Therapeutic Alliance

Original Editor - Laura Ritchie, posting on behalf of Wei Seah, MPT Class of 2017 at Western University, project for PT9584.

Top Contributors - Laura Ritchie, Kim Jackson, Mandy Roscher, Ewa Jaraczewska, Wanda van Niekerk, Naomi O'Reilly, Jess Bell, Robin Tacchetti, Evan Thomas and Vidya Acharya

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The therapeutic alliance (also referred to as the working alliance) is a description of the interaction between the physiotherapist and their patients. By establishing a therapeutic alliance, the therapist then seeks to provide patient-centered care, in which the therapist is seen as a facilitator for the patient to achieve their goals, rather than an authority figure.[1] Previous research has highlighted the importance of providing patient-centered care not only in physiotherapy, but other medical professions as well. [2] This is accomplished by encouraging the patient to become more active in their treatment to engage them in a collaborative, active approach to recovery.[3] By establishing a strong therapeutic alliance and encouraging patient participation, therapists can also seek to address psychosocial aspects of pain, [4] which are often overlooked in traditional unidirectional patient-therapist interactions. This is especially important as recent research supports that the physical treatment alone cannot fully account for the improvement of patient outcomes. [5]

Background[edit | edit source]

The therapeutic alliance was first described by Freud in 1912, in which he outlined the concepts of transference and countertransference, which are the unconscious feelings or emotions that a patient feels towards their therapist, and vice-versa. [6] Further research by Rogers (1951) was the first to highlight empathy as a core characteristic of this therapeutic alliance and Anderson (1962) conceptualized both empathy and rapport as qualities within the “therapeutic bond”.[7] [8] Hougaard (1994) consolidated previous data into a conceptual structure composed of two branches, the personal relationship area and the collaborative area. [9]The personal relationship area focuses on the socio-emotional aspect of the therapist-patient relationship, while the collaborative relationship area consists of more task-related aspects, such as goal-setting and treatment planning. It was Martin, Garske and Davis (2000) concretely described the therapeutic alliance as “…the collaborative and affective bond between therapist and patient – is an essential element of the therapeutic process.” [10]

Components of a Therapeutic Alliance[edit | edit source]

Bordin[11] describes the 3 components that contribute to a strong therapeutic alliance are

- Agreement on goals (Collaborative Goal Setting)

- Agreement on interventions (Shared Decision Making)

- Effective bond between patient and therapist (The Therapeutic Relationship)

Collaborative Goal Setting[edit | edit source]

Goal setting serves a fundamental role in guiding rehabilitation so that a specific outcome is reached. Setting SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant and Time Limited) goals is a useful way to ensure goals are successful.

The agreement of goals between the patient and the therapist increases adherence to those goals which in turn leads to improved outcomes.[12] It improves patient satisfaction as well as motivation. All of these factors positively influence the therapeutic alliance.[12] When patients are excluded from this process and goals are simply set for them, it creates a situation of dissatisfaction which will negatively influence the therapeutic alliance[12]

[edit | edit source]

Shared decisions help to strengthen the therapeutic alliance.[12] It is a process of providing the patient with information and supporting them through the decision making process.[13]

A process for shared decision making is outlined by Elwyn et al[13] whereby you move through a 3 step approach

- Choice Talk

- Step back

- Offer Choice

- Justify Choice- consider preferences

- Check Reaction

- Defer Closure

- Option Talk

- Check knowledge

- List Options

- Describe Options - explore preferences

- Harms and Benefits

- Provide patient decision support

- Summarize

- Decision Talk

- Focus on preferences

- Elicit preferences

- Move to a decision

- Offer review

The Therapeutic Relationship[edit | edit source]

The Therapeutic relationship refers to the professional bond between the therapist and patient. It is the key component of a strong therapeutic alliance.

The following components contribute to the development of a strong therapeutic relationship [12]

- Communication Skill

- Active listening

- Empathy

- Friendliness

- Encouragement

- Confidence

- Non-Verbal communication

- Practical Skills

- Patient education that is simple and clear

- Therapist expertise and training

- Patient-Centred Care

- Individualised treatments

- Taking patients opinions and preferences into consideration

- Organisational and Environmental Factors

- Giving patients enough time for thorough assessment and management

- Flexibility with patient appointments and care

Patient-Centred Care[edit | edit source]

Good communicative skills are an integral tool to achieving a strong therapeutic alliance and research has shown that effective communication also leads to increased patient adherence and satisfaction. [14] Mead and Bower (2000) [2] identified five key dimensions of patient-centered care which have been associated with a positive therapeutic alliance: [15]

