Total Hip Replacement: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Kim Jackson (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 276: | Line 276: | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /><br> | <references /><br> | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Orthopaedic Surgical Procedures]] | ||

[[Category:Joints]] | [[Category:Joints]] | ||

[[Category:Hip]] | [[Category:Hip]] | ||

[[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics]] | [[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Vrije Universiteit Brussel Project]] | ||

[[Category:Acute Care]] | [[Category:Acute Care]] | ||

[[Category:Older People/Geriatrics]] | [[Category:Older People/Geriatrics]] | ||

| Line 288: | Line 288: | ||

[[Category:Conditions]] | [[Category:Conditions]] | ||

[[Category:Interventions]] | [[Category:Interventions]] | ||

[[Category:Older People/Geriatrics - Interventions]] | [[Category:Older People/Geriatrics - Interventions]] | ||

[[Category:Older People/Geriatrics - Interventions]] | |||

[[Category:Hip - Interventions]] | |||

[[Category:Osteoarthritis]] | |||

Revision as of 15:12, 22 September 2022

Original Editors - Annelies Beckers, Vincent Everaert

Top Contributors - Lucinda hampton, Annelies Beckers, Leana Louw, Jessie Tourwe, Didzis Rozenbergs, Kim Jackson, Vincent Everaert, Admin, Yana Motte, Scott Buxton, Vidya Acharya, Johnathan Fahrner, Liese Bosman, Rebecca Willis, Liesel Muyelle, George Prudden, Aminat Abolade, Blessed Denzel Vhudzijena, Lauren Lopez, Daniele Barilla, WikiSysop, Heleen.Mergan, Karen Wilson, 127.0.0.1, Kenny Bosmans, Laura Mertens, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Shaimaa Eldib, Evan Thomas, Redisha Jakibanjar and Samuel Adedigba

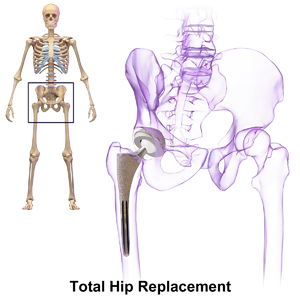

Description[edit | edit source]

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is one of the most cost-effective and consistently successful surgeries performed in orthopaedics.

- THA provides reliable outcomes for patients’ suffering from end-stage degenerative hip osteoarthritis (OA), specifically pain relief, functional restoration, and overall improved quality of life[1]. Once considered a procedure limited to the elderly, low-demand patients, THA is becoming an increasingly popular procedure performed in younger patient populations.[2]

- During a hip replacement, the head of the femur is replaced with a prosthetic head on a shaft, and the joint surface of the acetabulum is lined with a bowl-shaped synthetic joint surface.

- A partial hip replacement can also be done for neck of femur fractures (mostly displaced)[3] where only the femoral part is replaced.

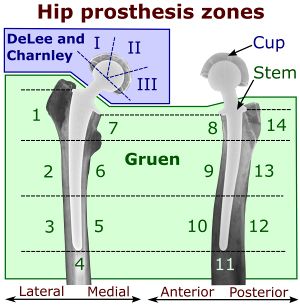

Image 1: Hip prosthesis zones according to DeLee and Charnley, and Gruen. These are used to describe the location of eg areas of loosening.

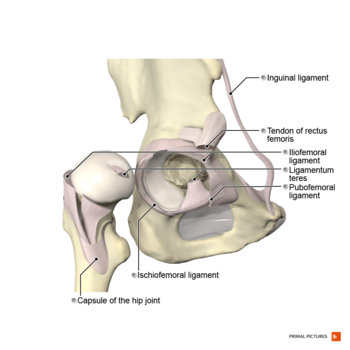

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

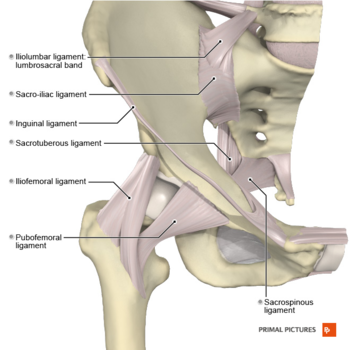

The hip is a ball and socket joint. This design allows the poly-axial movement seen at the hip.

