Turf toe

Original Editors - Charlotte Sirago

Top Contributors - Charlotte Sirago, Kim Jackson, Admin, Shaimaa Eldib, Fasuba Ayobami, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Wanda van Niekerk, Jess Bell, Khloud Shreif, 127.0.0.1, Rachael Lowe, Evan Thomas, Oyemi Sillo, Naomi O'Reilly, WikiSysop and Claire Knott

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

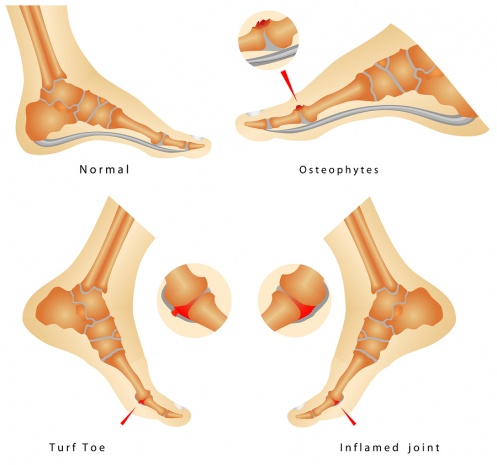

Turf toe is an injury of the first metatarsophalangeal(MTP) articulation, due to hyperextension of the big toe, which leads to damage of the plantar capsuloligamentous complex. It may cause tearing or complete disruption of these structures.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

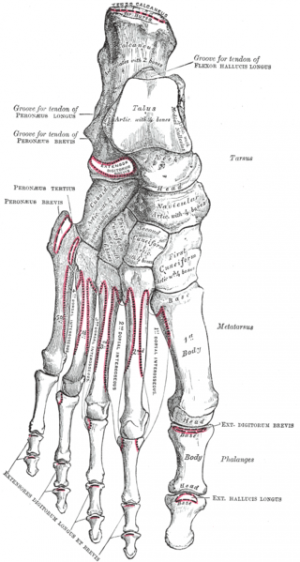

The slightly concave shape of the proximal phalanx with which the first metatarsal articulates creates little joint stability. The plantar capsule is thicker on the proximal phalanx and finishes in a thinner part on the metatarsal head. It supports the under surface of the metatarsal head and resists hyperextension of the metatarsophalangeal joint.[1] Additionally to the plantar capsule and the collateral ligaments, the MTP joint is dynamically stabilized by the flexor hallucis brevis (FHB)(the hallucal sesamoids embedded in the FHB tendons), the adductor hallucis and the abductor hallucis tendons.[2]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

In 1976 turf toe was for the first time described by Bowers and Martin, they studied the soccer players at the University of West Virginia and ascertained that during one season there where an average of 5,4 turf toe injuries.[2][3]

Further studies showed that the injury was much more frequently by soccer played on artificial turf surfaces.

It is caused by an overload on the hallux MTP joint in hyper-dorsiflexion position as happens when one player falls on another players’ heel.

Too strong adhesion at the surface so that the shoe sticks, while the bodyweight moves forwards when the player tries to stop quickly may cause an acute turf toe. A chronical condition is mostly caused by frequent running and jumping with extremely flexible shoes.[2][4][5] [6]

The injury results very often not due only to hyperextension but also to a degree of valgus stress.

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

It is characterized by pain as a first symptom, localized swelling, ecchymosis and stiffness of the joint.

With an appropriate evaluation we can divide the disease in three grades, each with his proper symptoms and treatments.

- Grade I injury symptoms are: local swelling, plantar structures attenuation or stretching, minimal ecchymosis.

- Grade II injury symptoms are: moderate swelling, partial tear of plantar structures and restricted motion as result of pain.

- Grade III injury symptoms are: indicative swelling and ecchymosis, total disruption of the plantar structures, weakness of the hallux flexion, and high instability of the MTP joint.[2][3]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Reverse turf toe or soccer toe, Hallux rigidus, Hallux limitus, Hallux valgus

Examination[edit | edit source]

The physical examination starts with observation and palpation of the sensitivity on the hallux MTP joint, evaluating the stability and the flexion strength. The palpation focuses especially the collateral ligaments, dorsal capsule and the plantar sesamoid complex.[2]

If pain is localized on the proximal sesamoids it indicates a strain of the flexor hallucis brevis musculotendinous junction, while turf toe injury is located distal to the sesamoids.

Various range of motion manoeuvres of the joint indicate different injuries.

