The Theory and Practice of Massage and Exercise for Plantar Heel Pain

Original Editor - Merinda Rodseth based on the course by

Bernice Saban

Top Contributors - Merinda Rodseth, Kim Jackson, Wanda van Niekerk, Jess Bell and Ewa Jaraczewska

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Manual therapy is commonly used by physiotherapists to improve mobility and reduce pain.[1] Myofascial restrictions of the posterior calf muscles have been implicated in the development of plantar heel pain (PHP) as they interfere with the extensibility of the muscles and fascia, thus impeding optimal muscle functioning.[2][3] The manual therapy discussed in the “new protocol” for plantar heel pain syndrome (PHPS) refers to Deep Friction Massage therapy, which is based on the teachings of Dr James Cyriax.[4]

Dr Cyriax's teachings are based on three principles:[5]

- All pain arises from a lesion

- All treatment must reach the lesion

- All treatment must have a beneficial effect on the lesion

The two attributes of muscles that enable them to function effectively include the ability to:[5]

- Contract - shorten and widen

- Relax - lengthen and narrow

Damage to the muscle during injury can disrupt both of these attributes and prevent optimal contraction (widening) and relaxation (lengthening). Following trauma, where there is damage to the muscle, healing occurs. During healing, scar tissue forms. Scar tissue is less elastic and more fibrous than muscle tissue.[6] It is also prolific and attaches to the adjacent muscle fibres that are not damaged. This can cause pain and limited movement because of the adhesions between the muscle fibres.

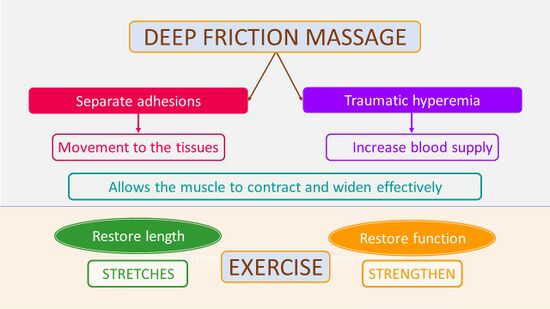

Deep friction massage helps to separate these adhesions to create movement in the tissues while simultaneously causing traumatic hyperaemia, which stimulates blood supply and promotes healing (Figure 1).[5][7][8] Massage supports the muscle to contract and widen effectively by breaking down any adhesions between the muscle fibres.

Figure 1. Impact of Deep Friction Massage and Exercise [5]

Because both muscles and fascia are implicated in PHPS,[2] it is important that muscle fibres are lengthened. This can be achieved through the disruption of adhesions, as well as the use of stretches. Stretches have been shown to be beneficial for patients with PHPS, but not as a stand-alone treatment as they only address one aspect of the muscle’s functioning - i.e. its ability to lengthen.[9] Deep friction massage compliments the use of stretching, enabling the muscle to recover its ability to contract.

Deep Friction Massage of the Posterior Calf Muscles[edit | edit source]

Deep Friction Massage (DFM) was developed by Dr Cyriax as a technique to stimulate the regeneration process of the soft tissues.[10] DFM involves passive mobilisation of the soft tissues to:[10]

- Enhance fibroblastic activity

- Break disorganised and dysfunctional adhesions between collagen fibres

- Realign and elongate collagen fibres

- Decrease pain

- Re-establish blood supply

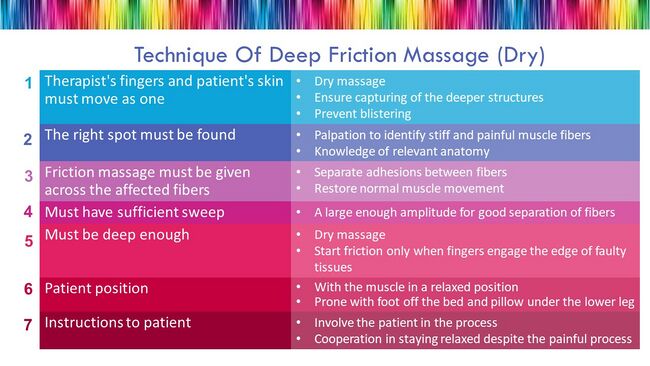

In order to maximise the effects of DFM, it is necessary to adhere to the basic principles of application provided by Dr Cyriax (Figure 2).[5][7][10]

