Treatment-based Classification System for Low Back Pain

Original Editor - Josh McCormack

Top Contributors - Admin, Kim Jackson, Jess Bell, Robin Tacchetti, Eric Robertson, Josh McCormack, Rachael Lowe, Shaimaa Eldib, Mariam Hashem, Tarina van der Stockt, WikiSysop, Simisola Ajeyalemi, 127.0.0.1 and Evan Thomas

Description[edit | edit source]

Treatment-based classification (TBC) approach to low back pain describes the model whereby the clinician makes treatment decisions based on the patient's clinical presentation[1]. The primary purpose of the TBC approach is to identify features at baseline that predict responsiveness to four different treatment strategies. This approach has been validated[2][3][4][5] and is used widely in the USA.

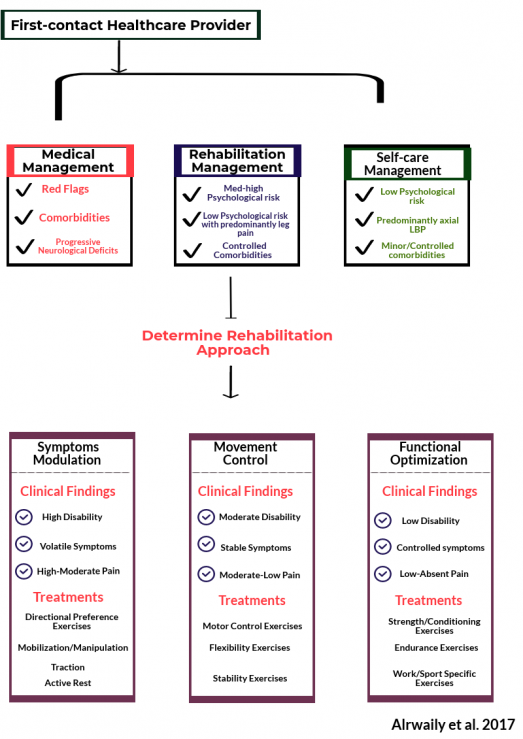

TBC was firstly developed in 1995[6] then updated twice in 2007[7] and 2015[8]. The current TBC has two levels of triage:

- the level of the first contact health care provider

- the level of the rehabilitation provider

First level of Triage - Determining the Management Approach[edit | edit source]

The triage can be assumed by any practitioner competent in LBP care (ie, primary care physician, nurse practitioner, physica therapist, chiropractor). With the responsibility of determining the appropriate approach of management.[9]

Patients with LBP should be triaged using 1 of 3 approaches: medical management, rehabilitation management, or self-care management[9].

Patients requiring medical management are those with red flags of serious pathology (eg, fracture, cancer) or serious co-morbidities that do not respond to standard rehabilitation management (eg, rheumatoid arthritis, central sensitisation).[9]

Clearance of serious pathologies places the patient in either rehabilitation or self-care management. Patients who are amenable to self-care management are those who are unlikely to develop disabling LBP during the course of the current episode. Such patients can be identified using risk profiling instruments such as the STarT Back Tool[10], Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire[11] or similar self-report questionnaires. These patients usually have:

- Low levels of psycho-social distress,

- No or controlled comorbidities,

- Normal neurological status.

They may be treated with patient education that consists of reassurance about the generally favorable prognosis for acute LBP and advice about medication, work, and activity.[12]

The majority of the patients are appropriate for rehabilitation management, as serious pathology is very rare among patients with LBP[13] and patients amenable to self-care management represent a small portion of patients with LBP seen in primary care clinics.[12]

Second Level of Triage - Determining Appropriate Rehabilitation Management[edit | edit source]

When the triage determines that the patient is appropriate for rehabilitation management, the rehabilitation provider should continue to match the patient with 1 of the 3 rehabilitation approaches.[9] The three rehabilitation approaches are: symptom modulation, movement control, or functional optimisation. It is important to realise that these criteria are based on the levels of pain and disability, and the clinician's perception of the overall clinical presentation rather than the number of days[14].

The original classification involved classifying the patient into one of four categories of treatment: "manipulation", "stabilization", "specific exercise" or "traction". These have since been update and modified.

Evaluating the psychosocial status of the patient is important to determine whether a psychologically informed rehabilitation is necessary. Psychosocial status can be assessed using self-report measures (eg, Fear-Avoidance Behavior Questionnaire, STarT Back Tool)[9]

Algorithm (2007)[edit | edit source]

Image:TBC_algorithm-lumbar.jpg

Algorithm (2015):[edit | edit source]

==Symptoms Modulation Approach When patients are presented with the following symptoms/signs, they are best matched to this approach:

- Recent or recurrent episodes of LBP that is currently causing significant symptomatic features

- Patient tend to avoid certain postures

- Active range of movement is limited and painful

- Increased sensitivity with neurological examination

These patients need interventions that modulate their symptoms. In this group, patients are treated mainly with manual therapy, directional preference exercises, traction, or immobilisation.

