Temporal Arteritis (Giant Cell Arteritis)

Original Editors - Students from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Kiersten Young, Savannah Lane, Lucinda hampton, Elaine Lonnemann, WikiSysop, 127.0.0.1, Kim Jackson and Sehriban Ozmen

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

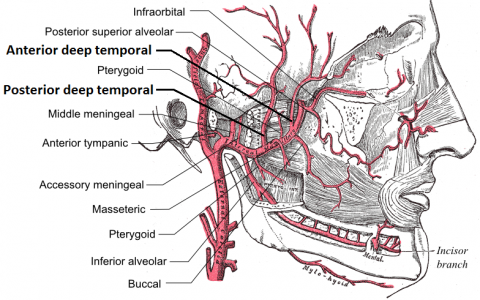

Temporal arteritis, also known as giant cell arteritis (GCA), is a systemic inflammatory vasculitis that affects medium-sized to large arteries.[1] The main arteries involved include the medium-sized muscular arteries, such as the cranial and extracranial branches of the carotid artery. This condition is known as a condition of the elderly and is a significant cause of secondary headache in older adults. GCA is closely linked to polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR), a systemic rheumatic inflammatory disorder with unknown causes[2]. GCA and PMR usually occur together in the same patient[1].

Prevalence

[edit | edit source]

GCA is the most frequent primary vasculitis, which predominantly affects Caucasian people over the age of 50[1][3]. 95% of cases occur in patients older than 55 years[4][5]. The incidence of GCA in 70-79 year olds is 29.6 per 100,000 individuals[6]. Women are 2-6 times more likely to be affected than men[1][5][7]. Giant cell arteritis occurs in at least 25% of all cases of polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR)[2]. GCA is more frequent among people of Scandinavian and Northern European descent[1][3].

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Headaches/ generalized head pain, decreased visual acuity, diplopia, decreased color vision, visual field defect, aching/ stiffness of joints, conjunctival hyperanemia, cough, corneal oedema, iritis, cranial symptoms such as jaw claudication, temporal artery tenderness, amaurosis fugax, decreased temporal pulse, and scalp pain present in the majority of cases [2][3][4][5][6].

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

- Polymyalgia Rheumatica (PMR)

- Visual Disturbances

- Facial pain

- Osteoporosis

- Hypokalemia

- Various infections such as oral/esophageal thrush

- Herpes Zoster[8]

Medications[edit | edit source]

High dose corticosteroids are the most widely accepted medication and overall treatment for GCA[1][7]. However, there is no consensus on dosage for either initial treatment or following rate of dosage reduction. Several entities such as the British Society for Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism have developed guidelines on dosing based off extensive literature search[6][9]- See "Medical Management" below.

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

GCA is diagnosed on the basis of the combination of symptoms, clinical findings, laboratory results, and diagnostic imaging[10].

- The gold standard diagnostic test for GCA is a temporal artery biopsy[4][5][7].

- Increased ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) >50 mm/h is one of the five American College of Rheumatology criteria for the diagnosis of GCA[5][6][7].

- CRP C-reactive protein is said to be increased in patients with GCA. It has been reported that CRP has a 100% sensitivity and when CRP is elevated in combination with ESR there is a 97% specificity[4][5][7].

- Thrombocytosis also serves as an important diagnostic tool for GCA. It has been shown that an elevated platelet may have a higher positive predictive value than ESR. In the setting of clinical suspicion and a raised ESR, thrombocytosis has a relatively high specificity for distinguishing GCA from other diseases[7].

- Plasma fibrinogen[5]

- Newer diagnostic modalities, including ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography can play an important role in directing treatment in cases with negative TAB[4][6].

American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for giant cell arteritis- at least three of five must be met[1][3][7]

1. Age at onset 50 years or more

2. New-onset headache or localized headache

3. Tenderness or decreased pulsation in at least one of the temporal arteries

4. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate 50 mm/h or more

5. Abnormal artery biopsy with either mononuclear cell infiltrate or granulomatous inflammation (with giant cells)

Etiology/Causes[edit | edit source]

The overall etiology of GCA is unkown[3]. Environmental factors are suspected to be potential triggers for this disease[1][10].

It is believed that the basis for the disease involves abnormalities of the arterial elasticum, with a decreased in integrity of the inner elastic membrane of affected arteries, resulting in a giant cell reaction near this elasticum.

