The Role of the Physiotherapist in Palliative Care for People With Lymphoedema

Introduction[edit | edit source]

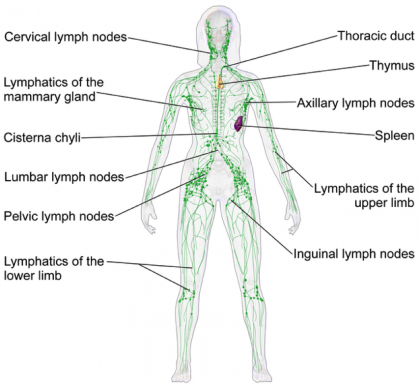

Lymphoedema described swelling that can occur in the arms and legs and is caused by blockages in the lymphatic system. The lymphatic system is part of the body's immune system that plays a role in fighting harmful cells, for example, bacteria. It consists of lymph fluid, lymph nodes, lymph vessels and lymph tissue. There are several causes of blockages of the lymphatic system:

- Infections i.e. parasitic, such as filariasis, or skin infections, such as cellulitis

- Injury or trauma

- Tumours

- Cancer treatments such as radiation therapy

- Skin infections, such as cellulitis (more common in obese people)

- Surgery

Lymph tissue insulates and protects the lymphatic system from damaging cells. Lymph fluid is protein rich and contains infection-fighting white blood cells. It circulates throughout the lymphatic system and is formed when interstitial fluid is collected through lymph channels (vessels, ducts and capillaries). Lymph is primarily made up of a white watery substance and flows unidirectionally towards the heart to provide cells with oxygen. The main functions of the lymphatic are listed below:

1. Helps immune system respond to the body

2. Redistribution of fluid in the body

3. Lymph carries proteins, solids, and liquids away from tissue space

a. Remove waste products from interstitial space (between all body tissue) [1]

b. Bacteria, toxins and foreign bodies are removed from tissues

4. Controls the flow of large molecules around the body[2]

5. Controls tissue fluid homeostasis to maintain the structure and functional aspects of tissue[3].

Lymph nodes tend to be found in clusters ingrained within adipose tissue (contains fat cells). Their shape and size varies depending on gender and where the nodes are located in the body[4]. There are approximately 600 to 700 lymph nodes located around the body, specifically under the arm, in the abdomen, groin and neck[5]. Their role involves receiving lymph fluid via afferent vessels and transporting it around the body using specific lymph channels located on left and right sides. The fluid then passes through superficial primary lymph vessels (that drain the skin) and is emptied into deep secondary lymph vessels (which also contains drainage from internal organs). Adequate flow of lymph fluid is dependant on muscle contractions and an efficient respiratory system, for example, exercise[6].

Examples of lymph nodes located in the upper body include: axillary; lateral; subscapular; pectoral; upper and lower; central; infraclavicular; subpectoral and interpectoral nodes. Some of the lymph nodes located in the lower extremities include: inguinal; superficial inguinal and the intercalated nodes. As stated above, there are a number of lymph nodes located in the abdomen and pelvic areas, for example, iliac; lumbar; gastric; pancreaticosplenic; mesenteric; hepatic and rectal lymph nodes.

Lymphoedema occurs when the lymphatic system becomes blocked from localised fluid retention and tissue swelling within the body. This happens when the function of the lymphatic system is compromised in some way. Lymph pathways are unable to exchange nutrients effectively within the interstitial spaces, causing a build up of excess fluid. Upper and lower extremities are affected depending on which area of the body is damaged. The cause of onset determines whether the affected person has either primary or secondary lymphoedema. There is no cure for lymphoedema and many patients will need life long treatment to control the swelling and pain. This chronic condition can impact on both physical and emotional well-being. As there is no cure for lymphoedema the treatment is often termed as palliative care[7].

Palliative Care[edit | edit source]

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines palliative care as an "approach that improves the quality of life of patients (adults and children) and their families who are facing problems associated with life-threatening illness. It prevents and relieves suffering through the early identification, correct assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial or spiritual" [8].

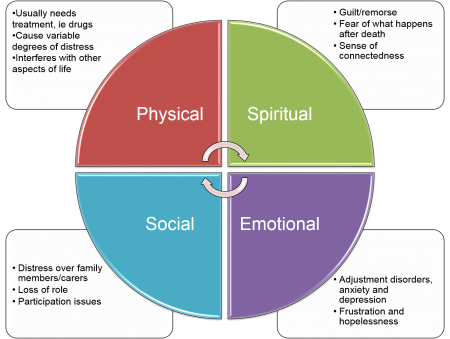

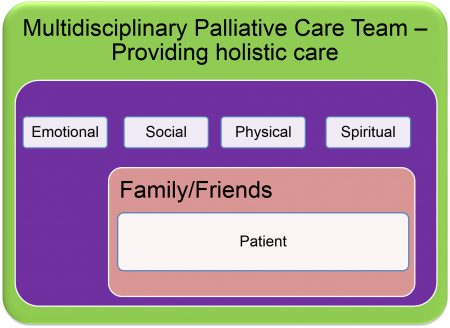

As the primary aim of palliative care is to help alleviate pain and suffering, it is important to understand that pain is multidimensional - consisting of physical, emotional, spiritual and social components. Cicely Saunders (the founder of palliative care) referred to this as “total pain”. This concept of pain allows us to have a wider, more holistic approach to care for patients.

The image here outlines the components of pain and how they affect the patient.

Aims of palliative care[9]:

- To maintain quality of life until death

- Provide relief from pain or other symptoms which may cause distress

- Help patients to live as actively as possible

- Help family members to cope during a patient’s illness and during their own bereavement

- Integrate spiritual and psychological aspects into a patient’s care

- Be applied early and in conjunction with other therapies

Background[edit | edit source]

Hospices in the UK and Ireland have been around since the 1900s, however, they were few in number and run by religious foundations to provide care to the poor. The patients in these hospices received excellent nursing and spiritual care but medical input was minimal as it was believed then that the doctor’s role was to cure.

During the 1950s, there was considerable professional and public interest in cancer but the main focus was on curative treatment. Patients who were considered terminal and were dying from cancer were overlooked and were told to go home, as there was nothing that could be done or were scattered in various hospital wards, abandoned by doctors. In the post-war years, a shift began to emerge in the published work with new studies showing both the clinical and social aspects of care for patients who were dying from cancer. This work in oncology helped to shape the worldwide development of palliative care[10].

Cicely Saunders may be recognized as the founder of the palliative care movement around the 1970’s. Having trained as a nurse and then a social worker, in 1959, Saunders qualified in medicine and began working in St. Thomas’s Hospital in London[11]. In 1960, Saunders focused her attention on patients who were in the final stages of cancer, especially those patients with complex problems from the point of view of pain and general distress. Her research and writings were built on the individual experiences of her patients and by 1967 she had collected data for 1100 cases, where she described the physical and mental suffering of each patient[10]. Saunders inspired the concept of total pain which includes physical, emotional, social, mental and spiritual components and believed in constant pain management to relieve suffering. In 1967, Cicely Saunders opened St. Christopher’s Hospice in London which was the world’s first modern hospice. Here, she brought together large numbers of patients with terminal illness and staff to take care of them[11]. The hospice quickly became an inspiration and established itself as a centre of excellence, giving equal importance to clinical care, education and research. Research was conducted surrounding the topics of pain control and administation of strong opiates to relieve pain. These clinical and organisational studies went on to play a major role in the advancement on palliative care[10].