Movement Control Approach[edit | edit source]

The patient with movement control impairment can fit into one of the following clinical scenarios[15]:

- The first clinical scenario involves sudden new onset of LBP with significant symptomatic features. This clinical presentation should be addressed initially with the symptom modulation approach to lessen the symptom intensity. When the symptoms settle down, some patients continue to experience moderate-to low-level disability that interferes with their ADLs. Although they still have lingering pain and symptoms, it is the functional impairment(s) that dominate the clinical picture. This description meets the criteria of a movement control approach; the patient should be reclassified from symptom modulation into the movement control approach. However, if after the symptom modulating treatment the patient has minimal pain and disability, they may be discharged.[16]

- The second clinical scenario is when the patient does not have any recent history of a significant LBP episode, but rather the symptoms started gradually. For no known reason. The pain is at a low baseline level but could be aggravated by certain ADLs then returns to baseline level when the activity is stopped. For this patient, the impairment of normal activities is more bothersome rather than the pain itself. This type of patient may not benefit from treatments directed only toward symptom modulation. Therefore, the movement control approach should be utilized first without having to pass through the symptom modulation approach. [16]

- Finally, patients may describe recurrent/ repeated episodes of pain that are aggravated with sudden/unexpected movements, but they experience asymptomatic intervals between episodes. These patients may shift between symptom modulation and movement control approaches according to their status at the moment of clinical presentation.[16]

The examination for movement control specifically aims to assess the local mobility and the general stability.

The local mobility examination aims to investigate if lumbar movement is hindered by impairment in the following domains:

- Neural mobility; using neural dynamic assessment such as slump test, straight leg raise test, and femoral nerve tension test. Significant nerve root tension signs suggest that the patient may not be appropriate for the movement control approach instead he/she should be classified into the symptom modulation approach. Alternatively, a patient with impaired neural mobility may receive neurodynamic techniques

- Joint(s) mobility; to investigate whether the lumbar spine and adjacent regions possess proper joint alignment and ability to move freely within physiologic limits. Assessment of joint mechanics involves observing spinal curvatures, alignment relationships, and assessing the mobility of the joints.

- Soft tissue mobility; when soft tissue mobility is impaired, faulty movement compensations and in coordination may result and can possibly leads to injury[17]. Soft tissue mobility impairments can be addressed with various types of manual therapy interventions.

The global stability examination aims to investigate if lumbar movement is impaired by one of the following domains:

- Activation: assesses the ability of an individual muscle to generate isolated contraction and/or a simple movement pattern. Examples of that include abdominal hollowing, scapular retraction, multifidus activation, and breathing pattern.[16]

- Acquisition assesses whether movement is dissociated or coordinated between the lumbar spine and its adjacent regions. Acquisition is tested using basic and advanced motor control abilities (eg, active straight leg raise, active hip extension, active hip abduction). When these abilities are compromised, movement appears discordant between regions.[16]

- Assimilation of movement assesses how newly acquired skills are integrated into ADLs utilising multi-planar movements under dynamic loading conditions. Assimilation is tested by asking the patient to describe activities that aggravate their symptoms. These activities vary with each patient; however, they generally include lifting/lowering, pushing/ pulling, reaching/handling, twisting, and reciprocating. To test how a patient integrates such activities into a daily living function, the rehabilitation provider should simulate these activities in the clinic and plan the rehabilitation strategies accordingly[16].

Alrwaily et al[16] stated that the impairments should be addressed in the following prioritization: neural mobility impairment, joint and soft tissue mobility impairment, motor control impairment, and endurance impairment.

Functional Optimization Approach[edit | edit source]

A functional optimization intervention is for patients who are relatively asymptomatic; they can perform activities of daily living but need to return to higher levels of physical activities (eg, sport, job). The patient’s status is well controlled; that is, the pain is aggravated only by movement system fatigue[9].

These patients need interventions that maximize their physical performance for higher levels of physical activities. For this group, the treatment should optimize the patient’s performance within the context of a job or sport[9].

Clinical Considerations[edit | edit source]

- The 3 rehabilitation approaches are mutually exclusive; however, patients can always be reclassified to receive a different rehabilitation approach as their clinical status changes. For example, a patient who initially receives a movement control approach due to moderate levels of pain and disability can be reclassified to receive a functional optimization approach if his or her status improves to low pain and disability status, or the patient can be reclassified to receive a symptoms modulation approach if his or her status suddenly worsens[9].

- The patient can be discharged at any point when rehabilitation goals are attained.[9]

- Some patient might fit the criteria of 2 or more treatment options, which requires prioritization of treatment. For example, in the symptom modulation approach, a patient may satisfy the criteria for manipulation and extension exercises. In that case, extension exercises take priority over manipulation. Extension exercises should be the treatment of choice until the patient’s status plateaus. At that moment, manipulation may ensue. Similarly, in the movement control approach, a patient may have motor control impairment and reduced muscle performance. In that case, motor control deficit takes priority over the muscle reduced performance. When the control deficit is corrected, muscle performance training can ensue[9].

- When psycho-social factors are high, the rehabilitation provider should educate the patient about pain theory, muscle relaxation techniques, sleep hygiene, and coping skills and address catastrophizing about pain and diagnostic findings[16].

- When medical comorbidities are identified, medical co-management is necessary[9].