- The ball is the femoral head. The head of the femur is gripped by the acetabulum beyond its maximum diameter.

- The acetabulum (part of the pelvis) is the socket. The acetabulum is cup-shaped, providing the articular surface for the head of the femur to move within.

The head of the femur and the inside of the acetabulum are covered with a layer of hyaline cartilage.[4] Once this cartilage is worn away or damaged (usually by arthritis), the underlying bone is exposed, resulting in pain, stiffness and possibly shortening of the affected leg. By replacing these surfaces the aim is to reduce pain and stiffness to restore an active and pain-free life.

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

Total hip replacement is a frequently done procedure.[5][6][7][8]

- Mostly done electively

- Used to in the management of hip fractures (mostly displaced neck of femur fractures) caused by trauma (e.g. fall) or pathological processes. Osteoporosis and osteomalacia are significant factors responsible for the high incidence of hip fractures within the elderly population.

- Due to the high degree of success at reinstating independence and mobility of osteoarthritis sufferers, total hip replacement procedures have become a well-accepted treatment modality for hip degeneration secondary to osteoarthritis[5][6][7][9][8].

- Also a treatment for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis but only if all the other options have failed[9].

Indications for Surgery[edit | edit source]

The most common indication for THA includes end-stage, symptomatic hip OA. In addition, hip (osteonecrosis) ON, congenital hip disorders including hip dysplasia, and inflammatory arthritic conditions are not uncommon reasons for performing THA. Hip ON, on average, presents in the younger patient population (35 to 50 years of age) and accounts for approximately 10% of annual THAs. Some common indications include:[10]

- Osteoarthritis (see image 4)

- Post-traumatic arthritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis including juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

- Avascular necrosis

- Hardware failure after internal fixation of hip fractures

- Congenital hip dislocations and dysplasia[1]

Contraindications for Surgery[edit | edit source]

THA is contraindicated in the following clinical scenarios:

- Local: Hip infection or sepsis

- Remote (i.e. extra-articularticular) active, ongoing infection or bacteremia

- Severe cases of vascular dysfunction[11]

</article><article></article>

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis of patients requiring total hip replacement surgery is mostly symptom-based. Pain, loss of range of motion and functional impairments are mostly considered.

- A comprehensive differential diagnosis should also be made for patients complaining of hip pain, as it can often be referred from the spine or pelvis and have no connection to the hip joint itself.[9] An orthopaedic surgeon will guide the diagnosis and management process.

See hip examination.

Special Investigations

- X-rays: AP pelvis for hips. This would be the first and, in a lot of cases, only radiological investigations requested, as a lot of the diagnoses in need of a hip replacement can be diagnosed or confirmed by this. This will guide the need for further investigations if needed.[12]

Prosthesis[edit | edit source]

THA prosthetic designs have been evolving since their inception.

Contemporary THA techniques have evolved into press-fit femoral and acetabular components.

Bearing surfaces are the surfaces which articulate in the prosthetic joint. The femoral head and the acetabular liner can be used in different combinations. These will give different appearance on radiograph depending on the configuration. Options for bearing surfaces include:

- Metal-on-polyethylene (MoP): MoP has the longest track record of all bearing surfaces at the lowest cost

- Ceramic-on-polyethylene (CoP): becoming an increasingly popular option

- Ceramic-on-ceramic (CoC): CoC has the best wear properties of all THA bearing surfaces

- Metal-on-metal (MoM): Although falling out of favor, MoM has historically demonstrated better wear properties from its MoP counterpart. MoM has lower linear-wear rates and decreased volume of particles generated. However, the potential for pseudotumor development as well as metallosis-based reactions (type-IV delayed hypersensitivity reactions) has resulted in a decline in the use of MoM. MoM is also contraindicated in pregnant women, patients with renal disease, and patients at risk of metal hypersensitivity.[1]

Femoral component or stem: this refers to the prosthesis which is implanted into the femur. They can be described by length, taper, and presence of a collar. Attached to the femoral component is the neck and head which in most prostheses can be altered in size to create a stable joint[13].