The success of St. Christopher’s Hospice soon became a catalyst for the development of hospices in the UK. During the 1980s, about 10 new hospices were opened a year, some were funded by the NHS and others were privately or charity funded. There was also a development among hospitals and in 1976 a terminal care team was established in St. Thomas’s Hospital, London. Between 1982 and 1996 the number of hospitals with a multidisciplinary palliative care team or a specialist nurse increased dramatically from 5 to a staggering 275.

During this time, two well-known UK charities also assisted in influencing change. The first of these charities was the MacMillan organisation which was founded in 1911[12]. During the 1970s the organisation went through a period of phenomenal expansion. The organisation became more involved in palliative care and supporting specialist professional posts, academic positions and service development. The second charity is the Marie Curie Memorial Foundation, established in 1948[13]. This foundation was involved in creating a domiciliary nursing service for patients with cancer. It created nursing homes and ran a laboratory-based research programme. During the 1980s when new hospices were opening across the UK, the Marie Curie nursing homes evolved into specialist palliative care centres and the charity supported more research and educational activities in palliative care[10]. By the 1990s there were over 1000 specialist Macmillan nurses and 5000 Marie Curie nurses working across the UK in palliative care. By 1987, palliative medicine was established as a subspecialty of general medicine and in 1995 the specialty of palliative care was formally approved[10].

Service Delivery[edit | edit source]

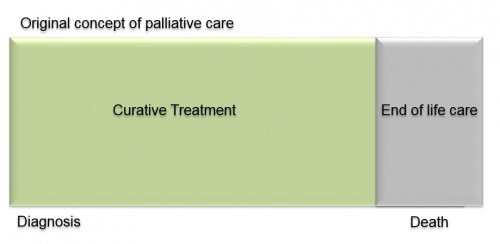

Since the inception of the modern hospice and palliative care movement led by Cicely Saunders, palliative care has continued to evolve, has developed into a medical specialty and is now integrated into mainstream medicine in many countries. Historically there was an emphasis on curative treatment with end of life care only being implemented when treatment had failed and there was nothing more to be done. The image below depicts this -

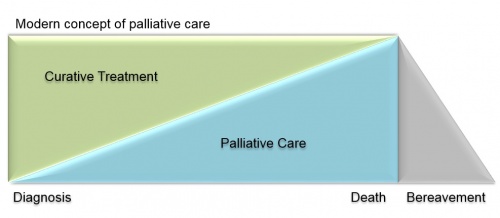

However, as healthcare has evolved a newer concept has emerged, it is now replacing the dated older model. Palliative care should improve the quality of life of people suffering with life-threatening conditions, therefore, a realistic dialogue between patients, family and professionals should be introduced earlier in the disease trajectory[14]

This is illustrated in the image below which shows the new concept of care. Active treatment and palliative care should be a seamless process through a disease trajectory from the point of diagnosis or at any point along the trajectory[14].

However, this does not always happen, due to differences between countries and societies. There is a strong bias towards a curative approach in modern medicine, especially in high-income countries where curative treatments may have priority ahead of palliative care. Due to the aging population in developed countries, the burden of disease on healthcare will continue to increase, challenging the knowledge and skills of professionals. With the advances in treatments for cancer and other conditions, patients are living with more co-morbidities and palliative care services must be prepared to provide care over longer periods of time throughout the disease trajectory.

Where Care is Provided?[edit | edit source]

Hospices are probably the most well known setting for palliative care, however palliative care takes place in multiple settings that people often do not think of. Hospices can be a ward or unit within a hospital or can be a stand-alone service. Hospices in the UK are generally stand-alone services with the aim of alleviating disease or therapy-related discomfort and stabilising the status of patient by offering psychological and social support. Cicely Saunders once said that hospices should be a welcoming environment and have a sense cheerfulness and peace.

This diagram represents the locations where palliative care can be delivered - each of which will be discussed in further detail below.

Hospital palliative support teams – Provide advice to patients, their family, carers and other clinical staff. The team provide education and liaise with other services both in and out of hospital. An aim of the team is to alleviate multiple symptoms patients may have - this may be done by prescribing directly or will provide advise regarding symptom management.

Home care teams – Provide specialist direct care to patients in their home where they also support their families and carers. The team may provide specialist advice to GPs, nurses or other clinicians involved in the patient’s case. There is good evidence to show the benefits of home specialist palliative care compared with usual care.

Outpatient services – This service is available for patients who live at home but are still able to attend clinics. These services may be offered from a hospital or inpatient palliative care unit. This service can help to introduce patients to the palliative care process earlier where advanced care planning can be put in place. Unfortunately there is little to no evidence on the effect of these services.

Day care centres – These are spaces in hospitals, hospices or the community which are specially designed to provide additional support to patients and their families. Usually patients who attend a day centre are already in the care of a home palliative care team. The nature of the service offered may vary depending on the patient’s needs, from medical/health orientated to more recreational or social services where complementary therapies may also be offered.

Who Provides Care?[edit | edit source]

In order to achieve the aims of palliative care which are to affirm life and help support patients to live as actively as possible until death, all four components (emotional, social, physical and spiritual) of care should be covered. This is achieved by the collaboration of professionals using a multi- and interdisciplinary team (MDT and IDT) approach. The professionals involved in the MDT is likely to include specialist palliative nurses or physicians. However, depending on the service and needs of the indiviual other professionals may be involved such as social workers, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, psychologists, pharmacists and religious officials.

Each member of the MDT should have the necessary knowledge and practical skills of assessing and managing patient’s symptoms, be able to identify changes in the patient’s condition and be involved in the patient’s management plan. Care is offered based on the patients needs, therefore effective team work and co-ordination of support is essential. Care is focused on controlling pain and other symptoms, this is based on the needs of the patient at that time (this correlates to what was discussed in the TEDx video earlier), not on the disease prognosis, hence professionals must be flexible and able to adapt to these changing needs[15].

This image below shows how the MDT collaborates with the patient and their family. The patient is always at the centre of care, closely connected to their family and friends with the 4 components of care included.

Figure 5[16]

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

Palliative and specialised palliative care services offer a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach which was discussed earlier. Key principles must be applied to the assessment such as considering the patient as a whole person, focusing on quality of life rather than quantity. Management should be decided by the patient and there should be good communication for effective assessment and management[17]. The assessment should involve a patient-centred approach in order to elicit the physical, social and psychological needs of the patient[18].

The palliative lymphoedema assessment aims to:

- Understand the patient’s main concerns, goals and priorities

- Help the clinician understand the main cause of and the mechanisms behind the swelling

- Understand the underlying condition and how quickly it is progressing

Oedema is a direct result of multiple factors relating to a terminal illness. It can be distressing for patients and a management challenge for health professionals. It is estimated that 5-10% of new referrals to palliative care have oedema but this is also thought to be underestimated[17]. Heavy and swollen limbs can cause proximal pain while patients with active malignancy may experience neuropathic pain due to nerve compression. Up to 67% of patients experience pain as a result of oedema. For patients, lymphoedema may be seen as a constant reminder of their cancer or illness. The swollen limb is heavy and uncomfortable which leads to a reduction in mobility and function[19]. All of which emphasie the importance of a detailed assessment to identify problems and effective management that focusses reducing the patients pain and other associated symptoms.

