Stroke: The Role of Physical Activity

Original Editor - Priyanka Chugh

Top Contributors - Priyanka Chugh, Naomi O'Reilly, Admin, Kim Jackson, Wendy Walker, Venugopal Pawar, Vidya Acharya, Eugenie Lamprecht, Simisola Ajeyalemi and Rucha Gadgil

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Stroke is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide. In the UK, stroke is the third most common cause of death and the main cause of acquired disability. Approximately 130,000 individuals experience a first-ever stroke per annum[1]. In addition to widely applicable pharmacological treatment for acute stroke, effective prevention and rehabilitation strategies are crucial. The development of such strategies is a major challenge for 21st-century medicine.

Exercise and physical activity have an increasing evidence base in the primary and secondary prevention of stroke and in stroke rehabilitation. The interface between physical activity and cerebrovascular disease is complex and of broad interest to clinicians, therapists, and epidemiologists. The importance of the relationship is becoming clearer: physical inactivity has been implicated by the INTERSTROKE study as one of the 5 key risk factors which account for more than 80% of the global burden of stroke[2]. Physical fitness training is increasingly being recommended as a component of stroke rehabilitation programmes due to the emerging body of evidence surrounding the benefits in improving the function after stroke[3]. The role of long-term physical activity in patients who have had a stroke in the prevention of further stroke is less clear.

Common physical impairments in Stroke[edit | edit source]

- Increased - or decreased tone

- Spasticity

- Decreased or absent sensation

- Decreased proprioception

- Decreased balance (static and/ or dynamic)

- Decreased muscle strength

- Decreased cardiorespiratory fitness/ endurance

- Decreased motor control[4]

Specific post-stroke exercise goals[edit | edit source]

Immediately after an Acute Stroke[edit | edit source]

Following the assessment of the main physical impairments present in physical activities, the physiotherapist should start addressing those impairments immediately.

Functional activities such as bed mobility, transfers, low-level walking, self-care activities, intermittent sitting or standing and seated activities can be started as soon as the initial assessment is completed (as soon as day-1). Other impairments can be addressed if indicated such as; tone normalisation techniques, range of motion exercises, balance retraining, muscle strengthening, motor control exercises, as well as sensory - and proprioceptive retraining.

At intensities that are ~ 10-20 beats/min increases in resting heart rate; rating of perceived exertion ≤11 (6-20 scale); frequency and duration as tolerated, using an interval or work: rest approach. Such activities are aimed at preventing deconditioning, hypostatic pneumonia, orthostatic intolerance, depression, and stimulating balance and coordination.

The normalizing tone/ spasticity may include;

- Passive sustained stretches

- Deep pressure

- Joint compressions

- Hydrotherapy

- Cryotherapy

- Heat-therapy

- Strengthening exerices[4]

In the past, physiotherapists often avoided including high-intensity exercise as part of stroke rehabilitation, believing that it was detrimental to the performance of motor tasks; there is now a body of evidence which clearly shows this belief to be completely unfounded.

A number of studies have shown that high-intensity exercise has no detrimental effect on spasticity[5][6]. A study[7] in which a small group of long term (more than 9 months) ambulant stroke patients concluded: "The 10-week combined program of muscle strengthening and physical conditioning resulted in gains in all measures of impairment and disability. These gains were not associated with measurable changes of spasticity in either quadriceps or ankle plantarflexors."

A 2004 review[8] of RCTs shows strong evidence for using high-intensity strengthening exercises of the lower paretic limb following stroke.

