Spasticity

Original Editor - Timothy Assi

Top Contributors - Naomi O'Reilly, Sheik Abdul Khadir, Matt Ross, Rhiannon Clement, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Evan Thomas, Admin, Timothy Assi, Scott Buxton, Vidya Acharya, Garima Gedamkar, Lauren Heydenrych, Tony Lowe, Shreya Pavaskar, Wendy Walker, Ewa Jaraczewska, Oyemi Sillo, George Prudden, WikiSysop, Rachael Lowe and Rania Nasr

Definition[edit | edit source]

The most well-known and referenced description of spasticity is the physiological definition proposed by Lance in 1980. [1]More recently, a definition from Pandyan et al (2005) [2] states that spasticity is:'Spasticity is a motor disorder characterised by a velocity-dependent increase in tonic stretch reflexes (muscle tone) with exaggerated tendon jerks, resulting from hyperexcitability of the stretch reflex, as one component of the upper motor neurone syndrome.'

Spasticity is a velocity-dependent disorder of the stretch reflex that results in increased muscle tone. [3]'Disordered sensorimotor control, resulting, resulting from an upper motor neuron lesion (UMN), presenting as an intermittent or sustained involuntary activations of muscles'

Anatomy and Pathology[edit | edit source]

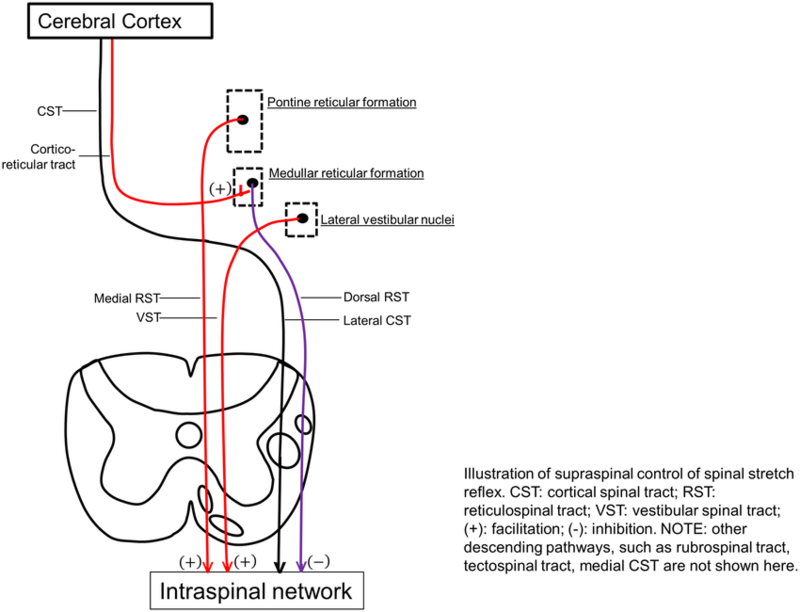

Primary impairments from an upper motor neuron lesion (UMNL) are usually due to the disruption of supraspinal control of descending pathways that control excitatory and inhibitory influences on proprioceptive, cutaneous and nociceptive spinal reflexes.

The Inhibitory System[edit | edit source]

The Excitatory System[edit | edit source]

The bulbopontine tegmentum gives rise to the Medial Reticulospinal Tract and, acting weakly with the Vestibulospinal Tract, is excitatory to both stretch and extensor reflexes and like the Dorsal Reticulospinal Tract, is also inhibitory to the flexor reflexes.

Different Lesions and Their Presentations[edit | edit source]

The signs and symptoms between Cortical UMN Lesions and Spinal Cord UMN Lesions vary due to the location of where the disruption has taken place. [4]

Normal[edit | edit source]

Both the inhibitory system (Corticospinal Tract and Dorsoreticulospinal Tract) and excitatory systems (Medial Reticulospinal and Vestibulospinal Tract) are in dynamic balance and therefore the inhibition to the spinal cord is easily adjusted according to demand.