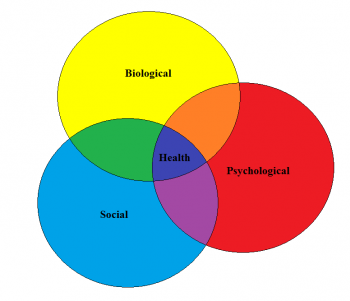

1. Utilizing a biopsychosocial perspective:[edit | edit source]

Several conditions treated by physical therapists appear to have little relation to structural or physiological changes, which can themselves be interpreted with high variability. [16] [17] [18] Thus, an approach that considers not only biological, but also psychological and sociological factors as well, is needed to appreciate the full scope of the problems presented and provide patient-centered care. [19]

2. The ‘patient-as-person':[edit | edit source]

Although the biopsychosocial model seeks to address all of the factors surrounding the patient, it may not be sufficient to fully appreciate the patient experience. [20] We need to understand that each patient may perceive the same pain experience differently and that eliciting the individual patient’s fears, expectations and feelings of illness should be one of our primary concerns [21]

3. Sharing power and responsibility:[edit | edit source]

The patient-practitioner relationship has always been fundamentally seen as a ‘paternalistic’ relationship, which some see as an inevitability due to the competence gap between them. [22] By shifting patients from ‘consumers’ to active ‘participants’, we can help place patients in control of their own illness, and this has been correlated with better health outcomes. [23]

4. The therapeutic alliance:[edit | edit source]

Just as patient-centered care can strengthen the therapeutic alliance, the reciprocal relationship can also occur. As mentioned above Bordin (1979) described the three main components of the therapeutic alliance as 1) agreement on goals, 2) agreement on interventions, 3) effective bond between patient and therapist. [11]

5. The ‘doctor-as-person’:[edit | edit source]

Since both the therapeutic alliance and patient-centered care acknowledge the relationship between both therapist and patient, it is thus logical to also place importance of the qualities of the therapist. The interaction between therapist and patient is constant, and the subjectivity of the therapist is something that cannot be separated from this interaction. [24]

Effect on Patient Outcomes[edit | edit source]

The therapeutic alliance has previously been shown to improve patient outcomes in both medicine as well as psychology. [25] [26] [27] [28] It is only recently that investigation has been made into its effects in other rehabilitative sciences. Burns and Evon (2007) studied its effect in cardiac rehabilitation and found that increased self-efficacy is not enough of a factor to predict increase cardiorespiratory fitness, weight reduction and return to work. [29] Instead, it must be combined with a strong therapeutic alliance to achieve these outcomes, and a poor therapeutic alliance can undermine the potential for improvement. Ferreira and colleagues (2012) examined the relationship between therapeutic alliance and patient outcomes on rehabilitation of patients with chronic low back pain. [30] They found that a strong therapeutic alliance leads to increased perceived changes following a variety of conservative treatments. Interestingly, a strong therapeutic alliance was associated with improved disability and function outcome measures, but not pain. Fuentes et al (2013) also conducted a study utilizing patients with low back pain, this time measuring the therapeutic alliance’s effect on pain intensity and muscle pain sensitivity. [31] The results showed that a strong therapeutic alliance can significantly modify perceived pain intensity after IFC treatments, which are displayed below. Another point of interest is the active IFC with limited therapeutic alliance was not statistically different than a sham IFC with a strong therapeutic alliance.

A systematic review of the impact of the therapeutic alliance in physiotherapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain found that a significant impact of the therapeutic alliance on patient outcomes[32]. It recommends communication training in healthcare professionals as a way of improving the therapeutic alliance as well as encouraging patient-therapist collaboration in treatment decisions.

Measuring the therapeutic alliance[edit | edit source]

Popular outcome measures for the therapeutic alliance include the Working Alliance Theory of Change Inventory, which itself is derived from the Working Alliance Inventory. [33] Hall et al (2011) found that there was some room for improvement in the WATOCI, specifically relating to the wording in certain sections. [34] The nine items that remained were found to be a uni-dimensional tool for measuring the therapeutic alliance, despite demonstrating a ceiling effect. Due to the complexity of the therapeutic alliance it may be difficult to find a perfect measurement, however patient-administered outcomes are a step in the right direction as patient perception of the therapeutic alliance has been found to be a better predictor of outcome than therapist perception. [35]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Walton D, Dhir J, Millard J. Introduction and Application of the CARE Model in Physiotherapy Practice. Presentation presented at; 2016; London, Ontario, Canada

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;51(7):1087-1110.

- ↑ Epstein R, Street R. The Values and Value of Patient-Centered Care. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2011;9(2):100-103

- ↑ Gatchel R, Peng Y, Peters M, Fuchs P, Turk D. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: Scientific advances and future directions. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133(4):581-624.

- ↑ Ambady N, Koo J, Rosenthal R, Winograd C. Physical therapists' nonverbal communication predicts geriatric patients' health outcomes. Psychology and Aging. 2002;17(3):443-452.

- ↑ Freud S. The Dynamics of Transference. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. 1912;XII (1911-1913):97-108.