In and Outpatient Exercise Therapy or “Rehabilitation”[edit | edit source]

Cardiorespiratory fitness[edit | edit source]

Aerobic exercises that include large-muscle activities (e.g., walking, graded walking, stationary cycle ergometry, arm ergometry, arm-leg ergometry, functional activities seated exercises) if appropriate. At intensities that are ~40-70% oxygen uptake reserve or heart rate reserve; 55-80% heart rate max; rating of perceived exertion 11-14 (6-20 scale), for 3-5 days/week, 20-60 min/session (or multiple 10-min sessions), that includes a 5-10 min of warm-up and cool-down activities. Such activities are aimed at increasing walking speed and efficiency, improving exercise tolerance (functional capacity), increasing independence in activities of daily living, reducing motor impairment and improving cognition, and improving vascular health and inducing other cardio-protective benefits.

A randomized controlled trial suggests that High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) enhances peak oxygen uptake in post-stroke patients[9].

Muscle strengthening[edit | edit source]

Muscular Strength/Endurance activities include resistance training of upper and lower extremities, trunk using free weights, weight-bearing or partial weight-bearing activities, elastic bands, spring coils, pulleys, circuit training, and functional mobility. At intensities that correspond to 1 to 3 sets of 10-15 repetitions of 8-10 exercises involving the major muscle groups at 50-80% of 1 repetition max, for 2-3 days/week, with gradually increasing resistance over time as tolerance permits. Such activities are aimed at increasing muscle strength and endurance, increasing ability to perform leisure-time and occupational activities and activities of daily living, and reducing cardiac demands during lifting or carrying objects by increasing muscular strength.

According to the study published in Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation (March 2020), improvement in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was positively related to the increase in upper limb strength in stroke patients post-discharge suggesting the importance of focus on upper limb strength recovery in the outpatient rehabilitation phase (i.e., first three months after stroke)[10].

Normalising tone and Range of motion[edit | edit source]

Flexibility should also be a focus that involves static stretching of the trunk and upper- and lower extremities. Holding each stretch for 10-30 seconds, with the stretches performed 2-3 days/week (before or after aerobic or strength training). These activities increase range of motion of involved segments, help to prevent contractures, decrease risk of injury, and increase activities of daily living. A multi-centre randomized controlled trial proposed that intensive training of sit-to-stand activity improved the sit-to-stand ability in stroke patients who were not able to stand up by themselves.[11]

Motor control exercises[edit | edit source]

Neuromuscular activities such as balance and coordination activities, Tai Chi, Yoga, recreational activities (paddles/sport balls to challenge hand-eye coordination), and active-play video gaming and interactive computer games. Employ 2-3 days/week as a complement to aerobic, muscular strength/endurance training, and stretching activities. These activities improve balance, skill reacquisition, quality of life, and mobility; decrease fear of falling; and improve level of safety during activities of daily living.

The study suggests a low-frequency group exercise can facilitate exercise practice following rehabilitation among stroke survivors. This experimental study on the forty-one stroke survivors, mean age 59.34 (10.02) years, post-stroke time 17.13 (17.58) months, who attended group physiotherapy sessions (90 mins, once a week) for 12 weeks supervised by therapists suggested positive outcome with stroke survivors[12].

Make it fun![edit | edit source]

Mr. John Woloski endured a complex CVA and was referred to Allied Services Heinz Rehabilitation Hospital's Brain Injury Rehabilitation Unit. Maybe it was his love of music after decades of teaching music education in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, then Principal of Solomon/Plains Junior High School? Maybe it was his positive outlook and commitment to physical rehabilitation? Rehabilitation can and should have an element of fun.

[13]Resources[edit | edit source]

This set of presentation slides from the American Heart Association provides evidence based recommendations for exercise throughout each stage of the rehabilitation process Post Stroke:

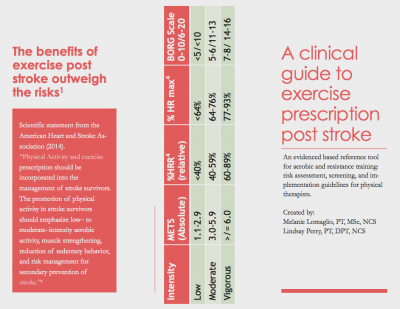

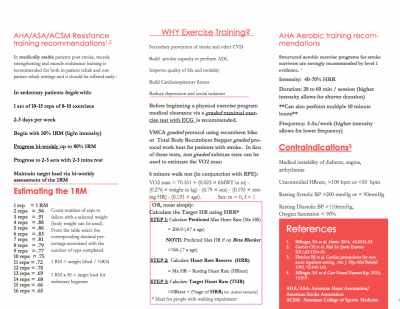

Clinical Guide to Exercise Presecription Post Stroke from the American Physical Therapy Association.