Assessment[edit | edit source]

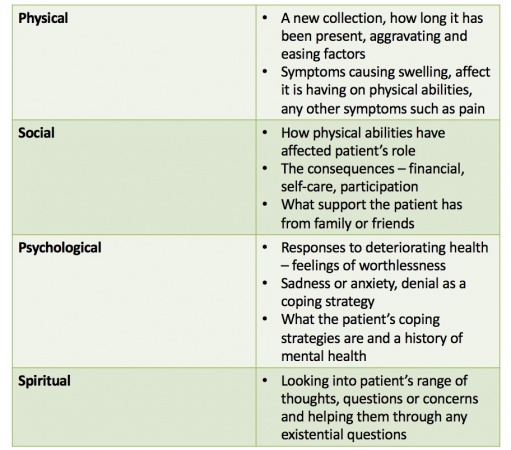

The assessment should include physical, social, psychological and special aspects along with a history of the illness and medication to further explore the underlying causes[17]. An examination is then carried out and baseline measurements are taken. This helps to plan the programme of care, assess the response to treatment, identify risks of potential complications and may show signs that confirm the cause of the oedema. Due to the nature of the disease patients priorities often change, therefore the assessment is ongoing and reviews of priorites and goals occur regularly[19]. From the assessment, the priority will be to negotiate a care plan based on the patient’s problems and the best approach to alleviate these issues[18]. The assessment includes a full history of the oedema including the following areas[17]:

Holistic Needs Assessment[edit | edit source]

In 2010 the National Cancer Survivorship Initiative[20] identified some key areas to deliver high-quality care for people with cancer in the UK. One of the identified issues was to develop a holistic assessment and personalised care planning. This was a shift away from the traditional thought of ‘one-size-fits-all’ when care planning. From here, the Holistic Needs Assessment (HNA) was developed.

A Holistic Needs Assessment (HNA) is an assessment tool specifically developed for cancer patients and should be used during every cancer patient’s care. It can make a large impact on a patient’s overall care experience and greatly improves outcomes through recognising and resolving any problems quickly[21].

The assessment is a process of collecting and discussing information with the patient to develop a clear understanding of the patient's individual needs and current self-management strategies. This holistic assessment is patient-centred as it focuses on physical, emotional, spiritual, mental, social and environmental factors. From here, an individual care plan is created specifically tailored to their needs [20].

It has been shown that having a HNA when patients are nearing the end of treatment helps to identify areas to be discussed with a healthcare professional. The information from this discussion will then be used to develop a care plan with the patient. The care plan is there to support the patient during and after their treatment and should include[21];

- Addressing any physical or everyday concerns

- Direction to local or national support groups

- Information about local Health and Wellbeing Clinics, educational events or self management courses available

- Referral to appropriate healthcare professionals for support

- Lifestyle advise/changes

- Information or referral to an appropriate physical activity programme

- Information or referral for advice on diet and nutrition

- Referral for psychological support

- Support related to work and finance concerns

- Support for spiritual needs

Supporting Evidence[edit | edit source]

It was determined in 2009 that a surprisingly low less than 25% of people with cancer were offered a holistic needs assessment or care plan[21]. Although many institutions and professionals are beginning to implement an assessment approach, there is still a long way to go before this is a national standard way of practice.

The Holistic Needs Assessment and Care Planning document from Macmillan concludes that while there is an abundance of evidence focusing on the needs of patients with cancer and the multiple assessment tools used, there is little evidence for the appraisal of the HNA[22]. More research that looks into the experiences of people with cancer who have undergone the HNA process is needed to determine its value in clinical practice.

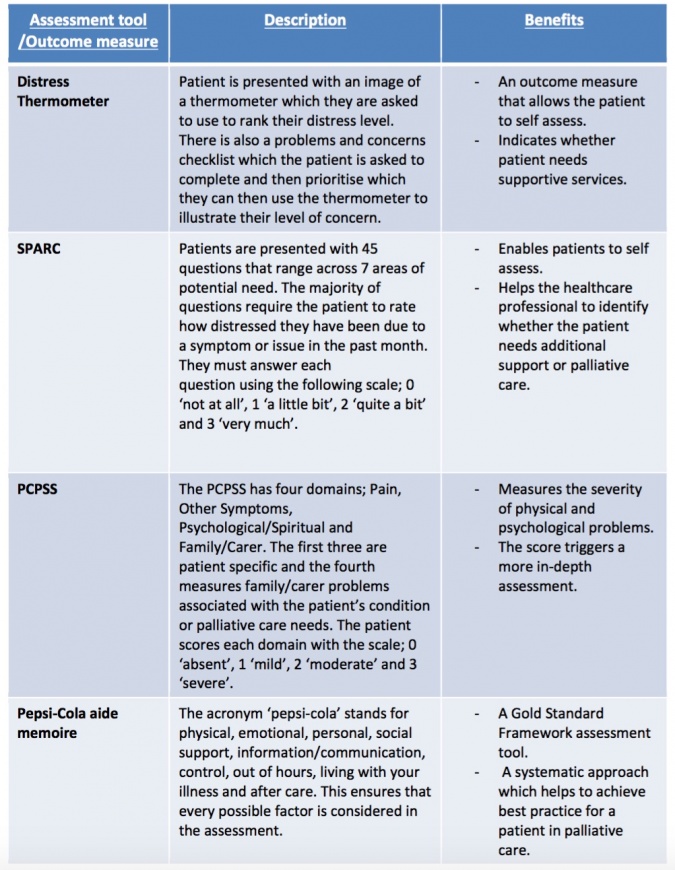

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

An outcome measure is a tool used to measure the quality of delivery of patient care and indicator of whether an intervention has had any positive effect or not[23].

The use of an outcome measure as a tool can be very valuable during an assessment. The main benefits are[20]:

- Ensures the focus is on the patients specific needs

- When used effectively, it provides a structured assessment conversation allowing the patient’s worries to be prioritised

- Ensures all areas of assessment are covered

- Patients become familiar with the tool and it can be used by different healthcare professionals involved in their care

There are a range of outcome measures and assessment tools available to physiotherapists. The most commonly used tools within a palliative setting include[20]:

• Distress Thermometer

• Sheffield Profile for Assessment and Referral for Care (SPARC)

• Palliative Care Problem Severity Score (PCPSS)

• The Pepsi-Cola aide-memoire

Treatment challenges [edit | edit source]

The main aim of palliative rehabilitation is to set treatment goals that allow a patient to maintain or improve functions and delay disease progression for as long as possible. Losing functional ability can cause a patient to view themselves differently and reduces their independence, consequently this can impact their psychological well-being. Therefore, physiotherapists have an important role in helping patients maintain their independence and achieve other goals they may have[24]. Goals need to be short-term and adaptable due to the ever changing nature of a palliative condition. Sometimes it is necessary to carry out a new assessment each time you see a patient due to this varying nature[24].

With regards to lymphoedema patients, physiotherapists usually work towards the goal of restoring ‘near normal’ limb shape and size. However, in a palliative setting this goal is often unrealistic, therefore, goal setting must be sensible and specific to the patient's individual needs. Goal setting with the patient should include close interaction with the physiotherapist and other health professionals involved in their care to ensure they are adequately educated in a range of self-management strategies. Acceptable palliative goals include, slowing down the progression of swelling and reducing other symptoms associated with lymphoedema [17].