Corticospinal Tract Lesion[edit | edit source]

Although the Corticospinal Tract has an inhibitory influence on stretch and flexor reflex, the main inhibitory system produced by the Dorsal Reticulospinal Tract remains intact and therefore the balance of excitatory and inhibitory influences are maintained.

Internal Capsule Lesion[edit | edit source]

Leads to interruption of both the Corticospinal Tract and Corticoreticular Tract pathways that are responsible for the inhibitory response and some loss of inhibition to stretch and flexor stretches. The excitatory systems from both the Medial Reticulospinal and Vestibulospinal Tract are more dominant which leads to the facilitation of extensor and stretch reflexes but inhibition of flexors.

Incomplete Spinal Cord Lesion[edit | edit source]

Signs and symptoms will vary dependant on site and extent. If the inhibitory system is affected then there will be an unopposed excitatory drive to stretch and extensor reflexes with partial inhibition of flexor reflexes.

Complete Spinal Cord Lesion[edit | edit source]

Spinal reflexes are unopposed due to the complete loss of supraspinal control. Both flexor and extensor reflexes are disinhibited and therefore people may experience both flexor and extensor spasms.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Spasticity is usually accompanied by one of more components of an upper motor neurone lesion seen in the table below, and is seldom exists in isolation. The impact of spasticity varies from person to person, ranging from being a clinical sign with no impact on function or a large increase in tone that affects transfers, mobility and personal care. It can also lead to contracture due to the shortening of muscles and tendons. [6][7]

| Positive Component | Negative Component |

|---|---|

| Exaggerated Tendon Reflexes | Spastic Co-Contractions |

| Released Reflexes | Motor Weakness |

| Babinski Sign | Slowed Movements |

| Increased Tone | Loss of Dexterity |

| Clonus | Loss of Selective Motor Control |

| Spastic Dystonia |

Permanent loss of joint range has been known to occur 3-6 weeks after both stroke and brain injury and therefore it is important that spasticity is identified early on in the assessment in order for it to be monitored and managed as required. In a person with hemiplegia the lower limb pattern is plantar flexion and inversion of the ankle with hamstring tightness limiting knee range of motion as well as adductor spasticity. Upper limb presentation is usually shoulder adduction, internal rotation, elbow flexion, forearm pronation with wrist and elbow flexion. [6][7]

Characteristics[edit | edit source]

Spasticity has a number of characteristics that differentiates it from rigidity:- Velocity dependence

- Clasp Knife Phenomenon: Limb initially resists movement and then suddenly gives way

- Distribution: Antigravity muscles being more affected

- Stroking Effect: Stroking the surface of the antagonist muscle may reduce tone in spasticity.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Ashworth Scale[edit | edit source]

The Ashworth scale is the most widely used assessment tool to measure resistance to limb movement in a clinic setting, although it is unable to distinguish between the neural and non-neural components of increased tone.[8]

The scale is as follows:

0 No increase in muscle tone

1 Slight increase in tone giving a catch when the limb is moved

2 More marked increase in tone but limb easily moved

3 Considerable increase in tone - passive movement difficult

4 Limb is rigid in flexion or extensionTardieu Scale[edit | edit source]

This scale quantifies muscle spasticity by assessing the response of the muscle to stretch applied at specified velocities. Grading is always performed at the same time of day, in a constant position of the body for a given limb. For each muscle group, reaction to stretch is rated at a specified stretch velocity. [9]

Velocity to Stretch

V1 As slow as possible

V2 Speed of the limb segment falling

V3 As fast as possible (> Natural Drop)

Quality of Muscle Reaction

0 No resistance throughout passive movement

1 Slight resistance throughout,with no clear catch at a precise angle.

2 Clear catch at a precise angle followed by release

3 Fatiguable Clonus (< 10 secs) occurring at a precise angle

4 Unfatiguable Clonus (> 10 secs) occurring at a precise angle

5 Joint Immobile

Spasticity Angle

R1 Angle of catch seen at Velocity V2 or V3

R2 Full range of motion achieved when muscle is at rest and tested at V1 velocity