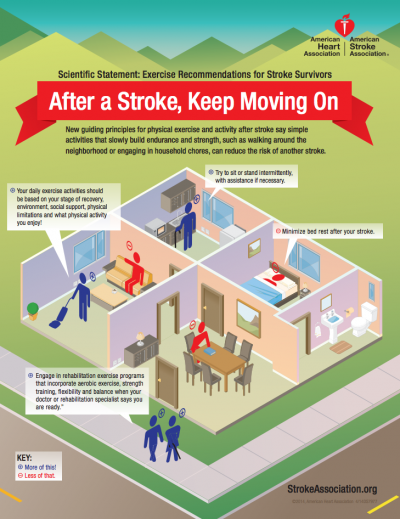

These two infographics could be used to promote exercise following stroke to your clients and provide guidance to healthcare professionals on exercise prescription:

| AHA/ASA. Physical Activity after Stroke Infographic | CDC. Increasing Physical Activity among Adults with Disabilities |

Discussion[edit | edit source]

It is estimated that 610 000 first strokes occur in the United States each year. Worldwide, it is estimated that there were 11.6 million incident ischemic strokes and 5.3 million incident hemorrhagic strokes in 2010. Although transient ischemic attacks can precede stroke, most strokes occur without warning. Stroke is a preventable disease, and control of modifiable risk factors plays the major role in prevention strategies. There is substantial, consistent evidence from numerous, high quality studies that higher PA levels are associated with significantly lower risk of stroke, and this evidence suggests that PA has a protective benefit in stroke prevention beyond the traditional stroke risk factors. With the high prevalence of physical inactivity in the general population, increasing PA levels could have a significant effect on reducing stroke incidence.

The Copenhagen Stroke Study reported that 22% of stroke survivors are unable to walk at the end of rehabilitation programmes . Independent gait is closely related to independence and achievement of activities of daily living and, therefore, is one of the aims of physical training after stroke. A systematic review investigating the effectiveness of lower-limb strengthening, cardiorespiratory or gait-oriented tasks in improving gait, gait-related activities, and health-related quality of life in stroke survivors evaluated 21 randomised controlled trials. The evidence generated supports the conclusion that gait-oriented training improves walking competency after stroke but has no significant effect on activities of daily living or health-related quality of life . A previously mentioned review examined the effects of cardiorespiratory with strength training, high-intensity physiotherapy, and repetitive task training on gait and found that only cardiorespiratory training is supported by strong evidence of beneficial effects on walking ability.

Given the numerous health benefits of PA, there are many public health guidelines on the recommended volume and intensity of PA for optimal health. Although separate guidelines for stroke prevention do not exist, the recommendations for primary stroke prevention are consistent with the current US guidelines: at least 40 minutes/d of moderate to vigorous intensity aerobic PA 3 to 4 days/wk. These recommendations should be stressed as part of an overall stroke prevention strategy, but even more so in persons with other risk factors. The literature suggests that men achieve a greater reduction in stroke risk when they engage in PA at a moderate to vigorous intensity, whereas women benefit from greater amounts of low intensity PA, such as walking. Further research is needed to clarify the type and intensity of PA, potential differences by race/ethnic groups, and use of more objective measurement of PA to clarify the dose–response relationship in men and women. The recommended PA level for stroke prevention is associated with a low risk within the general population, with an acceptable risk:benefit ratio. So to use the common motivational phraseology, just do it. And do it every day!