Prosthesis fixation: Femoral stem fixation can be either cemented or non-cemented (biological) fixation. There is a tendency to use non-cemented femoral stems in younger patients, due to higher reported rates of loosening of cemented stems in long term followup. Most common fixation for the acetabular component is non-cemented. Biologic fixation uses either porous coated metallic surface to stimulate bone in growth or grit-blasted surface to allow bone on growth. The prosthesis can also be coated in hydroxyapatite, which is an osteoconductive agent[13].

- Prevalence of fixation technique: increasing trend towards cementless fixation; 93% of THA in United States in 2012 were cementless[14]

Surgical Approaches[edit | edit source]

- Posterior

Most common surgical approach for total hip arthroplasty. Skin incision is made 10-15 cm centred on the posterior aspect of the greater trochanter. Dissection includes splitting fascia lata and gluteus maximus in line with its fibres. This will uncover the short external rotators, which are dissected off the femur and retracted back over the sciatic nerve to protect the nerve throughout the operation. A capsulotomy is then performed and the hip dislocated[13].

2. Direct Anterior (DA)

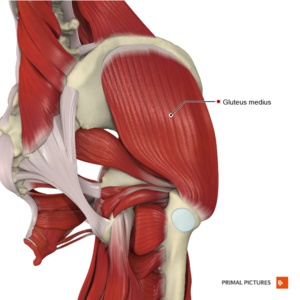

The DA approach is becoming increasingly popular among THA surgeons. The incision is between the tensor fascia lata and sartorius on the superficial end, and the gluteus medius and rectus femoris on the deep side. DA THA advocates cite the theoretical decreased hip dislocation rates in the postoperative period and the avoidance of the hip abduction musculature.

3. Anterolateral (Watson-Jones)

Compared to the other approaches, the anterolateral (AL) approach is the least commonly used approach secondary to its violation of the hip abductor mechanism. The interval exploited includes that of the TFL and gluteus medius musculature. This may lead to a postoperative limp at the tradeoff of a theoretically decreased dislocation rate.

4. Direct lateral (Hardinge)

This approach is also known as the trangluteal approach. Superficial dissection splits the fascia lata to reach the gluteus medius. The superior gluteal nerve enters the gluteal medius muscle belly at approximately 3-5 cm proximal to the greater trochanter. Proximal dissection may result in nerve injury, leading to postoperative Trendelenburg gait, characterized by compensatory movements to address hip abductor weakness. The transgluteal approach has been cited as having the lowest dislocation rate at 0.55%, compared to 3.23% for the posterior approach and 2.18% for the anterolateral approach

- Minimally Invasive Approaches (e.g. direct anterior approach)

The use of minimally invasive surgery is becoming popular all around the world, due to the quicker recovery rates and reduced postoperative pain.[16] Long term follow-up and comparison studies are still needed in this field.

Complications[edit | edit source]

The following are some major complications following THA.

- THA Dislocation About 70% of THA dislocations occur within the first month following index surgery. The overall incidence is about 1% to 3%. Risk factors include: Prior hip surgery (most significant independent risk factor for dislocation); Elderly age (older than 70 years); Component malpositioning: Excessive anteversion results in anterior dislocation and excessive retroversion results in posterior dislocation; Neuromuscular conditions/disorders (for example, Parkinson disease); Drug/alcohol abuse. Recurrent THA dislocations often result in revision THA surgery with component revision[1].

- THA Periprosthetic Fracture. THA periprosthetic fractures (PPFs) are increasing in incidence with the overall increased incidence of procedures in younger patient populations. Intraoperative fractures can occur and involve either the acetabulum and/or femur[1].

- THA Aseptic Loosening. Aseptic loosening is the result of a confluence of steps involving particulate debris formation, prosthesis micromotion, and macrophage activated osteolysis. Treatment requires serial imaging and radiographs and/or CT imaging for preoperative planning. Persistent pain requires revision THA surgery.