Patients may have dramatically reduced physical capacity. If their illness has compromised neurologic structures, they may be plegic or paretic, and therefore unable to self- bandage or perform remedial exercises. Further, they may be significantly limited by symptoms such as fatigue and dyspnoea due to marked deconditioning. The coordination, dexterity and strength requirements for bandaging and donning compression garments can elude even healthy patients; therefore, these potential difficulties should be considered when formulating a management plan for terminally ill patients [17].

Physiotherapy Interventions[edit | edit source]

The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (CSP) produced a document outlining the background and treatment of lymphoedema[25]. This document states that patients will undergo 3-4 weeks of intensive therapy, followed by lifelong monitoring, which includes self-management and 6 month reviews. The need for early access to specialist physiotherapy intervention in order to prevent serious complications is also highlighted.

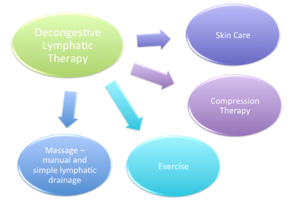

Decongestive lymphatic therapy (DLT) as discussed by the CSP is viewed as the gold standard of care for lymphoedema[26].This treatment approach is effective and significantly reduces the percentage excess limb volume as well as improving quality of life[27] .

Decongestive lymphatic therapy encompasses four main components[28];

The treatment of lymphoedema should be specifically tailored based on the site, severity and complexity as well as their psychosocial status[28]. The success of treatment does not solely rest on the therapist; patients and carers must play an active role from an early stage.

Alongside the physical difficulties that people with lymphoedema face - emotional and social implications may also arise. Evidence has suggested that through specific management and targeting of the physical symptoms, these psychosocial issues can be reduced to enhance the individual’s quality of life[27].

The management of lymphoedema is split into intensive and maintenance stages, both of which have very different approaches. The goals during the intensive stage of therapy are to reduce and control the swelling, maintain skin quality and educate the patient in order for them to reach a stage where they are ready to progress into the maintenance phase of treatment[29]. This is achieved through a number of approaches aiming to reduce the load, decongest the lymphatic system, encourage system function and stimulate drainage through various routes[28].

Once swelling is bought under control patients will progress to the maintenance stage. During this stage people with lymphoedema are educated to self manage their condition and will be reviewed less frequently by a specialist.

Decongestive Lymphatic Therapy (DLT)[edit | edit source]

Traditionally lymphoedema is managed with DLT and is based on four pillars of care: compression, massage, skin care and exercise[28]. However, routine intensive management using decongestive lymphatic therapy may not be appropriate due to weakness and frailty so this must be modified and adapted[18]. Please refer to the previous section about treatment and management of lymphoedema if you need to refresh your memory of the four components of DLT.

In a palliative setting, physiotherapists need to approach lymphoedema management with an understanding that disease processes are dynamic and may progress rapidly. In order to offer patients long-term relief, the chosen treatment plan must also have the ability to adapt quickly therefore treatment must be feasible and flexible. Therefore, DLT is modified to suit the needs of a palliative patient. Modified DLT has the capacity to significantly benefit patients with far advanced disease who have lymphoedema or multi-factorial oedema. DLT can enhance patients’ function and comfort while preventing needless complications and enhancing psychological well-being [17].

Compression Therapy[edit | edit source]

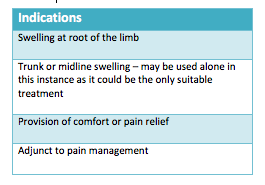

Patients with mild swelling can be managed in compression garments either ready made or made to measure[28]. Poorly fitted garments can damage the skin and push fluid to areas that have no compression applied, e.g. fingers. Palliative bandaging consists of layers of padding and short-stretch bandaging over a cotton liner and will include bandaging the digits[18]. In palliative patients there is a risk of forcing fluid into adjacent areas, e.g. the genital or breast area. Expertise is required to judge the correct amount of pressure to apply to support the swollen limb but prevent truncal swelling[18]. Therefore any bandaging should be carried out or supervised by a lymphoedema practitioner.

Compression therapy consists of two main methods – multilayer lymphoedema bandaging (MLLB) and compression garments. Overall, compression therapy increases lymphatic drainage, reduces capillary filtration, promotes fluid movement to less compressed areas of the body and improves the action of the venous pump[30]. Furthermore, bandaging aims to improve the shape of the limb, soften fibrosclerotic tissue, support and improve skin condition[31].

Once no further benefit is being obtained from compression bandaging during the intensive phase, patients should be managed by compression garments for long-term maintenance[32]. MLLB may also be used as part of long-term management if compression garments are not suitable [31].

The combined treatment of bandaging followed by compression hosiery has been found to yield better results for reduction of moderate to severe lymphoedema, which was maintained for at least 6 months, compared with hosiery alone [33]. These results came from a relatively large randomised controlled parallel-group trial. Hence the International Consensus recommends this as the optimal course of treatment for people with lymphoedema.

Compression Bandaging[edit | edit source]

Compression bandaging is considered if the patient presents with any of the following factors[28]:

- Fragile, damaged or ulcerated skin

- Distorted limb shape

- Limb too large for compression garments

- Areas of tissue thickening

- Lymphorrhoea

- Lymphangiectasia

- Pronounced skin folds

There are a number of contraindications stated below[28]:

- Severe arterial insufficiency

- Uncontrolled heart failure

- Severe peripheral neuropathy

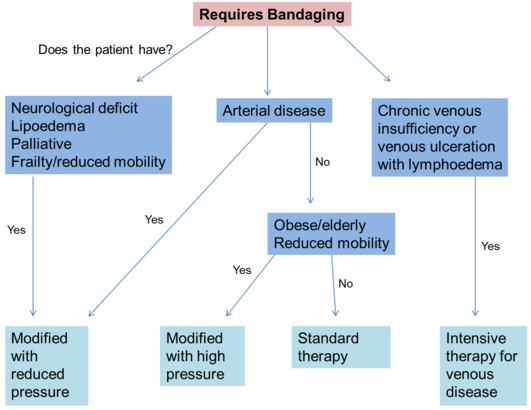

Once indications and contraindications have been considered, the health professional is required to make a decision regarding the course of treatment. Based on the patient's presenting symptoms, condition and medical history, they may require slightly modified treatment. The following flow chart visualises the decision making process that occurs at this stage:

The bandages used for MLLB are inelastic which result in high and low pressures exerted during movement and rest respectively[31]. Elastic bandages produce less variation of pressure; these may be indicated if patients are immobile, have venous ulceration, lymphatic or venous disease or if the expected time of application is longer than normal[28].

As with most treatments, MLLB can be adapted to suit the patient needs by either adjusting pressure, frequency of reapplication, bulk of bandage and type of bandage[28]. If pressure is not applied correctly venous and lymphatic flow can be compromised, therefore the proximal movement of fluid is reduced and swelling may present in the extremities[31]. When applied to the lower limb, care must be taken to ensure that the patient is still able to wear shoes during treatment as normal gait pattern is encouraged to maintain an effective calf and foot muscle pump[31].