Key Evidence[edit | edit source]

Managing individuals with low back pain using a treatment-based classification approach significantly reduces disability and pain compared with current clinical practice guideline standards[18] and enhances clinical decision making[2].

The Reliability of using this approach has been evidenced as good[4] 123 subjects with back pain of fewer then 90 days duration and 30 therapists within varying levels of experience. Overall agreement was 75.9% with a kappa coefficient of .60.

For patients with acute, work-related low back pain, the use of a classification-based approach results in improved disability and return to work status after 4 weeks, as compared with therapy based on clinical practice guidelines. [5] 78 subjects with work-related low back pain randomised to receive treatment based on the TBC or accepted clinical practice guidelines. At 4 weeks there was a significantly greater change in Oswestry scores for the TBC group. At 1 year median total medical costs were 1003.68 for the guidelines group and 774.00 for the classification group.

Brennan et al[3] suggested that outcomes can be improved when subgrouping for low back pain is used to guide treatment decision-making. 123 subjects received care that either matched or did not match their TBC category. Subjects who received matched treatment experienced greater long and short-term improvements in disability versus those who received unmatched treatment.

Presentations[edit | edit source]

Error: Image is invalid or non-existent. |

Treatment Based Classification Approach to Low Back Pain

This presentation, created by Jeff Ryg as part of the Evidence In Motion OMPT Fellowship in 2011, discusses the treatment based classification approach to low back pain and it's implications for research and practice. |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Delitto A, Erhard RE, Bowling RW. A treatment-based classification approach to low back syndrome: identifying and staging patients for conservative treatment. Phys Ther. 1995 Jun;75(6):470-85; discussion 485-9. (level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Hebert JJ1, Koppenhaver SL, Walker BF. Subgrouping patients with low back pain: a treatment-based approach to classification. Sports Health. 2011 Nov;3(6):534-42.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Brennan G, Fritz J, Hunter S, et al. Identifying subgroups of patients with acute/subacute nonspecific low back pain. Spine. 2006;31:623-631 (level of evidence 1B)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Fritz J, Brennan G, Clifford S, et al. [ http://journals.lww.com/spinejournal/Abstract/2006/01010/An_Examination_of_the_Reliability_of_a.18.aspx An examination of the reliability of a classification algorithm for subgrouping patients with low back pain]. Spine. 2006;31:77-82. (Level of Evidence 1B)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Fritz J, Delitto A, Erhard R. Comparison of classification-based physical therapy with therapy based on clinical practice guidelines for patients with acute low back pain. Spine. 2003;28:1363-1372. (Level of evidence 1B)

- ↑ Delitto A, Erhard RE, Bowling RW. A treatment-based classification approach to low back syndrome: identifying and staging patients for conservative treatment. Phys Ther. 1995;75:470 – 485; discussion 485– 479.

- ↑ Fritz JM, Cleland JA, Childs JD. Subgrouping patients with low back pain: evolution of a classification approach to physical therapy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007; 37:290 –302

- ↑ Alrwaily M, Timko M, Schneider M, Stevans J, Bise C, Hariharan K, Delitto A. Treatment-based classification system for low back pain: revision and update. Physical therapy. 2016 Jul 1;96(7):1057-66.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 Therapy, P. (2015). The Treatment-Based Classification System for Low Back Pain : Revision and Update, (December). https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20150345

- ↑ Hill JC, Dunn KM, Lewis M, et al. A primary care back pain screening tool: identifying patient subgroups for initial treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:632–641.

- ↑ Linton SJ, Boersma K. Early identification of patients at risk of developing a persistent back problem: the predictive validity of the O¨ rebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire. Clin J Pain. 2003;19:80–86.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Hill JC, Whitehurst DG, Lewis M, et al. Comparison of stratified primary care management for low back pain with current best practice (STarT Back): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011; 378:1560–1571.

- ↑ Henschke N, Maher CG, Ostelo RW, et al. Red flags to screen for malignancy in patients with low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD008686.

- ↑ Deyo RA, Dworkin SF, Amtmann D, et al. Report of the NIH task force on research standards for chronic low back pain. Spine. 2014;39(14):1128-1143.

- ↑ Dunn KM, Jordan K, Croft PR. Characterizing the course of low back pain: a latent class analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(8):754-761.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 16.7 Alrwaily, M., Schneider, M. J., Bise, C. G., Alrwaily, M., Timko, M., Schneider, M., … Delitto, A. (2017). Treatment-based Classification System for Patients With Low Back Pain : The Movement Perspective Treatment-based Classification System for Patients With Low Back Pain : The Movement Control Approach, (November).

- ↑ Janda V, Frank C, Liebenson C. Evaluation of muscular imbalance. In: Liebenson C, ed. Rehabilitation of the Spine: A Practitioner’s Manual. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1996:97- 112.

- ↑ Scott A. Burns, Edward Foresman, Stephenie J. Kraycsir, William Egan, Paul Glynn, Paul E. Mintken and Joshua A. Cleland. A Treatment-Based Classification Approach to Examination and Intervention of Lumbar Disorders. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach July/August 2011 vol. 3 no. 4 362-372 (Level of Evidence 1B)