- THA Prosthetic Joint Infection (PJI) The incidence of prosthetic total hip infection following primary THA is approximately 1% to 2%. Risk factors include patient-specific lifestyle factors (morbid obesity, smoking, intravenous [IV] drug use and abuse, alcohol abuse, and poor oral hygiene). Other risk factors include patients with a past medical history consisting of uncontrolled diabetes, chronic renal and/or liver disease, malnutrition, and HIV (CD4 counts less than 400).

- Wound Complications. The THA postoperative wound complication spectrum ranges from superficial surgical infections (SSIs) such as cellulitis, superficial dehiscence, and/or delayed wound healing, to deep infections resulting in full-thickness necrosis. Deep infections result in returns to the operating room for irrigation, debridement (incision and drainage) and depending on the timing of the infection, may require explant of THA components[1].

- Venous thromboembnolism events (VTE). Pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT), together referred to as venous thromboembolism (VTE), comprise the most dreaded complications following THA. The median incidence on in-hospital VTE events during the index admission following THA is approximately 0.6%, increasing to up to 2.5% in total joint revision surgeries

- Melallosis. A complication that arises from metal corrosion and release of debris. This causes a massive local cytokine release with resulting inflammation. Systemically it can manifest in many ways. The only treatment is revision surgery.[17]

Other Complications and Considerations

- Nerve injury:[18] Direct lateral approach - superior gluteal nerve, femoral nerve; Direct anterior approach - femoral cutaneous nerve; Posterior approach - sciatic nerve

- Leg Length Discrepancy (LLD)

- Iliopsoas impingement

- Heterotopic ossification

- Vascular injury [1][18][19][20]

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

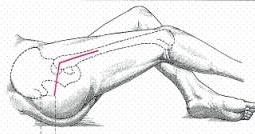

Hip precautions[edit | edit source]

Useful if discussed before surgery.

Types of hip precautions:

Posterolateral approach: avoid

- flexion past 90 degrees

- extreme internal rotation

- adduction past body's midline

Anterolateral approach: avoid[14]

- extension

- extreme external rotation

- adduction past the body's midline

Direct anterior approach: avoid

- bridging

- extension

- extreme external rotation

- adduction past body's midline

Pre-operative[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy: preoperative physical therapy has not been shown to improve postoperative outcomes[14]

- Plays an important role towards improving preoperative quality of life (people can wait many months for surgery and experience further deterioration in health-related quality of life during long waits).[21]

- A 6 week education and exercise programme helps with improvements in pain and disability on patients wait-listed for joint replacement surgery (positive results include improvements in function, knowledge and psycho-social aspects).[22]

Pre-operative assessment and treatment session

- Helps to develop a patient-specific rehabilitation programme to follow post-operative, taking assessment findings into consideration eg Does the patient desires to re uptake golf.

- Benefits: decreased length of stay[23]; decreased anxiety levels[24]; improved self-confidence[25]; establish a relationship of trust between the physiotherapist and patient.

- A combination of verbal explanation and written pamphlets is the best method for health education.[24] Important to incorporate this into the pre-operative physiotherapy management of patients prior to total hip replacements (linked to better post-operative adherence).[24]

Pre op Assessment

- Subjective history

- Range of motion

- Muscle power

- Circulation

- Mobility and function[25]

Pre op Treatment

- Education and advice:

- Patient information booklet

- Precautions and contraindications

- Rehabilitation process

- Goals & expectations

- Functional/ADL adaptions

- Safety principles

- Encourage to stop smoking if applicable

- Discharge planning

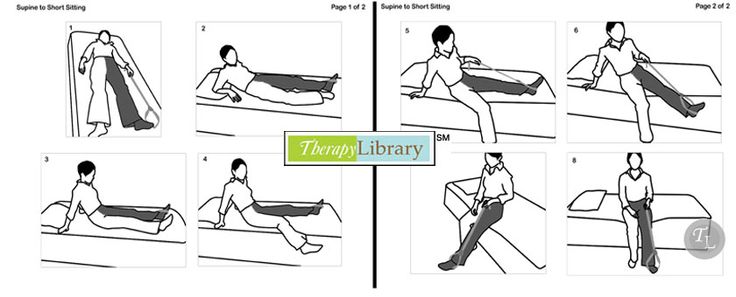

- Teach: Bed exercises; Transfers in and out of bed (within precautions)

