Upper Respiratory Airways

Original Editor - Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka

Top Contributors - Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Adam Vallely Farrell and Kardelen Aktas

Introduction[edit | edit source]

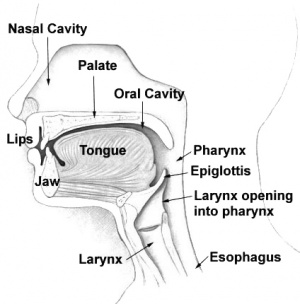

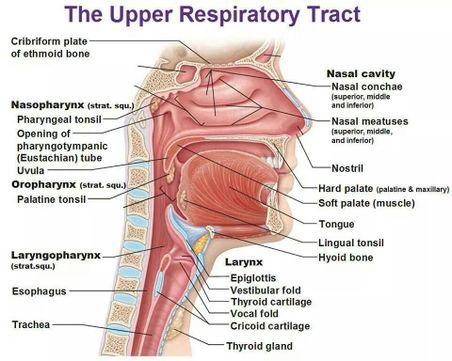

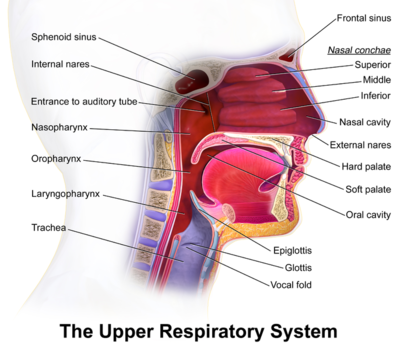

The respiratory system is structurally divided into the upper and lower respiratory airways. The upper airways are made of the nose, nasal cavity, and pharynx while the lower airways are the larynx; trachea, bronchial tree and the lungs.

The Nose[edit | edit source]

The nose has an external portion and an internal portion inside the skull. It is formed by an upper framework of bone (made up of the nasal bones, the nasal part of the frontal bones and the frontal processes of the maxillae), a series of cartilages in the lower part, and a small zone of fibro-fatty tissue that forms the lateral margin of the nostril (the ala).It is divided into two by the nasal septum.

The nasal septum is usually straight at birth and it remains straight through out early childhood, but as a person ages, the septum bends toward one side. This may cause obstruction of the nasal cavity making breathing difficult[1]. The interior part superior and posterior to the nose consist of the nasal cavity.

The nasal cavity[edit | edit source]

The nasal cavity starts from the nostrils to the choanae, The choanae are the oval-shaped openings between the nasal cavities and the nasopharynx[2] . The anterior part of the nasal cavity inside each nostrils, contains the vestibule which is a dilated chamber and it is lined with coarse hairs or vibrissae with stratified squamous epithelium(which is continuous with the stratified squamous epithelium of the skin). The nasal septum that is composed of bone and cartilage divides the nasal cavity into right and left chambers called nasal fossae.

The lateral wall of the fossa gives rise to three folds of tissues: the superior, middle, and inferior nasal conchae.

The conchae subdivide each side of the nasal cavity into series of groove-like passages (superior, middle and inferior nasal meatus). The conchae consist of mucous membranes supported by thin scroll-like turbinate bones. The conchae greatly increase the surface area of the mucus membrane over which air travel[3]. The mucus membrane contains mucus secreting goblet cells and an extensive network of blood vessels that deliver heat and moisture[4]. The hard palate forms the floor of the nasal cavity and separates it from the oral cavity.

Blood supply and Venous drainage[5][2][edit | edit source]

The upper part of the nasal cavity receives its arterial supply from the anterior and posterior ethmoidal branches of the ophthalmic artery; a branch of the internal carotid artery.

The sphenopalatine branch of the maxillary artery is distributed to the lower part of the cavity and links up with the septal branch of the superior labial branch of the facial artery on the antero-inferior part of the septum. It is from this part, just within the vestibule of the nose, that epistaxis occurs in some 90% of cases.

A sub mucous venous plexus drains into the sphenopalatine, facial and ophthalmic veins.

Nerve supply[6][2][edit | edit source]

The olfactory nerve supplies the specialized olfactory zone of the nose, which occupies an area in the uppermost parts of the septum and lateral walls of the nasal cavity.

The septum is supplied majorly by the nasopalatine nerve, derived from the maxillary nerve via the pterygopalatine ganglion.

The lateral wall is innervated in the region of the superior and middle conchae, by the lateral posterior superior nasal nerve. The inferior concha receives branches from the anterior superior alveolar nerve (arising from the maxillary nerve in the infra-orbital canal) and from the anterior (greater) palatine nerve (derived from the pterygopalatine ganglion). The anterior part of the lateral wall, in front of the conchae, is supplied by the anterior ethmoidal branch of the nasociliary nerve.

The anterior ethmoidal nerve innervates the cartilaginous tip of the nose on both its inner and outer aspects.

The floor is supplied in its anterior part by the antero-superior alveolar nerve and posteriorly by the anterior (greater) palatine nerve.

The vestibule receives terminal fibres of the infra-orbital branch of the maxillary nerve, which also supplies the skin immediately lateral to, and beneath, the nose.

