Surgery and General Anaesthetic

Original Editors - Students from Glasgow Caledonian University's Cardiorespiratory Therapeutics Project.

Top Contributors - Bo Lian Ho Sing, Lucinda hampton, Erin Froude, Michelle Lee, Chris Seenan, Kim Jackson, 127.0.0.1, Admin, George Prudden, Adam Vallely Farrell and Karen Wilson

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Surgery is the treatment of injuries or disorders of the body by incision or manipulation, often with the use of instruments[1].

General anaesthetic is medication used in surgery with the purpose being loss of consciousness[2]. When it comes to major surgery, such as upper abdominal surgery, general anaesthesic is required. General anaesthetics are used for the safety and comfort of the patient. There are four components to general anaesthesics: amnesia (partial or total memory loss), analgesia (the inability to feel pain), muscle relaxation and interruption of nerve propagation so that surgical trauma is not felt by the patient[3].

A post-operative pulmonary complication is "any pulmonary abnormality that produces identifiable disease or dysfunction that is clinically significant and adversely affects the clinical course of the patient"[5]. Post-operative pulmonary complications from general anesthesics and upper abdominal surgery include: suppressed diaphragmatic movement, decreased response by the ventilatory system, atelectasis (alveolar collapse), perfusion abnormalities, decreased muco-cilliary transport making the patient susceptible to infection, hypoxaemia, respiratory failure and respiratory distress syndrome[6].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

In 2013/14 there were 64% more operations completed by the NHS compared to ten years earlier (2003/2004), with an increase from 6.71m operations to 11.03m operations[7].

Scotland (2013/2014)[8]: 367 operating theatres in 46 hospitals, each theatre having been used for approximately 27 hours per week, the average annual running cost per theatre was £1.6 million.

England (2013/2014): with ~3000 operating theatres in England and ~19 000 surgeons practicing, the NHS spent about £4.3 billion, ~ 4.3% of the NHS budget[9].

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

Patients undergoing upper abdominal surgery are at higher risk of post-operative pulmonary complications than cardiothoracic, lower abdominal or peripheral surgery[5]. For upper abdominal surgery, once anaesthetized, respiratory suppression is caused by paralysis leading to the use of mechanical ventilation. Functional Residual Capacity (FRC) drops as soon as the general anaesthetic enters the body; this reduction in FRC is an important factor in the possible development of post-operative complications. Furthermore, the length of time FRC is maintained at a lower volume is incredibly important[5].

During major abdominal surgery, the patient is lying supine. Adults lying supine see a drop in FRC by 1L because of cephalic movement of the diaphragm[5]. This is secondary to cephalic movement of abdominal contents. When under general anaesthetic for surgery, FRC decreases further by 450 mL due to relaxation of the thoracic muscles leading to further cephalic movement of the diaphragm. There is also possible increase in thoracic blood volume[5]. This can lead to compression atelectasis.

The combination of mechanical ventilation, anaesthesia, and atelectasis yields an atypical pattern of ventilation. In addition to this, loss of the cough reflex and sigh mechanism, both incredibly important for muco-cilliary transport, adds to the abnormal ventilatory pattern[5]. Though mechanical ventilation has an affect on lung volumes, it cannot regain regular perfusion of oxygenated air.

Upon extubation, the after effects of general anaesthesia, supine lying, pain and opiates further the process of ventilation/perfusion mismatch and atelectasis.

Abnormal ventilatory patterns continue for up to 10 days post-operation. Day 1-2, the patient sees a worsening of FRC. FRC is the last of lung volumes to return to normal following surgery (~10 days post-operation)[5].

Arterial blood gases will also see an abnormal shift post-operation. Something of a ‘hangover’ effect follows general anaesthesia; the body’s ability to detect hyperaemia, acidosis and carbon dioxide is affected[5]. Normal homeostasis by increased ventilation may not occur leading to hypoxia.

Investigations[edit | edit source]

Prior to surgery, the patient must undergo a pre-operative assessment. This involves seeing a nurse or doctor who will ask the patient questions about their health, medical history, advise the patient on what to do before the surgery and where to report on the day [10]. They may also carry out some tests, such as, blood pressure (BP) and respiratory rate (RR) so that when assessing the patient after surgery, they have baseline measurements to compare against. The pre-assessment will highlight any contra-indications that could postpone the surgery procedure [10].