Interpretation

A large difference between R1 & R2 values in the outer to middle range of normal m. length indicates a large dynamic component. [10]

A small difference in the R1 & R2 measurement in the middle to inner range indicates predominantly fixed contracture. [10]Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Since the severity of Spasticity may vary from one neurological condition to another and even from one patient to other with the same condition, disease specific spasticity measurement scales are developed. For example, in the Multiple Sclerosis (MS) population (The Multiple Sclerosis Society Spasticity Scale, MSSS-88). This is an 88-item, patient-based, interval level scale that not only looks at spasticity symptoms but also incorporates the person’s experience of spasticity and how spasticity affects their daily life. [11] However, in general the outcome measures include: [12]

- Goniometric Measurement

- Range of Passive Hip Abduction

- Ashworth Scale

- Adductor Tone Rating - Five-point Ordinal Rating of Tone, but is confined to the Adductors. [13]

- Spasm Frequency Scale - Ordinal Rank Scale (0 - 4) based on self-reporting of lower-limb spasm frequency in people with spinal cord related spasticity. It is scored depending on how many spasms are experienced in an average hour. [14]

- Clonus and Spasm Score (Self-Report). This is a further Ordinal Scale (0 - 3), based on self-reporting of the frequency and provocation of both spasms and clonus. [15]

- Numeric Rating Scale for Leg Stiffness.

- Walking and Falls Score - An estimate of fall frequency scored in an ordinal fashion (0 - 4), with 0 being no falls and 4 equating to more than 1 per day. If appropriate, a timed 10-metre walk is also recorded. [16]

- Overall Comfort Rating.

Management[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Progressive Resistance Strength Training - No evidence shows that strength training increases spasticity in patients with stroke. Musculoskeletal impairment are significantly reduced after resistance strength training. [17]

Biofeedback combined with functional electrical stimulation and occupational therapy does not increase the degree of spasticity after treatment. It also showed a greater reduction in spasticity compared to patients who performed functional electrical stimulation and occupational therapy alone. [18]

Shock wave therapy on flexor hypertonic muscles of the forearm and interosseus muscles of the hand in patients with stroke showed significant reduction of muscle tone (>3months). [19]

Amelio reported significant reduction of muscle tone (>12 weeks) of plantar flexors in children with cerebral palsy. [20]

Significant reduction of ankle plantar flexor spasticity in patients with stroke after fifteen 10-minute sessions of continuous ultrasound therapy over a 5-week period (frequency 1MHz and intensity 1,5 W/cm2). [21][22]

Cryotherapy, using cold packs (12°C) for 20-minutes, can lower the muscle temperature to reduce the spasticity. [23]

Electric Stimulation using agonist stimulation showed a significant improvement in Ashworth Scores, while antagonist stimulation showed an increase of stretch reflex-initiating angle. [24]

Pharmacological[edit | edit source]

If the spasticity is widespread then systemic medication is used. This includes:

- Dantrolene (Dantrium)

- Baclofen (Lioresal and others)

- Tizanidine (Zanaflex)

- Diazepam (Vallium)

If the spasticity is locallised then local medication is used. This includes:

- Boutulinum Toxin (Botox)

- Baclofen (Inrathecally - High concentration more locally).

- Phenol / Nerve Block

- Baclofen: The most common systemic agent. Baclofen acts on the receptors of excitatory nerve terminals, in particular the 'GABA B G-Protein receptor. Once the baclofen has attached to this G-Protein on the pre-synaptic terminal, potassium channels open while calcium channels close, hyperpolarising the cell. The inability for calcium to enter the cell means the release of glutamate, an excitatory neurotransmitter, is prohibited.

