Tinnitus

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

‘Tinnitus’ is defined as the perception of sound in the absence of corresponding external acoustic stimuli.[1]

A difference exists between subjective and objective tinnitus. Subjective (somatic) tinnitus is a phantom phenomenon and is heard only by the patient. Objective tinnitus can be described as a condition in which noises are generated within the body and transmitted to the ear, e.g., via spasms of the tensor muscle of the tympanic membrane[1] .It is audible to another person, as a sound stemming from the ear canal.[2]

Severe tinnitus is associated with depression, anxiety and insomnia.[3]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

A neural connection between the somatosensory and the auditory systems may be important in tinnitus. Anatomical and physiological evidence support this statement. The trigeminal and dorsal root ganglia transfer afferent somatosensory information from the periphery to secondary sensory neurons in the brainstem. These structures send excitatory projections to the cochlear nucleus. Moreover, the cochlear nucleus innervates parts of the trigeminal, ophthalmic and mandibular nuclei. Signals from the trigeminal supply the hearing system in the cochlear nucleus, superior olivary nucleus, and inferior colliculus.[4]

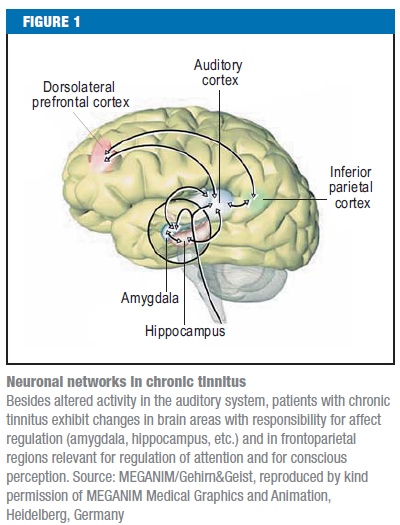

Patients with chronic tinnitus exhibit changes in brain areas with responsibility for affect regulation (amygdala, hippocampus, etc.) and in frontoparietal regions relevant for regulation of attention and for conscious perception.[1]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Between 5% and 15% of the general population report tinnitus which has major negative impact on quality of life, in 1% of these specific tinnitus population,. [1][4][3]

Tinnitus is multifaceted with a variety of causes: otological, neurological, metabolic, pharmacological, vascular, musculoskeletal and psychological.[4]

Despite the fact that tinnitus is often seen in connection with hearing impairment, not all patients have impaired hearing.[4]

Subjective tinnitus is a phantom phenomenon. An example of a phantom phenomenon is acoustic hallucination which is particularly in patients with schizophrenia or after consumption of hallucinogenic substances.[1]

Somatic (subjective) tinnitus has also been associated with musculature and joint pathologies (for instance facet arthropathy[1][5]) of the neck, and disorders of the temporomandibular joint.[4][5][2] (Link)

In Latifpour DH et al, 2009 the relationship between the somatosensory system, disorders/dysfunction of head and neck and tinnitus is described. Aggravation of tinnitus can be caused by disorders of the somatosensory system of the upper cervical region and head. Dysfunction of the head and upper-neck region can cause tinnitus via activation of the somatosensory system. Strong muscle contractions of the head and neck can modulate the tinnitus perception of 80% of tinnitus patients and elicit a sound perception in 50% of people without tinnitus.

These somatic phenomena are equally spread among people with or without a disorder of the cochlea. A clear connection can also be seen between jaw disorders, neck pain, headache, and tinnitus. There could also be a connection between nerve impulses from the back of the neck and head through multisynaptic connections in the brainstem and cochlea.[4]

A dominant finding in a study of Reisshauer et al, 2006 is an overall impairment of cervical spine mobility, to which various factors contribute. These include disturbed function of segmental joints of the head and the cervicothoracic junction as well as muscular imbalances of the shoulder and neck muscles (the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the descending part of the trapezius muscle, the levator muscle of the scapula and the masseter muscle)[6]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Patients with tinnitus hear noises in absence of a corresponding external acoustic stimulus. Tinnitus consists of unorganized acoustic impressions of various kinds. The ear noise may be perceived as unilateral, bilateral or arising in the head.[1]

In case of objective tinnitus, the sound can be heard by another person.