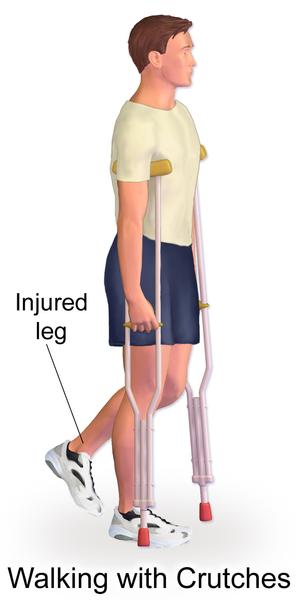

- Gait re-education with mobility assestive device (crutches vs walking frame vs rollator)

- Stair climbing

Post-operative[edit | edit source]

Should start the day of surgery: decrease length of stay; reduces pain and improves function.

- Aim of post-operative rehabilitation: address the functional needs of the patient (e.g. start mobilizing) and to improve mobility, strength, flexibility and reduce pain.[7] . This starts off as an assisted process, but the aim is to get the patient as functional as possible prior to discharge.

- As a result of the underlying pre-operative pathology, patients may present with muscle atrophy and loss of strength, particularly in the gluteus medius and quadriceps muscles. The result of the loss of strength is that the elderly are less independent.[5]

- Surgery will correct the joint problems but associated muscle weakness that was present before the surgery will remain and require post-operative rehabilitation (research has shown hip abductor weakness after surgery is a major risk associated with joint instability and prosthetic loosening).[6] Patients can achieve significant improvements through a targeted strengthening programme following total hip replacement.[26] Motor Imagery training, has been found to be a useful adjunct therapy tool as it improves both specific and general adaptations that were related to patients’ physical capabilities when added in a corollary to routine physical therapy.[27]

- No specific general hip replacement protocol is currently in use, as small elements of the rehabilitation process are surgeon specific. For example, in some enhanced recovery after surgery protocols, patients are mobilised out of bed within the first 6 hours post-surgery. Other settings may only start mobilizing patients out of bed on day 1 or 2 post-surgery. Accelerated rehabilitation programmes and early mobilization have shown to give patients more confidence in their post-operative mobilization and activities of daily living, as well as being more comfortable with earlier discharge.[28]

Evidence[edit | edit source]

- Physiotherapy can improve strength and gait speed after total hip replacement and help prevent complications such as subluxation and thromboembolic disease. In addition, physiotherapy increases the patient’s mobility and offers education about the exercises and precautions that are necessary during hospitalization and after discharge.[29]

- Physiotherapy maximizes the patient’s function which is associated with a greater probability of earlier discharge, which is in turn associated with a lower total cost of care[30]

- Physiotherapy provides pain relief, promotes rehabilitation and the reintegration of patients into ADLs. It also provides a better quality of life through the patients’ reintegration into social life [31]

- Bed exercise following a total hip replacement do not have an effect on the quality of life[32], but important for the effects on oedema, cardiac function and improving range of motion and muscle strength[33]. Allows an assessment of the physical and psychological condition of the patient right after surgery.

- Early weight bearing and physical activity have benefits for the quality of bone tissue[34] as it improves the fixation of the prosthesis and decreases the incidence of early loosening. The amount of activity is patient-specific, and clinical reasoning should be used to make adaptions where needed. Certain specific sport movements have a higher risk of injury for unskilled individuals, and should be incorporated later in the rehabilitation process under supervision of a physiotherapist.

The following is a suggested protocol in the absence of complications. Surgeon preference should be taken into account, as well as any other factors that might hinder the following of the protocol. Adaptions should be made to make it more patient specific.[25][35]

Day 1 Post-Surgery[edit | edit source]

- Education and advice

- Education of muscular relaxation

- Revision of precautions and contraindications (provided that patient had a pre-operative session with the physiotherapist, otherwise full education will be done as mentioned in pre-operative section).