Pharynx[edit | edit source]

The pharynx is a half tube(concave) shaped musculofascial passage connecting the oral and nasal cavities in the head to the larynx and esophagus in the neck. The pharyngeal cavity is a common pathway for air and food. The pharynx is attached above to the base of the skull and is continuous below with the top of the esophagus approximately at the level of vertebra CVI[4]. The walls of the pharynx are attached anteriorly to the margins of the nasal cavities, oral cavity, and larynx.Thus, the pharynx is divided into the nasopharynx, the oropharynx and the laryngopharynx.

The nasopharynx extends from the choanae down to the lower margin of the soft palate. The soft palate bears the uvula centrally and it blends on either side with the pharyngeal wall. The anterior aspect faces the mouth cavity while the posterior aspect forms part of the nasopharynx. It is lined with mucous membrane containing pseudo stratified ciliated columnar epithelium with goblet cells. Paralysis of the muscles of the soft palate results in a typical nasal speech and in regurgitation of food through the nose[4].

The mucosa of the posterior nasopharyngeal wall contains a collection of lymphoid tissue termed the single pharyngeal or adenoid tonsil. This structure can hypertrophy and produce nasal obstruction, which can contribute to obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in children[7] . The muscular structures in the wall of the nasopharynx and soft palate play a major role in speech, swallowing[8], and breathing. These muscles act to partition airflow between the oral and nasal routes, particularly under conditions of increased ventilatory drive. The palatal muscles are also important in the maintenance of airway patency.

The oropharynx extends from the soft palate to the epiglottis. Laterally, it is bordered by the anterior (palatoglossal) and posterior (palatopharyngeal) tonsillar pillars, which merge superiorly into the soft palate and between which lie the fossae of the palatine tonsils. Posteriorly, the pharyngeal wall is largely composed of the pharyngeal constrictor muscles. The oropharynx serves as the main channel for both solids and liquids from the mouth to the oesophagus and for the flow of air through to the larynx[3]. The uvula prevents swallowed materials from entering the nasopharynx and the nasal cavity[5].

The laryngopharynx extends from the tip of the epiglottis to the oesophagus and passes posteriorly to the larynx. The laryngopharynx is lined with stratified squamous epithelium. However, the pharynx is a collapsible muscular tube compared to the nasal and laryngeal segments of the upper airway which are supported by bony and cartilaginous structures[9].

Muscles of the pharynx[2][9][edit | edit source]

The muscles of the pharynx are the superior, middle, and inferior constrictors by the name stylopharyngeus, salpingopharyngeus and palatopharyngeus respectively. The constrictor muscles have an extensive origin from the skull, mandible, hyoid and larynx on either side.

They sweep round the pharynx to become inserted into the median raphe, which runs the length of the posterior aspect of the pharynx, being attached above to the pharyngeal tubercle on the basilar part of the occipital bone and blending below with the oesophageal wall.

Vascular, lymphatic and nerve supply[9][5][3][edit | edit source]

The blood supply of the palatine tonsil is the tonsillar branch of the facial artery and runs with it's two venae comitantes, to pierce the superior constrictor muscle and enter the inferior pole of the tonsil. In addition, branches from the lingual, ascending palatine, ascending pharyngeal and maxillary arteries all add their contributions.

Venous return are via the venae comitantes and a paratonsillar vein to join the pharyngeal venous plexus. It is this vein which is the cause of occasional unpleasant venous bleeding after tonsillectomy.

Lymphs drains into the upper deep cervical nodes; the jugulo-digastric node or tonsillar node. The palatine and pharyngeal tonsils, as well as the lymph collections on the posterior part of the tongue form a continuous ring of lymphoid tissue around the pharyngeal entrance, which is termed Waldeyer’s ring.

Sensory supply to the pharynx is via:

· the glossopharyngeal nerve via the pharyngeal plexus;

· the posterior palatine branch of the maxillary nerve;

· twigs from the lingual branch of the mandibular nerve

The constrictor muscles are supplied by the pharyngeal nerve plexus, which transmits the fibres of the accessory nerve in the pharyngeal branch of the vagus. In addition, the inferior constrictor supplied vie a branch of the external superior laryngeal and the recurrent laryngeal branch of the vagus.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Shier D, Butler J, Lewis R. Hole’s Essentials of human anatomy and physiology. 7th eds. McGraw Hill, 2010

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Drake, RL, Vogl, W, Mitchell, AW, Gray, H. Gray's anatomy for Students 2nd ed. Philadelphia : Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier, 2010

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Drake, RL, Vogl, W, Mitchell, AW, Gray, H. Gray's anatomy for Students 2nd ed. Philadelphia : Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier, 2010

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Patwa A, Shah A. Anatomy and physiology of respiratory system relevant to anaesthesia. Indian journal of Anaesthesia, 2015; 59(9): 533–541. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.165849

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Moore, KL, Dalley, AF, Agur, AM. Clinically oriented anatomy. 7th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2014

- ↑ Hamid, Q., Shannon, J. and Martin, J. 2005. Physiologic basis of respiratory disease. BC Decker Inc.

- ↑ Hamid Q, Shannon J, Martin J. Physiologic basis of respiratory disease. BC Decker Inc.2005

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780323049719000111

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Ellis H, Feldman S, Harrop-Griffiths W. Anatomy for Anaesthetists . 8th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2004