Varus and valgus stress do test the collateral ligaments; the dorsoplantar drawer test (Thompson and Hamilton)[7][8] tells about the competence of the plantar plate; active flexion and extension at the MTP and interphalangeal joints give indications about the extensor and flexor tendons and the plantar plate. Comparing the active flexion strength with the contralateral side, may reveal a disruption of the FHB or plantar plate.[2]

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

Injection therapy may be considered a therapeutic adjunct.[9]

The indications for a surgical treatment are the following:[2]

- Large capsular avulsion with unstable MTP joint

- Diastasis of bipartite sesamoid

- Diastasis of sesamoid fracture

- Retraction of sesamoid

- Traumatic hallux valgus deformity

- Vertical instability (positive Lachman test result)

- Loose body in MTP joint

- Chondral injury in MTP joint

- Failed conservative treatment

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

The three grades of the injury got a different physical therapy but the initial approach for all three consists in the RICE (rest, ice, compression, elevation) application.

Grade I

Once the acute phase is over, taping in a lightly plantar flexion protects the toe from a too big range of motion and supplies compression. 3 to 5 days after the injury it’s possible to start early rehabilitation consisting in a gentle passive plantarflexion and gradual strengthening. Distraction and dorsal and proximal sliding of the proximal phalanx on the first metatarsal can help restoring a normal ROM and strength.[10] The patient may do athletic activity as bicycling, pool therapy and elliptical training.[2]

It’s advisable that the athlete wears stiff-soled shoes limiting the motion of the hallux.[2][3]

Grade II

A second grade turf toe needs at least 2 weeks to return to activity depending on the athletes’ sport. To increase the range of motion and reduce the pain, passive joint mobilizations are indicated. After the symptoms, as pain and swelling, have been reduced the athlete can start rehabilitation in a soft way with a toe protection, such as a turf toe plate or a Morton’s extension. To control inflammation and assist the healing of the soft tissues, pulsed ultrasound or ionophoresis can be applied. Active exercises can be done; toe extension and flexion exercises like toe crunches, curling up a towel with the toes, moving the toes in a bucket of sand and short foot exercises.[10]

When possible, the athlete can progress to higher impact activities (jogging, running, cutting and jumping).[2][4]

Grade III

The nonsurgical management of a third grade injury requires 8 weeks of recovery and immobilization in plantar flexion. Before restarting sport activity, the hallux MTP joint should return to a 50° to 60° painless passive dorsiflexion motion. Complete rehabilitation can take up to 6 months.[2]

The most important part of the treatment for turf toe is physical therapie rehabilitation and prevention by using of protections, but in certain cases a surgical intervention may be necessary.[2]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Yao L, Do HM, Cracchiolo A, Farahani K.- Plantar plate of the foot: findings on conventional arthrography and MR imaging, AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994 Sep;163(3):641-4.fckLRBooks

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 Jeremy J., McCormick, MD, Robert B. Anderson, MD -Turf Toe: Anatomy, Diagnosis, and Treatment, Clin Sports Med. 2010 Apr;29(2):313-23 Levels of evidence : A

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Robert B. Anderson, MD, Kenneth J. Hunt, MD, Jeremy J. McCormick, MD -Management of Common Sports-related Injuries About the Foot and Ankle, Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 2010; 18: 546-556 Levels of evidence: A

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Lisa Chin, MS, ATC and Jay Hertel, PhD, ATC -Rehabilitation of Ankle and Foot Injuries in Athletes, Clin Sports Med. 2010 Jan;29(1):157-67 Levels of evidence: C

- ↑ Ashman CJ, Klecker RJ, Yu JS.- Forefoot Pain Involving the Metatarsal Region: Differential diagnosis with MR Imaging, Radiographics. 2001 Nov-Dec;21(6):1425-40. Levels of evidence: A

- ↑ Freddie H. FU, M.D , David A.Stone, M.D. –Sports Injuries Mechanisms Prevention Treatment – Williams & Wilkins (1994) p. 620 Levels of evidence: D

- ↑ Thompson FM, Hamilton WG – Problems of the second metatarsophalangeal joint,Orthopedics 10:83, 1987

- ↑ Gerard V.YU, Molly S.Judge, Justin R. Hudson, Frank E. Seidelmann- Predislocation Syndrome Progressive Subluxation/dislocation of the Lesser Metatarsophalangeal JointJournal of the American Podiatric Medical Association 2002 April;92(4): 182- 199 Levels of evidence : A

- ↑ Alfred F. Tallia, MD., M.P.H., and Dennis A. Cardone. D.O., C.A.Q.S.M. -Diagnostic and Therapeutic Injection of the Ankle and Foot, American Academy of family Physicians 2003;68:1356-62 Levels of evidence: A

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Paul K. Canavan – Rehabilitation in Sports Medicine A comprehensive guide – Appleton & Lange (1998) p. 376-377 Levels of evidence : D