- Bed exercises:

- Circulation drills

- Upper limb exercises to stimulate the cardiac function

- Maintenance of the non-operated leg: attention should be paid to the range of motion in order to preserve controlled mobilisation on the operated hip

- Isometric quadriceps (progressing to consentric VMO) and gluteal contractions

- Active-assisted (progressing to active) heel slides, hip abduction/adduction

- Bed mobilisation using unilateral bridging on the unaffected leg

- Getting in and out of bed (see here)

- Getting on and off a chair with arms (see here)

- Sit to stand with mobility assistive device (preferably a device giving more support like a walking frame or rollator)

- Gait re-education with mobility assistive device as tolerated (weight bearing status as determined by surgeon)

- Sitting out in chair for maximum 1 hour

- Postioning when transferred back to bed

Day 2 Post-Surgery[edit | edit source]

- Bed exercises as described above, progressing repetitions and decreasing assistance given to patient

- Progression of distance mobilised and/or mobility assistive device

- Incorporate balance exercises if needed

- Sitting in chair

Day 3 Post-Surgery[edit | edit source]

Bed exercises as described above, progressing repetitions and decreasing assistance given to patient

- Progression of distance mobilised and/or mobility assistive device

- Stair climbing (at least 3, or as per home requirements)

- Sitting in chair

- Revision of precautions, contraindications and functional adaptions

- Give 6 week progressive resistive strengthening home exercise to patient; this can include stationary cycling, as long as the patient stays within the precautions (especially posterior approach surgery)

After 3 days clients are usually discharged home if fit discharge criteria. The physiotherapist and nurse help to transfer to car maintaining hip precautions. As majority of patients lack understanding about the activities they can do following THR surgery, discharge education about pre-discharge pain management, movement, ADL, and support requirements should be provided to the clients. A recent RCT showed that video-assisted discharge program and education booklets given to the patient and their relatives after THR on activities of daily living, functionality, and patient satisfaction found that video-assisted discharge program along with physiotherapy reduced pain perception and kinesiophobia, improve hip function, and increase patient satisfaction. Further research is needed to assess the long-term outcomes of video-assisted discharge education in THR patients.[36]

Discharge Home Criteria:[edit | edit source]

- independent ambulation with assistive device

- independent transfers

- independent ADLs

- stairs with supervision

- appropriate home assistance (spouse, family, visiting nurses)[14]

Home Planning[edit | edit source]

Several modifications to make home easier to navigate. The following items help with daily activities:

- Securely fastened safety bars or handrails in shower or bath

- Secure handrails along all stairways

- A stable chair for your early recovery with a firm seat cushion (allows knees to remain lower than hips), a firm back, and two arms

- A raised toilet seat

- A stable shower bench or chair for bathing

- A long-handled sponge and shower hose

- A dressing stick, a sock aid, and a long-handled shoehorn

- A reacher allowing grasping of objects without excessive bending of your hips

- Firm pillows for chairs, sofas, and car enabling client to sit with knees lower than hips

- Removal of all loose carpets and electrical cords from the areas walked in home[14]

6 Weeks Post Surgery[edit | edit source]

- Patients are normally followed up by orthopaedic surgeon

- Surgeon determines if the patient is allowed the following:

- Full range of motion at the hip

- Full weight bearing without mobility assistive device

- Driving

After 6 Weeks[edit | edit source]

- Gain of initial ROM, stabilization, and proprioception

- Endurance

- Flexibility

- Balance

- Speed, precision, neurological coordination

- Functional exercises

Return to sport[edit | edit source]

Low-impact exercises are preferred

- golf: handicap shows minimal change after THA; handicap shows increase after TKA

- high-impact exercises increase revision rates in patients less than 55 years-old

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Harris Hip Score

- Oxford Hip Score (OHS)

- 6 Minute Walking Test

- Timed Get Up & Go Test

- Western Ontario and McMaster universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC)

- SF-36

- Fear Avoidance Belief Score

- Hip Disability & Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS)

- International Hip Outcome Tool

- Ibadan Knee/Hip Osteoarthritis Outcome Measure

Team Work[edit | edit source]

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is one of the most reliable, reproducible, successful, and cost-effective procedures in all of orthopedics. The procedure requires coordination of care across various healthcare provider groups, including nurses, physical therapists, advanced practitioners and physician extenders, medical physicians, and orthopedic surgeons.

