Tension-type headache

Original Editor - Rachael Lowe

Top Contributors - Laure Lievens, Admin, Fasuba Ayobami, Emma Guettard, Vanessa Rhule, Astrid Lahousse, Kim Jackson, Elaine Lonnemann, Kapil Narale, Jacquelyn Brockman, Vidya Acharya, Ahmed M Diab, Grite Apanaviciute, Anouk Van den Bossche and Jonathan Wong

[edit | edit source]

Definition/Description

[edit | edit source]

Tension-type headache is a neurological disorder characterized by a predisposition to attacks of mild to moderate headache with few associated symptomsCite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title.The criteria for tension-type headache outlined in the IHS classification will be mentioned in the subtitle ‘Diagnostic Procedures’.

This is the most common type of primary headache: its lifetime prevalence in the general population ranges in different studies from 30 to 78%. At the same time, it is the least studied of the primary headache disorders, despite the fact that it has the highest socio-economic impact.

Tension-type headaches are divided into;

- Infrequent episodic

The infrequent subtype has episodes less than once per month and has very little impact on the individual. The pain is typically bilateral, pressing, or tightening in quality and mild to moderate intensity. It does not worsen with physical activity. There is no nausea, but photophobia or phonophobia may be present.

- Frequent episodic

Frequent sufferers(between one and fifteen days a month) can encounter considerable disability that sometimes warrants expensive drugs and prophylactic medication. This frequent form is a physiologic response to stress, anxiety, depression, emotional conflicts, fatigue or repressed hostility.

- Chronic tension-type headaches.

The chronic subtype evolves over time from episodic tension-type headache and causes greatly decreased quality of life and high disability. It is diagnosed if headaches occur 15 days a month (180 or more days a year).Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

The exact mechanisms of tension-type headache are not known. Peripheral pain mechanisms are most likely to play a role in Infrequent episodic tension-type headache and Frequent episodic tension-type headache whereas central pain mechanisms play a more important role in Chronic tension-type headache.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

[edit | edit source]

The underlying cause of tension-type headache is uncertain. The most probably explanation for Infrequent episodic tension-type headache is activation of hyperexcitablehyper excitable peripheral afferent neurons from head and neck muscles. Muscle tenderness and psychological tension are associated with and aggravate tension-type headache but are not clearly its cause. Abnormalities in central pain processing and generalised increased pain sensitivity are present in some patients with tension-type headache, often the chronical type. Susceptibility to tension-type headache is influenced by genetic factors.

Epidemiology /Etiology

[edit | edit source]

The patient can either be given only the tension-type headache diagnosis or be given both the tension-type headache diagnosis and a secondary headache diagnosis, according to another disorder that is causing the headache with characteristics of tension type headache. Factors that characterize the secondary headache diagnosis are: a very close temporal relation to the disorder, a marked worsening of the tension-type headache, very good evidence that the disorder can cause or aggravate tension-type headache and improvement or resolution of tension-type headache after relief from the disorder.

TTH is the most common type of primary headache. Lifetime prevalence in the general population ranges in different studies from 30 to 78%. 3

Loder et al summarizes that the mean lifetime prevalence of tension-type headache in adults, based on pooled results from five population based studies, is 46%. The prevalence peaks at age 40-49 years in both sexes. The female to male ratio is about 5:4.1

In a review of Stovner J. L. et al from 2010, nineteen studies have reported the prevalence of current tension type headache in Europe. Among 66,000 adults, 62.6% had episodic TTH, and 3,3% had chronic TTH. Prevalence of children and youth is less, about 15.9% TTH and 0.9% chronic TTH. The studies where done in Croatia, Denmark, Georgia, Germany, Norway, Portugal, Turkey, Finland, Serbia and Sweden.4 Data on TTH is still too scarce in Europe. The female preponderance of chronic TTH is greater than that of episodic, but lower than that of migraine. The prevalence of CTTH increases with age, according to Schwartz BS et al (1998)5. The prevalence of episodic tension type headache increases with educational level.1

The International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) is a detailed hierarchical classification of all headache-related disorders published by the International Headache Society. It was in 1988, in the ICHD-1, that tension-type headache was divided into episodic and chronic subtypes.