Investigations used for monitoring the patient after surgery could be chest x-rays, BP, HR, RR, ABG's and other observations noted. Surgery and general anaesthetic can lead to postoperative pulmonary complications so it is crucial that patients are monitored. Anaesthesia can have an effect on lung mechanics, lung defences and gas exchange, therefore a chest x-ray will help identify if there is a lung collapse or any consolidation[11]. A CT scan can also identify consolidation and atelectasis[12]. Postoperative hypoxaemia may be present, thus an analysis of an arterial blood sample allows a physiotherapist to monitor deterioration and identify respiratory failure[13]. Another possible effect of anaesthesia is an alteration in mucociliary clearance. This can be monitored using auscultation to determine where the secretions are (broad). Blood pressure can help determine cardiovascular status of the patient[13]. Other observations could be heart rate, respiratory rate and temperature as these can all be altered if the patient has an infection[12].

Signs & Symptoms Present Post Surgery[edit | edit source]

- Immobile - patient may have a catheter and be on a drip, have a stoma bag, feel nausea from the anaesthetic or if they had have had an epidural, motor blocks may be hampering the patients ability to move around after surgery.

- Drowsiness

- Nausea

- Pain - coming round from being under anaesthetic, the patient may feel sudden pain and anxiety. This may also affect their inability to breathe deeply as their breathing tends to change to shallow and rapid breathing, reducing their functional residual capacity, resulting in atelectasis.

- Lung collapse - during surgery functional residual capacity can also decrease and it is thought this is due to the relaxation of the muscles of the chest wall, a decrease in mucociliary function, cephalad movement of the diaphragm and an increase in thoracic blood volume. This results in atelectasis and blockage of the bronchioles due to secretions and then could result in further collapse. Lung collapse can occur within 15 minutes of surgery and can last up to 4 days after surgery. if this is not seen to, this increases the risk of infection.

- Diaphragmatic dysfunction - may not contract sufficiently for up to 7 days after

Physiotherapy and Other Management[edit | edit source]

Pre-operative Physiotherapy[11]

Trying to see a patient before surgery can be beneficial, however, it can also be difficult if its an emergency or could be due to time constrictions with the patients, particularly within the NHS.

A pre-operative assessment may include:

- an explanation of the role of the physiotherapist within the team

- the possible risks of surgery and the effects of general aneasthesia

- what will happen after the surgery

Some of these benefits to seeing a physiotherapist pre-operatively are:

- may reduce the patient's anxiety levels

- confidence could be gained

- the patient will have more knowledge on what is entailed before,during and after the surgery and how they may feel afterwards

- can prevent the risk of developing post-operative pulmonary complications

Post-operative Physiotherapy

The main problems found on assessment of a patient who has had major surgical procedure is reduced lung volume[11]. This could result in impaired gas exchange and airway clearance[11]. Other cardiovascular and respiratory effects are reduction in functional residual capacity, PaO2, VO2Max, cardiac output and stroke volume, and an increase in HR[11]. Thus the aim of the physiotherapist is to try and improve these problems. From the post-operative assessment a treatment plan will be developed.

- Mobilisation - important component that will improve lung volume, improve circulation thus helping remove secretions, decrease their stay in the hospital and will make it easier for the patient to remove secretions. Examples: walking around their bed or along the corridor. This can be progressed to marching on the spot and moving from their bed to the chair.

- Positioning - sitting up and changing positions regularly can help improve ventilation and removing secretions.

- deep breathing exercises - include thoracic expansion exercises, diaphragmatic breathing & maximal inspiration[11]. Can help reinflate the collapsed lung[11].

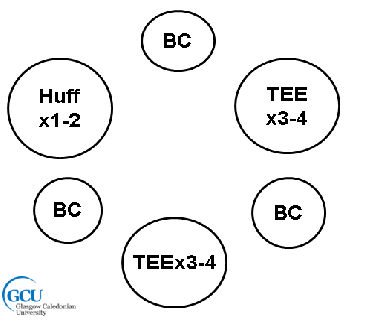

- Appropriate airway clearance techniques can be implemented, such as, active cycle of breathing techniques (ACBT) and autogenic drainage (AD)[12]. With surgery, more emphasis is on the deep breathing component rather than the forced expiratory manoeuvres to avoid pain and discomfort for the patient[11].Holding the breath and sniffing at the end of inspiration will help expand the lungs.

- Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) - assist with hypoxaemia, reduce RR & minute ventilation and also through to increase vital capactiy[11].

- Intermittent Positive Pressure - help improve lung volume and sputum retention

- Incentive spirometry - used to stimulate the patient to perform deep breathing exercises[11].

Management of Post-operative Pain

Pain after surgery can have a major effect on the patients recovery. Some of the effects are:

- ineffecitve ventilation

- poor cough

- inability to take deep breaths and sigh

- result in atelectasis, hypoxaemia and respiratory distress

- poor sleep

- delayed hospital charge

If their pain can be managed, this may result in a reduced length of stay in the hospital, reduce their length of rehabilitation and their rehabilitation will be more efficient[11].