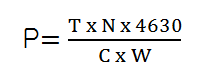

Pressure applied is calculated using Lapase's Law:

P = pressure under the bandage (in mmHg),

T = bandage tension (Kgf)

N = number of layers

C = limb circumference (cm)

W = bandage width (cm)

The basic principles of MLLB have been discussed. The following two videos show the application of MLLB to upper and lower limb lymphoedema. By watching these, you should gain a clearer idea of the appearance of MLLB and how it is applied by a specialist physiotherapist or other health care professional.

MLLB has been discussed, however more recently, a new bandaging system known as Coban 2 has been developed which can be used an alternative to MLLB. MLLB consists of a thick padding layer covered by multiple compression bandage layers, however Coban 2 differs and only consists of a comfort layer and a compression layer that cohesively bond together[34]. Coban 2 bandaging eliminates the need for multiple thick layers, resulting is a much less bulky appearance and allowing the patient more mobility and freedom.

Lamprou and colleagues[34] conducted a prospective randomised controlled trial comparing Coban 2 with traditional bandaging methods in the treatment of lower limb lymphoedema. The results of this study found Coban 2 to be equally as effective in reducing limb volume.

Franks and colleagues[35] studied the use of Coban 2 in arm and leg lymphoedema. Again this study supported the use of Coban 2 in the effective management of lymphoedema with the lower limb showing a greater reduction in swelling.

Although both of the above studies had relatively small sample sizes (40 and 24 participants respectively) resulting in low statistical power, they both showed encouraging results for the use of the new bandaging system.

A multicentre randomised controlled trial with 82 participants investigating the frequency of application of Coban 2[36]. Results found constant therapeutic effect was maintained when bandages were reapplied every four days. Compared with MLLB, which requires reapplication daily at certain stages of treatment, the Coban 2 bandages allow patients to have more freedom and independence. This next video shows the application of Coban 2 bandaging and explains some more information about this new system.

Compression Garments/Hosiery[edit | edit source]

Compression garments will be considered when a patient is reaching the end of the intensive phase of treatment once regular limb shape has been restored and the patient’s skin is fully intact and robust enough to tolerate the use of garments[37][38]. Garments require precise measurement as they are hand-made to measure specifically for the individual patient.

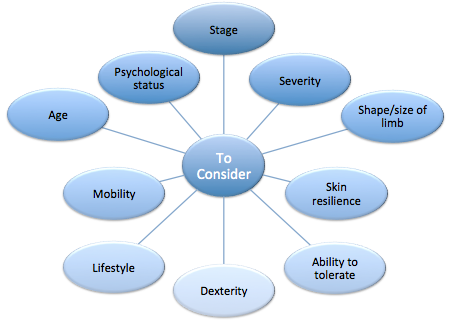

Although garments are important in the management of lymphoedema, patient and clinician must come to an informed decision regarding the appropriateness of this treatment modality.

Doherty et al.[37] explains a number of factors that should be considered when assessing for compression garments (see image below). Once these have been considered and the patient is deemed appropriate for compression garments, meaurements will be taken by a qualified health professional, which may be a physiotherapist.

Once the progression from bandages to garments has been made, swelling and other symptoms must be monitored. If swelling is not controlled within the first three months of wearing compression garments, clinician and patient should consider further intensive therapy using MLLB in order to bring the swelling under control[31].

Garments are either constructed as a flat knit or a round knit. Flat knit are knitted as a flat garment then joined at the seams, these are generally thicker and firmer. Round knitted garments are viewed as more aesthetically pleasing, as they are thinner than flat knit and are continuously knitted cylindrically without any seams[28].

Once measurement and construction of the garment is completed, the health professional will assess the garment for fit and check that the patient or carer is able to apply and remove the garment correctly. Advice regarding the care at home will be provided in person and leaflets may also be given to the patient[28]. If garments are poorly fitted, the swelling may not be contained and damage can occur to the tissues. This could result in discomfort and reduced tolerance leading to patients being unwilling to use compression hosiery as a long-term management option[37]. As well as limb compression garments, if patients have trunk or breast lymphoedema garments or specialised bras can be provided[28].

Skin Care[edit | edit source]

In palliative patients, the skin can become very fragile and the aim is to prevent any damage. As a consequence of swelling, large skin folds can appear where infections may develop [28]. Infections can also arise if the skin becomes damaged or broken, therefore adequate skin care to maintain the integrity and manage any problems that occur is fundamental in the care of people with lymphoedema[28][39]. At both intensive and maintenance stages, it is important to emphasise the need for a skin care regime to maintain the skin integrity.

Care should be taken to wash and dry thoroughly, especially between the digits and any skin folds. Apply an unscented moisturiser to prevent drying of the skin. If compression hosiery is being applied care should be taken to prevent damage during application. Any breaks in the skin can result in lymphorrhoea – lymph fluid leaking onto the surface of the skin. The extent of the lymphorrhoea will depend on the size of the tear in the skin and whether the limb is dependent or not. The fluid causes maceration of the skin, soaking of clothing, footwear and bedding and can be very cold and distressing for the patient.

Mild lymphorrhoea can be treated with an absorbent dressing and continuing with compression hosiery. In some cases, however, the management is purely palliative as bandaging may not stop the lymphorrhoea, especially if the patient is sitting in a chair for the majority of the time. Bed rest is occasionally the only cure for lymphorrhoea and this inevitably takes place as the patient gets closer to death[18].

The main principles of skin care are:[32][40]

During the assessment, health professionals must inspect the skin condition using palpation and observation to check for any changes or damage[40]. If changes have occurred these must be monitored and managed correctly. Following assessment, the skin will be cleansed and emollients applied.

Washing removes dirt and bacteria from the skin, this is essential to prevent infection; however washing can remove the protective lipid layer that prevents water loss and protects the skin from infection. Therefore emollients are applied to re-establish this layer, thus preventing any further water loss and maintaining the protective barrier[32]. Following cleansing of the skin, it is highly important to ensure the skin, in particular, the skin folds are dried properly. If not, these areas will provide the perfect environment for infections and bacteria to develop.

Abrasive or scented soaps should be avoided and natural or pH neutral soaps are recommended[28][40]. This is because normal soaps contain detergents, are often scented and include preservatives, which can all irritate or dry the skin.

As shown in the videos in the above section (Compression Therapy) emollients are applied prior to bandaging. These are available in various forms including, moisturisers, soaps substitutes or bath oils. Moisturisers area also available in different forms including creams, lotions and ointments[40]. The Lymphoedema Framework[28] recommends the use of ointments, which contain little or no water; this hydrates the skin better than creams and lotions.

The body’s natural response to sunburn is to increase blood flow to the affected area. For people with lymphoedema this will increase the load on an already impaired lymphatic system and may increase swelling. Therefore it is advised that people with lymphoedema take extra care to avoid sunburn[40].

Despite the treatment offered infections may still occur that must be managed by thorough close monitoring, skin hygiene, ensuring skin is dried following washing and an anti-fungal powder or cream applied until the infection disappears[40].

Although skin care is an integral part of lymphoedema management, some patients experience barriers that prevent adequate skin care and result in infections. James[41] studied the perceived barriers to skin care, which included physical limitations, expense, poor understanding, anxiety and motivational issues. This indicates that health professionals play a large role in educating patients about the importance of skin care to facilitate self-management. Health professionals should be aware of these potential barriers and be able to overcome them through education and support.