The first edition arbitrarily separated patients with and without disorder of the pericranial muscles. The only really useful feature to subdivide all three subtypes of tension-type headache is tenderness on manual palpation and not, as suggested in the first edition, evidence from surface EMG or pressure algometry.

In the second edition of this classification(2004) there was an attempt to precise the diagnostic criteria for tension-type headache, with the hope to exclude migraine patients whose headache phenotypically resembles tension-type headache. 3 (level of evidence 2A)

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation

[edit | edit source]

Infrequent episodic tension-type headache[edit | edit source]

Infrequent episodes of headache lasting minutes to days. The pain is typically bilateral, pressing or tightening in quality and of mild to moderate intensity, and it does not worsen with routine physical activity. There is no nausea but photophobia or phonophobia may be present.

Frequent episodic tension-type headache[edit | edit source]

Frequent episodes of headache lasting minutes to days. The pain is typically bilateral, pressing or tightening in quality and of mild to moderate intensity, and it does not worsen with routine physical activity. There is no nausea but photophobia or phonophobia may be present.

Frequent tension-type headache often coexists with migraine without aura. Coexisting tension-type headache in migraineurs should preferably be identified by a diagnostic headache diary. The treatment of migraine differs considerably from that of tension-type headache and it is important to educate patients to differentiate between these types of headaches in order to select the right treatment and to prevent medication-overuse headache.

Chronic tension-type headache[edit | edit source]

A disorder evolving from episodic tension-type headache, with daily or very frequent episodes of headache lasting minutes to days. The pain is typically bilateral, pressing or tightening in quality and of mild to moderate intensity, and it does not worsen with routine physical activity. There may be mild nausea, photophobia or phonophobia.

Differentiation between this and Chronic migranemigraine can be difficult. It should be remembered that some patients with chronic tension-type headache develop migraine-like features if they have severe pain and , conversely, some migraine patients develop increasingly frequent tension-type-like interval headaches, the nature of which remains unclear.3

Differential Diagnosis

[edit | edit source]

Differential diagnosis TTH and migraine:[edit | edit source]

Some combinations of symptoms make diagnosis of migraine certain, such as unilateral location, severe intensity, pain aggravation by physical activity. While there are other combinations that make the TTH diagnosis certain, such as bilateral location, pressing-tightening quality, mild intensity, no aggravation by physical activity. Most of the overlap between the different types of headache can be differentiated as ETTH or MWA by applying recommended combinations: “migrainous location, severe intensity, aggravation by physical activity”, “severe intensity and nausea”,for the diagnosis of migraine and “no nausea and no photophobia”, “bilateral location, mild intensity and either no aggravation by physical activity or pressing-tightening quality for the diagnosis of TTH.6 (level of evidence 2B)

Some other differential diagnosis :[edit | edit source]

Medication-overuse headache: History of previous primary headache. Use of analgesics and ergotamine at a high frequency and worsening of headache on discontinuation of medication. Over several months, frequency and duration increases such that attacks become daily or near daily, although not necessarily more severe. Opioids and barbiturate-containing analgesics most commonly produce this syndrome.

Sphenoid sinusitis: Vertex or frontal pain, often described as pressure, but not necessarily with additional sinus symptoms.

Giant cell arteritis: Generally over 50 years of age. New head pain associated with soreness of the scalp; polymyalgia rheumatica and often jaw or tongue claudication.

Temporomandibular disorder (TMD): Pain over temporalis associated with noise and clicking over TMJ with jaw movement. Often associated with bruxism and limited jaw movements, or pain or locking of the jaw with opening of mouth.

Pituitary tumor: Abnormal neurologic examination. Visual field defects and galactorrhea may occur.