Pain can be reduced through medication, education, careful handling and relaxation techniques[12] .

Different ways to administer drugs are:

- oral - codeine etc. they will sensitise nociceptor nerve endings and can reduce fever

- intra-muscular - morphine

- intra-venous - morphine, ketamine

- patient controlled analgesia - pethidine, fentanyl. very common method used to improve pain releif as it is not continuous so could prevent the risk of respiratory depression

- epidural - morhine, fentanyl

- peripheral blocks - bupivacaine. can block propogation of action potentials by blocking sodium channels

Other health professionals that are or could be involved in the patients recovery are:

- nurse - in the recovery room after surgery, a nurse can provide the patient with oxygen and offer medicine to relieve any pain or discomfort[10]

- consultant - regular check ups to make sure the patient is recovering well and will decide when the patient can be discharged

- GP - when the patient gets discharged, they may need to make regular visits to their GP for check-ups

- ocupational Therapist - depending what surgery was needed, an occupational therapist may be required to promote independant function into the patients life.

it is important that the physiotherapist is working with the patient when they are in least pain so they can get the best treatment, therefore it is recommended that the physiotherapist sees the patient 30 minutes after they have taken their medication.

Prevention[edit | edit source]

The main concerns after surgery are the risks of post-operative pulmonary complications and these can all be prevented if pain is managed and the patient is mobile.

However, other risk factors are associated with the risk of post-operative pulmonary complications[5]:

- Obesity

- Smoking - increases mucus production and is more difficult to clear, resulting in development of COPD and PPC

- COPD & Asthma

- Age - older aged people have deteriorated lung function and this is exacerbated with anaesthetics

- Poor nutrition - if 70% less than ideal body weight, can have weak respiratory muscles which can lead to protein depletion when undergoing anaesthetic, resulting in an increased risk of PPC

- Type of surgery - closer to the diaphragm, the greater the risk of a complication

- Use of oxygen - dry cold gases entering a warm humidifed area can result in increase in sputum viscosity and decrease mucociliary function which can increase bronchial secretions.

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ Oxforddictionaries.com. surgery - definition of surgery in English from the Oxford dictionary [Internet]. 2015 [cited 8 June 2015]. Available from: http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/surgery

- ↑ Nhsinform.co.uk. Anaesthetic, general | Definition | Health Library | NHS inform [Internet]. 2015 [cited 8 June 2015]. Available from: http://www.nhsinform.co.uk/health-library/articles/a/anaesthetic-general/definition/

- ↑ Norton J. Surgery. New York, NY: Springer; 2008.

- ↑ NHS Choices. Anaesthesia [Internet]. 2008 [cited 28 May 2015]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v-_Vz_6Ngrg

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 Blanchard M. Pre-operative risk assessment to predict post-operative pulmonary complications in upper abdominal surgery: a literature review. Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Respiratory Care. 2006;38:32-40.

- ↑ Kanat F, Golcuk A, Teke T, Golcuk M. RISK FACTORS FOR POSTOPERATIVE PULMONARY COMPLICATIONS IN UPPER ABDOMINAL SURGERY. ANZ J Surg. 2007;77(3):135-141.

- ↑ Nhsconfed.org. Key statistics on the NHS - NHS Confederation [Internet]. 2015 [cited 8 June 2015]. Available from: http://www.nhsconfed.org/resources/key-statistics-on-the-nhs

- ↑ Isdscotland.org. Finance | Costs | Specialty Costs | Theatres | ISD Scotland [Internet]. 2015 [cited 8 June 2015]. Available from: http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Finance/Costs/Detailed-Tables/Theatres.asp

- ↑ Rcseng.ac.uk. Surgery and the NHS in numbers — The Royal College of Surgeons of England [Internet]. 2015 [cited 8 June 2015]. Available from: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/media/media-background-briefings-and-statistics/surgery-and-the-nhs-in-numbers

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 NHS. Going into hospital. http://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/AboutNHSservices/NHShospitals/Pages/going-into-hospital.aspx#assessment (accessed 29th May 2015).

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 Denehy, L. Surgery for adults. In: Pryor, J.A, Prasad, S.A (eds.) Physiotherapy for Respiratory and Cardiac Problems. United Kingdom: Churchill livingstone; 2008. p. 397-439.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Hough, A. Physiotherapy in Respiratory and Cardiac Care - an evidence-based approach. (4th ed.). Singapore: Andrew Ashwin; 2014.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Broad, M. Cardiorespiratory Assessment of the Adult Patient: a Clinician's Guide. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2012

[[|]][[|]]