- Tizanidine: Follows the same mechanism as Baclofen, however attaches to the a2 adrenoreceptor on the pre-synaptic cell membrane.

- Botulinum Toxin (Botox): Injected locally into muscle. Prevents the excytotic release of acetylcholine at the level of the neuromuscular junction which further prevents release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum which leads to excitation-contraction coupling.

- Diazepam (Vallium): Less common. Increases the effect of GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter, that is released from inhibitory interneurons which decreases the excitability within the post-synaptic nerve terminal.

- Dantrolene: Provided orally. Blocks the release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum within the muscle which prevents excitation-contraction coupling.

Other Considerations[edit | edit source]

It is important to identify and address potential triggers and aggravating factors that can cause an exaccerbation in spasticity [6]. These may include:

- Pressure Ulcers

- Ingrown Toenails

- Skin Infections

- Injuries

- Constipation

- UTI

- DVT

- Improper Seating

- Ill Fitting Orthotics

Clinical Guidelines[edit | edit source]

The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) latest clinical guidelines in 2016 recommend the following for the management of spasticity: [25]

- People with motor weakness after stroke should be assessed for spasticity as a cause of pain, as a factor limiting activities or care, and as a risk factor for the development of contractures.

- People with stroke should be supported to set and monitor specific goals for interventions for spasticity using appropriate clinical measures for ease of care, pain and/or range of movement.

- People with spasticity after stroke should be monitored to determine the extent of the problem and the effect of simple measures to reduce spasticity e.g. positioning, passive movement, active movement (with monitoring of the range of movement and alteration in function) and/or pain control.

- People with persistent or progressive focal spasticity after stroke affecting one or two areas for whom a therapeutic goal can be identified (e.g. ease of care, pain) should be offered intramuscular botulinum toxin. This should be within a specialist multidisciplinary team and be accompanied by rehabilitation therapy and/or splinting or casting for up to 12 weeks after the injections. Goal attainment should be assessed 3-4 months after the injections and further treatment planned according to response.

- People with generalised or diffuse spasticity after stroke should be offered treatment with skeletal muscle relaxants (e.g. baclofen, tizanidine) and monitored for adverse effects, in particular sedation and increased weakness. Combinations of antispasticity drugs should only be initiated by healthcare professionals with specific expertise in managing spasticity.

- People with stroke should only receive intrathecal baclofen, intraneural phenol or similar interventions in the context of a specialist multidisciplinary spasticity service.

- People with stroke with increased tone that is reducing passive or active movement around a joint should have the range of passive joint movement assessed. They should only be offered splinting or casting following individualised assessment and with monitoring by appropriately skilled staff.

- People with stroke should not be routinely offered splinting for the arm and hand.

Resources[edit | edit source]

RCP National Clinical Guideline For Stroke

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Lance JW. Symposium synopsis. In: Feldman RG,fckLRYoung RR, Koella WP (eds). Spasticity: Disordered Motor Control. Chicago, IL: Year Book 1980:485–94.

- ↑ Pandyan AD, Gregoric M, Barnes MP et al. Spasticity: clinical perceptions, neurological realities and meaningful measurement. Disabil Rehabil 2005;27:2–6.

- ↑ Lance JW. The control of muscle tone, reflexes, and movement: Robert Wartenberg Lecture. Neurology. 1980;30(12): 1303-13.

- ↑ Stokes, M. & Stack, E. (2012). Physical Management for Neurological Conditions. 3rd Edition. Elsevier Ltd.

- ↑ Armando Hasudungan. Introduction to Upper and Lower Motor Neuron Lesions. Available from: https://youtu.be/ClXsS7O8seg[last accessed 30/10/18]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Kheder, A. and Nair, K.P.S., 2012. Spasticity: pathophysiology, evaluation and management. Practical neurology, 12(5), pp.289-298.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Graham, L.A., 2013. Management of spasticity revisited. Age and ageing, 42(4), pp.435-441.