Exercise[edit | edit source]

Based on new evidence, traditional beliefs about the effects of exercise on lymphoedema have been disproven. MacMillan Cancer Support[42] state that many individuals experience reduced quality of life following cancer treatment due to secondary complications, which can include lymphoedema. Despite the general well known benefits of exercise including reduced risk of chronic diseases and the positive impact it can have on mental health[43], studies report that cancer survivors often fail to return to their pre-diagnosis levels of physical activity[44][45].

Traditionally strenuous exercise was discouraged in patients with lymphoedema based on the belief that it may exacerbate the condition[46]. However recent studies and systematic reviews contradict this statement. Cancer Research UK provides an informative section on their website for people with lymphoedema. Normal use of the limb can be sufficient to assist lymphatic flow but even normal use may be restricted in palliative patients. Pain, weight of the limb, fatigue or neurological impairment will impact limb mobility. Relatives and carers could assist in some passive exercises if tolerated. Elevation of the limb will help reduce the gravitational component of the swelling, e.g. supporting the arm on a pillow or cushion to prevent pooling at the elbow[18]. Aerobic activities to stimulate lymphatic return should be encouraged within the patients tolerance. Aerobic exercise minimises psychological distress and fatigue among cancer patients, even those with advanced and widely spread disease[17].

The following table summarises some of the studies that have been conducted surrounding this topic.

| Study Title | Design | Participants | Intervention | Outcome Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of Upper Extremity Exercise on Secondary Lymphedema in Breast Cancer Patients: A Pilot Study[47] | Pilot study | 14 breast cancer survivors with unilateral upper limb lymphoedema | Progressive upper body exercise programme – 8 weeks vs. no intervention | Arm circumference and volume Medical Outcomes Trust Short From 36 – survey |

No changes in lymphoedema Physical, general and vitality components of QOL improved |

| Exercise and Secondary Lymphedema: Safety, Potential Benefits, and Research Issues[48] | RCT | 32 breast cancer survivors with lymphoedema | Mixed type exercise programme – 12 weeks vs. no intervention | Bioimpedence spectroscopy and perometry | No changes – did not exacerbate lymphoedema |

| Weight lifting in Women with Breast-Cancer-Related Lymphoedema[49] | RCT | 141 breast cancer survivors with stable arm lymphoedema | 2x weekly progressive weight lifting vs. no intervention | Severity of lymphoedema, number and Incidence of exacerbations and symptoms and muscle strength | No effect on limb swelling, reduced exacerbations and symptoms, increased muscle strength |

| Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Exercise for Those With Cancer-Related Lymphoedema[50] | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Individuals with secondary lymphoedema 25 studies included |

Range of exercises | Lymphoedema and associated symptoms | No effect on lymphoedema or associated symptoms Insufficient evidence for use of compression during exercise |

| Exercise in patients with lymphedema: a systematic review of the contemporary literature[51] | Systematic review | Cancer patients with or at risk of lymphoedema 19 studies included |

Range of exercises | Lymphoedema development and exacerbations | No development or exacerbation of lymphoedema |

| Weight training is not harmful for women with breast cancer-related lymphoedema: a systematic review[52] | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Women with or at risk of developing breast cancer related lymphoedema 11 studies included |

Progressive weight training exercise | Severity and incidence of arm lymphoedema, upper limb muscle strength, BMI and QOL | Increased strength without affecting arm volume or incidence of lymphoedema No effect on BMI Potential to improve some elements of QOL |

The studies in the table above used a range of different exercise modes, there is little evidence to recommend the optimal mode of exercise for people with lymphoedema; therefore larger scale trials are required to evaluate this. However, the most recent systematic review discussed that by giving people a choice over their exercise method promoted adherence to the programme[52].

Singh et al.[50] also reviewed the use of compression garments during exercise. Unfortunately due to the range of effects that wearing compression can have during exercise, there was no definitive answer to whether compression garments should be worn or not. The authors suggest that this decision should be made on an individual basis considering factors such as stage, severity, and stability of lymphoedema and patient preference.

Evidence suggests that exercise supervised by a qualified professional i.e. a physiotherapist in the first instance - this will ensure correct technique and reduce injury risk[51]. It can be concluded from the body of evidence including large randomised controlled trials and recent systematic reviews that strenuous training, as previously thought does not lead to the development or worsening of lymphoedema. Despite showing little effect on lymphoedema, it is important to note the benefits that exercise has on individual’s strength, functioning and quality of life. These benefits outweigh any risks that were previously suggested.

Manual and Simple Lymphatic Drainage[edit | edit source]

Manual lymph drainage (MLD) is highly effective in the palliative setting. It has pain relieving properties and can significantly clear even tight, malignant oedema. MLD should avoid areas of dermal compromise, cancerous invasion, extensive fibrosis, or skin hypersensitivity. However, if MLD has been found to be effective over such areas, the treatment should be continued as the main aim of palliative care is to better a patient’s comfort and quality of life[17].

Emil Vodder came up with the method of manual lymphatic drainage (MLD) in 1936. He stated that MLD along with other techniques such as deep breathing and improved diet would play a key role in lymphatic conditions [53]. This method of massage uses gentle strokes to enhance lymph drainage through lymphatic pathways[28]. The treatment alone is not sufficient to reduce lymphoedema, however it is recommended that MLD is conducted by trained professionals in conjunction with the other components of DLT, which have been discussed previously[28].

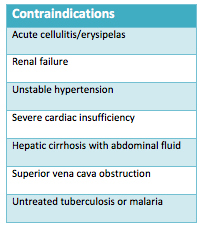

Below the tables show the indications, contraindications and local contraindications of MLD[28].

The principles and technique of MLD are stated below[53][28]:

- Slow repetitive movements

- Moves proximally to distally

- Aims to increase lymph drainage without altering capillary function

- Alter interstitial pressures by varying hand movements

- Incorporates breathing techniques (deep diaphragmatic breathing) to encourage drainage from deep abdominal lymph nodes and vessels

- Up to one hour daily

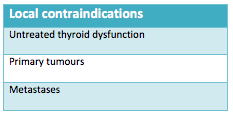

As well as MLD, another form of this treatment is known as Simple Lymphatic Drainage (SLD) - a simplified version of MLD that can be taught to people with lymphoedema or their carers to form part of a self-management programme. MLD can be performed for up to one hour daily, however SLD is performed for 10-20 minutes[54]. Prior to teaching SLD to individuals, health professionals must consider:

Supporting Evidence[edit | edit source]

MLD has been found to reduce limb volume, improve quality of life and lymphoedema symptoms in people with cancer related lymphoedema[55]. However, this study had a number of flaws limiting its quality, indicating the need for further research in this area. When comparing MLD to SLD, Sitzia et al.[56] suggests MLD to be more beneficial at reducing limb swelling. However these results were from a small pilot study and did not reach statistical significance.

A more recent systematic review[57] evaluated the effects of MLD in preventing and treating breast cancer related lymphoedema. Overall the findings from this review were unable to support the use of MLD in the prevention or treatment of lymphoedema in this patient group.