Figure 2. The Principles of Application of Deep Friction Massage [5]

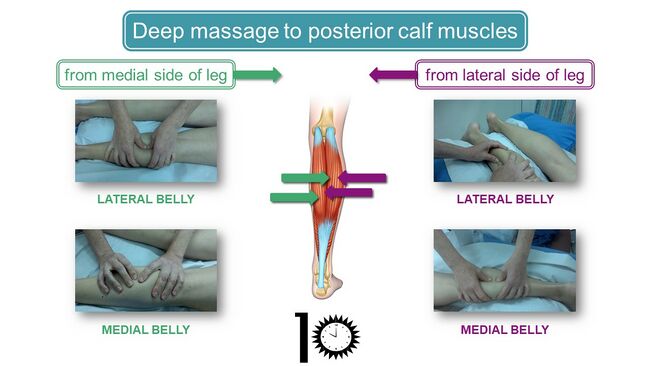

The approach to the DFM of the posterior calf muscles should be systematic, ensuring that all tight parts of the posterior calf muscles are identified and treated. One systematic approach is to start on the (Figure 3): [5]

- Lateral side of the leg

- Place the thumbs on the lateral border of the lateral belly of the gastrocnemius muscle assessing for tightness not only in the superficial gastrocnemius muscle, but also the deeper muscles

- Move fingers to the lateral border of the medial belly in the centre of the calf

- Medial side of the leg

- Place fingers on the medial border of the lateral belly

- Move fingers to the medial border of the medial belly

Move down the length of the muscles on both sides of the leg, starting proximally at the popliteal fossa and moving distally to the sides of the Achilles tendon in order to identify all painful and incompliant areas. Treatment should be continued for at least 10 minutes.[5]

Figure 3. Approach to the deep massage of the posterior calf muscles [5]

More force might be necessary for patients with exceptionally stiff or developed muscles. Start by using the fingers to locate the incompliant areas and continue to treat using the elbow in order to generate more force and penetrate at a sufficient depth (Figure 4).[5]

Figure 4. Deep Friction Massage of the Calf using the Elbow [5]

Following the dry DFM, continue with: [5]

- A massage with cream/oil to locate additional stiff areas

- Skin rolling

Massage is a safe technique that is widely used for the treatment of soft tissues. It is, however, important to keep some contraindications to massage in mind:[5][11]

- Fever

- Under the influence of alcohol or drugs, including prescription medication

- Skin diseases/lesions

- Contagious diseases

- Unusual and undiagnosed lumps or bumps

- Undiagnosed pain

- Cuts

- Sunburn

- Varicose veins - it might be beneficial for venous return to work around the varicose veins, but avoid working over the swollen veins themselves

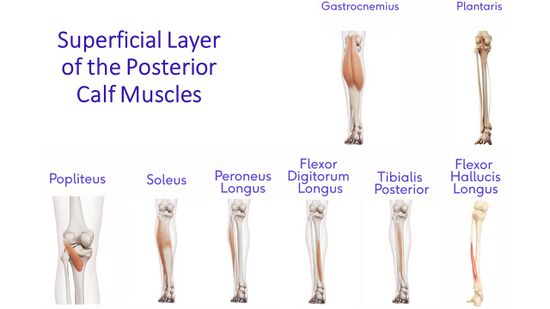

Keep in mind the anatomy of the muscles of the posterior calf when considering DFM.[5]

The superficial layer of the posterior calf (Figure 5):

- Medial and lateral heads of the gastrocnemius muscle

- Plantaris (with its belly crossing the popliteal fossa)

- Popliteus

- Soleus

- Peroneus longus

- Flexor digitorum longus

- Tibialis posterior

- Flexor hallucis longus

Many of the superficial muscles also have a deeper portion which is located behind the superficial part.

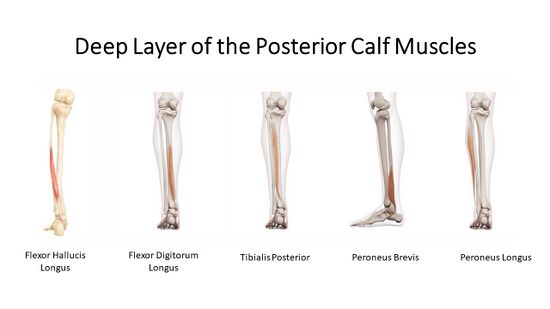

The deep muscles of the posterior calf (Figure 6):[5]

- Semimembranosus tendon

- Tendon of biceps femoris

- Popliteus

- Tibialis posterior

- Flexor hallucis longus

- Flexor digitorum longus

- Peroneus brevis

- Peroneus longus

The deep muscles are continuous. While they go into the foot, they bypass the heel and attach more distally.