Another theory is that the initial lesion is a destruction of the muscular layers of the artery’s tunica media caused by ischemia, which leads to fragmentation of the elasticum with formation of giant cells occurring secondarily[5].

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

Less common symptoms affecting only about eight percent of those with the condition include: pleural effusion, coronary vasculitis, pericarditis, myocarditis, peripheral neuropathy, hearing loss, renal arteritis, lymph node hyperplasia, and abnormal liver function, mesenteric ischemia, sore throat, choking sensation.

Constitutional symptoms may include weight loss, malaise, fever, depression, and polymyalgia rheumatica, night sweats[1][5][6][10][4].

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

The goal of treatment is to minimize tissue damage caused by inadequate blood flow, and the most common route of management involves use of corticosteroids such as Prednisone. Below are dosage guidelines developed by the European League Against Rheumatism [1][5][6].

Initial steps:

Prednisone 40 mg to 60 mg daily;

intravenous methylprednisolone

500 mg – 1 g × 3 days if visual

compromise or neurologic symptoms.

Treatment should not be withheld

pending TAB results.

Next Steps:

Gradual taper of prednisone by 10 mg

every 2 weeks to 20 mg, then 2.5 mg

every 2 weeks to 10 mg, then 1 mg

every month[6]

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Physical Therapists should be aware of associated signs and symptoms and refer patients accordingly. Prompt initiation of treatment may prevent blindness and other ischemic related consequences.There are no current physical therapy treatment options for temporal arteritis and best management described in literature involves use of corticosteroids.

The most important thing for physical therapists to be aware of are the clinical examination findings that are often associated with GCA. These include palpation of the temporal artery, auscultation of arteries including the subclavian and axillary, and bilateral blood pressure determination, looking for a predominant unilateral vascular stenosis[10]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Central retinal artery occlusion

- Acute glaucoma

- Uveitic glaucoma

- Retrobulbar optic neuritis

- Orbital abscess

- Ophthalmic migraine

- Tolosa hunt syndrome

- Orbital and cavernous sinus compressive lesions

- Migraine headache

- Lyme disease

- Herpes zoster ophthalmicus

- Trigeminal neuralgia

- Diabetes

- Poorly Controlled hypertension

- Stress related disorders

- Angina pectoris [4][6]

Case Reports/ Case Studies[edit | edit source]

1. Colin G, Dupont M. Giant cell arteritis. Journal of the Belgian Society of Radiology. 2013;96(5):290.

http://br.ubiquitypress.com/articles/10.5334/jbr-btr.406/galley/403/download/

2. Lockhart M, Robbin M. Case 58: Giant Cell Arteritis1. Radiology. 2003;227(2):512-515.

http://pubs.rsna.org/doi/pdf/10.1148/radiol.2272010487

3. De Hertogh W, Vaes P, Versijpt J. Diagnostic work-up of an elderly patient with unilateral head and neck pain. A case report. Manual Therapy. 2013;18(6):598-601.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Chew S, Kerr N, Danesh-Meyer H. Giant cell arteritis. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2009;16(10):1263-1268

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Goodman C, Snyder T. Differential diagnosis for physical therapists. St. Louis, Mo.: Saunders/Elsevier; 2013.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Salvarani C, Cantini F, Hunder G. Polymyalgia rheumatica and giant-cell arteritis. The Lancet. 2008;372(9634):234-245.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Kawasaki A, Purvin V. Giant cell arteritis: an updated review. Acta Ophthalmologica. 2009;87(1):13-32.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 Gurwood A, Malloy K. Giant cell arteritis. Clinical and Experimental Optometry. 2002;85(1):19-26.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 Smith J, Swanson J. Giant Cell Arteritis. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2014;54(8):1273-1289.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Wang X, Hu Z, Lu W, Tang X, Yang H, Zeng L et al. Giant cell arteritis. Rheumatol Int. 2008;29(1):1-7.

- ↑ Petri H, Nevitt A, Sarsour K, Napalkov P, Collinson N. Incidence of Giant Cell Arteritis and Characteristics of Patients: Data-Driven Analysis of Comorbidities. Arthritis Care & Research. 2015;67(3):390-395

- ↑ Schmidt J, Warrington K. Polymyalgia Rheumatica and Giant Cell Arteritis in Older Patients. Drugs & Aging. 2011;28(8):651-666.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Ness T, Bley TA, Schmidt WA, Lamprecht P. The diagnosis and treatment of giant cell arteritis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013 May 23;110(21):376-86.