On the other hand, somatic tinnitus in association with disorders of the head and neck, the sound is specifically localized to the ear ipsilateral to the somatic dysfunction along with no vestibular complaints and no abnormalities on neurologic exam. [2]

In case of subjective tinnitus, patients can have acoustic hallucinations and tend to involve the perception of sounds in organized form, such as music or speech.[1]

A distinguish can also be made between pulsatile and non-pulsatile tinnitus. Pulsatile tinnitus is synchronized with the heartbeat and can be a symptom of vascular malformations.

Tinnitus can also appear as an extensive fluctuating tinnitus.[4] In this case the ear noise can be modulated by movements of the jaw or cervical spine.[1]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

add text here

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Flowchart Chronic tinnitus[1]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

add links to outcome measures here (also see Outcome Measures Database)

Examination[edit | edit source]

In every case of tinnitus the following features must be determined:

- Duration of the tinnitus (acute versus chronic)

- Pulsatility

- Modulation of the tinnitus

- Attendant symptoms such as sleep disorders and concentration problems

In case where the ear noise can be modulated by movements of the jaw or cervical spine physiotherapy or examination by an orthopedist/orthodontist should be considered. Magnetic resonance imaging to exclude a vestibular schwannoma is recommended in patients with unilateral tinnitus and a distinct right-left discrepancy in hearing acuity.

Pulsatile tinnitus is synchronized with the heartbeat and can be a symptom of vascular malformations. These patients should be referred to a doctor for neuroradiological examination.[1]

In patients with somatically related tinnitus it is appropriate to examine:

1) The mobility of neck flexion and extension, lateral flexion right and left, rotation right and left by using an inclinometer. The measurement is performed in a sitting position and the best value of three is noted.

2) Posture by using a kyphometer. The measurement is performed in a standing position. The thoracic kyphosis is measured from C7-T12 and the lumbar lordosis from T12-L5.[4]

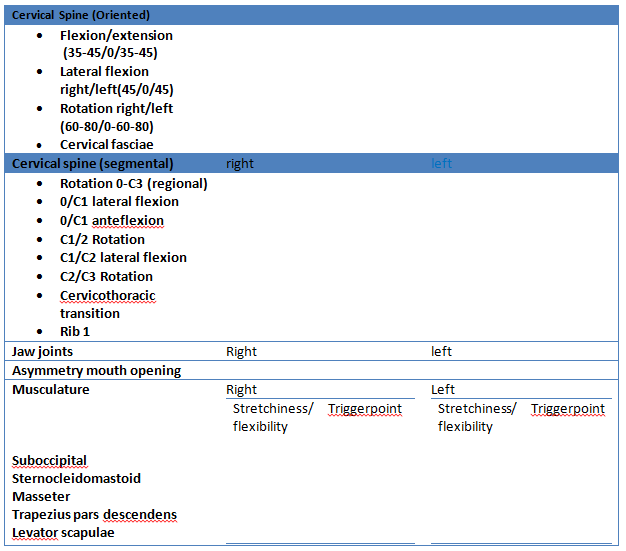

In a study from Reisshauer et al, 2006 the examination protocol consisted of global and segmental joint mobility of the cervical spine, cervicothoracic junction, first rib, craniomandibular system, muscle extensibility and trigger points for the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the descending part of the trapezius muscle, the levator muscle of the scapula and the masseter muscle. [6]

Table: Standardized examination protocol for management of patients with tinnitus[6]

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

No medicinal approach can yet be regarded as an established treatment option. Accordingly, neither in Europe nor in the USA has any drug yet been approved for the treatment of tinnitus. The indication for pharmacotherapy is therefore restricted to the treatment of comorbidities such as anxiety disorders, sleep disorders, and depression.[1]

Gritsenko et al., 2014 describes in a case report of a 65 year old man in which is diagnosed a facet arthropathy of C2-C3, a successful treatment by applying a medical branch block of C2-C3 in combination with radiofrequency ablation of C2-C3 medial branches.[2]

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

Up until now 5 methods has been found to be effective as a treatment for tinnitus.