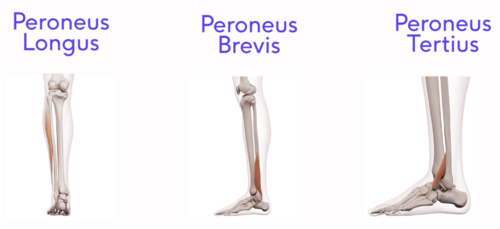

Dysfunction in the plantarflexion muscles can also have an impact on the antagonist muscles, creating an imbalance in functioning. Hence, even though it may not be indicated in the initial treatment of PHPS, the eventual assessment and treatment of these antagonist muscles are necessary to enhance the optimal resolution of PHPS.[5] These muscles include the lateral muscles of the lower leg consisting of (Figure 7):

Figure 7. Lateral Calf Muscles

Treatment of these muscles can be performed with the patient in supine or in side-lying with a pillow between the legs. The fascia covering these muscles is often very stiff as well, and this might necessitate increased pressure to reach the muscle tissue.

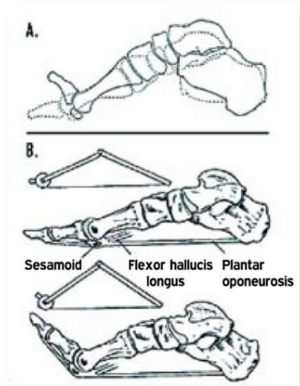

When assessing the posterior calf, it is important to consider the findings of the Windlass Test. As previously discussed, the Windlass test:

- Only identifies around 30% of individuals with PHPS [12], and is

- Unable to support stress on the plantar fascia as a cause of PHPS

However, the symptoms experienced by some individuals with PHPS during the Windlass test might be explained by stress on the calf muscles, specifically the flexor hallucis longus muscle (Figure 8). Patients are not all affected in all of the posterior calf muscles which provides a possible theoretical explanation for why the Windlass test is not positive in all patients complaining of PHPS.

Exercises for Plantar Heel Pain[edit | edit source]

Exercise is an important aspect of managing any musculoskeletal injury, but it requires the cooperation and involvement of the patient. From the research and discussions about PHPS, we know that:[5]

- Stretching exercises are an effective treatment for PHPS, but not a stand-alone treatment[9][13][14]

- Many patients with PHPS are sedentary and would benefit from moving more[15][16]

- Deep massage to the calf muscles has a positive effect on heel pain which implies dysfunction of the muscle[3]

- Massage restores the ability of the muscle to contract (broaden/widen)[17]

- Stretching exercises have the capacity to restore the length of the muscle

- Strength and proprioception training need to also be included in order to restore the full function of the muscle

When prescribing exercises for PHPS, it is necessary to consider:

- The muscles crossing the knee, as well as the ankle. Thus, a long stretch of the calf, such as the commonly used lunge stretch is useful (Figure 9)

- The muscles which only cross the ankle. These muscles require exercises with a bent knee

- Including a variety of exercises in order to stretch the posterior calf muscles in various ways

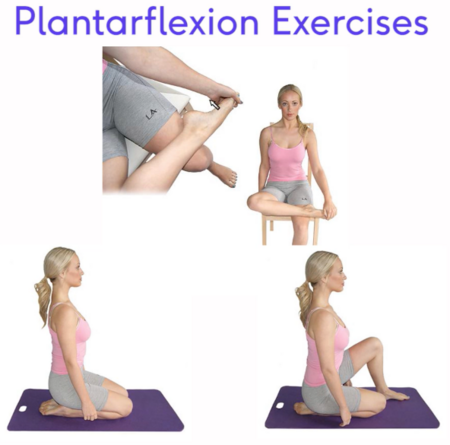

Exercises should include dorsiflexion stretches in order to lengthen the posterior calf muscles (Figure 10) as well as plantarflexion stretches (Figure 11) in order to lengthen the antagonists and restore full function to these muscles.[5]

Figure 10. Dorsiflexion Stretch Exercises [5]