Brain tumor: Abnormal neurologic examination including reflex asymmetry, sensory asymmetry, or motor weakness. Papilledema suggests an intracranial mass lesion.

Chronic subdural hematoma: Abnormal mentation, abnormal neurologic examination including reflex asymmetry, sensory asymmetry, or motor weakness.

Pseudotumor cerebri (idiopathic intracranial hypertension): As well as papilledema, there may be reduced visual acuity, visual field defect (enlarged blind spot), or diplopia caused by a sixth nerve palsy. CSF pressures are abnormal and are increased to >200 mm water in nonobese and >250 mm water in obese people.

Cervical pathology: Rarely, serious cervical pathology such as a herniated disk may contribute to headache 3,7

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic criteria for the 3 subtypes of tension-type headache from the IHS classification

Diagnostic criteria for Infrequent episodic tension-type headache:[edit | edit source]

1. At least 10 episodes occurring on <1 day per month on average (<12 days per year) and fulfilling criteria 2-4

2. Headache lasting from 30 minutes to 7 days

3. Headache has at least two of the following characteristics:

-bilateral location

-pressing/tightening (non-pulsating) quality

-mild or moderate intensity

-not aggravated by routine physical activity such as walking or climbing stairs

4. Both of the following:

-no nausea or vomiting (anorexia may occur)

-no more than one of photophobia or phonophobia

5. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis.

Diagnostic criteria for Frequent episodic tension-type headache:[edit | edit source]

1. At least 10 episodes occurring on ≥1 but <15 days per month for at least 3 months (≥12 and <180 days per year) and fulfilling criteria

2. Headache lasting from 30 minutes to 7 days

3. Headache has at least two of the following characteristics:

-bilateral location

-pressing/tightening (non-pulsating) quality

-mild or moderate intensity

-not aggravated by routine physical activity such as walking or climbing stairs

4. Both of the following:

-no nausea or vomiting (anorexia may occur)

-no more than one of photophobia or phonophobia

5. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis.

Diagnostic criteria for Chronic tension-type headache:[edit | edit source]

1. Headache occurring on ≥15 days per month on average for >3 months (≥180 days per year)1 and fulfilling criteria 2-4

2. Headache lasts hours or may be continuous

3. Headache has at least two of the following characteristics:

-bilateral location

-pressing/tightening (non-pulsating) quality

-mild or moderate intensity

-not aggravated by routine physical activity such as walking or climbing stairs

4. Both of the following:

-no more than one of photophobia, phonophobia or mild nausea

-neither moderate or severe nausea nor vomiting

5. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

1) HARDSHIP: The Headache-Attributed Restriction, Disability, Social Handicap and Impaired Participation questionnaire which is designed for application by medical or trained interviewers. HARDSHIP integrates diagnostic questions (these are based on ICHD-3 β criteria), demographic enquiry and investigate the several components of headache-attributed burden: symptom burden, health-care utilization, disability and productive time loss, the impact on education and earnings, perception of control, interictal burden, overall individual burden, effects on relationships and family, effects on other people including household partner and children, quality of life, wellbeing, obesity as a comorbidity. 84

2) Quality of life: WHOQoL-BREF (World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire-BREF). This is an shortened version of the WHOQoL-100 developed by The World Health Organization. It’s a self-report questionnaire that contains 26 items, these are subdivided into 4 QoL domains: psychological health, physical health, social relationships, environment and two other items which measure general health and overall QoL. 9

3) The Headache Impact Test-6 questionnaire (HIT-6): this questionnaire evaluates the impact of headache on the quality of life.10

Examination[edit | edit source]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

After appropriately diagnosing TTHs, medical professionals must then determine what the most effective treatment is for these headaches. Due to the lack of knowledge of concerning the etiology of TTHs, they are very difficult to treat. Medical professionals try to incorporate patient education, lifestyle modifications, and cost-effective medications into their treatments.11 An example of a lifestyle modification would be discussing smoking cessation with one’s patient. There is a strong positive correlation between how many cigarettes are smoked and how many days out of the week patients experience headaches. Research has also found a positive correlation between high volumes of nicotine and higher anger, anxiety, and depression. Although drug therapy is finite in its ability to treat the underlying cause of TTHs, it has still been found to be effective in relieving symptoms of pain many patients.

