co-factors such as smoking, immunosuppression, multiple sexual partners, history of previous cervical cancer or intraepithelial neoplasia[4], and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion HSIL are considered risk factors for vaginal cancer.

Symptoms[edit | edit source]

A woman with vaginal cancer may complain of the following symptoms but it does not necessarily mean it is vaginal cancer, it can also be caused by many different conditions/ impairments.

- Lump in the vagina and can be felt.

- Pain during sex or abnormal vaginal bleeding after sex.

- Abnormal vaginal discharge.

- Bleeding between periods.

- Itching sensation in the vagina that does not go away.

- Ulcer and skin changes.

- Constipation.

Pattern of Spread[edit | edit source]

- Vagianl cancer can spread to the surrounding soft tissue structures of the pelvis (parametria, urethra, bladder, and rectum).

- Spread to the lymph nodes, it may spread to the obturator, internal iliac (hypogastric), and external iliac nodes if it is in the upper vagina, and to groin nodes if it is in the lower vagina.

- Spread to remote places (lung, liver, or bone) and this is considered the late manifestation.

FIGO Staging of Primary Vaginal Cancer[edit | edit source]

Internaltional federation of gynacelogy and obstertrics FIGO classified the vaginal cancer according to the size of the tumor if it is in situ or reached any nearby sites in the pelvis T, the spread of the tumor to nearby lymph nodes N, and spread to distant sites M (organs or lymph nodes)[1].

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Stage 0 | Carcinoma in situ, intraepithelial carcinomaa |

| Stage I | Confined to the vagina |

| Stage II | Involvement of paravaginal tissue but not pelvic sidewall |

| Stage III | Extension to pelvic sidewall |

| Stage IV | Extension beyond true pelvis or bladder and/or rectal involvement |

| IVa | Extension beyond pelvis, bladder or rectal invasion |

| IVb | Distant organ metastases |

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

The treatment of vagianal cancer is often individualized, complex, and needs to understand the extent of the disease, because of its similar etiology to cervical cancer the primary vaginal cancer treatment was inspired by cervical cancer. MRI is considered an important procedure to detect the tumor size and initial staging for follow-up and better treatment planning[6]. Primary vaginal cancer is confirmed by directed biopsy to ensure there is no evidence of a tumor on the cervix or the vulva.

- Radiation and chemotherapy

- Surgical treatment is used in the early stages or with those in situ[7].

- Brachytherapy (BT).

According to FIGO classification for stage I of vaginal cancer, BT and external beam radiation therapy EBRT are recommended or surgical excision for small size <2 cm. Chemotherapy with EBRT is recommended to be used with stage IVB.

HPV vaccination for primary prevention from vaginal cancer is important.

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

The physical therapy role with patients with cancer pre or post-treatment concentrates on improving their quality of life QoL, and helping them to continue their activity of daily livings without fatigue or exhaustion. It will concentrate on exercise therapy and pain management when it is needed.

One of the side effects after treatment of gynecological cancer (cervical, anorectal, or vaginal) treated with chemotherapy or radiotherapy is radiation-induced vaginal stenosis. It causes impairment in sexual Qol[8]. Pelvic floor physiotherapy intervention will help to improve sexual function and health-related quality, especially in a female cancer patient with genitourinary syndrome. Our physiotherapy role will iclude; patient education, manual physical therapy techniques, biofeedback, pelvic floor muscle training, general exercise programme, and home training programme[9][10].

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Adams TS, Rogers LJ, Cuello MA. Cancer of the vagina: 2021 update. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2021 Oct;155:19-27.

- ↑ Adhikari P, Vietje P, Mount S. Premalignant and malignant lesions of the vagina. Diagnostic Histopathology. 2017 Jan 1;23(1):28-34.

- ↑ Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2016 Jan;66(1):7-30.

- ↑ Strander B, Hällgren J, Sparén P. Effect of ageing on cervical or vaginal cancer in Swedish women previously treated for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3: population based cohort study of long term incidence and mortality. Bmj. 2014 Jan 14;348.

- ↑ Medical Centric. Vaginal cancer, Causes, Signs and Symptoms, DIagnosis and Treatment. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2AzJeREYqeE[last accessed 15/6/2022]

- ↑ Gardner CS, Sunil J, Klopp AH, Devine CE, Sagebiel T, Viswanathan C, Bhosale PR. Primary vaginal cancer: role of MRI in diagnosis, staging and treatment. The British journal of radiology. 2015 Aug;88(1052):20150033.

- ↑ Frank SJ, Jhingran A, Levenback C, Eifel PJ. Definitive radiation therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina. International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics. 2005 May 1;62(1):138-47.

- ↑ Morris L, Do V, Chard J, Brand AH. Radiation-induced vaginal stenosis: current perspectives. International journal of women's health. 2017;9:273.

- ↑ Li J, Huang J, Zhang J, Li Y. A home-based, nurse-led health program for postoperative patients with early-stage cervical cancer: A randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Oncology Nursing.2016;21:174-180.

- ↑ Brennen R, Lin KY, Denehy L, Frawley HC. The effect of pelvic floor muscle interventions on pelvic floor dysfunction after gynecological cancer treatment: A systematic review. Physical therapy. 2020 Aug 12;100(8):1357-71.