Figure 11. Plantarflexion Stretch Exercises [5]

In order to restore full function to the foot, all aspects of muscle function should be considered. It is, therefore, also necessary to consider and incorporate:[5]

- Mobility of the toes (Figure 12)

- Lengthening of the short muscles of the foot (Figure 13)

- Various rehabilitation exercises in order to restore athletes to their full function (Figure 14)

- Proprioception, as pain and inactivity negatively impacts the proprioception of the foot (Figure 14)

Figure 12. Toe mobility exercises [5]

Figure 13. Stretch of plantar flexors and short muscles of the foot [5]

Figure 14. Rehabilitation and Proprioception exercises [5]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Mischke JJ, Jayaseelan DJ, Sault JD, Emerson Kavchak AJ. The symptomatic and functional effects of manual physical therapy on plantar heel pain: a systematic review. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. 2017 Jan 1;25(1):3-10.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Pollack Y, Shashua A, Kalichman L. Manual therapy for plantar heel pain. The Foot. 2018 Mar 1;34:11-6.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Saban B, Deutscher D, Ziv T. Deep massage to posterior calf muscles in combination with neural mobilization exercises as a treatment for heel pain: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Manual therapy. 2014 Apr 1;19(2):102-8.

- ↑ Cyriax J. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine - Volume 1. 8th Edition. London: Bailliere Tendal; 1982.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 5.22 5.23 Bernice Saban. The Theory and Practice of Massage and Exercise for Plantar Heel Pain. Plus Course. 2021

- ↑ Gardner T, Kenter K, Li Y. Fibrosis following acute skeletal muscle Injury: mitigation and reversal potential in the clinic. Journal of Sports Medicine. 2020 Sep 1;2020.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Chaves P, Simões D, Paço M, Pinho F, Duarte JA, Ribeiro F. Pressure Applied during Deep Friction Massage: Characterization and Relationship with Time of Onset of Analgesia. Applied Sciences. 2020 Jan;10(8):2705.

- ↑ Farooq N, Aslam S, Bashir N, Awan WA, Shah M, Irshad A. Effectiveness of transverse friction massage of Flexor digitorum brevis and Calf muscle stretching in Plantar fasciitis on foot function index scale: A randomized control trial. Isra Med J. 2019;11(4):305-9.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Katzap Y, Haidukov M, Berland OM, Itzhak RB, Kalichman L. Additive effect of therapeutic ultrasound in the treatment of plantar fasciitis: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2018 Nov;48(11):847-55.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Chaves P, Simoes D, Paco M, Pinho F, Duarte JA, Ribeiro F. Cyriax's deep friction massage application parameters: Evidence from a cross-sectional study with physiotherapists. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice. 2017 Dec 1;32:92-7.

- ↑ Stasinopoulos D, Johnson MI. Cyriax physiotherapy for tennis elbow/lateral epicondylitis. British journal of sports medicine. 2004 Dec 1;38(6):675-7.

- ↑ De Garceau D, Dean D, Requejo SM, Thordarson DB. The association between diagnosis of plantar fasciitis and Windlass test results. Foot & ankle international. 2003 Mar;24(3):251-5.

- ↑ Sweeting D, Parish B, Hooper L, Chester R. The effectiveness of manual stretching in the treatment of plantar heel pain: a systematic review. Journal of foot and ankle research. 2011 Dec;4(1):1-3.

- ↑ Burton I, McCormack A. The effectiveness of combined extracorporeal shockwave therapy and exercise for plantar heel pain: A systematic review. Exploratory Research and Hypothesis in Medicine. 2022 Mar 25;7(1):39-52.

- ↑ Thomas MJ, Whittle R, Menz HB, Rathod-Mistry T, Marshall M, Roddy E. Plantar heel pain in middle-aged and older adults: population prevalence, associations with health status and lifestyle factors, and frequency of healthcare use. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2019 Dec;20(1):1-8. DOI:10.1186/s12891-019-2718-6

- ↑ Riel H, Cotchett M, Delahunt E, Rathleff MS, Vicenzino B, Weir A, Landorf KB. Is ‘plantar heel pain’ a more appropriate term than ‘plantar fasciitis’? Time to move on. Br J Sports Med. 2017; 15(22):1576-1577.

- ↑ Chamberlain GJ. Cyriax's friction massage: a review. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 1982 Jul 1;4(1):16-22.