- ↑ Ashworth B. Preliminary trial of carisoprodal in multiple sclerosis. Practitioner 1964;192:540–2.

- ↑ Tardieu G, Rondont 0, Mensch J, Dalloz J-C, Monfraix C, Tabary J-C. Responses electromyographiques a l'etirement musculaire chez l'homme normal. Rev Neurol 1957; 97: 60-61.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Boyd R, Graham K. Objective Measurement of clinical findings in the use of Botox type A for the management of children fckLR with Cerebral Palsy. European Journal of Neurology 6(Supp 4) S23-35

- ↑ Hobart J, Riazi A, Thompson A et al. Getting the measure of spasticity in MS: The Multiple Sclerosis Society Spasticity Scale (MSSS-88). Brain 2006;129(Pt1):224–34.

- ↑ Valerie L Stevenson, Louise J Lockley and Louise Jarrett, In: Assessment of the individual with spasticity, chapter 2, SPASTICITY MANAGEMENT:A PRACTICAL MULTIDISCIPLINARY GUIDE,Pg-20-21.

- ↑ Snow BJ, Tsui JKC, Bhatt MH et al. Treatment of spasticity with botulinum toxin: a double blind study.Ann Neurol 1990;28:512–15.

- ↑ Penn RD, Savoy SM, Corcos D et al. Intrathecal baclofen for severe spinal spasticity. N Engl J Med 1989;320:1517–21.

- ↑ Smith C, Birnbaum G, Carlter JL et al. Tizanidine treatment of spasticity caused by multiple sclerosis:results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. US Tizanidine Study Group. Neurology 1994;44:S34–42.

- ↑ Wade DT, Wood VA, Heller A et al. Walking after stroke: measurement and recovery over the first three months. Scand J Rehabil Med 1987;19:25–30.

- ↑ Morris SL, Dodd KJ, Morris ME. Outcomes of progressive resistance strength training following stroke: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2004 Feb;18(1):27-39.

- ↑ Lourenção MI, Battistella LR, de Brito CM, Tsukimoto GR, Miyazaki MH. Effect of biofeedback accompanying occupational therapy and functional electrical stimulation in hemiplegic patients. Int J Rehabil Res. 2008 Mar;31(1):33-41

- ↑ Manganotti P, Amelio E. Long-term effect of shock wave therapy on upper limb hypertonia in patients affected by stroke. Stroke. 2005 Sep;36(9):1967-71. Epub 2005 Aug 18.

- ↑ Amelio E, Manganotti P.Effect of shock wave stimulation on hypertonic plantar flexor muscles in patients with cerebral palsy: a placebo-controlled study. J Rehabil Med. 2010 Apr;42(4):339-43.(B)

- ↑ Ansari NN, Adelmanesh F, Naghdi S, Tabtabaei A.The effect of physiotherapeutic ultrasound on muscle spasticity in patients with hemiplegia: a pilot study. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 2006 Jul-Aug;46(4):247-52.(B)

- ↑ Ansari NN, Naghdi S, Bagheri H, Ghassabi H. Therapeutic ultrasound in the treatment of ankle plantarflexor spasticity in a unilateral stroke population: a randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 2007 May-Jun;47(3):137-43. (B)

- ↑ Harlaar J, Ten Kate JJ, Prevo AJ, Vogelaar TW, Lankhorst GJ. The effect of cooling on muscle co-ordination in spasticity: assessment with the repetitive movement test. Disabil Rehabil. 2001 Jul 20;23(11):453-61.

- ↑ Van der Salm A, Veltink PH, Ijzerman MJ, Groothuis-Oudshoorn KC, Nene AV, Hermens HJ. Comparison of electric stimulation methods for reduction of triceps surae spasticity in spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006 Feb;87(2):222-8.

- ↑ RCP (2016). National Clinical Guidelines for Stroke. Available at: https://www.strokeaudit.org/Guideline/Full-Guideline.aspx [Accessed 19th June 2018].