- Cervical movements and muscle contractions

Performing a series of repetitive cervical movements and muscle contractions of the neck has been proven to be successful in treating cervical tinnitus. [5][7] The chosen movements should have as purpose normalizing cervical spine mobility.[5] There is evidence that performing cervical movements and muscle contractions modulates tinnitus more frequently than it generates or aggravates tinnitus. [8]

Cherian K et al. who performed a similar therapy, found a complete reversal of tinnitus after 2,5 months of exercises and noticed a significant improvement of the cervical motion. [5] Sanchez TG et al. also noted that maneuvers of the head and neck muscle contractions evoked tinnitus modulation in a frequent and reliable manner after two months. The tinnitus worsening decreased and the improvement increased although the daily perception remained unchanged. [7]

- Stretching, postural training and acupuncture

Stretching, posture training and auricular acupuncture also decreases significantly tinnitus up to 3 months after the treatment. It is recommended to stretch the tense muscles of the neck and shoulders, like m. sternocleidomastoideus, m. trapezius, m. levator scapulae, m. suboccipitalis …[4] This method is based on somatosensory stimulation and it may be useful as an alternative treatment.

- TENS

TENS can also be effective when applied to either skin areas close to the ear or to the upper cervical nerve C2, but it depends on the patients.[9][10]Vanneste S.et al. found an improvement of 42,92% and a full reduction of the symptoms in 6 cases, but only 17,9% of their 42 cases responded to the C2 TENS[10]

- Qigong

Finally, Qigong has been proven to be an effective way of treating tinnitus. No side-effects have been shown, there is a significant improvement in somatic tinnitus severity and the effects remain stable for at least 3 months after the last session.[3]

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the best-evaluated treatment for chronic tinnitus. The general aim of CBT in patients with tinnitus is to improve awareness and facilitate the modification of maladaptive patterns on the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral level.[1]

Key Research[edit | edit source]

add links and reviews of high quality evidence here (case studies should be added on new pages using the case study template)

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 Kreuzer PM, Vielsmeier V, Langguth B. Chronic tinnitus: an interdisciplinary challenge. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013 Apr;110(16):278-84 (Level of evidence 2A)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Gritsenko K, Caldwell W, Shaparin N, Vydyanathan A, Kosharskyy B. Resolution of long standing tinnitus following radiofrequency ablation of C2-C3 medial branches--a case report. Pain Physician. 2014 Jan-Feb;17(1):E95-8 (Level of evidence 3B)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Biesinger E, Kipman U, Schätz S, Langguth B. Qigong for the treatment of tinnitus: a prospective randomized controlled study. J Psychosom Res. 2010 Sep;69(3):299-304 (Level of evidence 1B)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Latifpour DH, Grenner J, Sjödahl C. The effect of a new treatment based on somatosensory stimulation in a group of patients with somatically related tinnitus. Int Tinnitus J. 2009;15(1):94-9 (Level of evidence 1B)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Cherian K, Cherian N, Cook C, Kaltenbach JA. Improving tinnitus with mechanical treatment of the cervical spine and jaw, J Am Acad Audiol, 2013 Jul-Aug;24(7):544-55, (Level of evidence 3B)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Reisshauer A, Mathiske-Schmidt K, Küchler I, Umland G, Klapp BF, Mazurek B. Functional disturbances of the cervical spine in tinnitus]. HNO. 2006 Feb;54(2):125-31 (level of evidence 2C)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Sanchez TG, da Silva Lima A, Brandão AL, Lorenzi MC, Bento RF. Somatic modulation of tinnitus: test reliability and results after repetitive muscle contraction training, Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, 2007 Jan;116(1):30-5, (level of evidence 1B)

- ↑ Sanchez TG, Guerra GC, Lorenzi MC, Brandão AL, Bento RF , The influence of voluntary muscle contractions upon the onset and modulation of tinnitus, Audiol Neurootol, 2002 Nov-Dec;7(6):370-5, (level of evidence 2B)

- ↑ Herraiz C, Toledano A, Diges I. Trans-electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for somatic tinnitus. Prog Brain Res. 2007;166:389-94. (Level of evidence 1B)

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Vanneste S, Plazier M, Van de Heyning P, De Ridder D. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) of upper cervical nerve (C2) for the treatment of somatic tinnitus. Exp Brain Res. 2010 Jul;204(2):283-7. (Level of evidence 1B)