- ↑ Rogers C. Client-centered therapy. 1st ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 1951

- ↑ Anderson R, Anderson G. Development of an instrument for measuring rapport. The Personnel and Guidance Journal. 1962;41(1):18-24

- ↑ Hougaard E. The therapeutic alliance–A conceptual analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 1994;35(1):67-85.

- ↑ Martin D, Garske J, Davis M. Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(3):438-450

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Bordin E. The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 1979;16(3):252-260

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 O'keeffe M, Cullinane P, Hurley J, Leahy I, Bunzli S, O'sullivan PB, O'sullivan K. What influences patient-therapist interactions in musculoskeletal physical therapy? Qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis. Physical therapy. 2016 May 1;96(5):609-22.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Kinnersley P, Cording E, Tomson D, Dodd C, Rollnick S, Edwards A. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. Journal of general internal medicine. 2012 Oct 1;27(10):1361-7

- ↑ Gyllensten A, Gard G, Salford E, Ekdahl C. Interaction between patient and physiotherapist: a qualitative study reflecting the physiotherapist's perspective. Physiotherapy Research International. 1999;4(2):89-109.

- ↑ Pinto R, Ferreira M, Oliveira V, Franco M, Adams R, Maher C et al. Patient-centred communication is associated with positive therapeutic alliance: a systematic review. Journal of Physiotherapy. 2012;58(2):77-87.

- ↑ Rogers A, Nicolaas G, Hassell K. Demanding patients?. 1st ed. Buckingham [etc.]: Open University Press; 1999

- ↑ Deyo R, Weinstein J. Low Back Pain. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344(5):363-370

- ↑ Herzog R, Elgort D, Flanders A, Moley P. Variability in diagnostic error rates of 10 MRI centers performing lumbar spine MRI examinations on the same patient within a 3-week period. The Spine Journal. 2017;17(4):554-561

- ↑ Silverman D. Communication and medical practice. 1st ed. Inglaterra: Sage Publications; 1987.

- ↑ Armstrong D. The emancipation of biographical medicine. Social Science and Medicine Part A: Medical Psychology and Medical Sociology. 1979;13:1-8

- ↑ Levenstein J, McCracken E, McWhinney I, Stewart M, Brown J. The Patient-Centred Clinical Method. 1. A Model for the Doctor-Patient Interaction in Family Medicine. Family Practice. 1986;3(1):24-30

- ↑ Parsons T, Smelser N. The social system. 1st ed. New Orleans, La.: Quid Pro Books; 2012

- ↑ Kaplan S, Greenfield S, Ware J. Assessing the Effects of Physician-Patient Interactions on the Outcomes of Chronic Disease. Medical Care. 1989;27(Supplement):S110-S127

- ↑ Balint E., Courtenay M., Elder A., Hull S., Julian P. The doctor, the patient and the group: Balint re-visited. 1st ed. London: Routledge; 1993

- ↑ Kao A, Green D, Davis N, Koplan J, Cleary P. Patients’ trust in their physicians. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1998;13(10):681-686

- ↑ Bachelor A. Comparison and relationship to outcome of diverse dimensions of the helping alliance as seen by client and therapist. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 1991;28(4):534-549

- ↑ Barber J, Connolly M, Crits-Christoph P, Gladis L, Siqueland L. Alliance predicts patients' outcome beyond in-treatment change in symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(6):1027-1032

- ↑ Gaston L, Piper W, Debbane E, Bienvenu J, Garant J. Alliance and Technique for Predicting Outcome in Short-and Long-Term Analytic Psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research. 1994;4(2):121-135

- ↑ Burns J, Evon D. Common and specific process factors in cardiac rehabilitation: Independent and interactive effects of the working alliance and self-efficacy. Health Psychology. 2007;26(6):684-692

- ↑ Ferreira P, Ferreira M, Maher C, Refshauge K, Latimer J, Adams R. The Therapeutic Alliance Between Clinicians and Patients Predicts Outcome in Chronic Low Back Pain. Physical Therapy. 2012;93(4):470-478

- ↑ Fuentes J, Armijo-Olivo S, Funabashi M, et al. Enhanced therapeutic alliance modulates pain intensity and muscle pain sensitivity in patients with chronic low back pain: an experimental controlled study. Phys Ther. 2013;94:477-489

- ↑ Kinney M, Seider J, Beaty AF, Coughlin K, Dyal M, Clewley D. The impact of therapeutic alliance in physical therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review of the literature. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2018 Sep 24:1-3

- ↑ Horvath A, Greenberg L. Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1989;36(2):223-233

- ↑ Hall A, Ferreira M, Clemson L, Ferreira P, Latimer J, Maher C. Assessment of the therapeutic alliance in physical rehabilitation: a RASCH analysis. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2011;34(3):257-266

- ↑ Castonguay L, Constantino M, Holtforth M. The working alliance: Where are we and where should we go?. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2006;43(3):271-279