Clinicians including the surgeon, nurse practitioner, and physician assistant should work together to provide the patient and family with education regarding the procedure, expected issues, and guidance for aftercare.[1]

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Pre-operative patient workbook on "living with osteoarthritis"

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Varacallo M, Luo TD, Johanson NA. Total Hip Arthroplasty Techniques. InStatPearls [Internet] 2020 Jul 8. StatPearls Publishing.Available from: https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/22894/ (accessed 14.2.2021)

- ↑ Levine BR, Klein GR, Cesare PE. Surgical approaches in total hip arthroplasty: A review of the mini-incision and MIS literature. Bulletin of the NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases 2007;65(1):5-18.

- ↑ Iglesias SL, Gentile L, Mangupli MM, Pioli I, Nomides RE, Allende BL. Femoral neck fractures in the elderly: from risk factors to pronostic features for survival. Journal of Trauma and Critical Care. 2017;1(1).

- ↑ Meyers HM. Fractures of the hip. Chicago: Year of the book medical publishers Inc., 1985

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Gremeaux V, Renault J, Pardon L, Deley G, Lepers R, Casillas JM. Low-frequency electric muscle stimulation combined with physical therapy after total hip arthroplasty for hip osteoarthritis in elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 2008;89(12):2265-73.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Jan MH, Hung JY, Lin JC, Wang SF, Liu TK, Tang PF. Effects of a home program on strength, walking speed, and function after total hip replacement. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 2004 ;85(12):1943-51.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Stockton KA, Mengersen KA. Effect of multiple physiotherapy sessions on functional outcomes in the initial postoperative period after primary total hip replacement: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 2009;90(10):1652-7.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Rahmann AE, Brauer SG, Nitz JC. A specific inpatient aquatic physiotherapy program improves strength after total hip or knee replacement surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 2009;90(5):745-55.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Crawford AJ, Hamblen DL. Outline of Orthopaedics , thirteenth edition, London: Churchill Livingstone, 2001

- ↑ Affatato S. Perspectives in total hip arthroplasty: Advances in biomaterials and their tribological interactions. London: Woodhead Publishing, 2014.

- ↑ Varacallo M, Luo TD, Johanson NA. Total Hip Arthroplasty Techniques. InStatPearls [Internet] 2020 Jul 8. StatPearls Publishing.Available from:https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/22894/ (accessed 14.2.2021)

- ↑ Walters J, editor. Orthopaedics - A guide for practitioners. 4th Edition. Cape Town: University of Cape Town, 2010.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Radiopedia THR Available from:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/total-hip-arthroplasty (accessed 14.2.2021)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Ortho bullets THR Available from:https://www.orthobullets.com/recon/5003/tha-implant-fixation (accessed 14.2.2021)

- ↑ Kelmanovich D, Parks ML, Sinha R, MD, Macaulay W. Surgical Approaches to total hip arthroplasty. Journal of the Southern Orthopaedic Association 2003;12:90-94.

- ↑ Alecci V, Valente M, Crucil M, Minerva M, Pellegrino C, Sabbadini DD. Comparison of primary total hip replacements performed with a direct anterior approach versus the standard lateral approach: perioperative findings. J Orthopaed Traumatol 2011;12:123-129.

- ↑ Oliveira CA, Candelária IS, Oliveira PB, Figueiredo A, Caseiro-Alves F. Metallosis: A diagnosis not only in patients with metal-on-metal prostheses. European journal of radiology open. 2015 Jan 1;2:3-6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4750564/ (last accessed 24.2.2019)

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Petis S, Howard JL, Lanting BL, Vasarhelyi EM. Surgical approach in primary total hip arthroplasty: anatomy, technique and clinical outcomes. Can J Surg 2015;58(2):128–139.

- ↑ American Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Total hip replacement. https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/treatment/total-hip-replacement/ (accessed 25/06/2018).