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

A simple randomized controlled trail by D’Souza et al proved that relaxation therapy was effective to improve the headache frequency en also led to an immediate increase of calmness. But it was only a brief protocol with 3 months follow up so further investigation is necessary. [13] The review written by Wallash et al, confirms that there is a benefit for patients with TTH to participate in relaxation therapy, 1 hour a day, if they have severefrequent episodic chronicitheadachey(10days/month). [14] Quinn et al. found that muscle-specific massage therapy was a non-pharmacological intervention effective for reducing tension type headache. [15

To use acupuncture as pain relief in TTH, Linde K. et al reviewed 11 trails. The authors concluded that acupuncture could be a valuable non-pharmacological tool in patients with frequent episodes or chronic tension-type headaches.[16]

The use of spinal manipulations is quite controversial, especially when performed in the neck because of the reported adverse reaction and patients’ concerns about safety. The adverse reaction range from minor conditions such as stiffness and limitation in motion to more severe kind like permanent neurological deficits or dissection of vertebral arteries. A recent study of Castien et al reported that manual therapy is more effective than usual general practice care in reducing symptoms of chronic tension type headache. This practice care includes posture corrections and maintaining these. These corrections mostly apply in the frontal plane.[17]

A literature review of Victoria et aL shows us that physiotherapy with articulatory manual therapy, combined with cervical muscle stretching and massage are effective for this disease in different aspects related with TTH. No evidence was found of the effectiveness of the techniques applied separately. [18]

Other studies demonstrate the fact that spinal manipulations were effective for tension type headache included patients with the chronic condition. Therefore, spinal joint manipulation may be more effective in chronic than in episodic tension type headache.

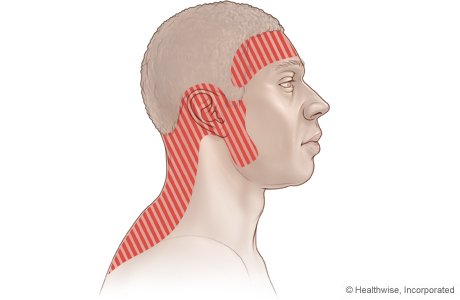

Fernandez-de-las-Penas et al suggest that when a patient with headache is mediated primarily by peripheral mechanisms (dominantly peripheral sensitization), early and appropriate local treatments and functional activity should be encouraged. In the appropriate local treatment ae massages and stretching techniques included. In a patient with frequent episodic tension type headache, a manual therapy approach including inactivation of active trigger points in the upper trapezius, sternocleidomastoid, temporalis, suboccipital, extra-ocular superior oblique or extraocular lateral rectus muscles, cervical mobilization/manipulation, and exercises targeted to the neck flexor or extensor synergy cooperation may be appropriate. Example of deep cervical flexor exercise: The patient is asked to gently nod the head as he/she was saying ‘yes’ without restoring to retraction, without strictly involvement of superficial flexors, and without a quick, jerky cervical flexion movement [19]

Despite all the positive findings, evidence-based guidelines recommend the application of spinal manipulations for migraine and cervicogenic headache, but not for tension type headache.

These inconsistency results in non-appropriate treatment of patients.

Key Research[edit | edit source]

Resources[edit | edit source]

- American. Physical Therapy. Association (APTA)

http://www.moveforwardpt.com/symptomsconditionsdetail.aspx?cid=fd8a18c8-1893-4dd3-9f00-b6e49cad5005

- World Health Organization

www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs277/en/

- University of Maryland Medical Center

umm.edu/health/medical/altmed/condition/tension-headache

- Lifting the Burden

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ The International Headache Society. International Classification of Headache Disorders II. Available from http://ihs-classification.org/en [last accessed 21/6/9]