Although the evidence discussed was unable to support the use of MLD and SLD to treat lymphoedema, the Lymphoedema Framework[28] still recommend it as one of the cornerstones of decongestive lymphatic therapy. The framework suggests that despite the efficacy not being proven, MLD and SLD both have clear psychological and symptomatic benefits. Pyke[54] discussed that massage can reduce fear and reassure patients that although their skin is painful and may be damaged it can still be touched.

Overall it can be concluded that further evidence is required to fully evaluate the benefits of MLD or SLD in the management of lymphoedema. The benefits may not reach statistical significance but the impact that MLD or SLD could have on an individual’s quality of life are important to consider. Furthermore SLD, although little evidence to support its use, allows the patient some independence as they are able to take some responsibility for the management of their condition.

Traditionally lymphoedema is managed with DLT and is based on four pillars of care: compression, massage, skin care and exercise[28]. However, routine intensive management using decongestive lymphatic therapy may not be appropriate due to weakness and frailty so this must be modified and adapted[18]. Please refer to the previous section about treatment and management of lymphoedema if you need to refresh your memory of the four components of DLT.

In a palliative setting, physiotherapists need to approach lymphoedema management with an understanding that disease processes are dynamic and may progress rapidly. In order to offer patients long-term relief, the chosen treatment plan must also have the ability to adapt quickly therefore treatment must be feasible and flexible. Therefore, DLT is modified to suit the needs of a palliative patient.

Modified DLT has the capacity to significantly benefit patients with far advanced disease who have lymphoedema or multi-factorial oedema. DLT can enhance patients’ function and comfort while preventing needless complications and enhancing psychological well-being [17].

Additional Resources[edit | edit source]

Here are some additional resources that may benefit you as a future clinician. These may be of use when explaining the condition and treatment to patients or family. Furthermore, they are good sources of information to direct patients or family to if they wished for additional information at home.

- NHS Information[58][60][67][29][29][28][28]

- Bupa Cromwell Hospital patient information[59][61][68][109][109][108][108]

- Lymphoedema Support Network[60][62][69][110][110][109][109]

- Cancer Research UK[61][63][70][111][111][110][110]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Seifter j, Ratner A, Sloane D. Concepts in Medical Physiology. London: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

- ↑ National Lymphedema Network. What is Lymphedema? http://www.lymphnet.org/le-faqs/what-is-lymphedema (accessed 11 January 2016).

- ↑ Ridner SH. Pathophysiology of lymphedema. Semin Oncol Nurs 2013;29:4-11. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23375061 (accessed 26 January 2016).

- ↑ Foldi M, Foldi E. Foldi’s Textbook of Lymphology. 2nd ed. Germany: Elsevier, 2006.

- ↑ Hampton S. Lymphoedema: a common but often misunderstood condition. Nurs Residential 2015;17:492-497. http://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=69d3e2eb-40db-4061-a94d-3902bd3bb3b2%40sessionmgr4001&vid=9&hid=4207 (accessed 7 October 2015)

- ↑ Kerchner K, Fleischer A, Yosipovitch G. Lower extremity lymphedema: Update: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment guidelines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:324-331. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0190962208004842 (accessed 12 January 2016)

- ↑ Beck M, Wanchai A, Stewart BR, Cormier JN, Armer JM. Palliative care for cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review. Journal of palliative medicine. 2012 Jul 1;15(7):821-7.

- ↑ World Health Organisation. Palliative Care. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs402/en/ (accessed 23 Jan 2016).

- ↑ NHS National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Improving Supportive and Palliative Care for Adults with Cancer. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/csg4 (accessed 30 Nov 2015).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Clark D. From margins to centre: a review of the history of palliative care in cancer. Lancet Oncol 2007;8:430–38. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1470204507701389 (accessed 26 January 2016).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Baines M. From pioneer days to implementation: lessons to be learnt. Abridged version: European Journal of Palliative Care 2011;18(Suppl 5):223-227. http://www.eapcnet.eu/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=2qKGRm3iOpk%3d&tabid=167 (accessed 30 December 2015)

- ↑ MacMillan Cancer Support. Organisation and History. https://www.macmillan.org.uk/about-us/who-we-are/organisation-history.html (accessed 25 January 2016).

- ↑ Marie Curie. Our History. https://www.mariecurie.org.uk/who/our-history (accessed 25 January 2016).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Sheikh A. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ 2005;330:1007-1011. http://www.bmj.com/content/330/7498/1007 (accessed 21 Nov 2015).

- ↑ World Health Organisation Europe. The Solid Facts: Palliative Care. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/98418/9E82931.pdf (accessed 26 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Wikimedia Commons. Pathological Steps of Cancer Related Lymphoedema, Histological Changes in the Collecting Lymphatic Vessels after Lymphadenectomy. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pathological_Steps_of_Cancer_Related_Lymphedema,_Histological_Changes_in_the_Collecting_Lymphatic_Vessels_after_Lymphadenectomy1.png (accessed 8 January 2016).

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 17.7 17.8 17.9 ILF. The management of lymphoedema in advanced cancer and oedema at the end of life. http://www.lympho.org/mod_turbolead/upload/file/Palliative%20Document%20-%20protected.pdf (accessed 11 October 2015).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 Todd M. Managing lymphoedema in palliative care patients. British journal of nursing 2009;8(Suppl 8):466-472. http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Marie_Todd/publication/24308357_Managing_lymphoedema_in_palliative_care_patients/links/0c96052a1aded1e3a3000000.pdf (accessed 17 December 2015).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Todd M. Understanding lymphoedema in advanced disease in a palliative care setting. International Journal of Palliative Nursing 2009;15(Suppl 10):474-480. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20081719 (accessed 17 December 2015).

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 National Cancer Action Team. Holistic needs assessment for people with cancer. http://www.ncsi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Holistic-Needs-Assessment-practical-guide.pdf (accessed 11 December 2015).

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 National Cancer Survivorship Initiative. Holistic needs assessment. http://www.ncsi.org.uk/what-we-are-doing/assessment-care-planning/holistic-needs-assessment/ (accessed 11 December 2015).

- ↑ Macmillan. Holistic Needs Assessment and Care Planning. http://be.macmillan.org.uk/Downloads/CancerInformation/SGPwinter2012hna.pdf (accessed 5 Dec 2015).

- ↑ CSP. Outcome measures. http://www.csp.org.uk/professional-union/practice/evidence-base/outcome-measures (accessed 20 January 2016).

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Frymark U, Hallgren L, Reisberg A. Physiotherapy in palliative care – a clinical handbook. Sweden: Stockholms Sjukhem, 2009.

- ↑ Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Physiotherapy Works: Lymphoedema. http://www.csp.org.uk/publications/physiotherapy-works-lymphoedema (accessed 20 January 2016).

- ↑ Chang CJ, Corimer JN. Lymphoedema Interventions: Exercise, Surgery and Compression Devices. Seminars in Oncology Nursing 2013;29(Suppl 1):28-40. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23375064 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Kim SJ, Park YD. Effects of complex decongestive physiotherapy on the oedema and the quality of life of lower unilateral lymphoedema following treatment for gynaecological cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care 2007;17:463-468. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18637114 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ 28.00 28.01 28.02 28.03 28.04 28.05 28.06 28.07 28.08 28.09 28.10 28.11 28.12 28.13 28.14 28.15 28.16 28.17 28.18 28.19 28.20 28.21 Lymphoedema Framework. Best Practice for the Management of Lymphoedema. International consensus. http://www.woundsinternational.com/media/issues/210/files/content_175.pdf (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ Korpan ML, Crevenna R, Fialka-Moser V. Lymphedema A Therapeutic Approach in the Treatment and Rehabilitation of Cancer Patients. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2011; 90(Suppl 5):69-75. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21765266 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ Cooper G. Compression therapy in oedema and lymphoedema. British Journal of Cardiac Nursing 2015;8(Suppl 11):547-551. http://www.magonlinelibrary.com/doi/10.12968/bjcn.2015.20.3.118 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 European Wound Management Association. Lymphoedema bandaging in practice. http://ewma.org/fileadmin/user_upload/EWMA/pdf/Position_Documents/2005__Lymphoedema/English_focus_doc_05.pdf (accessed 16 January 2016).