- ↑ Partridge T, Jameson S, Baker P, MBBS, Deehan D, Mason M, Reed MR. Ten-Year Trends in Medical Complications Following 540,623 Primary Total Hip Replacements from a National Database. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2018;100(5):360–367.

- ↑ Gill SD, McBurney H. Does Exercise Reduce Pain and Improve Physical Function Before Hip or Knee Replacement Surgery? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2013;94(1):164-76.

- ↑ Saw MM. The effects of a six-week physiotherapist-led exercise and education intervention in patients with osteoarthritis, awaiting an arthroplasty in the South Africa [dissertation]. Cape Town: University of Cape Town. 2015.

- ↑ Crowe J,Henderson J. Pre-arthroplasty rehabilitation is effective in reducing length of hospital stay. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 2003;70:88-96.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Barnes RY, Bodenstein, K, Human N. Raubenheimer J, Dawkins J, Seesink C, Jacobs J, van der Linde J, Venter R. Preoperative education in hip and knee arthroplasty patients in Bloemfontein. South African Journal of Physiotherapy 2018;74(1).

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Raymond Sohier, Kinesitherapie de la hanche ; La Hestre : Sohier, 1974

- ↑ Galea MP, Levinger P, Lythgo N, Cimoli C, Weller R, Tully E, McMeeken J, Westh R. A targeted home-and center-based exercise program for people after total hip replacement: a randomized clinical trial. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 2008;89(8):1442-7.

- ↑ Paravlic AH, Pisot R, Marusic U. Specific and general adaptations following motor imagery practice focused on muscle strength in total knee arthroplasty rehabilitation: A randomized controlled trial. PloS one. 2019;14(8).

- ↑ Robertson NB, Warganich T, Ghazarossian J, Khatod M. Implementation of an accelerated rehabilitation protocol for total joint arthroplasty in the managed care setting: the experience of one institution. Advances in Orthopedic Surgery. 2015;387197.

- ↑ Coulter CL, Scarvell JM, Neeman TM, Smith PN. Physiotherapist-directed rehabilitation exercises in the outpatient or home setting improve strength, gait speed and cadence after elective total hip replacement: a systematic review. Journal of physiotherapy. 2013;59(4):219-26.

- ↑ Freburger J. An analysis of the relationship between the utilization of physical therapy services and outcomes of care for patients after total hip arthroplasty. Physical therapy 2000;80(5):448-458.

- ↑ Umpierres CS, Ribeiro TA, Marchisio ÂE, Galvão L, Borges ÍN, Macedo CA, Galia CR. Rehabilitation following total hip arthroplasty evaluation over short follow-up time: Randomized clinical trial. Journal of rehabilitation research and development. 2014;51(10):1567-78.

- ↑ Smith TO, Mann CJ, Clark A, Donell ST. Bed exercises following total hip replacement: a randomised controlled trial. Physiotherapy 2008;94(4):286-91.

- ↑ Perhonen MA, Franco F, Lane LD, Buckey JC, Blomqvist CG, Zerwekh JE, Peshock RM, Weatherall PT, Levine BD. Cardiac atrophy after bed rest and spaceflight. Journal of applied physiology 2001;91(2):645-53.

- ↑ Mahendra G, Pandit H, Kliskey K, Murray D, Gill HS, Athanasou N. Necrotic and inflammatory changes in metal-on-metal resurfacing hip arthroplasties: relation to implant failure and pseudotumor formation. Acta orthopaedica 2009;80(6):653-9.

- ↑ Suetta C, Aagaard P, Rosted A, Jakobsen AK, Duus B, Kjaer M, Magnusson SP. Training-induced changes in muscle CSA, muscle strength, EMG, and rate of force development in elderly subjects after long-term unilateral disuse. Journal of Applied Physiology 2004;97(5):1954-61.

- ↑ Cetinkaya Eren O, Buker N, Tonak HA, Urguden M. The effect of video-assisted discharge education after total hip replacement surgery: a randomized controlled study. Scientific Reports. 2022 Feb 23;12(1):1-9.