Summary[edit | edit source]

Low physical activity is associated with reduced mobility, walking ability (6 minute walk test), aerobic fitness (VO2 peak), reduced balance, and depression but not with age or other demographic variables. Establishing direction of causality in these associations is impossible with the available cross-sectional data; stroke impairments may directly lead to reduced activity levels, and reduced activity may lead to further reductions in fitness levels and thus mobility .Similarly, low mood could be both cause and consequence of low physical activity, and depression/low mood could negatively affect self-efficacy, motivation, and self-determination which determine the uptake and maintenance of physical activity after stroke.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), [http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/108/ Management of Patients with Stroke or TIA: assessment, Investigation, Immediate Management and Secondary Preventio. SIGN 108, A National Clinical Guideline, Edinburgh, UK, 2008.

- ↑ Gallanagh S, Quinn TJ, Alexander J, Walters MR. Physical activity in the prevention and treatment of stroke. ISRN neurology. 2011 Oct 1;2011.

- ↑ Billinger SA, Arena R, Bernhardt J, Eng JJ, Franklin BA, Johnson CM, MacKay-Lyons M, Macko RF, Mead GE, Roth EJ, Shaughnessy M. [http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/45/8/2532 Physical activity and exercise recommendations for stroke survivor. Stroke. 2014 Aug 1;45(8):2532-53.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Niam S, Cheung W, Sullivan PE, Kent S, Gu X. Balance and physical impairments after stroke. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1999 Oct 1;80(10):1227-33.

- ↑ Dawes H, Bateman A, Culpan J, Scott O, Wade DT, Roach N, Greenwood R (2003), “The effect of increasing effort on movement economy during incremental cycling exercise in individuals early after acquired brain injury.” Clin Rehabil 17(5):528-34

- ↑ Sharp SA1, Brouwer BJ. Isokinetic strength training of the hemiparetic knee: effects on function and spasticity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997 Nov;78(11):1231-6.

- ↑ Teixeira-Salmela LF, Olney SJ, Nadeau S, Brouwer B. Muscle strengthening and physical conditioning to reduce impairment and disability in chronic stroke survivors Archives of Physical Medicine October 1999, Volume 80, Issue 10, Pages 1211–1218

- ↑ R PS Van Peppen, G Kwakkel, S Wood-Dauphinee et al. The impact of physical therapy on functional outcomes after stroke: what's the evidence? Clinical Rehabilitation December 1, 2004, volume 18, issue 8, page(s): 833-862

- ↑ Gjellesvik TI, Becker F, Tjønna AE, Indredavik B, Nilsen H, Brurok B, Tørhaug T, Busuladzic M, Lydersen S, Askim T. Effects of High-Intensity Interval Training after Stroke (The HIIT-Stroke study)-A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2020 Mar 4.

- ↑ Lieshout EC, van de Port IG, Dijkhuizen RM, Visser-Meily JM. Does upper limb strength play a prominent role in health-related quality of life in stroke patients discharged from inpatient rehabilitation?. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation. 2020 Mar 11:1-9.

- ↑ de Sousa DG, Harvey LA, Dorsch S, Varettas B, Jamieson S, Murphy A, Giaccari S. Two weeks of intensive sit-to-stand training in addition to usual care improves sit-to-stand ability in people who are unable to stand up independently after stroke: a randomised trial. Journal of physiotherapy. 2019 Jun 18.

- ↑ Nordin M, Azlin N, Yusoff NA, Singh A, Kaur D. Facilitating Exercise Engagement among Community Dwelling Stroke Survivors: Is a once Per Week Group Session Sufficient?. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2019 Jan;16(23):4746.

- ↑ AlliedServicesIHSJohn Woloski and Therapists Dance for Stroke Awareness Available fromhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=3&v=Vty_PpxJG_g&feature=emb_logo