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Lymphoedema Framework. Best Practice for the Management of Lymphoedema – 2nd Edition. Compression Therapy: A position document on compression bandaging. http://www.lympho.org/mod_turbolead/upload/file/Resources/Compression%20bandaging%20-%20final.pdf (accessed 17 January 2016).

- ↑ Badger CMA, Peacock JL, Mortimer PS. A Randomised, Controlled, Parallel-Group Clinical Trial Comparing Multilayer Bandaging Followed by Hosiery versus Hosiery Alone in the Treatment of Patients with Lymphedema of the Limb. Cancer 2000;88(12):2832-2837. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10870068 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Lamprou, DAA, Damstra RJ, Partsch H. Prospective, Randomised, Controlled Trial Comparing a New Two-Component Compression System with Inelastic Multicomponent Compression Bandages in the Treatment of Leg Lymphoedema. Dermatologic Surgery 2011;37(Suppl 7):985-991. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22002586 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ Franks PJ, Moffatt CJ, Murray S, Reddick M, Tilley A, Schreiber A. Evaluation of the performance of a new compression system in patients with lymphoedema. International Wound Journal 2012;203-209. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22432947 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ Moffatt CJ, Franks PJ, Hardy D, Lewis M, Parker V, Feldman JL. A preliminary randomised controlled study to determine the application frequency of a new lymphoedema bandaging system. British Journal of Oncology 2012;166(Suppl 3):624-632. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22059933 (accessed 20 January 2016).

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Doherty D, Morgan P, Moffatt C. Hosiery in lower limb lymphoedema. Journal of Lymphoedema 2009;4(Suppl 1):30-37. http://www.journaloflymphoedema.com/ (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ Linnitt N, Davies R. Fundamentals of compression in the management of lymphoedema. British Journal of Nursing 2007;16(Suppl10):588-592. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17577161 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ Wigg J, Lee N. Managing lymphoedema and chronic oedema. Nursing and Residential Care 2015;17(Suppl 4):192-197. http://www.magonlinelibrary.com/doi/10.12968/nrec.2015.17.4.192 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 40.4 40.5 Nowicki J, Siviour A. Best Practice skin care management in lymphoedema. Wound Practice and Research 2013;21(Suppl 2):61-65. http://www.awma.com.au/journal/2102_03.pdf (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ James S. What are the perceived barriers that prevent patients with lymphoedema from continuing optimal skin care? Wound Practice and Research 2011;19(Suppl 3):152-158. http://www.awma.com.au/journal/1903_09.pdf (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ MacMillan Cancer Support. Cured – but at what cost? http://www.macmillan.org.uk/Documents/AboutUs/Newsroom/Consequences_of_Treatment_June2013.pdf (accessed 16 January 2016).

- ↑ NHS Choices. Benefits of Exercise. http://www.nhs.uk/Livewell/fitness/Pages/Whybeactive.aspx (accessed 16 January 2016).

- ↑ Irwin ML, Crumley D, McTieran A, Bernstein L, Baumgartner R, Gilliand F, Kriska A, Ballard-Barbash R. Physical Activity Levels before and after a Diagnosis of Breast Carcinoma, The Health, Eating, Activity and Lifestyle (HEAL) Study. Cancer 2003;97(Suppl 7):1746-1757. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12655532 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ Harrison S, Hayes SC, Newman B. Level of physical activity and characteristics associated with change following breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. Psycho-Oncology 2009;18:387-394. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pon.1504/references (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ Cheifetz O, Haley L. Management of secondary lymphoedema related breast cancer. Canadian Family Physician 2010;56:1277-1284. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21375063 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ McKenzie DC, Kalda AL. Effect of Upper Extremity Exercise on Secondary Lymphedema in Breast Cancer Patients: A Pilot Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2003;21(Suppl 3):463-466. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12560436 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ Hayes SC, Reul-Hirche H, Turner J. Exercise and Secondary Lymphedema: Safety, Potential Benefits, and Research Issues. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 2009;483-489. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19117320 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel A, Cheville A, Smith R, Lewis-Grant L, Bryan CJ, Williams-Smith CT, Greene QP. Weight lifting in Women with Breast-Cancer-Related Lymphoedema. The New England Journal of Medicine 2009;361:664-673. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19675330 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Singh B, Disipio T, Peake J, Hayes SC. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Exercise for Those With Cancer-Related Lymphoedema. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2015;1-30. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26440777 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Kwan M, Cohn JC, Armer JM, Stewart BR, Corimer N. Exercise in patients with lymphedema: a systematic review of the contemporary literature. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 2011;5:320-336. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22002586 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Paramanandam VS, Roberts D. Weight training is not harmful for women with breast cancer-related lymphoedema: a systematic review. Journal of Physiotherapy 2014;60:136-143. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25086730 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Williams A. Manual lymphatic drainage: exploring the history and evidence base. British Journal of Community Nursing 2010;18-24. Available from: http://www.magonlinelibrary.com/doi/abs/10.12968/bjcn.2010.15.Sup3.47365 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Pyke C. Massage: a helping hand for people with chronic oedema and lymphoedema. Clinical Focus 2010:28-30. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20559174 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ Williams AF, Vadgama A, Franks PJ, Mortimer PS. A randomised controlled crossover study of manual lymphatic drainage therapy in women with breast cancer-related lymphodema. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2002;11(4):254-261. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12492462 (accessed 18 January 2015)

- ↑ Sitzia J, Sobrido L, Harlow W. Manual lymphatic drainage compared with simple lymphatic drainage in the treatment of post-mastectomy lymphoedema: A pilot randomised trial. Physiotherapy 2002; 88(2):99-107. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0031940605609339 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ Huang TW, Tseng SH, Lin CC, Bai CH, Chen CS, Hung CS, Wu CH, Tam KW. Effects of manual lymphatic drainage on breast cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. World Journal of Surgical Oncology 2013;11(15). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23347817 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ NHS. Lymphoedema. http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/Lymphoedema/Pages/Introduction.aspx (accessed 26 January 2015).

- ↑ Bupa Cromwell Hospital. Lymphoedema – a patient guide. http://www.bupacromwellhospital.com/easysiteweb/getresource.axd?assetid=1005&type=0&servicetype=1 (accessed 26 January 2016).

- ↑ The Lymphoedema Support Network. What is Lymphoedema? http://www.lymphoedema.org/Menu3/Index.asp (accessed 26 January 2016).

- ↑ Cancer Research UK. What is Lymphoedema? http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/coping-with-cancer/coping-physically/lymphoedema/what-is-lymphoedema (accessed 26 January 2016).